Thermal insulation

Mineral wool Insulation, 1600 dpi scan

Thermal insulation is the reduction of heat transfer (i.e. the transfer of thermal energy between objects of differing temperature) between objects in thermal contact or in range of radiative influence. Thermal insulation can be achieved with specially engineered methods or processes, as well as with suitable object shapes and materials.

Heat flow is an inevitable consequence of contact between objects of different temperature. Thermal insulation provides a region of insulation in which thermal conduction is reduced or thermal radiation is reflected rather than absorbed by the lower-temperature body.

The insulating capability of a material is measured as the inverse of thermal conductivity (k). Low thermal conductivity is equivalent to high insulating capability (Resistance value). In thermal engineering, other important properties of insulating materials are product density (ρ) and specific heat capacity (c).

Contents

1 Definition

1.1 Insulation of cylinders

2 Applications

2.1 Clothing and natural animal insulation in birds and mammals

2.2 Buildings

2.3 Mechanical systems

2.4 Refrigeration

2.5 Spacecraft

2.6 Automotive

3 Factors influencing performance

4 Calculating requirements

5 See also

6 References

7 Further reading

8 External links

Definition

Thermal conductivity k is measured in watts-per-meter per kelvin (W·m−1·K−1). This is because heat transfer, measured as Power, has been found to be (approximately) proportional to

- difference of temperature ΔT{displaystyle Delta T}

;

- the surface area of thermal contact A{displaystyle A}

- the inverse of the thickness of the material d{displaystyle d}

From this, it follows that the power of heat loss P{displaystyle P}

P=kAΔTd{displaystyle P={frac {kA,Delta T}{d}}}

Thermal conductivity depends on material, and, for fluids, its temperature and pressure. For comparison purposes, conductivity under standard conditions (20 °C at 1 atm) is commonly used. For some materials, thermal conductivity may also depend upon the direction of heat transfer.

The act of insulation is accomplished by encasing an object with material of low thermal conductivity in high thickness. Decreasing the exposed surface area could also lower heat transfer, but this quantity is usually fixed by the geometry of the object to be insulated.

Multi-layer insulation is used where radiative loss dominates, or when the user is restricted in volume and weight of the insulation (e.g. Emergency Blanket, radiant barrier)

Insulation of cylinders

Car exhausts usually require some form of heat barrier, especially high performance exhausts where a ceramic coating is often applied

For insulated cylinders, a critical radius must be reached. Before the critical radius is reached any added insulation increases heat transfer.[1] The convective thermal resistance is inversely proportional to the surface area and therefore the radius of the cylinder, while the thermal resistance of a cylindrical shell (the insulation layer) depends on the ratio between outside and inside radius, not on the radius itself. If the outside radius of a cylinder is increased by applying insulation, a fixed amount of conductive resistance (equal to 2*pi*k*L(Tin-Tout)/ln(Rout/Rin)) is added. However, at the same time, the convective resistance is reduced. This implies that adding insulation below a certain critical radius actually increases the heat transfer. For insulated cylinders, the critical radius is given by the equation[2]

- rcritical=kh{displaystyle {r_{critical}}={k over h}}

This equation shows that the critical radius depends only on the heat transfer coefficient and the thermal conductivity of the insulation. If the radius of the insulated cylinder is smaller than the critical radius for insulation, the addition of any amount of insulation will increase heat transfer.

Applications

Clothing and natural animal insulation in birds and mammals

Gases possess poor thermal conduction properties compared to liquids and solids, and thus makes a good insulation material if they can be trapped. In order to further augment the effectiveness of a gas (such as air) it may be disrupted into small cells which cannot effectively transfer heat by natural convection. Convection involves a larger bulk flow of gas driven by buoyancy and temperature differences, and it does not work well in small cells where there is little density difference to drive it, and the high surface-to-volume ratios of the small cells retards gas flow in them by means of viscous drag.

In order to accomplish small gas cell formation in man-made thermal insulation, glass and polymer materials can be used to trap air in a foam-like structure. This principle is used industrially in building and piping insulation such as (glass wool), cellulose, rock wool, polystyrene foam (styrofoam), urethane foam, vermiculite, perlite, and cork. Trapping air is also the principle in all highly insulating clothing materials such as wool, down feathers and fleece.

The air-trapping property is also the insulation principle employed by homeothermic animals to stay warm, for example down feathers, and insulating hair such as natural sheep's wool. In both cases the primary insulating material is air, and the polymer used for trapping the air is natural keratin protein.

Buildings

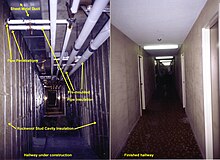

Common insulation applications in apartment building in Ontario, Canada.

Maintaining acceptable temperatures in buildings (by heating and cooling) uses a large proportion of global energy consumption. Building insulations also commonly use the principle of small trapped air-cells as explained above, e.g. fiberglass (specifically glass wool), cellulose, rock wool, polystyrene foam, urethane foam, vermiculite, perlite, cork, etc. For a period of time, Asbestos was also used, however, it caused health problems.

When well insulated, a building:

- is energy-efficient, thus saving the owner money.

- provides more uniform temperatures throughout the space. There is less temperature gradient both vertically (between ankle height and head height) and horizontally from exterior walls, ceilings and windows to the interior walls, thus producing a more comfortable occupant environment when outside temperatures are extremely cold or hot.

- has minimal recurring expense. Unlike heating and cooling equipment, insulation is permanent and does not require maintenance, upkeep, or adjustment.

- lowers the carbon footprint of a building.

Many forms of thermal insulation also reduce noise and vibration, both coming from the outside and from other rooms inside a building, thus producing a more comfortable environment.

Window insulation film can be applied in weatherization applications to reduce incoming thermal radiation in summer and loss in winter.

In industry, energy has to be expended to raise, lower, or maintain the temperature of objects or process fluids. If these are not insulated, this increases the energy requirements of a process, and therefore the cost and environmental impact.

Mechanical systems

Thermal insulation applied to exhaust component by means of plasma spraying

Space heating and cooling systems distribute heat throughout buildings by means of pipe or ductwork. Insulating these pipes using pipe insulation reduces energy into unoccupied rooms and prevents condensation from occurring on cold and chilled pipework.

Pipe insulation is also used on water supply pipework to help delay pipe freezing for an acceptable length of time.

Mechanical insulation is commonly installed in industrial and commercial facilities.

Refrigeration

A refrigerator consists of a heat pump and a thermally insulated compartment.[3]

Spacecraft

Thermal insulation on the Huygens probe

Cabin insulation of a Boeing 747-8 airliner

Launch and re-entry place severe mechanical stresses on spacecraft, so the strength of an insulator is critically important (as seen by the failure of insulating tiles on the Space Shuttle Columbia, which caused the shuttle airframe to overheat and break apart during reentry, killing the astronauts onboard). Re-entry through the atmosphere generates very high temperatures due to compression of the air at high speeds. Insulators must meet demanding physical properties beyond their thermal transfer retardant properties. Examples of insulation used on spacecraft include reinforced carbon-carbon composite nose cone and silica fiber tiles of the Space Shuttle. See also Insulative paint.

Automotive

Internal combustion engines produce a lot of heat during their combustion cycle. This can have a negative effect when it reaches various heat-sensitive components such as sensors, batteries and starter motors. As a result, thermal insulation is necessary to prevent the heat from the exhaust reaching these components.

High performance cars often use thermal insulation as a means to increase engine performance.

Factors influencing performance

Insulation performance is influenced by many factors, the most prominent of which include:

Thermal conductivity ("k" or "λ" value)- Surface emissivity ("ε" value)

- Insulation thickness

- Density

- Specific heat capacity

- Thermal bridging

It is important to note that the factors influencing performance may vary over time as material ages or environmental conditions change.

Calculating requirements

Industry standards are often rules of thumb, developed over many years, that offset many conflicting goals: what people will pay for, manufacturing cost, local climate, traditional building practices, and varying standards of comfort. Both heat transfer and layer analysis may be performed in large industrial applications, but in household situations (appliances and building insulation), air tightness is the key in reducing heat transfer due to air leakage (forced or natural convection). Once air tightness is achieved, it has often been sufficient to choose the thickness of the insulating layer based on rules of thumb. Diminishing returns are achieved with each successive doubling of the insulating layer.

It can be shown that for some systems, there is a minimum insulation thickness required for an improvement to be realized.[4]

See also

- Thermal mass

- List of thermal conductivities

- Insulative paint

References

^ "17.2 Combined Conduction and Convection". web.mit.edu. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Bergman, Lavine, Incropera and DeWitt, Introduction to Heat Transfer (sixth edition), Wiley, 2011.

^ Keep your fridge-freezer clean and ice-free. BBC. 30 April 2008

^ Frank P. Incropera; David P. De Witt (1990). Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 100–103. ISBN 0-471-51729-1.

Further reading

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

- US DOE publication, Residential Insulation

- US DOE publication, Energy Efficient Windows

- US EPA publication on home sealing

- DOE/CE 2002

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thermal insulation. |

- Thermal Performance: Understanding how reflective insulation works