Aidan of Lindisfarne

Saint Aidan of Lindisfarne | |

|---|---|

Stained glass at Holy Cross Monastery | |

| Bishop | |

| Born | Around 590 Ireland |

| Died | (651-08-31)31 August 651 Parish Churchyard, Bamburgh, Northumberland |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodoxy, Roman Catholicism, Anglicanism, Lutheranism |

| Major shrine | originally Lindisfarne Abbey, Northumberland; later disputed between Iona Abbey & Glastonbury Abbey (all destroyed). |

| Feast | 31 August (Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic Church, Anglican Communion), 9 June (Lutheran Church) |

| Attributes | Monk holding a flaming torch; stag |

| Patronage | Northumbria; Firefighters |

Aidan of Lindisfarne[1]Irish: Naomh Aodhán (died 31 August 651) was an Irish monk and missionary credited with restoring Christianity to Northumbria. He founded a monastic cathedral on the island of Lindisfarne, known as Lindisfarne Priory, served as its first bishop, and travelled ceaselessly throughout the countryside, spreading the gospel to both the Anglo-Saxon nobility and to the socially disenfranchised (including children and slaves).

He is known as the Apostle of Northumbria and is recognised as a saint by the Eastern Orthodox, the Roman Catholic Church, the Anglican Communion and others.

Contents

1 Biography

1.1 Background

1.2 Missionary efforts

2 Legacy and veneration

3 Footnotes

4 References

5 Further reading

6 External links

Biography

Bede's meticulous and detailed account of Aidan's life provides the basis for most biographical sketches (both classical and modern). One notable lacuna, which (somewhat paradoxically) reinforces the notion of Bede's reliability, is that virtually nothing is known of the monk's early life, save that he was a monk at the ancient monastery on the island of Iona from a relatively young age and that he was of Irish descent.[2] Aidan was known for his strict asceticism.[3]

Background

Saint Aidan of Lindisfarne, the Apostle of Northumbria (died 651), was the founder and first bishop of the Lindisfarne island monastery in England. He is credited with restoring Christianity to Northumbria. Aidan is the Anglicised form of the original Old Irish Aodhán, (meaning “little fiery one”). Possibly born in Connacht, Aidan was originally a monk at the monastery on the Island of Iona, founded by St Columba.[4]

In the years prior to Aidan's mission, Christianity, which had been propagated throughout Britain but not Ireland by the Roman Empire, was being largely displaced by Anglo-Saxon paganism. In the monastery of Iona (founded by Columba of the Irish Church), the religion soon found one of its principal exponents in Oswald of Northumbria, a noble youth who had been raised there as a king in exile since 616. Baptized as a Christian, the young king vowed to bring Christianity back to his people—an opportunity that presented itself in 634, when he gained the crown of Northumbria.[5]

Owing to his historical connection to Iona's monastic community, King Oswald requested that missionaries be sent from that monastery instead of the Roman-sponsored monasteries of Southern England.[3] At first, they sent him a bishop named Cormán, but he alienated many people by his harshness, and returned in failure to Iona reporting that the Northumbrians were too stubborn to be converted. Aidan criticised Cormán's methods and was soon sent as his replacement.[6] He became bishop in 635.[7]

Missionary efforts

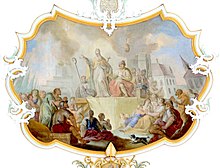

Ceiling fresco in St. Oswald Church, Bad Schussenried, Germany: King Oswald of Northumbria translates the sermon of Aidan into the Anglo-Saxon language, by Andreas Meinrad von Ow, 1778.

Allying himself with the pious king, Aidan chose the island of Lindisfarne, which was close to the royal castle at Bamburgh, as the seat of his diocese.[3] An inspired missionary, Aidan would walk from one village to another, politely conversing with the people he saw and slowly interesting them in Christianity: in this, he followed the early apostolic model of conversion, by offering "them first the milk of gentle doctrine, to bring them by degrees, while nourishing them with the Divine Word, to the true understanding and practice of the more advanced precepts."[8] By patiently talking to the people on their own level (and by taking an active interest in their lives and communities), Aidan and his monks slowly restored Christianity to the Northumbrian countryside. King Oswald, who after his years of exile had a perfect command of Irish, often had to translate for Aidan and his monks, who did not speak English at first.

In his years of evangelism, Aidan was responsible for the construction of churches, monasteries and schools throughout Northumbria. At the same time, he earned a tremendous reputation for his pious charity and dedication to the less fortunate—such as his tendency to provide room, board and education to orphans, and his use of contributions to pay for the freedom of slaves:

- He was one to traverse both town and country on foot, never on horseback, unless compelled by some urgent necessity; and wherever in his way he saw any, either rich or poor, he invited them, if infidels, to embrace the mystery of the faith or if they were believers, to strengthen them in the faith, and to stir them up by words and actions to alms and good works. … This [the reading of scriptures and psalms, and meditation upon holy truths] was the daily employment of himself and all that were with him, wheresoever they went; and if it happened, which was but seldom, that he was invited to eat with the king, he went with one or two clerks, and having taken a small repast, made haste to be gone with them, either to read or write. At that time, many religious men and women, stirred up by his example, adopted the custom of fasting on Wednesdays and Fridays, till the ninth hour, throughout the year, except during the fifty days after Easter. He never gave money to the powerful men of the world, but only meat, if he happened to entertain them; and, on the contrary, whatsoever gifts of money he received from the rich, he either distributed them, as has been said, to the use of the poor, or bestowed them in ransoming such as had been wrong fully sold for slaves. Moreover, he afterwards made many of those he had ransomed his disciples, and after having taught and instructed them, advanced them to the order of priesthood.[9]

The monastery he founded grew and helped found churches and other religious institutions throughout the area. It also served as centre of learning and a storehouse of scholarly knowledge, training many of Aidan's young charges for a career in the priesthood. Though Aidan was a member of the Irish branch of Christianity (instead of the Roman branch), his character and energy in missionary work won him the respect of Pope Honorius I and Felix of Dunwich.[10]

When Oswald died in 642, Aidan received continued support from King Oswine of Deira and the two became close friends.[11] As such, the monk's ministry continued relatively unchanged until the rise of pagan hostilities in 651. At that time, a pagan army attacked Bamburgh and attempted to set its walls ablaze. According to legend, Aidan saw the black smoke from his cell at Lindisfarne Abbey, immediately recognized its cause, and knelt in prayer for the fate of the city. Miraculously, the winds abruptly reversed their course, blowing the conflagration towards the enemy, which convinced them that the capital city was defended by potent spiritual forces.[12] Around this time, Oswine was betrayed and murdered. Two weeks later Aidan died,[13] on 31 August 651.[7] He had become ill while on one of his incessant missionary tours, and died leaning against the wall of the local church. As Baring-Gould poetically summarizes: "It was a death which became a soldier of the faith upon his own fit field of battle."[12]

Legacy and veneration

Modern statue of St. Aidan beside the ruins of the medieval priory on Lindisfarne

After his death, Aidan's body was buried at Lindisfarne, beneath the abbey that he had helped found.[14] Though his popularity waned in the coming years, "in the 11th century Glastonbury monks obtained some supposed relics of Aidan; through their influence Aidan's feast appears in the early Wessex calendars, which provide the main evidence for his cult after the age of Bede."[14]

His feast is celebrated on the anniversary of his death, 31 August. Reflecting his Irish origins, his Scottish monasticism and his ministry to the English, Aidan has been proposed as a possible patron saint for the whole of the United Kingdom.[15][16]

The Manuscript of the Martyrology of Tallaght is said to have been first composed in the Northumbrian provenance, possibly at Lindisfarne, it then passed through Iona and Bangor, where Irish scribes began to make some additions. The manuscript (now lost) finally arrived in Tallaght, where it received the majority of its Irish additions by the Óengus of Tallaght.

Today, Aidan's significance is still recognized in the following saying by Joseph Lightfoot, Bishop of Durham:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

"Augustine was the Apostle of Kent, but Aidan was the Apostle of the English."

— Bishop Lightfoot

St Aidan's College of the University of Durham was named after Aidan of Lindisfarne.

Footnotes

^ Aidan is the anglicised form of the original Old Irish Áedán.

^ See Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation (Book III) Medieval Sourcebook; David Hugh Farmer, The Oxford Dictionary of Saints. (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 8.

^ abc "St. Aidan the Bishop of Lindisfarne", Orthodox Church in America

^ St Aidan of Lindisfarne, Catholic Pure and Simple

^ Baring-Gould, 63–70.

^ Kiefer, James E., "Aidan of Lindisfarne, Missionary", Biographical Sketches of memorable Christians of the past", Society of Archbishop Justus. 29 August 1999

^ ab Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 219

^ Baring-Gould, 392.

^ As described in Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation (Book III: Chapter V); Butler, 406–407.

^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Aidan". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 435..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Christina Hole. Saints in Folklore. (London: G. Bell and Sons, 1966), 110–111; Butler, 398.

^ ab Baring-Gould, 399.

^ Chambers & Thomson

^ ab Farmer, David Hugh, 9.

^ Bradley, Ian (26 August 2002). "Wanted: a new patron saint". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

^ Cahal Milmo (23 April 2008). "Home-grown holy man: Cry God for Harry, Britain and... St Aidan". The Independent. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

References

Webb, Alfred (1878). " Aidan, Saint". A Compendium of Irish Biography. Dublin: M. H. Gill & son. Wikisource

Aidan, Saint". A Compendium of Irish Biography. Dublin: M. H. Gill & son. Wikisource

- Attwater, Donald and Catherine Rachel John. The Penguin Dictionary of Saints. 3rd edition. New York: Penguin Books, 1993.

ISBN 0-14-051312-4. - Baring-Gould, S. (Sabine). The Lives of the Saints. With introduction and additional Lives of English martyrs, Cornish, Scottish, and Welsh saints, and a full index to the entire work. Edinburgh: J. Grant, 1914.

- Butler, Alban. Lives of the Saints, Edited, revised, and supplemented by Herbert Thurston and Donald Attwater. Palm Publishers, 1956.

Farmer, David Hugh. The Oxford dictionary of saints (5th ed. Rev. ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199596607.

Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third revised ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

Further reading

Chambers, Robert & Thomson, Thomas Napier (1857). Aidan, Saint. A biographical dictionary of eminent Scotsmen. 1. Glasgow: Blackie and son. pp. 35–38.

Chambers, Robert & Thomson, Thomas Napier (1857). Aidan, Saint. A biographical dictionary of eminent Scotsmen. 1. Glasgow: Blackie and son. pp. 35–38.

- Cosmos, Spencer. "Oral Tradition and Literary Convention in Bede's Life of St. Aidan", Classical Folia 31 (1977): 47–63.

- Mayr-Harting, Henry. The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England (London: Batsford, 1972)

- Pelteret, David A.E. "Aidan d. 651." in Reader's Guide to British History (London: Routledge, 2003), historiography; online in Credo Reference

- Simpson, Ray. 'Aidan of Lindisfarne – Irish flame warms a new world'(Wipf and Stock

ISBN 9781625647627) (2014) novel and extensive historical notes.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aidan of Lindisfarne. |

Wikisource has the text of the 1885–1900 Dictionary of National Biography's article about Saint Aidan. |

Aidan 1 at Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England

- St. Aidan's Anglican, Hurstville Grove, Sydney

- St. Aidan Anglican Church, Moose Jaw, SK

- St. Aidan's Eastern-Orthodox Church, Manchester UK

Christian titles | ||

|---|---|---|

New diocese | Bishop of Lindisfarne 635–651 | Succeeded by Finan |