Adolf Hitler's rise to power

Hitler in conversation with Ernst Hanfstaengl and Hermann Göring, 21 June 1932.

Adolf Hitler's rise to power began in Germany in September 1919 when Hitler joined the political party known as the Deutsche Arbeiterpartei – DAP (German Workers' Party). The name was changed in 1920 to the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei – NSDAP (National Socialist German Workers' Party, commonly known as the Nazi Party). This political party was formed and developed during the post-World War I era. It was anti-Marxist and opposed to the democratic post-war government of the Weimar Republic and the Treaty of Versailles; and it advocated extreme nationalism and Pan-Germanism as well as virulent anti-Semitism. Hitler's "rise" can be considered to have ended in March 1933, after the Reichstag adopted the Enabling Act of 1933 in that month. President Paul von Hindenburg had already appointed Hitler as Chancellor on 30 January 1933 after a series of parliamentary elections and associated backroom intrigues. The Enabling Act—when used ruthlessly and with authority—virtually assured that Hitler could thereafter constitutionally exercise dictatorial power without legal objection.

Adolf Hitler rose to a place of prominence in the early years of the party. Being one of the best speakers of the party, he told the other members to either make him leader of the party or he would never return. He was aided in part by his willingness to use violence in advancing his political objectives and to recruit party members who were willing to do the same. The Beer Hall Putsch in November 1923 and the later release of his book Mein Kampf (Translation: My Struggle) introduced Hitler to a wider audience. In the mid-1920s, the party engaged in electoral battles in which Hitler participated as a speaker and organizer,[a] as well as in street battles and violence between the Rotfrontkämpferbund and the Nazis' Sturmabteilung (SA). Through the late 1920s and early 1930s, the Nazis gathered enough electoral support to become the largest political party in the Reichstag, and Hitler's blend of political acuity, deceptiveness and cunning converted the party's non-majority but plurality status into effective governing power in the ailing Weimar Republic of 1933.

Once in power, the Nazis created a mythology surrounding the rise to power, and they described the period that roughly corresponds to the scope of this article as either the Kampfzeit (the time of struggle) or the Kampfjahre (years of struggle).

Contents

1 Early steps (1918–1924)

1.1 From Armistice (November 1918) to party membership (September 1919)

1.2 From early party membership to the Hofbräuhaus Melee (November 1921)

1.3 From Beer Hall Melee to Beer Hall Coup D'État: the abortive Beer Hall Putsch and the ensuing trial

2 Move towards power (1925–1930)

3 Weimar parties fail to halt Nazis

4 Seizure of control (1931–1933)

5 Chancellor to dictator

6 See also

7 References

Early steps (1918–1924)

Adolf Hitler became involved with the fledgling Nazi Party after the First World War, and set the violent tone of the movement early, by forming the Sturmabteilung (SA) paramilitary.[1] Catholic Bavaria resented rule from Protestant Berlin, and Hitler at first saw revolution in Bavaria as a means to power – but an early attempt proved fruitless, and he was imprisoned after the 1923 Munich Beerhall Putsch. He used the time to produce Mein Kampf, in which he argued that the effeminate Jewish-Christian ethic was enfeebling Europe, and that Germany needed a man of iron to restore itself and build an empire.[2] He decided on the tactic of pursuing power through "legal" means.[3]

From Armistice (November 1918) to party membership (September 1919)

After being granted permission from King Ludwig III of Bavaria, 25-year-old Austrian-born Hitler enlisted in a Bavarian regiment of the German army, although he was not yet a German citizen. For over four years (August 1914 – November 1918), Germany was a principal actor in World War I,[b] on the Western Front. Soon after the fighting on the front ended in November 1918,[c] Hitler returned[d] to Munich after the Armistice with no job, no real civilian job skills and no friends. He remained in the Reichswehr and was given a relatively meaningless assignment during the winter of 1918–1919,[e] but was eventually recruited by the Army's Political Department (Press and News Bureau), possibly because of his assistance to the army in investigating the responsibility for the ill-fated Bavarian Soviet Republic.[4][f] He took part in "national thinking" courses under Captain Karl Mayr.[5] Apparently his skills in oratory, as well as his extreme and open anti-Semitism, caught the eye of an approving army officer and he was promoted to an "education officer"—which gave him an opportunity to speak in public.[6][g][h]

In July 1919 Hitler was appointed Verbindungsmann (intelligence agent) of an Aufklärungskommando (reconnaissance commando) of the Reichswehr, both to influence other soldiers and to infiltrate the German Workers' Party (DAP). The DAP had been formed by Anton Drexler, Karl Harrer and others, through amalgamation of other groups, on 5 January 1919 at a small gathering in Munich at the restaurant Fuerstenfelder Hof. While he studied the activities of the DAP, Hitler became impressed with Drexler's antisemitic, nationalist, anti-capitalist and anti-Marxist ideas.[7]

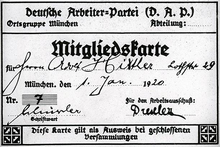

Hitler's membership card for the German Workers' Party (DAP)

During the 12 September 1919 meeting,[i] Hitler took umbrage with comments made by an audience member that were directed against Gottfried Feder, the speaker, a crank economist with whom Hitler was acquainted due to a lecture Feder delivered in an army "education" course.[6][j] The audience member (Hitler in Mein Kampf disparagingly called him the "professor") asserted that Bavaria should be wholly independent from Germany and should secede from Germany and unite with Austria to form a new South German nation.[k] The volatile Hitler arose and scolded the unfortunate Professor Baumann, using his speaking skills and eventually causing Baumann to leave the meeting before its adjournment.[8][9] Impressed with Hitler's oratory skills, Drexler encouraged him to join the DAP. On the orders of his army superiors, Hitler applied to join the party.[10] Within a week, Hitler received a postcard stating he had officially been accepted as a member and he should come to a "committee" meeting to discuss it. Hitler attended the "committee" meeting held at the run-down Alte Rosenbad beer-house.[11] Later Hitler wrote that joining the fledgling party "...was the most decisive resolve of my life. From here there was and could be no turning back. ... I registered as a member of the German Workers' Party and received a provisional membership card with the number 7".[12] Normally, enlisted army personnel were not allowed to join political parties. However, in this case, Hitler had Captain Mayr's permission to join the DAP. Further, Hitler was allowed to stay in the army and receive his weekly pay of 20 gold marks.[13]

From early party membership to the Hofbräuhaus Melee (November 1921)

.mw-parser-output .quotebox{background-color:#F9F9F9;border:1px solid #aaa;box-sizing:border-box;padding:10px;font-size:88%}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft{margin:0.5em 1.4em 0.8em 0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright{margin:0.5em 0 0.8em 1.4em}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.centered{margin:0.5em auto 0.8em auto}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft p,.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright p{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-title{background-color:#F9F9F9;text-align:center;font-size:larger;font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:before{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" “ ";vertical-align:-45%;line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:after{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" ” ";line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .left-aligned{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .right-aligned{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .center-aligned{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .quotebox cite{display:block;font-style:normal}@media screen and (max-width:360px){.mw-parser-output .quotebox{min-width:100%;margin:0 0 0.8em!important;float:none!important}}

Otto Strasser: What is the program of the NSDAP?

Hitler: The program is not the question. The only question is power.

Strasser: Power is only the means of accomplishing the program.

Hitler: These are the opinions of the intellectuals. We need power![14]

By early 1920 the DAP had grown to over 101 members, and Hitler received his membership card as member number 555.[l]

Hitler's considerable oratory and propaganda skills were appreciated by the party leadership. With the support of Anton Drexler, Hitler became chief of propaganda for the party in early 1920 and his actions began to transform the party. He organised their biggest meeting yet of 2,000 people, on 24 February 1920 in the Staatliches Hofbräuhaus in München.[15] There Hitler announced the party's 25-point program (see National Socialist Program).[16] He engineered the name change of the DAP to the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei – NSDAP (National Socialist German Workers' Party), commonly known to the rest of the world as the Nazi Party.[m][17] Hitler designed the party's banner of a swastika in a white circle on a red background.[18] Hitler was later discharged from the army in March 1920 and began working full-time for the NSDAP.[19]

In 1920, a small "hall protection" squad was organised around Emil Maurice.[20] The group was first named the "Order troops" (Ordnertruppen). Later in August 1921, Hitler redefined the group, which became known as the "Gymnastic and Sports Division" of the party (Turn- und Sportabteilung).[21] By the autumn of 1921 the group was being called the Sturmabteilung (Storm Detachment) or SA, and in November 1921 the group was officially known by that name.[22]

Throughout 1920, Hitler began to lecture at Munich's beer halls, particularly the Hofbräuhaus, Sterneckerbräu and Bürgerbräukeller. Only Hitler was able to bring in the crowds for the party speeches and meetings.[23] By this time, the police were already monitoring the speeches, and their own surviving records reveal that Hitler delivered lectures with titles such as Political Phenomenon, Jews and the Treaty of Versailles. At the end of the year, party membership was recorded at 2,000.[24]

In June 1921, while Hitler and Dietrich Eckart were on a fundraising trip to Berlin, a mutiny broke out within the NSDAP in Munich. Members of its executive committee wanted to merge with the rival German Socialist Party (DSP).[25] Hitler returned to Munich on 11 July and angrily tendered his resignation. The committee members realised that the resignation of their leading public figure and speaker would mean the end of the party.[26] Hitler announced he would rejoin on the condition that he would replace Drexler as party chairman, and that the party headquarters would remain in Munich.[27] The committee agreed, and he rejoined the party on 26 July as member 3,680.[27] In the following days, Hitler spoke to several packed houses and defended himself, to thunderous applause. His strategy proved successful: at a general membership meeting, he was granted absolute powers as party chairman, with only one nay vote cast.[28]

On 14 September 1921, Hitler and a substantial number of SA members and other Nazi Party adherents disrupted a meeting at the Löwenbräukeller of the Bavarian League. This federalist organization objected to the centralism of the Weimar Constitution, but accepted its social program. The League was led by Otto Ballerstedt, an engineer whom Hitler regarded as "my most dangerous opponent." One Nazi, Hermann Esser, climbed upon a chair and shouted that the Jews were to blame for the misfortunes of Bavaria, and the Nazis shouted demands that Ballerstedt yield the floor to Hitler.[29] The Nazis beat up Ballerstedt and shoved him off the stage into the audience. Both Hitler and Esser were arrested, and Hitler commented notoriously to the police commissioner, "It's all right. We got what we wanted. Ballerstedt did not speak."[30] Hitler was eventually sentenced to 3 months imprisonment and ended up serving only a little over one month.

On 4 November 1921, the Nazi Party held a large public meeting in the Munich Hofbräuhaus. After Hitler had spoken for some time, the meeting erupted into a melee in which a small company of SA defeated the opposition.[20]

From Beer Hall Melee to Beer Hall Coup D'État: the abortive Beer Hall Putsch and the ensuing trial

Defendants in the Beer Hall Putsch

In 1922 and early 1923, Hitler and the NSDAP formed two organizations that would grow to have huge significance. The first began as the Jungsturm Adolf Hitler and the Jugendbund der NSDAP; they would later become the Hitler Youth.[31][32] The other was the Stabswache (Staff Guard), which in May 1923 was renamed the Stoßtrupp-Hitler (Shock Troop-Hitler).[33] This early incarnation of a bodyguard unit for Hitler would later become the Schutzstaffel (SS).[34]

Inspired by Benito Mussolini's March on Rome in 1922, Hitler decided that a coup d'état was the proper strategy to seize control of the country. In May 1923, elements loyal to Hitler within the army helped the SA to procure a barracks and its weaponry, but the order to march never came.

A pivotal moment came when Hitler led the Beer Hall Putsch, an attempted coup d'état on 8–9 November 1923. Sixteen NSDAP members and four police officers were killed in the failed coup. Hitler was arrested on 11 November 1923.[35] Hitler was put on trial for high treason, gaining great public attention.[36]

The rather spectacular trial began in February 1924. Hitler endeavored to turn the tables and put democracy and the Weimar Republic on trial as traitors to the German people. Hitler was convicted and on 1 April sentenced to five years' imprisonment at Landsberg Prison.[37] Hitler received friendly treatment from the guards; he had a room with a view of the river, wore a tie, regular visitors to his chambers, was allowed mail from supporters and was permitted the use of a private secretary. Pardoned by the Bavarian Supreme Court, he was released from jail on 20 December 1924, against the state prosecutor's objections.[38]

Hitler used the time in Landsberg Prison to consider his political strategy and dictate the first volume of Mein Kampf (My Struggle; originally entitled Four and a Half Years of Struggle against Lies, Stupidity, and Cowardice), principally to his deputy Rudolf Hess.[n] After the putsch the party was banned in Bavaria, but it participated in 1924's two elections by proxy as the National Socialist Freedom Movement. In the German election, May 1924 the party gained seats in the Reichstag, with 6.55% (1,918,329) voting for the Movement. In the German election, December 1924 the National Socialist Freedom Movement (NSFB) (Combination of the Deutschvölkische Freiheitspartei (DVFP) and the Nazi Party (NSDAP)) lost 18 seats, only holding on to 14 seats, with 3% (907,242) of the electorate voting for Hitler's party.

The Barmat Scandal was often used later in Nazi propaganda, both as an electoral strategy and as an appeal to anti-Semitism.

Hitler had determined, after some reflection, that power was to be achieved not through revolution outside of the government, but rather through legal means, within the confines of the democratic system established by Weimar.[citation needed]

For five to six years there would be no further prohibitions of the party (see below Seizure of Control: (1931–1933)).

Move towards power (1925–1930)

In the German election, May 1928 the Party achieved just 12 seats in the Reichstag.[39] The highest provincial gain was again in Bavaria (5.11%), though in three areas the NSDAP failed to gain even 1% of the vote. Overall the NSDAP gained 2.6% (810,100) of the vote.[39] Partially due to the poor results, Hitler decided that Germans needed to know more about his goals. Despite being discouraged by his publisher, he wrote a second book that was discovered and released posthumously as the Zweites Buch. At this time the SA began a period of deliberate antagonism to the Rotfront by marching into Communist strongholds and starting violent altercations.

At the end of 1928, party membership was recorded at 130,000. In March 1929, Erich Ludendorff represented the Nazi Party in the Presidential elections. He gained 280,000 votes (1.1%), and was the only candidate to poll fewer than a million votes. The battles on the streets grew increasingly violent. After the Rotfront interrupted a speech by Hitler, the SA marched into the streets of Nuremberg and killed two bystanders. In a tit-for-tat action, the SA stormed a Rotfront meeting on 25 August and days later the Berlin headquarters of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) itself. In September Goebbels led his men into Neukölln, a KPD stronghold, and the two warring parties exchanged pistol and revolver fire.

The German referendum of 1929 was important as it gained the Nazi Party recognition and credibility it never had before.[40]

On the evening of 14 January 1930, at around ten o'clock, Horst Wessel was fatally shot at point-blank range in the face by two members of the KPD in Friedrichshain.[41] The attack occurred after an argument with his landlady who was a member of the KPD, and contacted one of her Rotfront friends, Albert Hochter, who shot Wessel.[42] Wessel had penned a song months before which would become a Nazi anthem as the Horst-Wessel-Lied. Goebbels seized upon the attack (and the weeks Wessel spent on his deathbed) to publicize the song, and the funeral was used as an anti-Communist propaganda opportunity for the Nazis.[43] In May Goebbels was convicted of "libeling" President Hindenburg and fined 800 marks. It stemmed from a 1929 article by Goebbels in his newspaper Der Angriff. In June, Goebbels was charged with high treason by the prosecutor in Leipzig based on statements Goebbels had made in 1927, but after a four-month investigation it came to naught.[44]

Hitler with Nazi Party members in December, 1930

Against this backdrop, Hitler's party gained a victory in the Reichstag, obtaining 107 seats (18.3%, 6,409,600 votes) in September, 1930.[39] The Nazis became the second largest party in Germany. In Bavaria the party gained 17.9% of the vote, though for the first time this percentage was exceeded by most other provinces: Oldenburg (27.3%), Braunschweig (26.6%), Waldeck (26.5%), Mecklenburg-Strelitz (22.6%), Lippe (22.3%) Mecklenburg-Schwerin (20.1%), Anhalt (19.8%), Thuringen (19.5%), Baden (19.2%), Hamburg (19.2%), Prussia (18.4%), Hessen (18.4%), Sachsen (18.3%), Lubeck (18.3%) and Schaumburg-Lippe (18.1%).

An unprecedented amount of money was thrown behind the campaign. Well over one million pamphlets were produced and distributed; sixty trucks were commandeered for use in Berlin alone. In areas where NSDAP campaigning was less rigorous, the total was as low as 9%. The Great Depression was also a factor in Hitler's electoral success. Against this legal backdrop, the SA began its first major anti-Jewish action on 13 October 1930 when groups of brownshirts smashed the windows of Jewish-owned stores at Potsdamer Platz.[45]

Weimar parties fail to halt Nazis

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 heralded worldwide economic disaster. The Nazis and the Communists made great gains at the 1930 Election.[46] Both the Nazis and Communists between them secured almost 40% of Reichstag seats, which required the moderate parties to consider negotiations with anti-democrats.[47] "The Communists", wrote Bullock, "openly announced that they would prefer to see the Nazis in power rather than lift a finger to save the republic".[48]

The Weimar political parties failed to stop the Nazi rise. Germany's Weimar political system made it difficult for chancellors to govern with a stable parliamentary majority, and successive chancellors instead relied on the president's emergency powers to govern.[49] From 1931 to 1933, the Nazis combined terror tactics with conventional campaigning – Hitler criss-crossed the nation by air, while SA troops paraded in the streets, beat up opponents, and broke up their meetings.[3]

A middle-class liberal party strong enough to block the Nazis did not exist – the People's Party and the Democrats suffered severe losses to the Nazis at the polls. The Social Democrats were essentially a conservative trade union party, with ineffectual leadership. The Catholic Centre Party maintained its voting block, but was preoccupied with defending its own particular interests and, wrote Bullock: "through 1932-3 ... was so far from recognizing the danger of a Nazi dictatorship that it continued to negotiate with the Nazis". The Communists meanwhile were engaging in violent clashes with Nazis on the streets, but Moscow had directed the Communist Party to prioritise destruction of the Social Democrats, seeing more danger in them as a rival for the loyalty of the working class. Nevertheless, wrote Bullock, the heaviest responsibility lay with the German right wing, who "forsook a true conservatism" and made Hitler their partner in a coalition government.[50]

Chancellor Franz von Papen (left) with his eventual successor, the Minister of Defence Kurt von Schleicher.

The Centre Party's Heinrich Brüning was Chancellor from 1930 to 1932. Brüning and Hitler were unable to reach terms of co-operation, but Brüning himself increasingly governed with the support of the President and Army over that of the parliament.[51] The 84-year-old President von Hindenburg, a conservative monarchist, was reluctant to take action to suppress the Nazis, while the ambitious Major-General Kurt von Schleicher, as Minister handling army and navy matters hoped to harness their support.[52] With Schleicher's backing, and Hitler's stated approval, Hindenburg appointed the Catholic monarchist Franz von Papen to replace Brüning as Chancellor in June 1932.[53][54] Papen had been active in the resurgence of the Harzburg Front.[55] He had fallen out with the Centre Party.[56] He hoped ultimately to outmaneuver Hitler.[57]

At the July 1932 Elections, the Nazis became the largest party in the Reichstag, yet without a majority. Hitler withdrew support for Papen and demanded the Chancellorship. He was refused by Hindenburg.[58] Papen dissolved Parliament, and the Nazi vote declined at the November Election.[59] In the aftermath of the election, Papen proposed ruling by decree while drafting a new electoral system, with an upper house. Schleicher convinced Hindenburg to sack Papen, and Schleicher himself became Chancellor, promising to form a workable coalition.[60]

The aggrieved Papen opened negotiations with Hitler, proposing a Nazi-Nationalist Coalition. Having nearly outmaneuvered Hitler, only to be trounced by Schleicher, Papen turned his attentions on defeating Schleicher, and concluded an agreement with Hitler.[61]

Seizure of control (1931–1933)

On 10 March 1931, with street violence between the Rotfront and SA spiraling out of control, breaking all previous barriers and expectations, Prussia re-enacted its ban on brown shirts. Days after the ban SA-men shot dead two communists in a street fight, which led to a ban being placed on the public speaking of Goebbels, who sidestepped the prohibition by recording speeches and playing them to an audience in his absence.

When Hitler's citizenship became a matter of public discussion in 1924 he had a public declaration printed on 16 October 1924: "The loss of my Austrian citizenship is not painful to me, as I never felt as an Austrian citizen but always as a German only . . . . It was this mentality that made me draw the ultimate conclusion and do military service in the German Army."[62] Under the threat of criminal deportation home to Austria, Hitler formally renounced his Austrian citizenship on 7 April 1925, and did not acquire German citizenship until almost seven years later; therefore, he was unable to run for public office.[63] Hitler gained German citizenship after being appointed a Free State of Brunswick government official by Dietrich Klagges, after an earlier attempt by Wilhelm Frick to convey citizenship as a Thuringian police official failed.[64][65][66]

Ernst Röhm, in charge of the SA, put Wolf-Heinrich von Helldorff, a vehement anti-Semite, in charge of the Berlin SA. The deaths mounted, with many more on the Rotfront side, and by the end of 1931 the SA had suffered 47 deaths, and the Rotfront recorded losses of approximately 80.

Street fights and beer hall battles resulting in deaths occurred throughout February and April 1932, all against the backdrop of Adolf Hitler's competition in the presidential election which pitted him against the monumentally popular Hindenburg. In the first round on 13 March, Hitler had polled over 11 million votes but was still behind Hindenburg. The second and final round took place on 10 April: Hitler (36.8% 13,418,547) lost out to Paul von Hindenburg (53.0% 19,359,983) whilst KPD candidate Thälmann gained a meagre percentage of the vote (10.2% 3,706,759). At this time, the Nazi Party had just over 800,000 card-carrying members.

Three days after the presidential elections, the German government banned the NSDAP paramilitaries, the SA and the SS, on the basis of the Emergency Decree for the Preservation of State Authority.[67][68] This action was largely prompted by details that emerged at a trial of SA men for assaulting unarmed Jews in Berlin. After less than a month the law was repealed on 30 May by Franz von Papen, Chancellor of Germany. Such ambivalence about the fate of Jews was supported by the culture of anti-Semitism that pervaded the German public at the time.

In the federal election of July 1932, the NSDAP won 37.3% of the popular vote (13,745,000 votes), an upswing by 19 percentage points, becoming the largest party in the Reichstag, holding 230 out of 608 seats.[39]

Dwarfed by Hitler's electoral gains, the KPD turned away from legal means and increasingly towards violence. One resulting battle in Silesia resulted in the army being dispatched, each shot sending Germany further into a potential all-out civil war. By this time both sides marched into each other's strongholds hoping to spark a rivalry. The attacks continued and reached fever pitch when SA leader Axel Schaffeld was assassinated on 1 August.

As the NSDAP was now the largest party in the Reichstag, they were thus entitled to select the President of the Reichstag and were able to elect Göring for the post.[69] Energised by the success, Hitler asked to be made chancellor. Hitler was offered the job of vice-chancellor by Chancellor Papen at the behest of President Hindenburg, but he refused. Hitler saw this offer as placing him in a position of "playing second fiddle" in the government.[70]

Göring, in his position of Reichstag president, asked that decisive measures be taken by the government over the spate in murders of NSDAP members. On 9 August, amendments were made to the Reichstrafgesetzbuch statute on 'acts of political violence', increasing the penalty to 'lifetime imprisonment, 20 years hard labour or death'. Special courts were announced to try such offences. When in power less than half a year later, Hitler would use this legislation against his opponents with devastating effect.

The law was applied almost immediately but did not bring the perpetrators behind the recent massacres to trial as expected. Instead, five SA men who were alleged to have murdered a KPD member in Potempa (Upper Silesia) were tried. Hitler appeared at the trial as a defence witness, but on 22 August the five were convicted and sentenced to death. On appeal, this sentence was commuted to life imprisonment in early September. They would serve just over four months before Hitler freed all imprisoned Nazis in a 1933 amnesty.

The Nazi Party lost 35 seats in the November 1932 election, but remained the Reichstag's largest party, with 196 seats (33.09%). The Social Democrats (SPD) won 121 seats (20.43%) and the Communists (KPD) won 100 (16.86%).

The Comintern described all moderate left-wing parties as "social fascists", and urged the Communists to devote their energies to the destruction of the moderate left. As a result, the KPD, following orders from Moscow, rejected overtures from the Social Democrats to form a political alliance against the NSDAP.

After Chancellor Papen left office, he secretly told Hitler that he still held considerable sway with President Hindenburg and that he would make Hitler chancellor as long as he, Papen, could be the vice chancellor. Another notable event was the publication of the Industrielleneingabe, a letter signed by 22 important representatives of industry, finance and agriculture, asking Hindenburg to appoint Hitler as chancellor.

Hindenburg reluctantly agreed to appoint Hitler as chancellor after the parliamentary elections of July and November 1932 had not resulted in the formation of a majority government. Hitler headed a short-lived coalition government formed by the NSDAP and the German National People's Party (DNVP).

On 30 January 1933, the new cabinet was sworn in during a brief ceremony in Hindenburg's office. The NSDAP gained three posts: Hitler was named chancellor, Wilhelm Frick Minister of the Interior, and Hermann Göring, Minister Without Portfolio (and Minister of the Interior for Prussia).[71][72] The SA and SS led torchlit parades throughout Berlin.

It is this event that would become termed Hitler's Machtergreifung ("seizure of power"). The term was originally used by some Nazis to suggest a revolutionary process,[73] though Hitler, and others, used the word Machtübernahme ("take-over of power"), reflecting that the transfer of power took place within the existing constitutional framework[73] and suggesting that the process was legal.[74][75]

Papen was to serve as Vice-Chancellor in a majority conservative Cabinet – still falsely believing that he could "tame" Hitler.[54] Initially, Papen did speak out against some Nazi excesses. However, after narrowly escaping death in the Night of the Long Knives in 1934, he no longer dared criticise the regime and was sent off to Vienna as German ambassador.[76]

Both within Germany and abroad initially there were few fears that Hitler could use his position to establish his later dictatorial single-party regime. Rather, the conservatives that helped to make him chancellor were convinced that they could control Hitler and "tame" the Nazi Party while setting the relevant impulses in the government themselves; foreign ambassadors played down worries by emphasizing that Hitler was "mediocre" if not a bad copy of Mussolini; even SPD politician Kurt Schumacher trivialized Hitler as a "Dekorationsstück" ("piece of scenery/decoration") of the new government. German newspapers wrote that, without doubt, the Hitler-led government would try to fight its political enemies (the left-wing parties), but that it would be impossible to establish a dictatorship in Germany because there was "a barrier, over which violence cannot proceed" and because of the German nation being proud of "the freedom of speech and thought". Theodor Wolff of Frankfurter Zeitung wrote:[77]

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

It is a hopeless misjudgement to think that one could force a dictatorial regime upon the German nation. [...] The diversity of the German people calls for democracy.

— Theodor Wolff in Frankfurter Zeitung, Jan 1933

Even within the Jewish German community, in spite of Hitler not hiding his ardent antisemitism, the worries appear to have been limited. In a declaration of January 30, the steering committee of the central Jewish German organization (Centralverein deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens) wrote that "as a matter of course" the Jewish community faces the new government "with the largest mistrust", but at the same they were convinced that "nobody would dare to touch [their] constitutional rights". The Jewish German newspaper Jüdische Rundschau wrote on Jan 31st:[78]

... that also within the German nation still the forces are active that would turn against a barbarian anti-Jewish policy.

— Jüdische Rundschau, Jan 31st, 1933

However a growing number of keen observers, like Sir Horace Rumbold, British Ambassador in Berlin, began to revise their opinions. On 22 February 1933, he wrote, "Hitler may be no statesman but he is an uncommonly clever and audacious demagogue and fully alive to every popular instinct," and he informed the Foreign Office that he had no doubt that the Nazis had "come to stay."[79] On receiving the dispatch Robert Vansittart, Permanent Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, concluded that if Hitler eventually gained the upper hand, "then another European war [was] within measurable distance."[80]

With Germans who opposed Nazism failing to unite against it, Hitler soon moved to consolidate absolute power.

At the risk of appearing to talk nonsense I tell you that the National Socialist movement will go on for 1,000 years! ... Don't forget how people laughed at me 15 years ago when I declared that one day I would govern Germany. They laugh now, just as foolishly, when I declare that I shall remain in power!

— Adolf Hitler to a British correspondent in Berlin, June 1934[81]

Chancellor to dictator

Adolf Hitler addressing the Reichstag on 23 March 1933. Seeking assent to the Enabling Act, Hitler offered the possibility of friendly co-operation, promising not to threaten the Reichstag, the President, the States or the Churches if granted the emergency powers.

Following the Reichstag fire, the Nazis began to suspend civil liberties and eliminate political opposition. The Communists were excluded from the Reichstag. At the March 1933 elections, again no single party secured a majority. Hitler required the vote of the Centre Party and Conservatives in the Reichstag to obtain the powers he desired. He called on Reichstag members to vote for the Enabling Act on 24 March 1933. Hitler was granted plenary powers "temporarily" by the passage of the Act.[82] The law gave him the freedom to act without parliamentary consent and even without constitutional limitations.[83]

Employing his characteristic mix of negotiation and intimidation, Hitler offered the possibility of friendly co-operation, promising not to threaten the Reichstag, the President, the States or the Churches if granted the emergency powers. With Nazi paramilitary encircling the building, he said: "It is for you, gentlemen of the Reichstag to decide between war and peace".[82] The Centre Party, having obtained promises of non-interference in religion, joined with conservatives in voting for the Act (only the Social Democrats voted against).[84]

The Act allowed Hitler and his Cabinet to rule by emergency decree for four years, though Hindenburg remained President.[85] Hitler immediately set about abolishing the powers of the states and the existence of non-Nazi political parties and organisations. Non-Nazi parties were formally outlawed on 14 July 1933, and the Reichstag abdicated its democratic responsibilities.[86] Hindenburg remained commander-in-chief of the military and retained the power to negotiate foreign treaties.

The Act did not infringe upon the powers of the President, and Hitler would not fully achieve full dictatorial power until after the death of Hindenburg in August 1934.[87] Journalists and diplomats wondered whether Hitler could appoint himself President, who might succeed him as Chancellor, and what the army would do. Hitler combined the two positions, so that all governmental power lay in his hands. All soldiers took the Hitler Oath on the day of Hindenburg's death, swearing "unconditional obedience" to Hitler.[88]

See also

- Early timeline of Nazism

- Gleichschaltung

- Poison Kitchen

- Political views of Adolf Hitler

- Weimar paramilitary groups

- Weimar political parties

- Day of Potsdam

References

Informational notes

^ He could not, at this time, run for political office in Germany, as he was not then a German citizen. Shirer 1960, pp. 130–131.

^ Despite his receipt of several medals and decorations (including twice with the prestigious Iron Cross, both First and Second Class), Hitler was promoted in rank only once, to corporal (Gefreiter). Toland 1976, pp. 84–88.

^ The Armistice, ceasing active hostilities, was signed and effective 11 November 1918. Hitler, in hospital at the time, was informed of the upcoming cease-fire and the other consequences of Germany's defeat and surrender in the field—including Kaiser Wilhelm II's abdication, and a revolution leading to the proclamation of a republic in Berlin to replace the centuries-old Hohenzollern monarchy—on Sunday morning, 10 November, by a pastor attending to patients. Days after digesting this traumatic news, by his own account Hitler made his decision: "... my own fate became known to me ... I ... decided to go into politics." Hitler 1999, p. 206.

^ Hitler, having been born in the defunct Austro-Hungarian Empire to Austrian parents, was not a German citizen, but had managed to enlist in a Bavarian regiment, where he served on the front lines as a runner. He was wounded twice in action; at the time of the Armistice, he was recovering in a German hospital (in Pomerania northeast of Berlin) from temporary blindness that had resulted from a mid-October British gas attack at the last Battle of Ypres. Shirer 1960, pp. 28–30; Toland 1976, p. 86.

^ Guard duty at a POW camp to the East, near the Austrian border. The prisoners were Russian, and Hitler had volunteered for the posting. Shirer 1960, p. 34; Toland 1976, p. xx.

^ Toland suggests that Hitler's assignment to this department was partially a reward for his "exemplary" service in the front lines, and partially because the responsible officer felt sorry for Hitler as having no friends, but being very willing to do whatever the army required. Toland 1976, p. xx.

^ Apparently someone in an army "educational session" had made a remark that Hitler deemed "pro-Jewish" and Hitler reacted with characteristic ferocity. Shirer states that Hitler had attracted the attention of a right-wing university professor who was engaged to educate enlisted men in "proper" political belief, and that the professor's recommendation to an officer resulted in Hitler's advancement. Shirer 1960, p. 35.

^ "I was offered the opportunity of speaking before a larger audience; and ... it was now corroborated: I could 'speak.' No task could make me happier than this; ... I was able to perform useful services to ... the army. ... [I]n ... my lectures I led many hundreds ... of comrades back to their people and fatherland." Hitler 1999, pp. 215–216.

^ Held, like so many meetings of the period, in a beer cellar, this time the Sterneckerbrau. Hitler 1999, p. 218.

^ Feder had formed the German Fighting League for the Breaking of Interest Slavery. The notion of "Breaking Interest Slavery" was, by Hitler's account, a "powerful slogan for this coming struggle." Hitler 1999, p. 213.

^ According to Shirer, the seemingly preposterous "South German nation" idea actually had some popularity in Munich in the politically raucous atmosphere of Bavaria following the war. Shirer 1960, p. 36.

^ The membership numbers were artificially started at 501 because the DAP wanted to make itself look larger than it actually was. The membership numbers were also apparently issued alphabetically, and not chronologically, so one cannot infer that Hitler was in fact the party's 55th member. Toland 1976, p. 131. In a Hitler speech shown in Triumph of the Will, Hitler makes explicit reference to his being the seventh party member and he notes the same in Mein Kampf. Hitler 1999, p. 224.

^ The word "Nazi" is a contraction for Nationalsozialistische, but this contraction was not used by the party itself.

^ Hess participated in the putsch, but escaped police custody following its abortive end. He initially fled to Austria, but later turned himself in to the authorities. Nesbit & van Acker 2011, pp. 18–19.

Citations

^ Shadows of the Dictators 1989, p. 25.

^ Shadows of the Dictators 1989, p. 27.

^ ab Shadows of the Dictators 1989, p. 28.

^ Shirer 1960, p. 34.

^ Kershaw 2008, pp. 72–74.

^ ab Shirer 1960, p. 35.

^ Kershaw 2008, p. 82.

^ Hitler 1999, p. 219.

^ Kershaw 2008, p. 75.

^ Evans 2003, p. 170.

^ Kershaw 2008, pp. 75, 76.

^ Hitler 1999, p. 224.

^ Kershaw 2008, p. 76.

^ Toland 1976, p. 106.

^ Kershaw 2008, p. 86.

^ Kershaw 2008, pp. 85, 86.

^ Zentner & Bedürftig 1997, p. 629.

^ Kershaw 2008, pp. 87, 88.

^ Kershaw 2008, p. 93.

^ ab Hoffmann 2000, p. 50.

^ Shirer 1960, p. 42.

^ Campbell 1998, pp. 19, 20.

^ Kershaw 2008, p. 88, 89.

^ Kershaw 2008, p. 89.

^ Kershaw 2008, pp. 100, 101.

^ Kershaw 2008, p. 102.

^ ab Kershaw 2008, p. 103.

^ Kershaw 2008, pp. 83, 103.

^ Toland 1976, pp. 112–113.

^ Toland 1976, p. 113.

^ Lepage 2008, p. 21.

^ Zentner & Bedürftig 1997, p. 431.

^ Weale 2010, p. 16.

^ Weale 2010, pp. 26–29.

^ Kershaw 2008, p. 131.

^ Shirer 1960, p. 75.

^ Fulda 2009, pp. 68–69.

^ Kershaw 1999, p. 239.

^ abcd Kolb 2005, pp. 224–225.

^ Nicholls, A. J. (2000) Weimar and the Rise of Hitler. London: Palgrave MacMillan. p.138 .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 9780312233518

^ Siemens 2013, p. 3.

^ Burleigh 2000, pp. 118–119.

^ Evans 2003, pp. 266–268.

^ Thacker 2010, pp. 111–112.

^ Hakim 1995, p. [page needed].

^ Fulbrook 1991, p. 55.

^ Bullock 1991, p. 118.

^ Bullock 1991, p. 138.

^ Bullock 1991, pp. 92–94.

^ Bullock 1991, pp. 138–139.

^ Bullock 1991, p. 90.

^ Bullock 1991, p. 92.

^ Bullock 1991, p. 110.

^ ab Encyclopædia Britannica.

^ Bracher 1991, p. 254.

^ Bullock 1991, p. 112.

^ Bullock 1991, pp. 113–114.

^ Bullock 1991, pp. 117–123.

^ Bullock 1991, pp. 117–124.

^ Bullock 1991, p. 128.

^ Bullock 1991, p. 132.

^ Hamann 2010, p. 402.

^ Shirer 1960, p. 130.

^ Speer, Albert (1995). Inside the Third Reich. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 109. ISBN 9781842127353.

^ http://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/chap16_part09.asp FRICK'S PARTICIPATION IN PROMOTING THE NAZI CONSPIRATORS' ACCESSION TO POWER.

^ Gunther, John (1940). Inside Europe. New York: Harper & Brothers. pp. 28–29.

^

"1932: Chronik" [1932: Timeline] (in German). Deutsches Historisches Museum. Retrieved 2012-04-06.13. 4. Auf Grundlage der von Hindenburg erlassenen Notverordnung "zur Sicherung der Staatsautorität" verbietet Brüning SA und Schutzstaffel (SS). Die Regierung befürchtet einen Putschversuch der rechtsradikalen Organisationen.

^ "April 1932: SA and SS banned". Federal Chancellor Willy Brandt Foundation. Retrieved 2012-04-06.Basing his actions on the 'Emergency Decree for the Preservation of State Authority', Reich Defence Minister Wilhelm Groener bans Hitler's Sturmabteilung (SA) as well as his Schutzstaffel (SS) on 13 April 1932.

^ Evans 2003, p. 297.

^ Kershaw 2008, pp. 233, 234.

^ Shirer 1960, p. 184.

^ Manvell & Fraenkel 2011, p. 92.

^ ab 2015, p. 6.

^ Evans 2005, pp. 569, 580f.

^ Frei 1983.

^ Evans 2005, pp. 33–34.

^

"Ruhig abwarten!" [Calmly wait!] (in German). Die Zeit Online. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

^ "Ruhig abwarten!" [Calmly wait!] (in German). Die Zeit Online. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

^ Kershaw, Ian, Making Friends with Hitler: Lord Londonderry and Britain's Road to War, Penguin, 2012,

ISBN 9780241959213, 512 p.

^ Liebmann, George, Diplomacy Between the Wars: Five Diplomats and the Shaping of the Modern World, I.B.Tauris, 2008,

ISBN 9780857712110, 288 p., p. 74.

^ Time 1934.

^ ab Bullock 1991, pp. 147–148.

^ Hoffmann 1977, p. 7.

^ Bullock 1991, pp. 138, 148.

^ Evans 2003, p. 354.

^ Shirer 1960, pp. 200–201.

^ Shirer 1960, pp. 226–227.

^ Gunther, John (1940). Inside Europe. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 59.

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Bracher, Karl Dietrich (1991). The German Dictatorship: The Origins, Structure, and Consequences of National Socialism. Penguin History Series. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-013724-8.

Bullock, Alan (1991) [1962]. Hitler: A Study in Tyranny. New York; London: Harper Perennial. ISBN 1-56852-036-0.

Burleigh, Michael (2000). The Third Reich: A New History. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 0-8090-9326-X.

Campbell, Bruce (1998). The SA Generals and The Rise of Nazism. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2047-0.

Encyclopædia Britannica. "Franz von Papen". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

Evans, Richard J. (2003). The Coming of the Third Reich. New York; Toronto: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-303469-8.

Evans, Richard J. (2003). The Coming of the Third Reich. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 0-7139-9648-X.

Evans, Richard J. (2005). Das Dritte Reich – Aufstieg [The Coming Of The Third Reich] (in German). Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag. ISBN 3-423-34191-2.

Frei, Norbert (1983). "Machtergreifung – Anmerkungen zu einem historischen Begriff]" [Machtergreifung – Notes on a historical term] (PDF). Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte (VfZ) (in German) (31): 136–145.

Fulbrook, Mary (1991). The Fontana History of Germany: 1918–1990: The Divided Nation. Fontana Press.

Fulda, Bernhard (2009). Press and Politics in the Weimar Republic. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954778-4.

Hakim, Joy (1995). A History of Us: War, Peace and All That Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509514-6.

Hamann, Brigitte (2010). Hitler's Vienna: A Portrait of the Tyrant as a Young Man. Tauris Parke. ISBN 978-1848852778.

Hitler, Adolf (1999) [1925]. Mein Kampf. New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-92503-4.

Hoffmann, Peter (1977). The History of the German Resistance 1933–1945 (First English ed.). London: McDonald & Jane's.

Hoffmann, Peter (2000). Hitler's Personal Security: Protecting the Führer 1921–1945. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-30680-947-7.

Kershaw, Ian (1999) [1998]. Hitler: 1889–1936: Hubris. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-04671-7.

Kershaw, Ian (2008). Hitler: A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-06757-2.

Kolb, Eberhard (2005) [1984]. The Weimar Republic. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-34441-8.

Lepage, Jean-Denis G.G. (2008). Hitler Youth, 1922–1945: An Illustrated History. Jefferson, NC; London: McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0786439355.

Manvell, Roger; Fraenkel, Heinrich (2011) [1962]. Goering: The Rise and Fall of the Notorious Nazi Leader. London: Skyhorse. ISBN 978-1-61608-109-6.

Nesbit, Roy Conyers; van Acker, Georges (2011) [1999]. The Flight of Rudolf Hess: Myths and Reality. Stroud: History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-4757-2.

Shirer, William L. (1960). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-62420-0.

Siemens, Daniel (2013). The Making of a Nazi Hero: The Murder and Myth of Horst Wessel. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0857733139.

Stachura, Peter D., ed. (2015) [First published in 1983 by Allen & Unwin]. "Introduction: Weimar National Socialism and Historians". The Nazi Machtergreifung. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-75554-0..

Staff (1989). Shadows of the Dictators: AD 1925–50. Amsterdam: Time-Life Books. ISBN 0-7054-0990-2.

Staff (2 July 1934). "Germany: Second Revolution?". Time Magazine. Time. Archived from the original on 17 April 2008. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

Thacker, Toby (2010) [2009]. Joseph Goebbels: Life and Death. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-27866-0.

Toland, John (1976). Adolf Hitler. New York: Doubleday & Company. ISBN 0-385-03724-4.

Weale, Adrian (2010). The SS: A New History. London: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1408703045.

Zentner, Christian; Bedürftig, Friedemann (1997) [1991]. The Encyclopedia of the Third Reich. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-3068079-3-0.