Chromatography

Thin layer chromatography is used to separate components of a plant extract, illustrating the experiment with plant pigments that gave chromatography its name

Chromatography is a laboratory technique for the separation of a mixture.

The mixture is dissolved in a fluid called the mobile phase, which carries it through a structure holding another material called the stationary phase. The various constituents of the mixture travel at different speeds, causing them to separate. The separation is based on differential partitioning between the mobile and stationary phases. Subtle differences in a compound's partition coefficient result in differential retention on the stationary phase and thus affect the separation.[1]

Chromatography may be preparative or analytical. The purpose of preparative chromatography is to separate the components of a mixture for later use, and is thus a form of purification. Analytical chromatography is done normally with smaller amounts of material and is for establishing the presence or measuring the relative proportions of analytes in a mixture. The two are not mutually exclusive.[2]

Contents

1 Etymology and pronunciation

2 History

3 Chromatography terms

4 Techniques by chromatographic bed shape

4.1 Column chromatography

4.2 Planar chromatography

4.2.1 Paper chromatography

4.2.2 Thin layer chromatography (TLC)

5 Displacement chromatography

6 Techniques by physical state of mobile phase

6.1 Gas chromatography

6.2 Liquid chromatography

7 Affinity chromatography

7.1 Supercritical fluid chromatography

8 Techniques by separation mechanism

8.1 Ion exchange chromatography

8.2 Size-exclusion chromatography

8.3 Expanded bed adsorption chromatographic separation

9 Special techniques

9.1 Reversed-phase chromatography

9.2 Hydrophobic interaction chromatography

9.3 Two-dimensional chromatography

9.4 Simulated moving-bed chromatography

9.5 Pyrolysis gas chromatography

9.6 Fast protein liquid chromatography

9.7 Countercurrent chromatography

9.8 Periodic counter-current chromatography

9.9 Chiral chromatography

9.10 Aqueous normal-phase chromatography

10 See also

11 References

12 External links

Etymology and pronunciation

Chromatography, pronounced /ˌkroʊməˈtɒɡrəfi/, is derived from Greek χρῶμα chroma, which means "color", and γράφειν graphein, which means "to write".[3]

History

Chromatography was first employed in Russia by the Italian-born scientist Mikhail Tsvet in 1900.[4] He continued to work with chromatography in the first decade of the 20th century, primarily for the separation of plant pigments such as chlorophyll, carotenes, and xanthophylls. Since these components have different colors (green, orange, and yellow, respectively) they gave the technique its name. New types of chromatography developed during the 1930s and 1940s made the technique useful for many separation processes.[5]

Chromatography technique developed substantially as a result of the work of Archer John Porter Martin and Richard Laurence Millington Synge during the 1940s and 1950s, for which they won the 1952 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.[6] They established the principles and basic techniques of partition chromatography, and their work encouraged the rapid development of several chromatographic methods: paper chromatography, gas chromatography, and what would become known as high-performance liquid chromatography. Since then, the technology has advanced rapidly. Researchers found that the main principles of Tsvet's chromatography could be applied in many different ways, resulting in the different varieties of chromatography described below. Advances are continually improving the technical performance of chromatography, allowing the separation of increasingly similar molecules. Chromatography has also been employed as a method to test the potency of cannabis.[7]

Chromatography terms

- The analyte is the substance to be separated during chromatography. It is also normally what is needed from the mixture.

Analytical chromatography is used to determine the existence and possibly also the concentration of analyte(s) in a sample.- A bonded phase is a stationary phase that is covalently bonded to the support particles or to the inside wall of the column tubing.

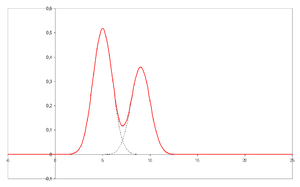

- A chromatogram is the visual output of the chromatograph. In the case of an optimal separation, different peaks or patterns on the chromatogram correspond to different components of the separated mixture.

- Plotted on the x-axis is the retention time and plotted on the y-axis a signal (for example obtained by a spectrophotometer, mass spectrometer or a variety of other detectors) corresponding to the response created by the analytes exiting the system. In the case of an optimal system the signal is proportional to the concentration of the specific analyte separated.

- A chromatograph is equipment that enables a sophisticated separation, e.g. gas chromatographic or liquid chromatographic separation.

Chromatography is a physical method of separation that distributes components to separate between two phases, one stationary (stationary phase), the other (the mobile phase) moving in a definite direction.- The eluate is the mobile phase leaving the column. This is also called effluent.

- The eluent is the solvent that carries the analyte.

- The eluite is the analyte, the eluted solute.

- An eluotropic series is a list of solvents ranked according to their eluting power.

- An immobilized phase is a stationary phase that is immobilized on the support particles, or on the inner wall of the column tubing.

- The mobile phase is the phase that moves in a definite direction. It may be a liquid (LC and Capillary Electrochromatography (CEC)), a gas (GC), or a supercritical fluid (supercritical-fluid chromatography, SFC). The mobile phase consists of the sample being separated/analyzed and the solvent that moves the sample through the column. In the case of HPLC the mobile phase consists of a non-polar solvent(s) such as hexane in normal phase or a polar solvent such as methanol in reverse phase chromatography and the sample being separated. The mobile phase moves through the chromatography column (the stationary phase) where the sample interacts with the stationary phase and is separated.

Preparative chromatography is used to purify sufficient quantities of a substance for further use, rather than analysis.- The retention time is the characteristic time it takes for a particular analyte to pass through the system (from the column inlet to the detector) under set conditions. See also: Kovats' retention index

- The sample is the matter analyzed in chromatography. It may consist of a single component or it may be a mixture of components. When the sample is treated in the course of an analysis, the phase or the phases containing the analytes of interest is/are referred to as the sample whereas everything out of interest separated from the sample before or in the course of the analysis is referred to as waste.

- The solute refers to the sample components in partition chromatography.

- The solvent refers to any substance capable of solubilizing another substance, and especially the liquid mobile phase in liquid chromatography.

- The stationary phase is the substance fixed in place for the chromatography procedure. Examples include the silica layer in thin layer chromatography

- The detector refers to the instrument used for qualitative and quantitative detection of analytes after separation.

Chromatography is based on the concept of partition coefficient. Any solute partitions between two immiscible solvents. When we make one solvent immobile (by adsorption on a solid support matrix) and another mobile it results in most common applications of chromatography. If the matrix support, or stationary phase, is polar (e.g. paper, silica etc.) it is forward phase chromatography, and if it is non-polar (C-18) it is reverse phase.

Techniques by chromatographic bed shape

Column chromatography

Column chromatography is a separation technique in which the stationary bed is within a tube. The particles of the solid stationary phase or the support coated with a liquid stationary phase may fill the whole inside volume of the tube (packed column) or be concentrated on or along the inside tube wall leaving an open, unrestricted path for the mobile phase in the middle part of the tube (open tubular column). Differences in rates of movement through the medium are calculated to different retention times of the sample.[8][9]

In 1978, W. Clark Still introduced a modified version of column chromatography called flash column chromatography (flash).[10][11] The technique is very similar to the traditional column chromatography, except for that the solvent is driven through the column by applying positive pressure. This allowed most separations to be performed in less than 20 minutes, with improved separations compared to the old method. Modern flash chromatography systems are sold as pre-packed plastic cartridges, and the solvent is pumped through the cartridge. Systems may also be linked with detectors and fraction collectors providing automation. The introduction of gradient pumps resulted in quicker separations and less solvent usage.

In expanded bed adsorption, a fluidized bed is used, rather than a solid phase made by a packed bed. This allows omission of initial clearing steps such as centrifugation and filtration, for culture broths or slurries of broken cells.

Phosphocellulose chromatography utilizes the binding affinity of many DNA-binding proteins for phosphocellulose. The stronger a protein's interaction with DNA, the higher the salt concentration needed to elute that protein.[12]

Planar chromatography

Planar chromatography is a separation technique in which the stationary phase is present as or on a plane. The plane can be a paper, serving as such or impregnated by a substance as the stationary bed (paper chromatography) or a layer of solid particles spread on a support such as a glass plate (thin layer chromatography). Different compounds in the sample mixture travel different distances according to how strongly they interact with the stationary phase as compared to the mobile phase. The specific Retention factor (Rf) of each chemical can be used to aid in the identification of an unknown substance.

Paper chromatography

Paper chromatography is a technique that involves placing a small dot or line of sample solution onto a strip of chromatography paper. The paper is placed in a container with a shallow layer of solvent and sealed. As the solvent rises through the paper, it meets the sample mixture, which starts to travel up the paper with the solvent. This paper is made of cellulose, a polar substance, and the compounds within the mixture travel farther if they are non-polar. More polar substances bond with the cellulose paper more quickly, and therefore do not travel as far.

Thin layer chromatography (TLC)

Thin layer chromatography (TLC) is a widely employed laboratory technique used to separate different biochemicals on the basis of their size and is similar to paper chromatography. However, instead of using a stationary phase of paper, it involves a stationary phase of a thin layer of adsorbent like silica gel, alumina, or cellulose on a flat, inert substrate. TLC is very versatile; multiple samples can be separated simultaneously on the same layer, making it very useful for screening applications such as testing drug levels and water purity.[13] Possibility of cross-contamination is low since each separation is performed on a new layer. Compared to paper, it has the advantage of faster runs, better separations, better quantitative analysis, and the choice between different adsorbents. For even better resolution and faster separation that utilizes less solvent, high-performance TLC can be used. An older popular use had been to differentiate chromosomes by observing distance in gel (separation of was a separate step).

Displacement chromatography

The basic principle of displacement chromatography is:

A molecule with a high affinity for the chromatography matrix (the displacer) competes effectively for binding sites, and thus displaces all molecules with lesser affinities.[14]

There are distinct differences between displacement and elution chromatography. In elution mode, substances typically emerge from a column in narrow, Gaussian peaks. Wide separation of peaks, preferably to baseline, is desired for maximum purification. The speed at which any component of a mixture travels down the column in elution mode depends on many factors. But for two substances to travel at different speeds, and thereby be resolved, there must be substantial differences in some interaction between the biomolecules and the chromatography matrix. Operating parameters are adjusted to maximize the effect of this difference. In many cases, baseline separation of the peaks can be achieved only with gradient elution and low column loadings. Thus, two drawbacks to elution mode chromatography, especially at the preparative scale, are operational complexity, due to gradient solvent pumping, and low throughput, due to low column loadings. Displacement chromatography has advantages over elution chromatography in that components are resolved into consecutive zones of pure substances rather than “peaks”. Because the process takes advantage of the nonlinearity of the isotherms, a larger column feed can be separated on a given column with the purified components recovered at significantly higher concentrations.

Techniques by physical state of mobile phase

Gas chromatography

Gas chromatography (GC), also sometimes known as gas-liquid chromatography, (GLC), is a separation technique in which the mobile phase is a gas. Gas chromatographic separation is always carried out in a column, which is typically "packed" or "capillary". Packed columns are the routine work horses of gas chromatography, being cheaper and easier to use and often giving adequate performance. Capillary columns generally give far superior resolution and although more expensive are becoming widely used, especially for complex mixtures. Both types of column are made from non-adsorbent and chemically inert materials. Stainless steel and glass are the usual materials for packed columns and quartz or fused silica for capillary columns.

Gas chromatography is based on a partition equilibrium of analyte between a solid or viscous liquid stationary phase (often a liquid silicone-based material) and a mobile gas (most often helium). The stationary phase is adhered to the inside of a small-diameter (commonly 0.53 – 0.18mm inside diameter) glass or fused-silica tube (a capillary column) or a solid matrix inside a larger metal tube (a packed column). It is widely used in analytical chemistry; though the high temperatures used in GC make it unsuitable for high molecular weight biopolymers or proteins (heat denatures them), frequently encountered in biochemistry, it is well suited for use in the petrochemical, environmental monitoring and remediation, and industrial chemical fields. It is also used extensively in chemistry research.

Liquid chromatography

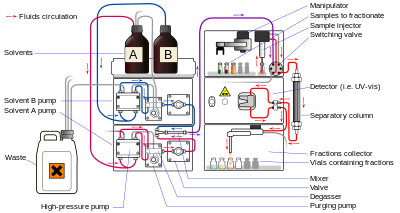

Preparative HPLC apparatus

Liquid chromatography (LC) is a separation technique in which the mobile phase is a liquid. It can be carried out either in a column or a plane. Present day liquid chromatography that generally utilizes very small packing particles and a relatively high pressure is referred to as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

In HPLC the sample is forced by a liquid at high pressure (the mobile phase) through a column that is packed with a stationary phase composed of irregularly or spherically shaped particles, a porous monolithic layer, or a porous membrane. HPLC is historically divided into two different sub-classes based on the polarity of the mobile and stationary phases. Methods in which the stationary phase is more polar than the mobile phase (e.g., toluene as the mobile phase, silica as the stationary phase) are termed normal phase liquid chromatography (NPLC) and the opposite (e.g., water-methanol mixture as the mobile phase and C18 (octadecylsilyl) as the stationary phase) is termed reversed phase liquid chromatography (RPLC).

Specific techniques under this broad heading are listed below.

Affinity chromatography

Affinity chromatography[15] is based on selective non-covalent interaction between an analyte and specific molecules. It is very specific, but not very robust. It is often used in biochemistry in the purification of proteins bound to tags. These fusion proteins are labeled with compounds such as His-tags, biotin or antigens, which bind to the stationary phase specifically. After purification, some of these tags are usually removed and the pure protein is obtained.

Affinity chromatography often utilizes a biomolecule's affinity for a metal (Zn, Cu, Fe, etc.). Columns are often manually prepared. Traditional affinity columns are used as a preparative step to flush out unwanted biomolecules.

However, HPLC techniques exist that do utilize affinity chromatography properties. Immobilized Metal Affinity Chromatography (IMAC)[16][17] is useful to separate aforementioned molecules based on the relative affinity for the metal (i.e. Dionex IMAC). Often these columns can be loaded with different metals to create a column with a targeted affinity.

Supercritical fluid chromatography

Supercritical fluid chromatography is a separation technique in which the mobile phase is a fluid above and relatively close to its critical temperature and pressure.

Techniques by separation mechanism

Ion exchange chromatography

Ion exchange chromatography (usually referred to as ion chromatography) uses an ion exchange mechanism to separate analytes based on their respective charges. It is usually performed in columns but can also be useful in planar mode. Ion exchange chromatography uses a charged stationary phase to separate charged compounds including anions, cations, amino acids, peptides, and proteins. In conventional methods the stationary phase is an ion exchange resin that carries charged functional groups that interact with oppositely charged groups of the compound to retain. There are two types of ion exchange chromatography: Cation-Exchange and Anion-Exchange. In the Cation-Exchange Chromatography the stationary phase has negative charge and the exchangeable ion is a cation, whereas, in the Anion-Exchange Chromatography the stationary phase has positive charge and the exchangeable ion is an anion.[18] Ion exchange chromatography is commonly used to purify proteins using FPLC.

Size-exclusion chromatography

It is one of the most usable form of chromatography. Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) is also known as gel permeation chromatography (GPC) or gel filtration chromatography and separates molecules according to their size (or more accurately according to their hydrodynamic diameter or hydrodynamic volume).

Smaller molecules are able to enter the pores of the media and, therefore, molecules are trapped and removed from the flow of the mobile phase. The average residence time in the pores depends upon the effective size of the analyte molecules. However, molecules that are larger than the average pore size of the packing are excluded and thus suffer essentially no retention; such species are the first to be eluted. It is generally a low-resolution chromatography technique and thus it is often reserved for the final, "polishing" step of a purification. It is also useful for determining the tertiary structure and quaternary structure of purified proteins, especially since it can be carried out under native solution conditions.

Expanded bed adsorption chromatographic separation

An expanded bed chromatographic adsorption (EBA) column for a biochemical separation process comprises a pressure equalization liquid distributor having a self-cleaning function below a porous blocking sieve plate at the bottom of the expanded bed, an upper part nozzle assembly having a backflush cleaning function at the top of the expanded bed, a better distribution of the feedstock liquor added into the expanded bed ensuring that the fluid passed through the expanded bed layer displays a state of piston flow. The expanded bed layer displays a state of piston flow. The expanded bed chromatographic separation column has advantages of increasing the separation efficiency of the expanded bed.

Expanded-bed adsorption (EBA) chromatography is a convenient and effective technique for the capture of proteins directly from unclarified crude sample. In EBA chromatography, the settled bed is first expanded by upward flow of equilibration buffer. The crude feed, a mixture of soluble proteins, contaminants, cells, and cell debris, is then passed upward through the expanded bed. Target proteins are captured on the adsorbent, while particulates and contaminants pass through. A change to elution buffer while maintaining upward flow results in desorption of the target protein in expanded-bed mode. Alternatively, if the flow is reversed, the adsorbed particles will quickly settle and the proteins can be desorbed by an elution buffer. The mode used for elution (expanded-bed versus settled-bed) depends on the characteristics of the feed. After elution, the adsorbent is cleaned with a predefined cleaning-in-place (CIP) solution, with cleaning followed by either column regeneration (for further use) or storage.

Special techniques

Reversed-phase chromatography

Reversed-phase chromatography (RPC) is any liquid chromatography procedure in which the mobile phase is significantly more polar than the stationary phase. It is so named because in normal-phase liquid chromatography, the mobile phase is significantly less polar than the stationary phase. Hydrophobic molecules in the mobile phase tend to adsorb to the relatively hydrophobic stationary phase. Hydrophilic molecules in the mobile phase will tend to elute first. Separating columns typically comprise a C8 or C18 carbon-chain bonded to a silica particle substrate.

Hydrophobic interaction chromatography

Hydrophobic interactions between proteins and the chromatographic matrix can be exploited to purify proteins. In hydrophobic interaction chromatography the matrix material is lightly substituted with hydrophobic groups. These groups can range from methyl, ethyl, propyl, octyl, or phenyl groups.[19] At high salt concentrations, non-polar sidechains on the surface on proteins "interact" with the hydrophobic groups; that is, both types of groups are excluded by the polar solvent (hydrophobic effects are augmented by increased ionic strength). Thus, the sample is applied to the column in a buffer which is highly polar. The eluant is typically an aqueous buffer with decreasing salt concentrations, increasing concentrations of detergent (which disrupts hydrophobic interactions), or changes in pH.

In general, Hydrophobic Interaction Chromatography (HIC) is advantageous if the sample is sensitive to pH change or harsh solvents typically used in other types of chromatography but not high salt concentrations. Commonly, it is the amount of salt in the buffer which is varied. In 2012, Müller and Franzreb described the effects of temperature on HIC using Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) with four different types of hydrophobic resin. The study altered temperature as to effect the binding affinity of BSA onto the matrix. It was concluded that cycling temperature from 50 degrees to 10 degrees would not be adequate to effectively wash all BSA from the matrix but could be very effective if the column would only be used a few times.[20] Using temperature to effect change allows labs to cut costs on buying salt and saves money.

If high salt concentrations along with temperature fluctuations want to be avoided you can use a more hydrophobic to compete with your sample to elute it. [source] This so-called salt independent method of HIC showed a direct isolation of Human Immunoglobulin G (IgG) from serum with satisfactory yield and used Beta-cyclodextrin as a competitor to displace IgG from the matrix.[21] This largely opens up the possibility of using HIC with samples which are salt sensitive as we know high salt concentrations precipitate proteins.

Two-dimensional chromatograph GCxGC-TOFMS at Chemical Faculty of GUT Gdańsk, Poland, 2016

Two-dimensional chromatography

In some cases, the chemistry within a given column can be insufficient to separate some analytes. It is possible to direct a series of unresolved peaks onto a second column with different physico-chemical (chemical classification) properties.[citation needed] Since the mechanism of retention on this new solid support is different from the first dimensional separation, it can be possible to separate compounds by two-dimensional chromatography that are indistinguishable by one-dimensional chromatography.

The sample is spotted at one corner of a square plate, developed, air-dried, then rotated by 90° and usually redeveloped in a second solvent system.

Simulated moving-bed chromatography

The simulated moving bed (SMB) technique is a variant of high performance liquid chromatography; it is used to separate particles and/or chemical compounds that would be difficult or impossible to resolve otherwise. This increased separation is brought about by a valve-and-column arrangement that is used to lengthen the stationary phase indefinitely.

In the moving bed technique of preparative chromatography the feed entry and the analyte recovery are simultaneous and continuous, but because of practical difficulties with a continuously moving bed, simulated moving bed technique was proposed. In the simulated moving bed technique instead of moving the bed, the sample inlet and the analyte exit positions are moved continuously, giving the impression of a moving bed.

True moving bed chromatography (TMBC) is only a theoretical concept. Its simulation, SMBC is achieved by the use of a multiplicity of columns in series and a complex valve arrangement, which provides for sample and solvent feed, and also analyte and waste takeoff at appropriate locations of any column, whereby it allows switching at regular intervals the sample entry in one direction, the solvent entry in the opposite direction, whilst changing the analyte and waste takeoff positions appropriately as well.

Pyrolysis gas chromatography

Pyrolysis–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry is a method of chemical analysis in which the sample is heated to decomposition to produce smaller molecules that are separated by gas chromatography and detected using mass spectrometry.

Pyrolysis is the thermal decomposition of materials in an inert atmosphere or a vacuum. The sample is put into direct contact with a platinum wire, or placed in a quartz sample tube, and rapidly heated to 600–1000 °C. Depending on the application even higher temperatures are used. Three different heating techniques are used in actual pyrolyzers: Isothermal furnace, inductive heating (Curie Point filament), and resistive heating using platinum filaments. Large molecules cleave at their weakest points and produce smaller, more volatile fragments. These fragments can be separated by gas chromatography. Pyrolysis GC chromatograms are typically complex because a wide range of different decomposition products is formed. The data can either be used as fingerprint to prove material identity or the GC/MS data is used to identify individual fragments to obtain structural information. To increase the volatility of polar fragments, various methylating reagents can be added to a sample before pyrolysis.

Besides the usage of dedicated pyrolyzers, pyrolysis GC of solid and liquid samples can be performed directly inside Programmable Temperature Vaporizer (PTV) injectors that provide quick heating (up to 30 °C/s) and high maximum temperatures of 600–650 °C. This is sufficient for some pyrolysis applications. The main advantage is that no dedicated instrument has to be purchased and pyrolysis can be performed as part of routine GC analysis. In this case quartz GC inlet liners have to be used. Quantitative data can be acquired, and good results of derivatization inside the PTV injector are published as well.

Fast protein liquid chromatography

Fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC), is a form of liquid chromatography that is often used to analyze or purify mixtures of proteins. As in other forms of chromatography, separation is possible because the different components of a mixture have different affinities for two materials, a moving fluid (the "mobile phase") and a porous solid (the stationary phase). In FPLC the mobile phase is an aqueous solution, or "buffer". The buffer flow rate is controlled by a positive-displacement pump and is normally kept constant, while the composition of the buffer can be varied by drawing fluids in different proportions from two or more external reservoirs. The stationary phase is a resin composed of beads, usually of cross-linked agarose, packed into a cylindrical glass or plastic column. FPLC resins are available in a wide range of bead sizes and surface ligands depending on the application.

Countercurrent chromatography

An example of a HPCCC system

Countercurrent chromatography (CCC) is a type of liquid-liquid chromatography, where both the stationary and mobile phases are liquids.

The operating principle of CCC equipment requires a column consisting of an open tube coiled around a bobbin. The bobbin is rotated in a double-axis gyratory motion (a cardioid), which causes a variable gravity (G) field to act on the column during each rotation. This motion causes the column to see one partitioning step per revolution and components of the sample separate in the column due to their partitioning coefficient between the two immiscible liquid phases used. There are many types of CCC available today. These include HSCCC (High Speed CCC) and HPCCC (High Performance CCC). HPCCC is the latest and best performing version of the instrumentation available currently.

Periodic counter-current chromatography

In contrast to Countercurrent chromatography (see above), periodic counter-current chromatography (PCC) uses a solid stationary phase and only a liquid mobile phase. It thus is much more similar to conventional affinity chromatography than to countercurrent chromatography. PCC uses multiple columns, which during the loading phase are connected in line. This mode allows for overloading the first column in this series without losing product, which already breaks through the column before the resin is fully saturated. The breakthrough product is captured on the subsequent column(s). In a next step the columns are disconnected from one another. The first column is washed and eluted, while the other column(s) are still being loaded. Once the (initially) first column is re-equilibrated, it is re-introduced to the loading stream, but as last column. The process then continues in a cyclic fashion.

Chiral chromatography

Chiral chromatography involves the separation of stereoisomers. In the case of enantiomers, these have no chemical or physical differences apart from being three-dimensional mirror images. Conventional chromatography or other separation processes are incapable of separating them. To enable chiral separations to take place, either the mobile phase or the stationary phase must themselves be made chiral, giving differing affinities between the analytes. Chiral chromatography HPLC columns (with a chiral stationary phase) in both normal and reversed phase are commercially available.

Aqueous normal-phase chromatography

Aqueous normal-phase (ANP) chromatography is characterized by the elution behavior of classical normal phase mode (i.e. where the mobile phase is significantly less polar than the stationary phase) in which water is one of the mobile phase solvent system components. It is distinguished from hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) in that the retention mechanism is due to adsorption rather than partitioning.[22]

See also

Chromatography portal

Chromatography portal

- Affinity chromatography

- Aqueous normal-phase chromatography

- Binding selectivity

- Chromatofocusing

- Chromatography in blood processing

- Chromatography software

Multicolumn countercurrent solvent gradient purification (MCSGP)- Purnell equation

- Van Deemter equation

- Weak affinity chromatography

References

^ McMurry, John (2011). Organic chemistry: with biological applications (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole. p. 395. ISBN 9780495391470..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Hostettmann, K; Marston, A; Hostettmann, M (1998). Preparative Chromatography Techniques Applications in Natural Product Isolation (Second ed.). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. p. 50. ISBN 9783662036310.

^ "chromatography". Online Etymology Dictionary.

^ Ettre LS, Zlatkis A, eds. (2011-08-26). 75 Years of Chromatography: A Historical Dialogue. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-085817-3.

^ Ettre, L. S.; Sakodynskii, K. I. (March 1993). "M. S. Tswett and the discovery of chromatography II: Completion of the development of chromatography (1903–1910)". Chromatographia. 35 (5–6): 329–338. doi:10.1007/BF02277520.

^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1952". nobelprize.org. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

^ "The Importance of Laboratory Testing for Cannabis Products". 2018-10-25. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

^ Ettre, L. S. (1993). "Nomenclature for chromatography (IUPAC Recommendations 1993)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 65 (4): 819–872. doi:10.1351/pac199365040819.

^ T, Manish. "How does column chromatography work?". BrightMags. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

^ Still, W. C.; Kahn, M.; Mitra, A. (1978). "Rapid chromatographic technique for preparative separations with moderate resolution" (PDF). J. Org. Chem. 43 (14): 2923–2925. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.476.6501. doi:10.1021/jo00408a041.

^ Harwood, Laurence M.; Moody, Christopher J. (1989). Experimental organic chemistry: Principles and Practice (Illustrated ed.). WileyBlackwell. pp. 180–185. ISBN 978-0-632-02017-1.

^ Anfinsen, Christian B.; Edsall, John Tileston; Richards, Frederic Middlebrook, eds. (1976). Advances in Protein Chemistry. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-12-034230-3.

^ Bernard., Fried (2003). Handbook of Thin-Layer Chromatography. Marcel Dekker Inc. ISBN 978-0824748661. OCLC 437068122.

^ Displacement Chromatography 101 Archived 15 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Sachem, Inc. Austin, TX 78737

^ Wilchek, M.; Chaiken, I. (2000). "Chapter 1 An Overview of Affinity Chromatography". In Bailon, P.; Ehrlich, G.K.; Fung, W.J.; Berthold, W. Affinity Chromatography. Methods in Molecular Biology. 147. Humana Press. pp. 1–6. doi:10.1007/978-1-60327-261-2_1. ISBN 978-1-60327-261-2.

^ Singh, Naveen K.; DSouza, Roy N.; Bibi, Noor S.; Fernández-Lahore, Marcelo (2015). "Chapter 16 Direct Capture of His6-Tagged Proteins Using Megaporous Cryogels Developed for Metal-Ion Affinity Chromatography". In Reichelt, S. Affinity Chromatography. Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, N.j.). Methods in Molecular Biology. 1286. pp. 201–212. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-2447-9_16. ISBN 978-1-4939-2447-9. PMID 25749956.

^ Gaberc-Porekar, Vladka K.; Menart, Viktor (2001). "Perspectives of immobilized-metal affinity chromatography". J Biochem Biophys Methods. 49 (1–3): 335–360. doi:10.1016/S0165-022X(01)00207-X.

^ Ninfa, Alexander J (2009). Fundamental Laboratory Approaches for Biochemistry and Biotechnology. ISBN 978-0-470-47131-9.

^ Ninfa AJ, Ballou DP, Benore M (2010). Fundamental Laboratory Approaches for Biochemistry and Biotechnology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley.

^ Müller, Tobias K.H; Franzreb, Matthias (2012). "Suitability of commercial hydrophobic interaction sorbents for temperature-controlled protein liquid chromatography under low salt conditions". Journal of Chromatography A. 1260: 88–96. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2012.08.052. PMID 22954746.

^ Ren, Jun; Yao, Peng; Chen, Jingjing; Jia, Lingyun (2014). "Salt-independent hydrophobic displacement chromatography for antibody purification using cyclodextrin as supermolecular displacer". Journal of Chromatography A. 1369: 98–104. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2014.10.009. PMID 25441076.

^ Kulsing, C; Nolvachai, Y; Marriott, PJ; Boysen, RI; Matyska, MT; Pesek, JJ; Hearn, MT (19 February 2015). "Insights into the origin of the separation selectivity with silica hydride adsorbents". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 119 (7): 3063–9. doi:10.1021/jp5103753. PMID 25656442.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chromatography. |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: School Science/Paper chromatography of amino acids |

- IUPAC Nomenclature for Chromatography

- Overlapping Peaks Program – Learning by Simulations

- Chromatography Videos – MIT OCW – Digital Lab Techniques Manual

- Chromatography Equations Calculators – MicroSolv Technology Corporation