Provinces of Ireland

Provinces of Ireland Cúigí na hÉireann | |

Location | |

| |

Leinster Munster Connacht Ulster | |

Statistics | |

| Area: | 84,421 km² |

|---|---|

| Population (2011): | 6,241,700 |

Since the early 17th-century there have been four Provinces of Ireland: Connacht, Leinster, Munster and Ulster. The Irish word for this territorial division, cúige, meaning "fifth part", indicates that there were once five, however in the medieval period there were more. The number of provinces and their delimitation fluctuated until 1610 when they were permanently set by the English administration of James I. The provinces of Ireland no longer serve administrative or political purposes, but function as historical and cultural entities.

Contents

1 Etymology

2 History

2.1 Structure

2.2 Early medieval period

2.3 Later medieval period

2.4 Norman Ireland

2.5 Tudor period

3 Prehistory

3.1 The Three Collas and the founding of Airgíalla

4 Usage

5 Provincial flags and arms

6 Demographics and politics

7 Poetic description

8 See also

9 References

9.1 Citations

9.2 Sources

Etymology

In modern Irish the word for province is cúige (pl. cúigeadh). The modern Irish term derives from the Old Irish cóiced (pl. cóiceda) which literally meant "a fifth".[1] This term appears in 8th century law texts such as Miadslechta and in the legendary tales of the Ulster Cycle where it refers to the five kingdoms of the "Pentarchy".[1] In the 12th-century Lebor na Cert (Book of Rights), the term means province, seemingly having lost its fractional meaning with seven cúigeadh listed.[1] Similarly this seems to be the case in regards to titles with the Annals of Ulster using the term rex in Chóicid (king of the fifth/province) for certain overkings.[1]

History

Early medieval cóiceda (over-kingdoms) of Ireland, c.800

The origins of the provinces of Ireland can be traced to the medieval cóiceda (literally "fifths") or "over-kingdoms" of Ireland. There were theoretically five such over-kingdoms, however in reality during the historical period there were always more.[2][3] At the start of the 9th-century the following are listed: Airgíalla, Connachta, Laigin, Northern Uí Néill (Ailech), Southern Uí Néill (Mide), Mumu, and Ulaid.[2][3] These seven over-kingdoms are again listed in the 12th-century Lebor na Cert.[1]

Structure

Each over-kingdom was divided into smaller territorial units, the definition of which, whilst not consistent in Irish law tracts, followed a pattern of different grades.[2] In theory in the early medieval period:

- A province was ruled by a "king of over-kings", known as a rí ruírech. This was the highest rank allowed for in Irish law tracts despite claims by some dynasties to the symbolic title of rí Temro (king of Tara), also known as the ard rí (High King of Ireland);[1][2] The term rí ruírech was replaced at a later date by the term rí cóicid, "king of a fifth".[1]

- Each province was made up of several petty-kingdoms that corresponded roughly to the size of modern Irish counties or dioceses, and were ruled by an overking known as a ruirí;[2]

- Each of these petty-kingdoms were further subdivided into smaller petty-kingdoms known as a túath (a group of people), equating at their largest to the size of an Irish barony.[2] These túath were ruled by a king, or rí, and were also known as a rí túaithe, or "king of the people".[2] By the 10th-century the rulers of a túath were no longer assumed to be kings but became referred to as tigern (a lord) or toísech (a leader) instead.[2]

This pyramid structure however by the later medieval period had little validity.[2]

Paul MacCotter proposes the following structure of lordship in the 12th-century: High-king of Ireland; semi-provincial king, such as Connacht, Ulaid, Desmumu; regional king, such as Dál Fiatach and Uí Fhiachrach Aidni; local king or king of a trícha cét, such as Leth Cathail or Cenél Guaire; and taísig túaithe at the bottom.[4]

Early medieval period

Map of Ireland's over-kingdoms circa 900 AD.

The kingdom of Osraige, which had its genealogy traced back by early Irish genealogists to the Laigin, was part of Mumu from the 6th to 8th century and ruled by the Corcu Loígde dynasty.[5] By the 7th-century Osraige had lost their dependence on the Corcu Loígde,[5] with the restoration of the local Dál Birn dynasty. Osraige remained part of Mumu until 859 when Máel Sechnaill I, king of the Uí Néill, forced Mumu to surrender it to his overlordship.[5][6] After this situation ended it became an independent kingdom which gradually moved towards the Laigin sphere of influence as they sought to claim the Laigin kingship.[5] It was during the 9th-century that Osraige, ruled by Cerball mac Dúnlainge, became a major political player.[7]

Airgíalla had come under the dominance of the Ulaid,[8] however Niall Caille, the son of Áed Oirdnide, brought it under the hegemony of the Northern Uí Néill after defeating the combined forces of the Airgíalla and Ulaid at the battle of Leth Cam in 827.[9][10][11][12]

Later medieval period

After a period of dynastic infighting in the early 12th-century, Osraige fragmented and after a heavy defeat at the hands of High-King Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn became part of Laigin. In 1169, the king of Osraige, Domnall Mac Gilla Pátraic, hired the Norman knight Maurice de Prendergast to resist the Laigin king, Diarmait Mac Murchada, who had also recruited Norman aid.[13]

In 1118, the king of Connacht, Tairrdelbach Ua Conchobair, aided the Mac Cárthaigh of south Munster in a rebellion against the ruling Uí Briain dynasty.[14] This resulted in the division of Mumu into two: Tuadmumu (Thomond, meaning "north Munster") to the north under the Uí Briain; and Desmumu (Desmond, meaning "south Munster") to the south under the Mac Cárthaigh.[14] Ua Conchobair would then conquer the heartland of the Uí Briain situated around modern County Clare and make it part of Connacht.[14] This was to force them to accept Cormac Mac Carthaig, king of Desmumu, as the king of Mumu.[14] Despite Ua Conchobair's aid, Mac Carthaig and the Uí Briain would form an alliance to campaign against Connacht's hegemony, and by 1138 ended the threat from that kingdom.[14] The following decades would see Mumu united and repartitioned several times as the Uí Briain and Mac Cárthaigh vied for complete control.[14] In 1168, the king of Connacht, Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair, ensured Mumu remained divided.[14] After Henry II, king of England, landed in Ireland in 1171, the Mac Cárthaigh submitted to him to prevent an Uí Briain invasion.[14] The Uí Briain eventually followed suit in submitting to Henry II.[14] The eagerness of these submissions encouraged Henry II to revive the papal grant, Laudabiliter, for Ireland.[14]

Norman Ireland

Osraige would be amongst the first Irish kingdoms to fall following the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1170, and was soon afterwards split from Leinster and made part of the royal demesne lands of Waterford.[5]

In the years following the invasion, the kingdoms of Connacht, Desmumu, Laigin, Mide, Tuadmumu, and Ulaid formed the basis for the Norman liberties of Connacht, Desmond, Leinster, Meath, Thomond and Ulster respectively.[15][16] These liberties were later subdivided into smaller ones that became the basis for the counties of Ireland.[15]

The Northern Uí Néill remained outside of Norman control, eventually absorbing the greater part of Airgíalla, which had by the end of the 12th-century lost its eastern territory (afterwards known as "English Oriel" and later as Louth) to the Normans.[11] Airgíalla would eventually no longer be reckoned an over-kingdom however it survived in present-day County Monaghan for as long as the Gaelic order survived,[17] with the last king of Airgíalla being Hugh Roe McMahon, who reigned from 1589 until his execution in September/October 1590.

With the collapse of English control in Ireland following the Bruce campaign in Ireland in 1315, and the subsequent collapse of the Earldom of Ulster, the Gaelic order had a resurgence and the Clandeboye O'Neills of the Northern Uí Néill stepped into the power vacuum in Ulster bringing it under the sovereignty of the O'Neills of Tyrone. After this they claimed for the first time the title of rí Ulad, "king of Ulster", amalgamating their territory into one united province. This reduced the number of provinces to five—Connact, Leinster, Meath, Munster, and Ulster.

Tudor period

Johann Homann's 1716 map of Ireland. Note that he incorrectly places County Clare in Connacht; it had actually been returned to Munster in the immediate years after 1660.

During the reign of Mary I (1553-1558), the Lord Deputy of Ireland, Thomas Radclyffe, 3rd Earl of Sussex, sought to divide Ireland into six parts—Connaught, Leinster, Meath, Nether Munster, Ulster, and Upper Munster.[15] His administrative reign in Ireland however was cut short and even with his reappointment by Elizabeth I (1568-1603) this plan was never implemented.[15]

Sir Henry Sidney during his three tenures as Lord Deputy created two presidencies headed by a Lord President to administer Connaught and Munster.[15] In an attempt to reduce the importance of the province of Munster, Sydney, using the River Shannon as a natural boundary took Thomond and made it into the county of Clare as part of the presidency of Connaught in 1569.[15] Around 1600 near the end of Elizabeth's reign, Clare was made an entirely distinct presidency of its own under the Earls of Thomond and would not return to being part of Munster until after the Restoration in 1660.[15]

The exact boundaries of the provinces of Ireland during the Tudor period changed several times, usually as a result of the creation of new counties:

- County Clare upon its creation in 1569 was transferred from Munster to Connacht, and was only restored to Munster after 1660.[15]

County Longford upon its creation in 1583 was transferred from Leinster to Connacht.[15][18]

County Cavan was created in 1584 and transferred from Connacht to Ulster.[19]

County Louth, which had long being part of The Pale, was transferred from Ulster to Leinster.[15]

It would not be until the reign of Elizabeth's successor, James I, that Meath by 1610 would cease to be considered a province and that the provincial borders would be permanently set.[15]

Prehistory

The earliest recorded mention of the major division of Ireland is in the Ulster Cycle of legends, such as the Táin Bó Cúailnge.[20][21] The Táin is set during the reign of Conchobar Mac Nessa, king of Ulster, and is believed to have happened in the 1st century.[22] In this period Ireland is said to have been divided into five independent over-kingdoms, or cuigeadh whose rí (kings) were of equal rank, not subject to a central monarchy.[20][1][22][23] Pseudo-historians called this era Aimser na Coicedach, which has been translated as: "Time of the Pentarchs";[20] "Time of the Five Fifths";[22] and "Time of the provincial kings".[23] It was also described as "the Pentarchy".[20][21]

The five provinces that made up the Pentarchy where:[20][21][22]

Connacht, with its royal seat at Cruachain.

Ulaid (Ulster), with its royal seat at Emain Macha.

Muman (Munster), with its royal seat at Teamhair Erann.

Laigen Tuathgabair (North Leinster), with its royal seat at Tara (before it became the seat of the High King).

Laigen Desgabair (South Leinster), with its royal seat at Dinn Riogh.

Historians Geoffrey Keating and T. F. O'Rahilly differ suggesting that it is Munster, not Leinster, that formed two of the fifths.[23][24] These two fifths were called by Keating: Cuigeadh Eochaidh (eastern Munster) and Cuigeadh Con Raoi (western Munster),[24] both named after their respective king. Eoin MacNeill discounts this suggestion citing the Táin Bó Cúailnge, which makes mention of Eochaidh as king of all Munster, with Cu Roi simply a "great Munster hero".[20] He also cites that the Táin makes mention of the four fifths of Ireland that waged war on Ulster, which made reference to only one Munster.[20] Another reason given by MacNeill was a problem made by Keating himself. According to Keating, when the province of Míde was being founded, it was created from portions of each province which all met at the hill of Uisnech. The boundaries given by Keating himself for the five provinces however meant that this would have been highly unlikely, with the boundary between his Munster fifths nowhere near this area.[20]

Pseudo-historians list 84 kings of Ireland prior to the formation of the Pentarchy. When this mythical kingship was interrupted is a matter of dispute. The Annals of Tigernach state that Ireland was divided into the five upon the slaying of Conaire Mór, however it is suggested alternatively that it happened upon the death of Conaire's father, Eterscél Mór, the 84th king of Ireland.[23] Keating however suggests it occurred in the reign of Eochu Feidlech who was the 82nd king of Ireland.[23]

MacNeill claims that this division of Ireland into five is pre-historic and pre-Gaelic, describing the Pentarchy as "the oldest certain fact in the political history of Ireland".[20] The notion of Ireland being divided into five permeated itself throughout Irish literature over the centuries despite what the cuigeadh representing no longer existing by the time of Saint Patrick in the 5th century.[20] By then, Ireland had become divided into seven over-kingdoms.[20]

The Three Collas and the founding of Airgíalla

The main body of the events in the myth of the Three Collas may have occurred in the late 4th to early 5th century, however as the centuries passed the myth underwent updating and alteration.[25] The most oft quoted version of their story was written by Geoffrey Keating in the 17th century in his work the Foras Feasa ar Éirinn, also known as "The History of Ireland".[25]

In it the Three Collas—Colla Menn, Colla Da Crioch, and Colla Uais—were the sons of Eocaidh Doimlén.[25] It is from them that the Airgíalla are said to descend, branching off from the rest of the Connachta.[25] The Northern and Southern Uí Néill dynasties are claimed to descend from Eocaidh's brother, Fiacha Sraibhtine.[25] According to the story the Collas were told by Fiacha's son, Muiredach Tirech, the High King of Ireland, to conquer land of their own to pass on to their descendants, directing them to wage war on the Ulaid to avenge a slight against their great-grandfather Cormac mac Airt.[25]

The Collas with their army along with a host from Connacht marched to Achaidh Leithdeircc in Fernmagh, southern Ulaid, and fought the Ulaid in seven battles over the course of seven days.[25] The host from Connacht fought the first six battles, and the Collas fought the seventh.[25] It is after this last battle that the king of Ulaid, Fergus Foga, was killed and his army routed.[25] The Collas then pursued the Ulaid east of the "Glen Righe" (the valley of the Newry River in eastern County Armagh), before returning to loot and burn the Ulaid capital, Emain Macha, after which it never again had a king.[25] They then took possession of central Ulaid spanning the modern counties of Armagh, Fermanagh, Londonderry, Monaghan and Tyrone founding the over-kingdom of Airgíalla.[25]

Usage

In modern times the provinces have become associated with groups of counties, although they have no legal status. They are today seen mainly in a sporting context, as Ireland's four professional rugby teams in Pro14 play under the names of the provinces, and the Gaelic Athletic Association has separate GAA provincial councils and Provincial championships.

Six of the nine Ulster counties form modern-day Northern Ireland, which is part of the United Kingdom. Northern Ireland is a province of the United Kingdom, and is sometimes referred to by this term. These two inconsistent usages of the word "province" (along with the use of the term "Ulster" to describe Northern Ireland) can cause confusion.

Provincial flags and arms

Each Province is today represented by its own unique arms and flag, these are joined together to represent various All Ireland sports teams and organisations via the Four Provinces Flag of Ireland and a four province Crest of Ireland, examples include the Ireland national field hockey team, Ireland Curling team, Ireland national rugby league team, Ireland national rugby union team and Irish Amateur Boxing Association.

Four Provinces Flag of Ireland

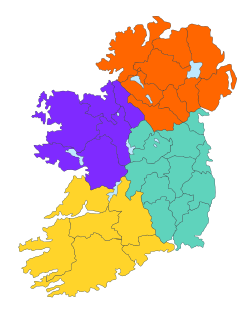

Four Provinces Location map with Emblems

Provincial Flag of Connacht

Provincial Flag of Ulster

Provincial Flag of Munster

Provincial Flag of Leinster

Provincial Flag of Mide, a former province

Demographics and politics

| Province | Flag | Irish name | Population (2016) | Area (km²) | GDP (euro) (2012) | GDP per capita (euro) (2012) | Density | Number of Counties† | Chief city |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Leinster | Laighin Cúige Laighean | 2,630,720 | 19,800 | 100 bn | 40,000 | 126.5 | 12 | Dublin | |

Ulster | Ulaidh Cúige Uladh | 2,158,850‡ | 21,882 | 50 bn | 23,000 | 96.3 | 9 | Belfast | |

Munster | Mumhain Cúige Mumhan | 1,280,394 | 24,675 | 50 bn | 40,000 | 50.5 | 6 | Cork | |

Connacht | Connachta Cúige Chonnacht | 550,742 | 17,788 | 15 bn | 30,000 | 30.5 | 5 | Galway |

Note 1: † "Number of Counties" is traditional counties, not administrative ones.

Note 2: ‡ Population for Ulster is the sum of the 2016 census results for counties of Ulster in Republic of Ireland and the 2016 mid-year population estimates for Northern Ireland.[26] Population for other provinces is all 2016 census results.

Poetic description

This dinnseanchas poem named Ard Ruide (Ruide Headland) poetically describes the kingdoms of Ireland. Below is a translation from Old Irish:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

Connacht in the west is the kingdom of learning, the seat of the greatest and wisest druids and magicians; the men of Connacht are famed for their eloquence, their handsomeness and their ability to pronounce true judgement.

Ulster in the north is the seat of battle valour, of haughtiness, strife, boasting; the men of Ulster are the fiercest warriors of all Ireland, and the queens and goddesses of Ulster are associated with battle and death.

Leinster, the eastern kingdom, is the seat of prosperity, hospitality, the importing of rich foreign wares like silk or wine; the men of Leinster are noble in speech and their women are exceptionally beautiful.

Munster in the south is the kingdom of music and the arts, of harpers, of skilled ficheall players and of skilled horsemen. The fairs of Munster were the greatest in all Ireland.

The last kingdom, Meath, is the kingdom of Kingship, of stewardship, of bounty in government; in Meath lies the Hill of Tara, the traditional seat of the High King of Ireland. The ancient earthwork of Tara is called Rath na Ríthe ('Ringfort of the Kings').

See also

- ISO 3166-2:IE

- Counties of Ireland

- Kings of Ulster

- Kings of Munster

- Kings of Mide

- Kings of Connacht

- Kings of Leinster

- Kings of Airgíalla

- Kings of Ailech

References

Citations

^ abcdefgh Koch, pp. 459-460.

^ abcdefghi Duffy (2014), pp. 8-10.

^ ab Byrne.

^ MacCotter, p. 46.

^ abcde Duffy (2005), p. 358.

^ Duffy (2014), p. 19.

^ Duffy (2005), p. 74.

^ Duffy (2014), p. 21.

^ Bardon, p. 14.

^ Duffy (2005), pp. 490-1.

^ ab Duffy (2014), p. 24.

^ Duffy (2005), p. 12.

^ Duffy (2005), p. 32.

^ abcdefghij Duffy (2005), p. 458.

^ abcdefghijk Falkiner, Caesar Litton. The Counties of Ireland: An Historical Sketch of Their Origin, Constitution, and Gradual Delimitation. Royal Irish Academy..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ MacCotter, p. 186.

^ Connolly, p. 12.

^ John G. Crawford, Anglicising the Government of Ireland: The Irish Privy Council & the Expansion of Tudor Rule 1556–1578, Blackrock, 1993

^ Desmond Roche, Local Government in Ireland, Dublin, 1982

^ abcdefghijk Eoin MacNeill (1920). The Five Fifths of Ireland.

^ abc Hogan, p. 1

^ abcd Hurbert, pp. 169-171

^ abcde Stafford & Gaskill, p. 75

^ ab John MacNeill, p. 102

^ abcdefghijk Schlegel, pp. 160-4.

^ "2016 Mid Year Population Estimates for Northern Ireland". Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. 22 June 2017. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

Sources

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Bardon, Jonathan (2005). A History of Ulster. The Blackstaff Press. ISBN 0-85640-764-X.

Byrne, Francis (2001). Irish Kings and High Kings (3 ed.). Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1851821969.

Connolly, S.J., ed. (2007). Oxford Companion to Irish History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923483-7.

Duffy, Seán (2014). Brian Boru and the Battle of Clontarf. Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7171-6207-9.

Duffy, Seán (2005). Medieval Ireland An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

Hubert, Henri. "The Greatness and Decline of the Celts"..

Hogan, James (1928). The Tricha Cét and Related Land-Measures. Royal Irish Academy.

Koch, John T. "Celtic Culture: Aberdeen breviary-celticism".

MacCotter, Paul (2008). Medieval Ireland: Territorial, Political and Economic Divisions. Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-84682-557-6.

MacNeill, Eoin (1920). "The Five Fifths of Ireland". Phases of Irish History. M.H. Gill & Son, Ltd..

MacNeill, John (1911). Early Irish Population-Groups: Their Nomenclature, Classification, and Chronology. Royal Irish Academy.

Schlegel, Donald M. The Origin of the Three Collas and the Fall of Emain. Clogher Record, Vol. 16, No. 2 (1998), pp. 159-181. Clogher Historical Society.

Stafford, Fiona J.; Gaskill, Howard. "From Gaelic to Romantic: Ossianic Translations".