Hanuman

| Hanuman | |

|---|---|

God of Strength, Knowledge and Bhakti; Lord of Celibacy and Victory; Supreme destroyer of evil; and protector of devotees; | |

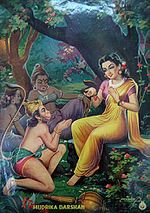

Hanuman painted in Pahari style | |

| Affiliation | Deva Devotee of Devi Sita and Lord Rama[1] Avatar of Lord Shiva |

| Abode | Earth (Prithvi) |

| Mantra | ॐ हं हनुमते नमः (Om Hum Hanumate Namah) |

| Weapon | Gada (mace) |

| Texts | Ramayana, Ramcharitmanas, Hanuman Chalisa, Sunderkand, Bajrang Baan, hanuman bahuk[2] |

| Personal information | |

| Born | Anjaneri, Bellary, India |

| Parents |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

Supreme deity

|

Important deities

|

Holy scriptures

|

Sampradayas

|

Philosophers–acharyas

|

Related traditions

|

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

|

Concepts

|

Schools

|

Deities

|

Texts Scriptures

Other texts

Text classification

|

Practices Worship

Arts

Rites of passage

Festivals

|

Gurus, saints, philosophers

|

Society

|

Other topics

|

|

In Hinduism, Hanuman (/ˈhʌnʊˌmɑːn/; IAST: Hanumān, Sanskrit: हनुमान्)[4] is an ardent devotee of Lord Rama.[1] Lord Hanuman Known as the Lord of Celibacy, Hanuman was a Naistika, Nithya Brahmachari, Complete Celibate, and one of the central character of Indian Epic Ramayana found in the Indian subcontinent. As one of the Chiranjivi, he is also mentioned in several other texts, such as the Mahabharata,[1] the various Puranas and some Jain,[5]Buddhist,[6] (although scholar-Buddhists find no trace of the name in the Buddhist canon) and Sikh texts.[7] Several later texts also present him as Son or RudraAmsam of Shiva (Husband of Adi Shakti).[1] Hanuman is the son of Anjana and Kesari and is also son of the wind-god Vayu, who according to several stories, played a role in his birth.[3][8]

His theological origins in Hinduism are unclear. Alternate theories include him having ancient roots, being a non-Aryan deity who was Sanskritized by the Vedic Aryans, or that he is a fusion deity who emerged in literary works from folk Yaksha protector deities and theological symbolism.[9][10]:39–40

While Hanuman is one of the central characters in the ancient Hindu epic Ramayana, the evidence of devotional worship to him is missing in the texts and archeological sites of ancient and most of the medieval period. According to Philip Lutgendorf, an American Indologist known for his studies on Hanuman, the theological significance and devotional dedication to Hanuman emerged about 1,000 years after the composition of the Ramayana, in the 2nd millennium CE, after the arrival of Islamic rule in the Indian subcontinent.[11]Bhakti movement saints such as Samarth Ramdas expressed Hanuman as a symbol of nationalism and resistance to persecution.[12] In the modern era, his iconography and temples have been increasingly common.[13] He is viewed as the ideal combination of "strength, heroic initiative and assertive excellence" and "loving, emotional devotion to his personal god Rama", as Shakti and Bhakti.[14] In later literature, he has been the patron god of martial arts such as wrestling, acrobatics, as well as meditation and diligent scholarship.[1] He symbolizes the human excellences of inner self-control, faith and service to a cause, hidden behind the first impressions of a being who looks like a Ape-Man Vanar.[13][15][9]

Besides being a popular deity in Hinduism, Hanuman is also found in Jainism and Buddhism.[5][16] He is also a legendary character in legends and arts found outside the Indian subcontinent such as in Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Malaysia and Indonesia. Outside India, Hanuman shares many characteristics with the Hindu versions in India, but differs in others. He is heroic, brave and steadfastly chaste & Fully Celibate, much like in the Sanskrit tradition. But differs in other cultures, as is the case in a few regional versions in India. Hanuman is stated by scholars to be the inspiration for the allegory-filled adventures of a monkey hero in the Xiyouji (Journey to the West) – the great Chinese poetic novel influenced by the travels of Buddhist monk Xuanzang (602–664 CE) to India.[5][17]

Contents

1 Nomenclature

2 Historical development

2.1 Vedic roots

2.2 Tamil roots

2.3 Epics and Puranas

2.4 Late medieval and modern era

3 Birth

4 Childhood

5 Adulthood

6 Attributes

7 Texts

7.1 Hinduism

7.1.1 Ramayana

7.1.2 Mahabharata

7.1.3 Other literature

7.1.4 Hanuman Chalisa

7.2 Buddhism

7.3 Jainism

7.4 Sikhism

7.5 Southeast Asian texts

8 Significance and influence

9 Iconography

10 Temples and shrines

10.1 Festivals and celebrations

11 Hanuman in Southeast Asia

11.1 Cambodia

11.2 Indonesia

11.3 Thailand

12 In non-religious pop culture

13 See also

14 References

14.1 Bibliography

15 Further reading

16 External links

Nomenclature

Hanuman with a Namaste (Anjali Hasta) posture

The meaning or the origin of word "Hanuman" is unclear. In the Hindu pantheon, deities typically have many synonymous names, each based on the noble characteristic or attribute or reminder of that deity's mythical deed.[10]:31–32 Hanuman has many names like Maruti, Pawansuta, Bajrangbali, Mangalmurti but these names are rarely used. Hanuman is the common name of the vaanar (semi-ape, semi-man) god.

One interpretation of the term is that it means "one having a jaw (hanu) that is prominent (mant)". This version is supported by a Puranic legend wherein baby Hanuman mistakes the sun for a fruit, attempts to heroically reach it, is wounded and gets a disfigured jaw.[10]:31–32

A second, less common interpretation is that the name derives from the Sanskrit words Han ("killed" or "destroyed") and maana (pride); the name implies "one whose pride was destroyed". This epithet resonates with the story in the Ramayana about his emotional devotion to Rama and Sita. He combines two of the most cherished traits in the Hindu bhakti-shakti worship traditions: "heroic, strong, assertive excellence" and "loving, emotional devotion to personal god".[10]:31–32

A third conjecture is found in Jain texts. This version states that Hanuman spent his childhood on an island called Hanuruha, which served as the origin of his name.[10]:189

Linguistic variations of "Hanuman" include Hanumat, Anuman (Tamil), Hanumantha (Kannada), Hanumanthudu (Telugu). Other names of Hanuman include:

Anjaneya,[18]Anjaniputra (Kannada), Anjaneyar (Tamil), Anjaneyudu (Telugu), Anjanisuta all meaning "the son of Hanuman's mother Anjana".

Kesari Nandan, based on his father, which means "son of Kesari"

Maruti, or the son of the wind god;[19]

Bajrang Bali, "the strong one (bali), who had limbs (anga) as hard as a vajra (bajra)"; this name is widely used in rural North India.[10]:31–32

Sang Kera Pemuja Dewa Rama, Hanuman, the Indonesian for "The mighty devotee of Rama, Hanuman"

Sankata Mochana, the remover of dangers (sankata)[10]:31–32

Outside the Indian subcontinent, though his iconography and the details of his legends vary, his names are phonetic similar to the Indian version:

- Andaman, this name and Hanuman's mythology is behind the Indian islands in the Bay of Bengal called Andaman and Nicobar.[20]

- Anoman (Javanese, Indonesia)[21]

- Hanuman (Malaysia)[22]

- Hanuman in Myanmar,[23] Cambodia,[24] Thailand, and Balinese Indonesia.[25][26]

- Hunlaman (Lao)[citation needed]

Historical development

Standing Hanuman, Chola Dynasty, 11th century, Tamil Nadu, India

Vedic roots

The earliest mention of a divine monkey, interpreted by some scholars as the proto-Hanuman, is in hymn 10.86 of the Rigveda, dated to between 1500 and 1200 BCE. The twenty-three verses of the hymn are a metaphorical and riddle-filled legend. It is presented as a dialogue between multiple characters: the god Indra, his wife Indrani and an energetic monkey it refers to as Vrisakapi and his wife Kapi.[27][28][10]:39–40 The hymn opens with Indrani complaining to Indra that some of the soma offerings for Indra have been allocated to the energetic and strong monkey, and the people are forgetting Indra. The king of the gods Indra responds by telling his wife that the living being (monkey) that bothers her is to be seen as a friend, and that they should make an effort to coexist peacefully. The hymn closes with all agreeing that they should come together in Indra's house and share the wealth of the offerings.[10]:39–40

This hymn, which includes an explicit discussion of sex and differences between species, has been interpreted in a number of ways by contemporary scholars.[28][10]:305 R.N. Dandekar states that it may metaphorically refer to another fertility god, while Wendy Doniger compares it to a horse sacrifice. Stephanie Jamison states that the hymn mentions a bull-monkey, a euphemism for a horse and fertility ritual, very different from the later era Hanuman. According to Philip Lutgendorf, there is "no convincing evidence for a monkey-worshipping cult in ancient India".[28]

Tamil roots

The orientalist F. E. Pargiter (1852-1927) theorized that Hanuman was a proto-Dravidian deity.[10]:40 According to this theory, the name "Hanuman" derives from the Tamil word for male monkey (ana-mandi), first transformed to "Anumant" – a name which remains in use. "Anumant", according to this hypothesis, was later Sanskritized to "Hanuman" because the ancient Aryans confronted with a popular monkey deity of ancient Dravidians coopted the concept and then Sanskritized it.[10]:39–40[29] According to Murray Emeneau, known for his Tamil linguistic studies, this theory does not make sense because the Old Tamil word mandi in Caṅkam literature can only mean "female monkey", and Hanuman is male. Further, adds Emeneau, the compound ana-mandi makes no semantic sense in Tamil, which has well developed and sophisticated grammar and semantic rules. The "prominent jaw" etymology, according to Emeneau, is therefore plausible.[10]:39–40

Epics and Puranas

.mw-parser-output .quotebox{background-color:#F9F9F9;border:1px solid #aaa;box-sizing:border-box;padding:10px;font-size:88%}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft{margin:0.5em 1.4em 0.8em 0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright{margin:0.5em 0 0.8em 1.4em}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.centered{margin:0.5em auto 0.8em auto}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft p,.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright p{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-title{background-color:#F9F9F9;text-align:center;font-size:larger;font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:before{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" “ ";vertical-align:-45%;line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:after{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" ” ";line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .left-aligned{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .right-aligned{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .center-aligned{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .quotebox cite{display:block;font-style:normal}@media screen and (max-width:360px){.mw-parser-output .quotebox{min-width:100%;margin:0 0 0.8em!important;float:none!important}}

Sita's scepticism

Vanaranam naranam ca

kathamasit samagamah

Translation:

How can there be a

relationship between men and monkeys?

—Valmiki's Ramayana'

Sita's first meeting with Hanuman

(Translator: Philip Lutgendorf)[30]

Hanuman is mentioned in both the Hindu epics, Ramayana and Mahabharata.[31] A twentieth-century Jesuit missionary Camille Bulcke, in his Ramkatha: Utpatti Aur Vikas ("The tale of Rama: its origin and development"), proposed that Hanuman worship had its basis in the cults of aboriginal tribes of Central India.[32]

Hanuman is mentioned in the Puranas.[33] A medieval legend posited Hanuman as an avatar of the god Shiva by the 10th century CE (this development possibly started as early as in the 8th century CE).[32][34] Hanuman is mentioned as an avatar of Shiva or Rudra in the medieval era Sanskrit texts like the Mahabhagvata Purana, the Skanda Purana, the Brhaddharma Purana and the Mahanataka among others. This development might have been a result of the Shavite attempts to insert their ishta devata (cherished deity) in the Vaishnavite texts.[32]

Other mythologies, such as those found in South India, present Hanuman as a being who is the union of Shiva and Vishnu, or associated with the origin of Ayyappa.[1] The 17th century Odia work Rasavinoda by Dinakrishnadasa goes on to mention that the three gods – Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva – combined to take to the form of Hanuman.[35]

Late medieval and modern era

Numerous 14th-century and later Hanuman images are found in the ruins of the Hindu Vijayanagara Empire.[10]:64–71

In Valmiki's Ramayana, estimated to have been composed before or in about the 3rd century BCE,[citation needed] Hanuman is an important, creative character as a simian helper and messenger for Rama. The character evolved over time, reflecting regional cultural values. It is, however, in the late medieval era that his profile evolves into more central role and dominance as the exemplary spiritual devotee, particularly with the popular vernacular text Ramcharitmanas by Tulsidas (~ 1575 CE).[36][19] According to scholars such as Patrick Peebles and others, during a period of religious turmoil and Islamic rule of the Indian subcontinent, the Bhakti movement and devotionalism-oriented Bhakti yoga had emerged as a major trend in Hindu culture by the 16th-century, and the Ramcharitmanas presented Rama as a Vishnu avatar, supreme being and a personal god worthy of devotion, with Hanuman as the ideal loving devotee with legendary courage, strength and powers.[12][37]

Hanuman evolved and emerged in this era as the ideal combination of shakti and bhakti.[14] Stories and folk traditions in and after the 17th century, began to reformulate and present Hanuman as a divine being, as a descendent of deities, and as an avatar of Shiva.[37] He emerged as a champion of those religiously persecuted, expressing resistance, a yogi,[10]:85 an inspiration for martial artists and warriors,[10]:57–64 a character with less fur and increasingly human, symbolizing cherished virtues and internal values, and worthy of devotion in his own right.[12][38] Hindu monks morphed into soldiers, and they named their organizations after Hanuman.[39][40] This evolution of Hanuman's character, religious and cultural role as well as his iconography continued through the colonial era and in post-colonial times.[41]

Birth

According to Hindu legends, Hanuman was born to Anjana and father Kesari.[1][42] Hanuman is also called the son of the deity Vayu (Wind god) because of legends associated with Vayu's role in Hanuman's birth. One story mentioned in Eknath's Bhavartha Ramayana (16th century CE) states that when Anjana was worshiping Shiva, the King Dasharatha of Ayodhya was also performing the ritual of Putrakama yagna in order to have children. As a result, he received some sacred pudding (payasam) to be shared by his three wives, leading to the births of Rama, Lakshmana, Bharata, and Shatrughna. By divine ordinance, a kite snatched a fragment of that pudding and dropped it while flying over the forest where Anjana was engaged in worship. Vayu, the Hindu deity of the wind, delivered the falling pudding to the outstretched hands of Anjana, who consumed it. Hanuman was born to her as a result.[42][verification needed]

Anjanadri hills is considered to be the birthplace of lord Hanuman. It is located near Vijayanagara Ruins at Hampi, 70 km from Bellary, a city in Karnataka state of India. Some others believe that Lord Hanuman was born in a cave in Anjani Kund (or Anjani Parbat) in what is now southern Gujarat's tribal-dominated Dangs district.[43][44][45]

Child Hanuman reaches for the Sun thinking it is a fruit by BSP Pratinidhi

Childhood

According to Valmiki's Ramayana, one morning in his childhood, Hanuman was hungry and saw the rising red colored sun. Mistaking it for a ripe fruit, he leapt up to eat it. In one version of the Hindu legend, the king of gods Indra intervened and struck his thunderbolt. It hit Hanuman on his jaw, and he fell to the earth as dead with a broken jaw. His father, Vayu (air), states Ramayana in section 4.65, became upset and withdrew. The lack of air created immense suffering to all living beings. This led lord Shiva, to intervene and resuscitate Hanuman, which in turn prompted Vayu to return to the living beings.As the mistake done by god Indra, he grants Hanuman a wish that his body would be as strong as Indra's Vajra, where as his Vajra can also not harm him. Along with Indra other gods have also granted him wishes such as God Agni granted Hanuman a wish that fire won't harm him, God Varuna granted a wish for Hanuman that water won't harm him, God Vayu granted a wish for Hanuman that he will be as fast as wind and the wind won't harm him. Lord Brahma has also granted Hanuman a wish that he can move at any place where he cannot be stopped at anywhere, Lord Vishnu also grants Hanuman a weapon which is named as "Gada". Hence these wishes make Hanuman a immortal, who has unique powers and strong.[46]

In another Hindu version of his childhood legend, which Lutgendorf states is likely older and also found in Jain texts such as the 8th-century Dhurtakhyana, Hanuman's Icarus-like leap for the sun proves to be fatal and he is burnt to ashes from the sun's heat. His ashes fall onto the earth and oceans.[47] Gods then gather the ashes and his bones from land and, with the help of fishes, from the water and re-assemble him. They find everything except one fragment of his jawbone. His great-grandfather on his mother's side then asks Surya to restore the child to life. Surya returns him to life, but Hanuman is left with a disfigured jaw.[47] Hanuman said to have spend his childhood in Kishkindha.

Some time after this event, Hanuman begins using his supernatural powers on innocent bystanders as simple pranks, until one day he pranks a meditating sage. In fury, the sage curses Hanuman to forget the vast majority of his powers.

Adulthood

There is quite a lot of variation between what happens between his childhood and the events of the Ramayana, but his story becomes much more solid in the events of the Ramayana. After Rama and his brother Lakshmana, searching for Rama's kidnapped wife, Sita, arrive in Kishkindha, the new king, and Rama's newfound ally, the monkey king Sugriva, agrees to send scouts in all four directions to search for Rama's missing wife. To the south, Sugriva sends Hanuman and some others, including the great bear Jambavan. This group travels all the way to the southernmost tip of India, where they encounter the ocean with the island of Lanka (modern day Sri Lanka) visible in the horizon. The group wishes to investigate the island, but none can swim or jump so far (it was common for such supernatural powers to be common amongst characters in these epics). However, Jambavan knows from prior events that Hanuman used to be able to do such a feat with ease, and lifts his curse.[48]

The curse lifted, Hanuman now remembers all of his godlike powers. He is said to have transformed into the size of mountain, and flew across the narrow channel to Lanka. Upon landing, he discovers a city populated by the evil king Ravana and his demon followers, so he shrinks down to the size of an ant and sneaks into the city. After searching the city, he discovers Sita in a grove, guarded by demon warriors. When they all fall asleep, he meets with Sita and discusses how he came to find her. She reveals that Ravana kidnapped her and is forcing her to marry him soon. He offers to rescue her but Sita refuses, stating that her husband must do it (A belief from the time of ancient India).[48][49]

What happens next differs by account, but a common tale is that after visiting Sita, he starts destroying the grove, prompting in his capture. Regardless of the tale, he ends up captured in the court of Ravana himself, who laughs when Hanuman tells him that Rama is coming to take back Sita. Ravana orders his servants to light Hanuman's tail on fire as torture for threatening his safety. However, every time they put on an oil soaked cloth to burn, he grows his tail longer so that more cloths need to be added. This continues until Ravana has had enough and orders the lighting to begin. However, when his tail is lit, he shrinks his tail back and breaks free of his bonds with his superhuman strength. He jumps out a window and jumps from rooftop to rooftop, burning down building after building, until much of the city is ablaze. Seeing this triumph, Hanuman leaves back for India.[48][49]

Upon returning, he tells his scouting party what had occurred, and they rush back to Kishkindha, where Rama had been waiting all along for news. Upon hearing that Sita was safe and was awaiting him, Rama gathered the support of Sugriva's army and marched for Lanka. Thus begins the legendary Battle of Lanka.[48]

Throughout the long battle, Hanuman played a role as a general in the army. During one intense fight, Lakshmana, Rama's brother, was fatally wounded and was thought to die without the aid of an herb from a Himalayan mountain. Hanuman was the only one who could make the journey so quickly, and was thus sent to the mountain. Upon arriving, he discovered that there were many herbs along the mountainside, and did not want to take the wrong herb back. So instead, he grew to the size of a mountain, ripped the mountain from the Earth, and flew it back to the battle. This act is perhaps his most legendary among Hindus.[49]

In the end, Rama revealed his divine powers as the incarnation of the God Vishnu, and slew Ravana and the rest of the demon army. Finally finished, Rama returned to his home of Ayodhya to return to his place as king. After blessing all those who aided him in the battle with gifts, he gave Hanuman his gift, who threw it away. Many court officials, perplexed, were angered by this act. Hanuman replied that rather than needing a gift to remember Rama, he would always be in his heart. Some court officials, still upset, asked him for proof, and Hanuman tore open his chest, which had an image of Rama and Sita on his heart. Now proven as a true devotee, Rama cured him and blessed him with immortality, but Hanuman refused this and asked only for a place at Rama's feet to worship him. Touched, Rama blessed him with immortality anyways, which according to legend, is set only as long as the story of Rama lives on.[48][49]

Centuries after the events of the Ramayana, and during the events of the Mahabharata, Hanuman is now a nearly forgotten demigod living his life in a forest. After some time, his half brother through the god Vayu, Bhima, passes through looking for flowers for his wife. Hanuman senses this and decides to teach him a lesson, as Bhima had been known to be boastful of his superhuman strength (at this point in time supernatural powers were much rarer than in the Ramayana but still seen in the Hindu epics). Bhima encountered Hanuman lying on the ground in the shape of a feeble old monkey. He asked Hanuman to move, but he would not. As stepping over an individual was considered extremely disrespectful in this time, Hanuman suggested lifting his tail up to create passage. Bhima heartily accepted, but could not lift the tail to any avail.[50]

Bhima, humbled, realized that the frail monkey was some sort of deity, and asked him to reveal himself. Hanuman revealed himself, much to Bhima's surprise, and the brother's embraced. Hanuman prophesied that Bhima would soon be a part of a terrible war, and promised his brother that he would sit on the flag of his chariot and shout a battle cry that would weaken the hearts of his enemies. Content, Hanuman left his brother to his search, and after that prophesied war, would not be seen again.[50]

Attributes

Hanuman has many attributes:

Hanuman fetches the herb-bearing mountain, in a print from the Ravi Varma Press, 1910s

Chiranjivi (immortal): various versions of Ramayana and Rama Katha state towards their end, just before Rama and Lakshmana die, that Hanuman is blessed to be immortal. He will be a part of humanity forever, while the story of Rama lives on.[51]

Kurūp and Sundar: he is described in Hindu texts as kurūp (ugly) on the outside, but divinely sundar (beautiful inside).[47]

Kama-rupin: He can shapeshift, become smaller than the smallest, larger than the largest adversary at will.[10]:45–47, 287 He uses this attribute to shrink and enter Lanka, as he searches for the kidnapped Sita imprisoned in Lanka. Later on, he takes on the size of a mountain, blazing with radiance, to show his true power to Sita.[52]

Strength: Hanuman is extraordinarily strong, one capable of lifting and carrying any burden for a cause. He is called Vira, Mahavira, Mahabala and other names signifying this attribute of his. During the epic war between Rama and Ravana, Rama's brother Lakshmana is wounded. He can only be healed and his death prevented by a herb found in a particular Himalayan mountain. Hanuman leaps and finds the mountain. There, states Ramayana, Hanuman finds the mountain is full of many herbs. He doesn't know which one to take. So, he lifts the entire Himalayan mountain and carries it across India to Lanka for Lakshmana. His immense strength thus helps Lakshmana recover from his wound.[10]:6, 44–45, 205–210 This legend is the popular basis for the iconography where he is shown flying and carrying a mountain on his palm.[10]:61

Hanuman showing Rama in His heart

Innovative: Hanuman is described as someone who constantly faces very difficult odds, where the adversary or circumstances threaten his mission with certain defeat and his very existence. Yet he finds an innovative way to turn the odds. For example, after he finds Sita, delivers Rama's message, and persuades her that he is indeed Rama's true messenger, he is discovered by the prison guards. They arrest Hanuman, and under Ravana's orders take him to a public execution. There, the Ravana's guards begin his torture, tie his tail with oiled cloth and put it on fire. Hanuman then leaps, jumps from one palace rooftop to another, thus burning everything down.[10]:140–141, 201

Bhakti: Hanuman is presented as the exemplary devotee (bhakta) of Rama and Sita. The Hindu texts such as the Bhagavata Purana, the Bhakta Mala, the Ananda Ramayana and the Ramacharitmanas present him as someone who is talented, strong, brave and spiritually devoted to Rama.[53] The Rama stories such as the Ramayana and the Ramacharitmanas, in turn themselves, present the Hindu dharmic concept of the ideal, virtuous and compassionate man (Rama) and woman (Sita) thereby providing the context for attributes assigned therein for Hanuman.[54][55]

Learned Yogi: In the late medieval texts and thereafter, such as those by Tulasidas, attributes of Hanuman include learned in Vedanta philosophy of Hinduism, the Vedas, a poet, a polymath, a grammarian, a singer and musician par excellence.[53][1]

Remover of obstacles: in devotional literature, Hanuman is the remover of difficulties.[53]

Texts

Hinduism

Ramayana

Hanuman finds Sita in the ashoka grove, and shows her Rama's ring

The Sundara Kanda, the fifth book in the Ramayana, focuses on Hanuman. Hanuman meets Rama in the last year of the latter's 14-year exile, after the demon king Ravana had kidnapped Sita. With his brother Lakshmana, Rama is searching for his wife Sita. This, and related Rama legends are the most extensive stories about Hanuman.[56][57]

Numerous versions of the Ramayana exist within India. These present variant legends of Hanuman, Rama, Sita, Lakshamana and Ravana. The characters and their descriptions vary, in some cases quite significantly.[58]

Mahabharata

Roadside Hanuman shrine south of Chennai, Tamil Nadu

The Mahabharata is another major epic which has a short mention of Hanuman. In Book 3, the Vana Parva of the Mahabharata, he is presented as a half brother of Bhima, who meets him accidentally on his way to Mount Kailasha. A man of extraordinary strength, Bhima is unable to move Hanuman's tail, making him realize and acknowledge the strength of Hanuman. This story attests to the ancient chronology of the Hanuman character. It is also a part of artwork and reliefs such as those at the Vijayanagara ruins.[59][60]

Other literature

Apart from Ramayana and Mahabharata, Hanuman is mentioned in several other texts. Some of these stories add to his adventures mentioned in the earlier epics, while others tell alternative stories of his life. The Skanda Purana mentions Hanuman in Rameswaram.[61]

In a South Indian version of Shiva Purana, Hanuman is described as the son of Shiva and Mohini (the female avatar of Vishnu), or alternatively his mythology has been linked to or merged with the origin of Swami Ayyappa who is popular in parts of South India.[1]

Hanuman Chalisa

The 16th-century Indian poet Tulsidas wrote Hanuman Chalisa, a devotional song dedicated to Hanuman. He claimed to have visions where he met face to face with Hanuman. Based on these meetings, he wrote Ramcharitmanas, an Awadhi language version of Ramayana.[62]

Buddhism

Hanuman appears with a Buddhist gloss in Tibetan (southwest China) and Khotanese (west China, central Asia and northern Iran) versions of Ramayana. The Khotanese versions have a Jātaka tales-like theme, but are generally similar to the Hindu texts in the storyline and character of Hanuman. The Tibetan version is more embellished, and without attempts to include a Jātaka gloss. Also, in the Tibetan version, novel elements appear such as Hanuman carrying love letters between Rama and Sita, in addition to the Hindu version wherein Rama sends the wedding ring with him as a message to Sita. Further, in the Tibetan version, Rama chides Hanuman for not corresponding with him through letters more often, implying that the monkey-messenger and warrior is a learned being who can read and write letters.[6][63]

In Japan, icons of the divine monkey (Saruta Biko), guards temples such as Saru-gami at Hie Shrine.[64][65]

In the Sri Lankan versions of Ramayana, which are titled after Ravana, the story is less melodramatic than the Indian stories. Many of the legends recounting Hanuman's bravery and innovative ability are found in the Sinhala versions. The stories in which the characters are involved have Buddhist themes, and lack the embedded ethics and values structure according to Hindu dharma.[66] According to Hera Walker, some Sinhalese communities seek the aid of Hanuman through prayers to his mother.[67] In Chinese Buddhist texts, states Arthur Cotterall, myths mention the meeting of the Buddha with Hanuman, as well as Hanuman's great triumphs.[68] According to Rosalind Lefeber, the arrival of Hanuman in East Asian Buddhist texts may trace its roots to the translation of the Ramayana into Chinese and Tibetan in the 6th-century CE.[69]

In both China and Japan, according to Lutgendorf, much like in India, there is a lack of a radical divide between humans and animals, with all living beings and nature assumed to be related to humans. There is no exaltation of humans over animals or nature, unlike the Western traditions. A divine monkey has been a part of the historic literature and culture of China and Japan, possibly influenced by the close cultural contact through Buddhist monks and pilgrimage to India over two millennia.[64] For example, the Japanese text Keiranshuyoshu, while presenting its mythology about a divine monkey, that is the theriomorphic Shinto emblem of Hie shrines, describes a flying white monkey that carries a mountain from India to China, then from China to Japan.[70] Many Japanese shrines and village boundaries, dated from the 8th to the 14th centuries, feature a monkey deity as guardian or intermediary between humans and gods.[64][65]

The Jātaka tales contain Hanuman-like stories.[71] For example, the Buddha is described as a monkey-king in one of his earlier births in the Mahakapi Jātaka, wherein he as a compassionate monkey suffers and is abused, but who nevertheless continues to follow dharma in helping a human being who is lost and in danger.[72][73]

Jainism

Paumacariya (also known as Pauma Chariu or Padmacharit), the Jain version of Ramayana written by Vimalasuri, mentions Hanuman not as a divine monkey, but as a Vidyadhara (a supernatural being, demigod in Jain cosmology).[74][75] He is the son of Pavangati (wind deity) and Anjana Sundari. Anjana gives birth to Hanuman in a forest cave, after being banished by her in-laws. Her maternal uncle rescues her from the forest; while boarding his vimana, Anjana accidentally drops her baby on a rock. However, the baby remains uninjured while the rock is shattered. The baby is raised in Hanuruha, his great-uncle's island kingdom, from which Hanuman gets his name.[10]:51–52 Hanuman's strength is not his own achievement, but attributed to his mother's asceticism.[74] In Jain texts, Hanuman is depicted as the 17th of 24 Kamadevas, the one who is ultimately handsome.[10]:330

There are major differences from the Hindu text : (Hanuman is not celibate), (Rama is a pious Jaina who never kills anyone, and it is Lakshamana who kills Ravana.) (Hanuman is a sexually active personality in the Jain versions, marries princess Anangakusuma, the daughter of Kharadushana and Ravana's sister Chandranakha.) Ravana also presents Hanuman one of his nieces as a second wife.) (After becoming an ally of Sugriva, Hanuman acquires a hundred more wives.) Hanuman becomes a supporter of Rama after meeting him and learning about Sita's kidnapping by Ravana. He goes to Lanka on Rama's behalf, but is unable to convince Ravana to give up Sita. Ultimately, he joins Rama in the war against Ravana and performs several heroic deeds.[10]:50–51 Later Jain texts, such as Uttarapurana (9th century CE) by Gunabhadra and Anjana-Pavananjaya (12th century CE), tell the same story.

(In several versions of the Jain Ramayana story, there are passages that explain to Hanuman, and Rama (called Pauma in Jainism), that attachment to women and pleasures are evil). (Hanuman, in these versions, ultimately renounces all social and material life to become a Jain ascetic).[76]

Sikhism

In Sikhism, the Hindu god Rama has been referred to as Sri Ram Chandar, and the story of Hanuman as a siddha has been influential. After the birth of the martial Sikh Khalsa movement in 1699, during the 18th and 19th centuries, Hanuman was an inspiration and object of reverence by the Khalsa.[7] Some Khalsa regiments brought along the Hanuman image to the battleground. The Sikh texts such as Hanuman Natak composed by Hirda Ram Bhalla, and Das Gur Katha by Kavi Kankan describe the heroic deeds of Hanuman.[77] According to Louis Fenech, the Sikh tradition states that Guru Gobind Singh was a fond reader of the Hanuman Natak text.[7]

During the colonial era, in Sikh seminaries in what is now Pakistan, Sikh teachers were called bhai, and they were required to study the Hanuman Natak, the Hanuman story containing Ramcharitmanas and other texts, all of which were available in Gurmukhi script.[78]

Sri Guru Granth Sahib, the primary Sikh Scripture, outright rejects the validity of supremacy of Hanuman. Bhagat Kabir, a prominent writer of the scripture explicitly states that the being like Hanuman does not know the glory of the divine.

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

ਹਨੂਮਾਨ ਸਰਿ ਗਰੁੜ ਸਮਾਨਾਂ

Hanūmān sar garuṛ samānāʼn.

Beings like Hanumaan, Garura,

ਸੁਰਪਤਿ ਨਰਪਤਿ ਨਹੀ ਗੁਨ ਜਾਨਾਂ

Surpaṯ narpaṯ nahī gun jānāʼn.

Indra the King of the gods and the rulers of humans - none of them know Your Glories, Lord.

— Sri Guru Granth Sahib page 691 .mw-parser-output .nobold{font-weight:normal}

Full Shabad

Southeast Asian texts

The non-Indian versions of Ramayana, such as the Thai Ramakien, mention that Hanuman had relationships with multiple women, including Svayamprabha, Benjakaya (Vibhisana's daughter), Suvannamaccha and even Ravana's wife Mandodari.[32] According to these versions of the Ramayana, Macchanu is the son of Hanuman borne by Suvannamaccha, daughter of Ravana.[79] The Jain text Paumacariya mentions that Hanuman married Lankasundari, the daughter of Lanka's chief defender Bajramukha.[80]

Another legend says that a demigod named Matsyaraja (also known as Makardhwaja or Matsyagarbha) claimed to be his son. Matsyaraja's birth is explained as follows: a fish (matsya) was impregnated by the drops of Hanuman's sweat, while he was bathing in the ocean.[32] According to Parasara Samhita, Hanuman married Suvarchala, the daughter of Surya (the Sun God).[81]

The Hanuman in southeast Asian texts differs from the north Indian Hindu version in various ways in the Burmese Ramayana, such as Rama Yagan, Alaung Rama Thagyin (in the Arakanese dialect), Rama Vatthu and Rama Thagyin, the Malay Ramayana, such as Hikayat Sri Rama and Hikayat Maharaja Ravana, and the Thai Ramayana, such as Ramakien. However, in some cases, the aspects of the story are similar to Hindu versions and Jaina or Buddhist versions of Ramayana found elsewhere on the Indian subcontinent.[82]

Significance and influence

Hanuman became more important in the medieval period and came to be portrayed as the ideal devotee (bhakta) of Rama.[32] Hanuman's life, devotion, celibacy and strength inspired wrestlers in India.[83]

Hanuman in 17th-century

Greater than Rama, is Rama's servant [Hanuman].

— Tulsidas, Ramcharitmanas 7.120.14[84]

According to Philip Lutgendorf, devotionalism to Hanuman and his theological significance emerged long after the composition of the Ramayana, in the 2nd millennium CE. His prominence grew after the arrival of Islamic rule in the Indian subcontinent.[11] He is viewed as the ideal combination of shakti ("strength, heroic initiative and assertive excellence") and bhakti ("loving, emotional devotion to his personal god Rama").[14] Beyond wrestlers, he has been the patron god of other martial arts. He is stated to be a gifted grammarian, meditating yogi and diligent scholar. He exemplifies the human excellences of temperance, faith and service to a cause.[13][15][9]

In 17th-century north and western regions of India, Hanuman emerged as an expression of resistance and dedication against Islamic persecution. For example, the bhakti poet-saint Ramdas presented Hanuman as a symbol of Marathi nationalism and resistance to Mughal Empire.[12]

Hanuman in the colonial and post-colonial era has been a cultural icon, as a symbolic ideal combination of shakti and bhakti, as a right of Hindu people to express and pursue their forms of spirituality and religious beliefs (dharma).[14][85] Political and religious organizations have named themselves after him or his synonyms such as Bajrang.[86][39][40] Political parades or religious processions have featured men dressed up as Hanuman, along with women dressed up as gopis (milkmaids) of god Krishna, as an expression of their pride and right to their heritage, culture and religious beliefs.[87][88] According to some scholars, the Hanuman-linked youth organizations have tended to have a paramilitary wing and have opposed other religions, with a mission of resisting the "evil eyes of Islam, Christianity and Communism", or as a symbol of Hindu nationalism.[89][90]

Iconography

A five-headed panchamukha Hanuman icon. It is found in esoteric tantric traditions that weave Vaishvana and Shaiva ideas, and is relatively uncommon.[91][10]:319, 380–388

Hanuman's iconography shows him either with other central characters of the Ramayana or by himself. If with Rama and Sita, he is shown to the right of Rama, as a devotee bowing or kneeling before them with a Namaste (Anjali Hasta) posture. If alone, he carries weapons such as a big Gada (mace) and thunderbolt (vajra), sometimes in a scene reminiscent of a scene from his life.[1][92]

In the modern era, his iconography and temples have been common. He is typically shown with Rama, Sita and Lakshmana, near or in Vaishnavism temples, as well as by himself usually opening his chest to symbolically show images of Rama and Sita near his heart. He is also popular among the followers of Shaivism.[13]

In north India, aniconic representation of Hanuman such as a round stone has been in use by yogi, as a means to help focus on the abstract aspects of him.[93]

Temples and shrines

41 meters (135 Ft) high Hanuman monument at Paritala, Andhra Pradesh

Hanuman is often worshipped along with Rama and Sita of Vaishnavism, sometimes independently.[19] There are numerous statues to celebrate or temples to worship Hanuman all over India. In some regions, he is considered as an avatar of Shiva, the focus of Shaivism.[19] According to a review by Lutgendorf, some scholars state that the earliest Hanuman murtis appeared in the 8th century, but verifiable evidence of Hanuman images and inscriptions appear in the 10th century in Indian monasteries in central and north India.[10]:60

Wall carvings depicting the worship of Hanuma at Undavalli Caves, Vijaywada

Tuesday and Saturday of every week are particularly popular days at Hanuman temples. Some people keep a partial or full fast on either of those two days and remember Hanuman and the theology he represents to them.[10]:11–12, 101

Major temples and shrines of Hanuman include:

- The oldest known independent Hanuman temple and statue is at Khajuraho, dated to about 922 CE from the Khajuraho Hanuman inscription.[94][10]:59–60

Jakhu temple in Shimla, the capital of Himachal Pradesh. A monumental 108-foot (33-metre) statue of Hanuman marks his temple and is the highest point in Shimla.[95]

- The tallest Hanuman statue is the Veera Abhaya Anjaneya Swami, standing 135 feet tall at Paritala, 32 km from Vijayawada in Andhra Pradesh, installed in 2003.[10]

Chitrakoot in Madhya Pradesh features the Hanuman Dhara temple, which features a panchmukhi statue of Hanuman. It is located inside a forest, and it along with Ramghat that is a few kilometers away, are significant Hindu pilgrimage sites.[96]

- The Peshwa era rulers in 18th century city of Pune provided endowments to more Maruti temples than to temples of other deities such as Shiva, Ganesh or Vitthal.Even in present time there are more Maruti temples in the city and the district than of other deities.[97]

- Other monumental statues of Hanuman are found all over India, such as at the Sholinghur Sri Yoga Narasimha swami temple and Sri Yoga Anjaneyar temple, located in Vellore District. In Maharashtra, a monumental statue is at Nerul, Navi Mumbai. In Bangalore, a major Hanuman statue is at the Ragigudda Anjaneya temple. Similarly, a 32 feet (10 m) idol with a temple exists at Nanganallur in Chennai. At the Hanuman Vatika in Rourkela, Odisha there is 75-foot (23 m) statue of Hanuman.[98]

In India, the annual autumn season Ramlila play features Hanuman, enacted during Navratri by rural artists (above).

- Outside India, a major Hanuman statue has been built by Tamil Hindus near the Batu caves in Malaysia, and an 85-foot (26 m) Karya Siddhi Hanuman statue by colonial era Hindu indentured workers' descendants at Carapichaima in Trinidad and Tobago. Another Karya Siddhi Hanuman Temple has been built in Frisco, Texas in the United States.[99]

Festivals and celebrations

Hanuman is a central character in the annual Ramlila celebrations in India, and seasonal dramatic arts in southeast Asia, particularly in Thailand; and Bali and Java, Indonesia. Ramlila is a dramatic folk re-enactment of the life of Rama according to the ancient Hindu epic Ramayana or secondary literature based on it such as the Ramcharitmanas.[100] It particularly refers to the thousands[101] of dramatic plays and dance events that are staged during the annual autumn festival of Navratri in India.[102] Hanuman is featured in many parts of the folk-enacted play of the legendary war between Good and Evil, with the celebrations climaxing in the Dussehra (Dasara, Vijayadashami) night festivities where the giant grotesque effigies of Evil such as of demon Ravana are burnt, typically with fireworks.[103][104]

The Ramlila festivities were declared by UNESCO as one of the "Intangible Cultural Heritages of Humanity" in 2008. Ramlila is particularly notable in the historically important Hindu cities of Ayodhya, Varanasi, Vrindavan, Almora, Satna and Madhubani – cities in Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh.[103]

Hanuman's birthday is observed by some Hindus as Hanuman Jayanti. It falls in much of India in the traditional month of Chaitra in the lunisolar Hindu calendar, which overlaps with March and April. However, in parts of Kerala and Tamil Nadu, Hanuman Jayanthi is observed in the regional Hindu month of Margazhi, which overlaps with December and January. The festive day is observed with devotees gathering at Hanuman temples before sunrise, and day long spiritual recitations and story reading about the victory of good over evil.[8]

Hanuman in Southeast Asia

Cambodia

Hanuman is a revered heroic figure in Khmer history in southeast Asia. He features predominantly in the Reamker, a Cambodian epic poem, based on the Sanskrit Itihasa Ramayana epic.[105] Intricate carvings on the walls of Angkor Wat depict scenes from the Ramayana including those of Hanuman.[106]

Hanuman statue at Bali, Indonesia

In Cambodia and many other parts of southeast Asia, mask dance and shadow theatre arts celebrate Hanuman with Ream (same as Rama of India). Hanuman is represented by a white mask.[107][108] Particularly popular in southeast Asian theatre are Hanuman's accomplishments as a martial artist Ramayana.[109]

Indonesia

Hanuman is the central character in many of the historic dance and drama art works such as Wayang Wong found in Javanese culture, Indonesia. These performance arts can be traced to at least the 10th century.[110] He has been popular, along with the local versions of Ramayana in other islands of Indonesia such as Java.[111][112]

In major medieval era Hindu temples, archeological sites and manuscripts discovered in Indonesian and Malay islands, Hanuman features prominently along with Rama, Sita, Lakshmana, Vishvamitra and Sugriva.[113][114] The most studied and detailed relief artworks are found in the Candis Panataran and Prambanan.[115][116]

Above is a Thai iconography of Hanuman. He is one of the most popular characters of Ramakien.[117]

Hanuman, along with other characters of the Ramayana, are an important source of plays and dance theatre repertoire at Odalan celebrations and other festivals in Bali.[118]

Thailand

Hanuman has been a historic and popular character of Ramakien in Thai culture. He appears wearing a crown on his head and armor. He is depicted as an albino white, strong character with open mouth in action, sometimes shown carrying a trident. In Ramkien, Hanuman is a devoted soldier of Rama. Unlike in Indian adaptations,

Ramakien is one of the illogical version, "Hanuman" also Know as Celibate god.

But Ramakein not mentioned about he is celibate, because the reason is "Ramayana" & Ramakein are totally different Ramayana is The part of Devotion Sanatana Dharma it's a culture of "India", but Ramakien & other Non Indian Versions of Ramayana are rewritten by the poets. Ramakien is not acceptable version on India because it have lot of false stories about the current characters

according to Paula Richman.[119] Hanuman plays a dominant role in the Thai version of the Ramayana epic.[120]

As in the Indian tradition, Hanuman is the patron of martial arts and an example of courage, fortitude and excellence in Thailand.[121]

In non-religious pop culture

Hanuman was mentioned in the 2018 Marvel Cinematic Universe film, Black Panther, where he is shown to be the central deity of a complex Indo-African religion followed by the Jabari tribe from the fictional African nation of Wakanda.[122] The “Hanuman” reference was removed in India.[123][124]

See also

- Hanuman temples

- Hanuman Chalisa

- Hanuman Jayanti

Hanumanasana, an asana named after Hanuman

Sun Wukong, a Chinese literary character in Wu Cheng'en's masterpiece Journey to the West

- The 6 Ultra Brothers vs. the Monster Army

- Hanuman and the Five Riders

Gray langur, also known as the Hanuman langur

References

^ abcdefghijkl George M. Williams (2008). Handbook of Hindu Mythology. Oxford University Press. pp. 146–148. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Brian A. Hatcher (2015). Hinduism in the Modern World. Routledge. ISBN 9781135046309.

^ ab Bibek Debroy (2012). The Mahabharata: Volume 3. Penguin Books. pp. 184 with footnote 686. ISBN 978-0-14-310015-7.

^ "Hanuman", Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

^ abc Wendy Doniger, Hanuman: Hindu mythology, Encyclopaedia Britannica; For a summary of the Chinese text, see Xiyouji: NOVEL BY WU CHENG’EN

^ ab Susan Whitfield; Ursula Sims-Williams (2004). The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. Serindia Publications. p. 212. ISBN 978-1-932476-13-2.

^ abc Louis E. Fenech; W. H. McLeod (2014). Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-1-4422-3601-1.

^ ab J. Gordon Melton; Martin Baumann (2010). Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, 2nd Edition. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1310–1311. ISBN 978-1-59884-204-3.

^ abc Catherine Ludvik (1994). Hanumān in the Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki and the Rāmacaritamānasa of Tulasī Dāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 2–9. ISBN 978-81-208-1122-5.

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzaaab Philip Lutgendorf (2007). Hanuman's Tale: The Messages of a Divine Monkey. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530921-8. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

^ ab Paula Richman (2010), Review: Lutgendorf, Philip's Hanuman's Tale: The Messages of a Divine Monkey, The Journal of Asian Studies; Vol 69, Issue 4 (Nov 2010), pages 1287-1288

^ abcd Jayant Lele (1981). Tradition and Modernity in Bhakti Movements. Brill Academic. pp. 114–116. ISBN 978-90-04-06370-9.

^ abcd Constance Jones; James D. Ryan (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase. pp. 177–178. ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5.

^ abcd Philip Lutgendorf (2007). Hanuman's Tale: The Messages of a Divine Monkey. Oxford University Press. pp. 26–32, 116, 257–259, 388–391. ISBN 978-0-19-530921-8. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

^ ab Lutgendorf, Philip (1997). "Monkey in the Middle: The Status of Hanuman in Popular Hinduism". Religion. 27 (4): 311–332. doi:10.1006/reli.1997.0095.

^ Lutgendorf, Philip (1994). "My Hanuman Is Bigger Than Yours". History of Religions. 33 (3): 211–245. doi:10.1086/463367.

^ H. S. Walker (1998), Indigenous or Foreign? A Look at the Origins of the Monkey Hero Sun Wukong, Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 81. September 1998, Editor: Victor H. Mair, University of Pennsylvania

^ Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam, ed. India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 68.

^ abcd Peter J. Claus; Sarah Diamond; Margaret Ann Mills (2003). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia : Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka. Taylor & Francis. pp. 280–281. ISBN 978-0-415-93919-5.

^ Sarit Kumar Chaudhuri; Sucheta Sen Chaudhuri (2005). Primitive Tribes in Contemporary India: Concept, Ethnography and Demography. Mittal Publications. p. 45. ISBN 978-81-8324-026-0.

^ J.H. Maronier (2013). Pictures of the Tropics: A Catalogue of Drawings, Water-Colours, Paintings and Sculptures in the Collection of the Royal Institute of Linguistics and Anthropology in Leiden. Springer. p. 127. ISBN 978-94-017-6643-2.

^ R. V. R. Murthy (2005). Andaman and Nicobar Islands: Development and Decentralization. Mittal Publications. p. 20. ISBN 978-81-8324-049-9.

^ Uta Gärtner (1994). Tradition and Modernity in Myanmar. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 317. ISBN 978-3-8258-2186-9.

^ Jonathan H. X. Lee; Kathleen M. Nadeau (2011). Encyclopedia of Asian American Folklore and Folklife. ABC-CLIO. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-313-35066-5.

^ Marijke Klokke (2006). Archaeology: Indonesian Perspective : R.P. Soejono's Festschrift. Yayasan Obor Indonesia. pp. 391–396. ISBN 978-979-26-2499-1.

^ Eugenio Barba; Nicola Savarese (2011). A Dictionary of Theatre Anthropology: The Secret Art of the Performer. Taylor & Francis. pp. 77 with Fig 13. ISBN 978-1-135-17635-8.

^ ऋग्वेद:_सूक्तं_१०.८६, Rigveda, Wikisource

^ abc Philip Lutgendorf (1999), Like Mother, Like Son, Sita and Hanuman, Manushi, No. 114, pages 23-25

^ Legend of Ram–Retold. PublishAmerica. 2012-12-28. pp. 56–. ISBN 978-1-4512-2350-7.

^ Philip Lutgendorf (1999), Like Mother, Like Son, Sita and Hanuman, Manushi, No. 114, pages 22-23

^ Nanditha Krishna (1 January 2010). Sacred Animals of India. Penguin Books India. pp. 178–. ISBN 978-0-14-306619-4.

^ abcdef Camille Bulcke; Dineśvara Prasāda (2010). Rāmakathā and Other Essays. Vani Prakashan. pp. 117–126. ISBN 978-93-5000-107-3. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

^ Swami Parmeshwaranand. Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Puranas, Volume 1. Sarup & Sons. pp. 411–. ISBN 978-81-7625-226-3. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

^ Diana L. Eck (1991). Devotion divine, Bhakti traditions from the regions of India: studies in honour of Charlotte Vaudeville. Egbert Forsten. pp. 69, 62–67. ISBN 978-90-6980-045-5., Quote: "Giving up his Rudra form, Lord Shiva as Hanuman adopted a monkey figure, only in view of his affection for Rama."

^ Shanti Lal Nagar (1999). Genesis and evolution of the Rāma kathā in Indian art, thought, literature, and culture: from the earliest period to the modern times. B.R. Pub. Co. ISBN 978-81-7646-082-8. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

^ Catherine Ludvik (1987). F.S. Growse, ed. The Rāmāyaṇa of Tulasīdāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 723–725. ISBN 978-81-208-0205-6.

^ ab Patrick Peebles (2015). Voices of South Asia: Essential Readings from Antiquity to the Present. Routledge. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-1-317-45248-5.

^ Thomas A. Green. Martial Arts of the World: En Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 467–468. ISBN 978-1-57607-150-2.

^ ab William R. Pinch (1996). Peasants and Monks in British India. University of California Press. pp. 27–28, 64, 158–159. ISBN 978-0-520-91630-2.

^ ab Sarvepalli Gopal (1993). Anatomy of a Confrontation: Ayodhya and the Rise of Communal Politics in India. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 41–46, 135–137. ISBN 978-1-85649-050-4.

^ Philip Lutgendorf (2002), Evolving a monkey: Hanuman, poster art and postcolonial anxiety, Contributions to Indian Sociology, Vol 36, Issue 1-2, pages 71-112

^ ab Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Puranas Vol 2.(D-H) pp=628-631, Swami Parmeshwaranand, Sarup & Sons, 2001,

ISBN 978-81-7625-226-3

^ "Hanumanji was born in Gujarat, govt plans Ram trail in Dang". Ahmedabad: DeshGujarat. September 22, 2009.

^ "Lord Hanuman, a Gujarati!". Ahmedabad: The Times of India. September 22, 2009.

^ Thomas, Melvyn (August 31, 2016). "Dang beckons tourists this monsoon". Surat: The Times of India.

^ Catherine Ludvik (1994). Hanumān in the Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki and the Rāmacaritamānasa of Tulasī Dāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-81-208-1122-5.

^ abc Philip Lutgendorf (2007). Hanuman's Tale: The Messages of a Divine Monkey. Oxford University Press. pp. 188–189. ISBN 978-0-19-530921-8. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

^ abcde Pai, Anant (1978). Valmiki's Ramayana. India: Amar Chitra Katha. pp. 1–96.

^ abcd Pai, Anant (1971). Hanuman. India: Amar Chitra Katha. pp. 1–32.

^ ab Chandrakant, Kamala (1980). Bheema and Hanuman. India: Amar Chitra Katha. pp. 1–32.

^ Joginder Narula (1991). Hanuman, God and Epic Hero: The Origin and Growth of Hanuman in Indian Literary and Folk Tradition. Manohar Publications. pp. 19–21. ISBN 978-81-85054-84-1.

^ Goldman, Robert P. (Introduction, translation and annotation) (1996). The Ramayana of Valmiki: An Epic of Ancient India, Volume V: Sundarakanda. Princeton University Press, New Jersey. 0691066620. pp. 45-47.

^ abc Catherine Ludvik (1994). Hanumān in the Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki and the Rāmacaritamānasa of Tulasī Dāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 12–14. ISBN 978-81-208-1122-5.

^ A Kapoor (1995). Gilbert Pollet, ed. Indian Epic Values: Rāmāyaṇa and Its Impact. Peeters Publishers. pp. 181–186. ISBN 978-90-6831-701-5.

^ Roderick Hindery (1978). Comparative Ethics in Hindu and Buddhist Traditions. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 100–107. ISBN 978-81-208-0866-9.

^ Catherine Ludvik (1987). F.S. Growse, ed. The Rāmāyaṇa of Tulasīdāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 723–728. ISBN 978-81-208-0205-6.

^ Catherine Ludvik (1994). Hanumān in the Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki and the Rāmacaritamānasa of Tulasī Dāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-81-208-1122-5.

^ Peter J. Claus; Sarah Diamond; Margaret Ann Mills (2003). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 509–511. ISBN 978-0-415-93919-5.

^ Dallapiccola, A.L.; Verghese, Anila (2002). "Narrative Reliefs of Bhima and Purushamriga at Vijayanagara". South Asian Studies. 18 (1): 73–76. doi:10.1080/02666030.2002.9628609.

^ J. A. B. van Buitenen (1973). The Mahabharata, Volume 2: Book 2: The Book of Assembly; Book 3: The Book of the Forest. University of Chicago Press. pp. 180, 371, 501–505. ISBN 978-0-226-84664-4.

^ Diana L. Eck (1991). Devotion divine: Bhakti traditions from the regions of India : studies in honour of Charlotte Vaudeville. Egbert Forsten. p. 63. ISBN 978-90-6980-045-5. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

^ Catherine Ludvík (1994). Hanumān in the Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki and the Rāmacaritamānasa of Tulasī Dāsa. Motilal Banarasidas publ. pp. 164–. ISBN 978-81-208-1122-5. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

^ J. L. Brockington (1985). Righteous Rāma: The Evolution of an Epic. Oxford University Press. pp. 264–267, 283–284, 300–303, 312 with footnotes. ISBN 978-0-19-815463-1.

^ abc Philip Lutgendorf (2007). Hanuman's Tale: The Messages of a Divine Monkey. Oxford University Press. pp. 353–354. ISBN 978-0-19-804220-4.

^ ab Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney (1989). The Monkey as Mirror: Symbolic Transformations in Japanese History and Ritual. Princeton University Press. pp. 42–54. ISBN 978-0-691-02846-0.

^ John C. Holt (2005). The Buddhist Visnu: Religious Transformation, Politics, and Culture. Columbia University Press. pp. 138–140. ISBN 978-0-231-50814-8.

^ Hera S. Walker (1998). Indigenous Or Foreign?: A Look at the Origins of the Monkey Hero Sun Wukong, Sino-Platonic Papers, Issues 81-87. University of Pennsylvania. p. 45.

^ Arthur Cotterall (2012). The Pimlico Dictionary Of Classical Mythologies. Random House. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-4481-2996-6.

^ Rosalind Lefeber (1994). The Ramayana of Valmiki: An Epic of Ancient India-Kiskindhakanda. Princeton University Press. pp. 29–31. ISBN 978-0-691-06661-5.

^ Richard Karl Payne (1998). Re-Visioning "Kamakura" Buddhism. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 65–66. ISBN 978-0-8248-2078-7.

^ Philip Lutgendorf (2007). Hanuman's Tale: The Messages of a Divine Monkey. Oxford University Press. pp. 38–41. ISBN 978-0-19-804220-4.

^ Peter D. Hershock (2006). Buddhism in the Public Sphere: Reorienting Global Interdependence. Routledge. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-135-98674-2.

^ Reiko Ohnuma (2017). Unfortunate Destiny: Animals in the Indian Buddhist Imagination. Oxford University Press. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-0-19-063755-2.

^ ab M. Whitney Kelting (2009). Heroic Wives Rituals, Stories and the Virtues of Jain Wifehood. Oxford University Press. p. 249 note 15. ISBN 978-0-19-045286-5.

^ Jose Pereira (2001). Monolithic Jinas. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 36–37, 58. ISBN 978-81-208-2397-6.

^ Eva de Clercq (2008). Colette Caillat and Nalini Balbir, ed. Jaina Studies. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 92–94. ISBN 978-81-208-3247-3.

^ Louis E. Fenech (2013). The Sikh Zafar-namah of Guru Gobind Singh: A Discursive Blade in the Heart of the Mughal Empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 149–150 with note 28. ISBN 978-0-19-993145-3.

^ John Stratton Hawley; Gurinder Singh Mann (1993). Studying the Sikhs: Issues for North America. State University of New York Press. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-0-7914-1426-2.

^ The Ramayana and the Malay shadow-play by Amin Sweeney, Vālmīki. Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. 1972. pp. 238, 246, 440.

^ Truman Simanjuntak (2006). Archaeology: Indonesian Perspective : R.P. Soejono's Festschrift. Yayasan Obor Indonesia. p. 362. ISBN 978-979-26-2499-1. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

^ "Wedding bells toll for Lord Hanuman". The Hindu. 2006-01-04.

^ Uta Gärtner (1994). Tradition and Modernity in Myanmar. LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 305–324. ISBN 978-3-8258-2186-9.

^ Devdutt Pattanaik (1 September 2000). The Goddess in India: The Five Faces of the Eternal Feminine. Inner Traditions * Bear & Company. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-89281-807-5. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

^ Lutgendorf, Philip (1997). "Monkey in the Middle: The Status of Hanuman in Popular Hinduism". Religion. 27 (4): 311. doi:10.1006/reli.1997.0095.

^ Philip Lutgendorf (2002), Evolving a monkey: Hanuman, poster art and postcolonial anxiety, Contributions to Indian Sociology, Vol 36, Issue 1-2, pages 71-110

^ Christophe Jaffrelot (2010). Religion, Caste, and Politics in India. Primus Books. p. 183 note 4. ISBN 978-93-80607-04-7.

^ Christophe Jaffrelot (2010). Religion, Caste, and Politics in India. Primus Books. pp. 332, 389–391. ISBN 978-93-80607-04-7.

^ Daromir Rudnyckyj; Filippo Osella (2017). Religion and the Morality of the Market. Cambridge University Press. pp. 75–82. ISBN 978-1-107-18605-7.

^ Pathik Pathak (2008). Future of Multicultural Britain: Confronting the Progressive Dilemma: Confronting the Progressive Dilemma. Edinburgh University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7486-3546-7.

^ Chetan Bhatt (2001). Hindu nationalism: origins, ideologies and modern myths. Berg. pp. 180–192. ISBN 978-1-85973-343-1.

^ Lutgendorf, Philip (2001). "Five heads and no tale: Hanumān and the popularization of Tantra". International Journal of Hindu Studies. 5 (3): 269–296. doi:10.1007/s11407-001-0003-3.

^ T. A. Gopinatha Rao (1993). Elements of Hindu iconography. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 58, 190–194. ISBN 978-81-208-0878-2.

^ David N. Lorenzen (1995). Bhakti Religion in North India: Community Identity and Political Action. State University of New York Press. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-7914-2025-6.

^ Reports of a Tour in Bundelkhand and Rewa in 1883-84, and of a Tour in Rewa, Bundelkhand, Malwa, and Gwalior, in 1884-85, Alexander Cunningham, 1885

^ The Indian Express, Chandigarh, Tuesday, November 2, 2010, p. 5.

^ Swati Mitra (2012). Temples of Madhya Pradesh. Eicher Goodearth and Government of Madhya Pradesh. p. 41. ISBN 978-93-80262-49-9.

^ Philip Lutgendorf (11 January 2007). Hanuman's Tale: The Messages of a Divine Monkey. Oxford University Press. pp. 239, 24. ISBN 978-0-19-804220-4.

^ Raymond Brady Williams (2001). An introduction to Swaminarayan Hinduism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65422-7. Retrieved May 14, 2009. Page 128

^ New Hindu temple serves Frisco's growing Asian Indian population, Dallas Morning News, Aug 6, 2015

^ James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 389. ISBN 978-0-8239-2287-1.

^ Schechner, Richard; Hess, Linda (1977). "The Ramlila of Ramnagar [India]". The Drama Review: TDR. 21 (3): 51–82. doi:10.2307/1145152. JSTOR 1145152.

^ Encyclopedia Britannica (2015). "Navratri – Hindu festival".

^ ab Ramlila, the traditional performance of the Ramayana, UNESCO

^ Ramlila Pop Culture India!: Media, Arts, and Lifestyle, by Asha Kasbekar. Published by ABC-CLIO, 2006.

ISBN 1-85109-636-1. Page 42.

^ Toni Shapiro-Phim, Reamker, The Cambodian Version of Ramayana, Asia Society

^ Marrison, G. E (1989). "Reamker (Rāmakerti), the Cambodian Version of the Rāmāyaṇa. A Review Article". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (1): 122–129. JSTOR 25212421.

^ Jukka O. Miettinen (1992). Classical Dance and Theatre in South-East Asia. Oxford University Press. pp. 120–122. ISBN 978-0-19-588595-8.

^ Leakthina Chau-Pech Ollier; Tim Winter (2006). Expressions of Cambodia: The Politics of Tradition, Identity and Change. Routledge. pp. 140–141. ISBN 978-1-134-17196-5.

^ James R. Brandon; Martin Banham (1997). The Cambridge Guide to Asian Theatre. Cambridge University Press. pp. 236–237. ISBN 978-0-521-58822-5.

^ Margarete Merkle (2012). Bali: Magical Dances. epubli. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-3-8442-3298-1.

^ J. Kats (1927), The Rāmāyana in Indonesia, Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, Cambridge University Press, Vol. 4, No. 3 (1927), pp. 579-585

^ Malini Saran (2005), The Ramayana in Indonesia: alternate tellings, India International Centre Quarterly, Vol. 31, No. 4 (SPRING 2005), pp. 66-82

^ Willem Frederik Stutterheim (1989). Rāma-legends and Rāma-reliefs in Indonesia. Abhinav Publications. pp. xvii, 5–16 (Indonesia), 17–21 (Malaysia), 34–37. ISBN 978-81-7017-251-2.

^ Marijke Klokke (2006). Archaeology: Indonesian Perspective : R.P. Soejono's Festschrift. Yayasan Obor Indonesia. pp. 391–399. ISBN 978-979-26-2499-1.

^ Andrea Acri; H.M. Creese; A. Griffiths (2010). From Lanka Eastwards: The Ramayana in the Literature and Visual Arts of Indonesia. BRILL Academic. pp. 197–203, 209–213. ISBN 978-90-04-25376-6.

^ Moertjipto (1991). The Ramayana Reliefs of Prambanan. Penerbit Kanisius. pp. 40–42. ISBN 978-979-413-720-8.

^ Paula Richman (1991). Many Rāmāyaṇas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia. University of California Press. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0-520-07589-4.

^ Hildred Geertz (2004). The Life of a Balinese Temple: Artistry, Imagination, and History in a Peasant Village. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 154–165. ISBN 978-0-8248-2533-1.

^ Paula Richman (1991). Many Rāmāyaṇas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia. University of California Press. pp. 38–40. ISBN 978-0-520-07589-4.

^ Amolwan Kiriwat (1997), KHON: MASKED DANCE DRAMA OF THE THAI EPIC RAMAKIEN Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, University of Maine, Advisor: Sandra Hardy, pages 3-4, 7

^ Tony Moore; Tim Mousel (2008). Muay Thai. New Holland. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-1-84773-151-7.

^ O'Neil, Tyler. "'Where Is Your God Now?' 3 Religious Objects of Worship in 'Black Panther'". PJ Media News. PJ. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

^ Amish Tripathi (March 12, 2018). "What India can learn from 'Black Panther'". washingtonpost.com. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

^ Nicole Drum (February 20, 2018). "'Black Panther' Movie Had a Word Censored in India". comicbook.com. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Claus, Peter J.; Sarah Diamond; Margaret Ann Mills (2003). "Hanuman". South Asian folklore. Taylor & Francis. pp. 280–281. ISBN 978-0-415-93919-5.

- Sri Ramakrishna Math (1985): Hanuman Chalisa. Chennai (India): Sri Ramakrishna Math.

ISBN 81-7120-086-9.

Mahabharata (1992). Gorakhpur (India): Gitapress.

Anand Ramayan (1999). Bareily (India): Rashtriya Sanskriti Sansthan.- Swami Satyananda Sarawati: Hanuman Puja. India: Devi Mandir.

ISBN 1-887472-91-6.

The Ramayana Smt. Kamala Subramaniam. Published by Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan (1995).

ISBN 81-7276-406-5

Hanuman - In Art, Culture, Thought and Literature by Shanti Lal Nagar (1995).

ISBN 81-7076-075-5

Further reading

Catherine Ludvik (1994). Hanumān in the Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki and the Rāmacaritamānasa of Tulasī Dāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1122-5.

Helen M. Johnson (1931). Hanumat’s birth and Varuṇa’s subjection (Chapter III of the Jain Ramayana by Hemachandra). Baroda Oriental Institute.

Philip Lutgendorf (2007). Hanuman's Tale: The Messages of a Divine Monkey. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530921-8.

Robert Goldman; Sally Goldman (2006). The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India. Volume V: Sundarakāṇḍa. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-3166-7.

- Vanamali, Mataji Devi (2010). Hanuman: The Devotion and Power of the Monkey God Inner Traditions, USA.

ISBN 1-59477-337-8.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Hanuman |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hanuman. |

Hanuman at Encyclopædia Britannica