阿司匹林

| |

| |

| 系统(IUPAC)命名名称 | |

|---|---|

2-Acetoxybenzoic acid | |

| 临床数据 | |

| 读音 | acetylsalicylic acid /əˌsiːtəlˌsælᵻˈsɪlᵻk/ |

| Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682878 |

| 医疗法规 |

|

| 妊娠分级 |

|

| 给药途径 | 通常为口服,也可以直肠给药。來欣阿斯匹林(lysine acetylsalicylate)則可经靜脈注射或肌肉注射 |

| 合法狀態 | |

| 合法状态 |

|

药代动力学数据 | |

| 生物利用度 | 80–100%[1] |

| 蛋白结合度 | 80–90%[2] |

| 代谢 | 肝脏(CYP2C19,也可能是CYP3A),也有部分在肠壁水解为水杨酸盐[2] |

| 生物半衰期 | 视药量而定;低剂量时为2-3小时(100 mg 以下時),高剂量时为15-30小时[2] |

| 排泄 | 尿液(80–100%)、汗、唾液、粪便[1] |

| 识别信息 | |

| CAS注册号 | 50-78-2 |

| ATC代码 | A01AD05 B01, N02 |

| PubChem | CID 2244 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 4139 |

| DrugBank | DB00945 |

| ChemSpider | 2157 |

| UNII | R16CO5Y76E |

| KEGG | D00109 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:15365 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL25 |

| 其他名称 | 邻-乙酰水杨酸 2-乙酰氧基苯甲酸 2-acetoxybenzoic acid acetylsalicylate acetylsalicylic acid O-acetylsalicylic acid |

PDB配体ID | AIN (PDBe, RCSB PDB) |

| 化学信息 | |

| 化学式 | C9H8O4 |

| 摩尔质量 | 180.158 g/mol[3] |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| 物理性质 | |

| 密度 | 1.40 g/cm3 |

| 熔点 | 136 °C(277 °F) [3] |

| 沸点 | 140 °C(284 °F) (分解) |

| 水溶液 | 3 mg/mL (20 °C) |

| (verify) | |

阿司匹林[注 1](英语:Aspirin),也称乙酰水杨酸(英语:acetylsalicylic acid),是水杨酸类药物,通常用作止痛剂、解热药和消炎药[4],亦能用於治療某些特定的發炎性疾病,例如川崎氏病、心包炎,以及風溼熱等等[4]。心肌梗塞後馬上給藥能降低死亡的風險[4]。本品也能防止血小板在血管破损处凝集,有抗凝作用。高心血管風險患者长期低剂量服用可预防心脏病、中风与血栓[4]。该药还可有效预防特定幾种癌症,特别是直肠癌。[5]。對於止痛及發燒而言,藥效一般會於30分鐘內發揮[4]。阿司匹林是一种非甾体抗炎药(NSAID),在抗發炎的角色上與其他NSAID類似,但阿斯匹靈還具有抗血小板凝集的效果[4]。

阿司匹林的其中一個常見的副作用是會引起胃部不適[4]。更嚴重的副作用則包含胃潰瘍、胃出血等等,也可能會使氣喘惡化[4]。其中年長者、酗酒者,以及還有服用其他非甾体抗炎药或抗凝剂者,出血風險更高[4],妊娠後期也不建議用藥[4]。有感染的孩童不建議用藥,因为这会增加患瑞氏综合征的风险。[4]。高劑量者可能會引起耳鸣[4]。

虽然它们都有名为水杨酸的类似结构,作用相似(解热、消炎、镇痛),抑制的环氧化酶(COX)也相同,但阿司匹林的不同之处在于其抑制作用不可逆,而且对环氧化酶-1(COX-1)的抑制作用比对环氧化酶-2的(COX-2)更强[6]。

阿司匹林衍生自柳树皮中发现的化学物质。早在2400年前柳树皮就用来治病,希波克拉底就用它来治头痛[7][8]。1763年,在牛津大学的沃德姆学院,爱德华·斯通首次从柳树皮中发现了阿司匹林的有效成分水杨酸[9]。1853年,化學家查爾斯·弗雷德里克·格哈特將水杨酸钠以乙酰氯處理,首次合成出乙醯水楊酸[10]。此後五十年,化學家們逐步提升生產的效率[10]:69–75。1897年,德国拜耳開始研究乙醯水楊酸的醫療用途,以代替高刺激性的水楊酸類藥物[10]:69–75。到1899年,拜耳以阿司匹林(Aspirin)為商標,將本品銷售至全球[11]。此後五十年,阿斯匹靈躍升成為使用最廣泛的藥物之一[12]。目前,拜耳公司在很多國家對於「阿司匹靈」一名的專利權已經過期,或是已經賣給其他公司[12]。

本品是当今世界上应用最广泛的药物之一,每年的消费量约40,000公噸(約500至1200億錠)[7][13]。本品列名於世界卫生组织基本药物标准清单之中,為基礎公衛體系必備藥物之一[14]。截至2014年 (2014-Missing required parameter 1=month!)[update],每劑在发展中国家的批發價約介於0.002至0.025美元之間[15]。截至2015年 (2015-Missing required parameter 1=month!)[update],每月劑量在美國的價格低於25.00美金[16]。本品目前屬於通用名药物[4]。

目录

1 医疗用途

1.1 疼痛

1.1.1 头痛

1.2 炎症与发热

1.3 心脏病和中风

1.4 术后

1.5 预防癌症

1.6 其他

2 不良反应

2.1 禁忌

2.2 胃肠道反应

2.3 对中枢神经系统的影响

2.4 瑞氏综合征

2.5 其他不良反应

2.6 过量服用

2.7 互相作用

2.8 耐药性

3 性质

3.1 多晶型性

4 制法

5 作用机理

5.1 对前列腺素和血栓素的抑制

5.2 对COX-1和COX-2的抑制

5.3 其他机理

6 药剂学

7 药代动力学

8 历史

8.1 商标

9 兽用

10 注

11 引用

12 延伸阅读

13 参见

14 外部链接

医疗用途

阿司匹林可以治疗多种疾病,包括发烧、疼痛、风湿热,也可治疗一些炎症,如类风湿性关节炎、心包炎和川崎病[17]。低剂量服用还可减少心肌梗死发作的死亡风险,某些情况下也可减少发生中风的风险[18][19][20]。部分证据表明阿司匹林可以预防直肠癌,但是其原理尚不明晰[21]。在美國,50歲至70歲的人且心血管疾病風險大於10%的族群可給予低劑量阿斯匹靈,且不會增加出血風險[22]。

疼痛

止痛用的阿司匹林,规格是325毫克(5格令)

无包衣的纯阿司匹林片,每片含大约90%的阿司匹林与一些惰性填料和粘合剂

对急性疼痛而言,阿司匹林是一种高效的镇痛药,但是通常认为其对疼痛的缓解效果不如布洛芬,因为阿司匹林更容易引发胃肠道出血[23]。 一般情况下,阿司匹林对肌肉抽搐、腹胀、胃扩张和急性皮肤刺激引起的疼痛无明显效果[24]。像其他非甾体抗炎药一样,阿司匹林与咖啡因一起使用的止痛效果比单独使用阿司匹林要好[25]。阿司匹林泡腾片,如白加黑或拜阿司匹林[26],比药片起效更快[27],可以有效治疗偏头痛[28]。可以有效地治疗某些形式的神经性疼痛[29]。

头痛

阿司匹林及其复方制剂都能有效治疗某几种头痛,但对另外几种则效果不明。因其他疾病或创伤导致的继发性头痛需要及时在医疗机构接受治疗。

国际头痛分类标准(ICHD)把原发性头痛分为紧张性头痛、偏头痛和丛集性头痛等类别。普遍[谁?]认为包括阿司匹林在内的非处方止痛药可以有效治疗紧张性头痛[30]。

阿司匹林,特别是和对乙酰氨基酚、咖啡因组成复方药物(如阿咖酚散),被认为是治疗偏头痛的首选,在疼痛刚发作时最有效,药效相当于服用低剂量的舒马曲坦[31]。

炎症与发热

阿司匹林可以不可逆地抑制环氧化酶(COX)来调节前列腺素系统,進而達到疼痛控制及退燒的效果[32]。也可以治疗某些急性或慢性的发炎性疾病[33],如类风湿性关节炎。[17]。阿司匹林是一种公认的成人用退烧药,但许多医学协会(包含美國家庭醫學會、美國兒科學會,以及美国食品药品监督管理局)及监管机构强烈反对用它治疗儿童发热,因为儿童在有病毒或细菌感染时使用水杨酸类药物可能会患上瑞氏综合征,患病几率虽小,但致死率很高[34][35][36]。鉴于这一风险,美国食品药品监督管理局(FDA)从1986年开始要求所有含阿司匹林的药物都需注明儿童和青少年不宜服用[37]。

心脏病和中风

1970年初,牛津大学心血管内科的名誉教授彼得·斯莱特研究了阿司匹林对心脏功能的影响和预防中风的效果。[38]斯莱特和他的团队为研究该药用于防治其他疾病打下基础。一份2015的报告指出,50岁的心脏病高危人群每日服用低剂量阿司匹林获益最大。[39]

阿斯匹靈在心肌梗死的治療上面扮演重要的角色[40]。一項臨床研究發現在懷疑有ST時段上升心肌梗塞(STEMI)的患者,阿斯匹靈能夠將30日死亡率從11.8%降低至9.4%[41]。在這些患者中,大出血的風險不會因為服藥增加,但小出血的風險會上升[41]。

阿司匹林能够预防部分人群罹患心脏病和中风,低剂量服用时能延缓心血管疾病的进程,降低有病史的人群的复发率(即“二次预防”)。[42][43]

不过阿司匹林对低风险人群(如没有心脏病和中风病史,没有基础性疾病的人)益处不大[44]。有些研究建议视情况服用,[45][46] 而另一些研究则认为出现其他状况(如胃肠道出血)的风险太大,得不偿失,所以完全不建议预防性的服用。[47]

预防性服用阿司匹林的另一问题是会产生耐药现象。[48][49] 如果患者有耐药性,药物的效力就会下降,这会增加中风的风险。[50] 有科学家建议对治疗方案进行测试,以确定哪些患者对阿司匹林和其他抗血栓药(如氯吡格雷)有耐药性。[51]

此外,也有建议含阿司匹林的复方制剂用于预防心血管疾病。[52][53]

术后

美国卫生保健研究和质量监督局(AHRQ)在一份指南中建议,完成冠状动脉再成形术(PCI),例如安装冠状动脉支架后,应终身服用阿司匹林。[54] 该药常与ADP受体拮抗剂(如氯吡格雷、普拉格雷、替格瑞洛等)联用以预防血栓,这种疗法叫做“双重抗血栓疗法”(DAPT)。美国和欧盟对术后采用这种疗法的时间和指征有着不同的指导方针。美国建议DAPT治疗至少持续12个月,而欧盟则建议根据不同情况持续治疗1至12个月不等。[55]

预防癌症

阿司匹林能降低癌症,[56] 特别是大肠癌(CRC)[21][57][58][59] 的发生率和死亡率。但效果需要服藥至少10至20年才能見到效果。[60]。此外,本品也能為為減少子宮內膜癌[61]、乳癌,以及前列腺癌[62]的風險。

一些人[谁?]认为,对患癌风险一般的人而言,若把阿司匹林的防癌作用和引起出血的风险相比,利大于弊,[56] 但还有人[谁?]不太确定是否如此。[63][64] 由于这种不确定性,美国预防服务工作组(USPSTF)在有关这个问题的指南中不建议患癌风险一般的人群服用阿司匹林预防大肠癌。[65]

其他

阿司匹林是治疗急性风湿热所引起的发热和关节痛的一线药物。这种疗法的疗程通常为一两星期,一般不会更长。发热和疼痛缓解后就不用再服药了,因为它不能减少心脏并发症和风湿性心脏瓣膜病后遗症的发生率。[66][67]萘普生的药效和阿司匹林相当,毒性更小,但由于临床使用经验有限,建议该药仅用作二线治疗。[66][68]

除了风湿热外,川崎病是少数几种可以让儿童服用阿司匹林的病症,[69] 不过并没有高质量的证据证实它的效果。[70]

低剂量的阿司匹林补充剂对妊娠毒血症有一定疗效。[71][72]

不良反应

禁忌

布洛芬或萘普生过敏的人群、[73][74]对水杨酸[75][76](或一般非甾体抗炎药)不耐受的人群禁用,患有哮喘的人群或会因非甾体抗炎药导致支气管痉挛的人群慎用。

因为阿司匹林会对胃壁产生影响,生产厂商建议患有消化性溃疡、轻症糖尿病或胃炎的人群在服用前先咨询医师。[73][77] 即使没有上述情况,当阿司匹林与酒精或华法林同时服用时也有导致胃出血的风险。[73][74] 患有血友病或其它出血性疾病的人群也不应服用该药及其它水杨酸类药物。[73][77] 患有遗传性疾病葡萄糖-6-磷酸脱氢酶缺乏症的人群服用阿司匹林会导致溶血性贫血,这取决于用量的多少和病情的严重性。[78] 不建议登革热患者服用该药,因为这会提高出血倾向。[79] 患有肾病、高尿酸血症或痛风的人群不宜服用,因为阿司匹林会抑制肾脏排出尿酸的功能,从而加重病情。另外不应使用该药治疗儿童或青少年的发热或流感,因为这与患上瑞氏综合征有关。[80]

胃肠道反应

阿司匹林会增加消化道出血的风险。[81] 尽管有些肠溶片在广告中宣称“不伤胃”,但研究表明肠溶片并未降低出血风险。[81] 若该药和其他非甾体抗炎药联用,出血风险还会增加。[81] 阿司匹林和氯吡格雷或华法林联用也会增加上消化道出血的风险。[82]

阿司匹林对COX-1的抑制似乎启动了胃的防御机制,使COX-2活性增强,[83] 若同时服用COX-2抑制剂,则会增加对胃黏膜的侵蚀。[84] 因此,当阿司匹林与任何“天然”的会抑制COX-2的补充剂(如大蒜提取物,姜黄素,越桔,松树皮,银杏,鱼油,白藜芦醇,染料木黄酮,槲皮素,间苯二酚等)联用时,必须特别小心。

除了肠溶片外,制药公司还会利用“缓冲剂”来缓解消化道出血的问题。缓冲剂旨在防止阿司匹林集結在胃壁上,不过它的效果存在争议。几乎所有抗酸药里的缓冲剂都能使用,如Bufferin使用氧化镁,还有制剂使用碳酸钙的。[85]

最近有对阿司匹林与维生素C联用以保护胃黏膜的研究。服用相同剂量的维生素C和阿司匹林与单独服用阿司匹林相比,能减少对胃的伤害。[86][87]

对中枢神经系统的影响

大鼠实验表明,阿司匹林的代谢物水杨酸在大剂量时能引起暂时性耳鸣,这是由于花生四烯酸的作用和NMDA受体级联反应。[88]

瑞氏综合征

瑞氏综合征是一种罕见的严重疾病,特征是急性脑病和脂肪肝,发生在少年儿童服用阿司匹林治疗发热或其他感染时。从1981年到1997年,美国疾病控制与预防中心接到1207宗未满18岁的瑞氏综合征病患报告。其中93%在综合征出现三周之前就已患病,主要是呼吸道感染、水痘和腹泻。81.9%的受检儿童都检出了水杨酸。[89] 出现阿司匹林引起瑞氏综合征的报告后,美国就采取了预防性的安全措施(如卫生局局长发出警告,更改含阿司匹林药品的标识),美国儿童的阿司匹林用量明显下降,瑞氏综合征的病例报告也明显减少。同样,英国发出儿童不宜服用阿司匹林的警告后,药物用量和病例报告也有减少。[89]美国食品药品监督管理局现在建议12岁以下儿童发热都不能服用阿司匹林或含有阿司匹林的药物。[80] 英国药品和医疗产品监管署也建议16岁以下儿童不应服用阿司匹林,除非另有医嘱。[90]

其他不良反应

小部分人服用阿司匹林后会产生类似于过敏的反应,如荨麻疹、水肿和头痛。这种反应是由于水杨酸不耐受,并不是真正的过敏,而是连一点点水杨酸都无法代谢所导致的药物过量。

有些人服用阿司匹林会产生皮肤组织水肿,有研究发现有些病患服药1到6小时后就会发生。不过,阿司匹林单独服用并不会导致水肿,和非甾体抗炎药联用时才会发生。[91]

阿司匹林会增加脑部微出血的风险,磁共振成像(MRI)可见5至10毫米的斑块,或者是更小的低信号斑块。[92][93]

一项研究估计每天平均服用270毫克的阿司匹林后,脑出血(ICH)的概率绝对值增加了万分之12,[94] 与此相比,心肌梗死的概率绝对值下降了万分之137,缺血性中风的概率绝对值则下降了万分之39。[94] 如果已经发生脑出血,阿司匹林会提高死亡率,每天大约250毫克的剂量导致发病后三个月内死亡的概率是原来的2.5倍(95%置信区间是1.3倍到4.6倍)[95]。

阿司匹林和其他非甾体抗炎药会抑制前列腺素合成,引起低肾素性低醛固酮症,可能引发高血钾症。不过,当肾功能和血容量都正常时,这些药物并不会导致高血钾症。[96]

阿司匹林在术后十天内都能引起长时间出血。一项研究选择了6499名手术病人进行观察,发现其中有30人需要再次进行手术以控制出血。这30人中有20人是弥漫性出血,另外10人只有一个部位出血。弥漫性出血是由术前单独使用阿司匹林或和其他非甾体抗炎药联用引起的,而离散的出血则不是。[97]

2015年7月9日,美国食品药品监督管理局提升了对非甾体抗炎药增加心脏病和中风风险的警告。阿司匹林虽然也是非甾体抗炎药,但并不在警告的范围内。[98]

| 情况 | 凝血酶原时间 | 部分凝血活酶时间 | 出血时间 | 血小板计数 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

维生素K缺乏症或华法林 | 延长 | 正常或轻度延长 | 无影响 | 无影响 |

弥散性血管内凝血 | 延长 | 延长 | 延长 | 减少 |

血管性血友病 | 无影响 | 延长或无影响 | 延长 | 无影响 |

血友病 | 无影响 | 延长 | 无影响 | 无影响 |

阿司匹林 | 无影响 | 无影响 | 延长 | 无影响 |

血小板减少症 | 无影响 | 无影响 | 延长 | 减少 |

肝功能衰竭,早期 | 延长 | 无影响 | 无影响 | 无影响 |

| 肝功能衰竭, 末期 | 延长 | 延长 | 延长 | 减少 |

尿毒症 | 无影响 | 无影响 | 延长 | 无影响 |

先天性无纤维蛋白原血症 | 延长 | 延长 | 延长 | 无影响 |

凝血因子V缺乏 | 延长 | 延长 | 无影响 | 无影响 |

凝血因子X缺乏并可见淀粉样蛋白减少性紫癜 | 延长 | 延长 | 无影响 | 无影响 |

血小板无力症 | 无影响 | 无影响 | 延长 | 无影响 |

巨大血小板綜合症 | 无影响 | 无影响 | 延长 | 减少或无影响 |

凝血因子XII缺乏症 | 无影响 | 延长 | 无影响 | 无影响 |

C1INH缺乏症 | 无影响 | 缩短 | 无影响 | 无影响 |

过量服用

阿司匹林过量分为急性和慢性。急性过量是指一次性服用大剂量的药物,而慢性过量则是指一段时间内服用超过正常剂量的药物。急性过量的死亡率是2%。慢性过量的死亡率更高達25%,[99]且对儿童影响尤为严重。[100] 中毒的治疗方法有使用活性炭、静脉注射葡萄糖和生理盐水,使用碳酸氢钠,还有透析。[101] 通常用自动分光光度法测量血浆中阿司匹林的活性代谢产物,即水杨酸来诊断中毒。一般来说,正常服药治疗后血浆中水杨酸含量为30-100毫克每升,高剂量服用的患者血浆中的含量为50-300毫克每升,急性中毒患者血浆中的含量为700-1400毫克每升。服用次水杨酸铋、水杨酸甲酯和水杨酸钠后也会产生水杨酸。[102][103]

互相作用

阿司匹林和其他藥物會发生互相作用,如乙酰唑胺和氯化铵会增加水杨酸的毒性,酒精则会增加该药导致胃肠道出血的风险[73][74] 血液中阿司匹林还会影响部分药物与蛋白质结合,包括抗糖尿病药(甲苯磺丁脲和氯磺丙脲)、华法林、氨甲蝶呤、苯妥英、丙磺舒、丙戊酸(会影响该药代谢中的重要一环β-氧化)和其他非甾体抗炎药。另外皮质类固醇能降低阿司匹林的浓度,布洛芬会抵消阿司匹林的抗血栓作用,影响其保护心血管和预防中风的功能。[104] 阿司匹林会降低安体舒通的药理活性,经由肾小管分泌时还会与青霉素G竞争。[105] 阿司匹林也会抑制维生素C的吸收。[106][107][108]

耐药性

在有些人身上,阿司匹林的抗血栓作用不如别的人明显,这种现象称为阿司匹林耐药性或是对阿司匹林不敏感。研究表明女性比男性更易产生耐药性,[109] 另一项研究总共调查了2930人,发现有28%的人有耐药性。[110] 不过还有一项针对100名意大利人的研究表明,虽然看上去有31%的人耐药,不过只有5%的人是真正耐药的,其他人只是没按要求服药而已。[111] 另一项研究在400名健康志愿者中没有发现真正对阿司匹林有抗药性的人,但有服用肠溶阿司匹林的人出现“伪耐药性,体现为药物吸收的延迟和减少”。[112]

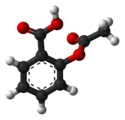

性质

阿司匹林是一种白色晶体,熔点136 °C(277 °F),在140 °C(284 °F)时分解[113]。

阿司匹林是水杨酸的乙酰衍生物,呈弱酸性,在25 °C(77 °F)下酸度系数为3.5。[114] 阿司匹林可以在醋酸铵或碱金属的醋酸盐、碳酸盐、柠檬酸盐和氢氧化物溶液中迅速分解。阿司匹林在干燥空气中性质稳定,但在潮湿的环境中会逐渐水解成乙酸和水杨酸。在碱性溶液中,阿司匹林迅速水解,生成只含有水杨酸盐与乙酸盐的澄清溶液。[115]

如同面粉厂一样,生产阿司匹林的工厂也需要留意空气中阿司匹林的含量,因为过量的粉末会导致粉尘爆炸。在美国,美国国家职业安全卫生研究所(NIOSH)将建议暴露限值定为5毫克每立方米(时间加权平均)。[116]1989年,美国职业安全与健康管理局(OSHA)将允许最大暴露限值定为5毫克每立方米,但这项规定在1993年OSHA和美国劳工联合会-产业工会联合会(AFL–CIO)的诉讼中被废除。 [117]

多晶型性

多晶型性是同一种物质形成多种晶体结构的能力,它对药物成分的开发至关重要。很多药物只有一种晶体结构经过监管部门批准。有很长一段时间,人们只知道阿司匹林的一种晶体结构,从1960年起开始怀疑它还有一种晶体结构,2005年才发现了这种神秘的结构。[118] 邦德等人测定了这种结构的细节。[119] 这种新的晶体结构是在热乙腈中使阿司匹林和左乙拉西坦共同结晶时发现的。[118]

制法

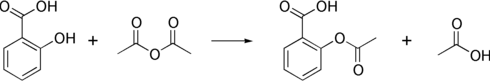

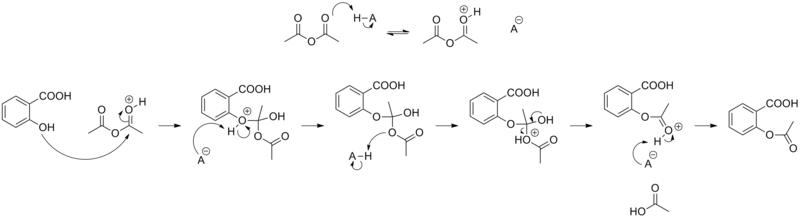

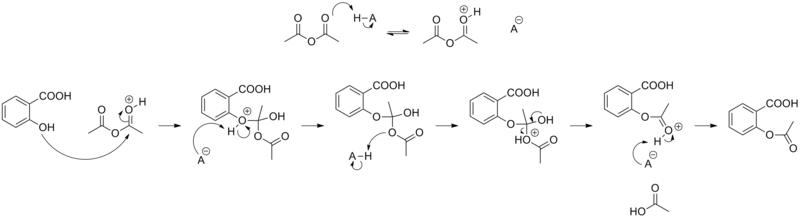

制取阿司匹林的反应通常归为酯化反应。水杨酸和乙酸酐(一种乙酸的衍生物)发生反应,水杨酸中的羟基替换为酯基(R-OH → R-OCOCH3),生成阿司匹林和副产物乙酸。通常用少量硫酸作催化剂(有时用磷酸)。[120]

- 反应机理

含高浓度阿司匹林的制剂常有醋味,[121]这是因为阿司匹林会在潮湿的环境下发生水解,分子分解成水杨酸和乙酸。[122]

作用机理

1971年,英国皇家外科学院的药理学家约翰·范恩证实了阿司匹林会抑制前列腺素和血栓素的生成[123][124] 他因这项发现和苏恩·伯格斯特龙、本格特·萨米尔松共同获得1982年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。[125] 1984年获授下级勋位爵士。[126]

对前列腺素和血栓素的抑制

阿司匹林能抑制前列腺素和血栓素是因为该药能不可逆地使合成前列腺素和血栓素所需的环氧合酶(COX,学名叫前列腺素氧化环化酶,PTGS)失活。阿司匹林能使PTGS活性位点中的一个丝氨酸残基乙酰化,这是它和其他非甾体抗炎药(如双氯芬酸钠和布洛芬)的不同之处,因为其他的药抑制作用都是可逆的[127][128]。

阿司匹林低剂量服用时能阻止血小板中血栓素A2的合成,这会在受影响的血小板的生命周期(约8–9天)内抑制血小板聚集。阿司匹林的这种抗血栓作用可用于降低心脏病发生率。[129] 每天服用40 mg的阿司匹林能显著抑制血栓素A2的最大急性合成量,但不影响前列腺素I2的合成,不过服用剂量更高时就会抑制前列腺素I2的合成。[130]

前列腺素是身体局部产生的一种激素,它有多种作用,包括在下丘脑中调节体温[131]

,将痛觉传递到大脑,还会引起炎症[132][133]。血栓素会使血小板聚集形成血栓,而心肌梗死主要是由血栓导致的,因此低剂量服用阿司匹林能有效防止心肌梗死[134]。

对COX-1和COX-2的抑制

阿司匹林可以抑制环氧化酶-1(COX-1)和环氧化酶-2(COX-2)。它能不可逆地抑制COX-1并且改变COX-2的酶活性。COX-2通常产生的大多是会促进发炎的前列腺素类激素,但受阿司匹林作用后则产生能抗炎的脂氧素。新一代非甾体抗炎药——昔布类COX-2抑制剂——可以单独抑制COX-2,以减少对胃肠道的副作用。[135][136]

然而许多新一代的COX-2抑制剂如罗非昔布在过去十年内都遭到了撤回,因为有证据表明它们会增加患心脏病和中风的风险。人体的血管内皮细胞原本会合成COX-2。选择性抑制COX-2后,因为血小板里的COX-1未受影响,前列腺素(尤其是前列环素PGI2)的合成相比血栓素会有所降低。这样PGI2抗凝血的保护作用就消失了,这会增加血栓、心肌梗死和其他相关的循环系统疾病的风险。因为血小板没有DNA,它的COX-1若被阿司匹林不可逆地抑制,就无法再生,这是和昔布类可逆抑制剂的不同之处。[137][138]

此外,阿斯匹靈除了有抑制COX-2的環氧化能力之外,還能將其轉化為類似脂加氧酶的酵素。被阿斯匹靈處理過後的COX-2可以將多種多元不飽和脂肪酸轉為過氧化物,這些過氧化物又會被代謝為具有抗發炎活性的特異性促修復介質,如脂氧素、消散素、巨噬細胞消炎介質等等。[139][140][141]

其他机理

阿司匹林还有三种作用方式。一是使线粒体的氧化磷酸化解偶联。阿司匹林会携带质子从线粒体膜间隙扩散进入线粒体基质,然后再次电离释放质子。简而言之,阿司匹林作为缓冲剂运输质子,因此高剂量服用时会因电子传递链释放的热量而造成发热,这和低剂量服用的退烧作用相反。[142] 二是阿司匹林会促进一氧化氮自由基的生成。一氧化氮自由基本身在小鼠体内也有抗炎的作用,它能减少白细胞粘附,后者是免疫系统应对感染的重要一步。不过,没有足够证据表明阿司匹林能抗感染。[143] 第三,更新的研究表明水杨酸及其衍生物能通过NF-κB调节细胞信号。NF-κB是一种转录因子复合体,在许多生物过程(包括发炎)中起重要作用。[144]

阿司匹林在体内分解为水杨酸,而水杨酸本身则有抗炎、退烧、镇痛等作用。2012年发现水杨酸还能激活AMP活化蛋白激酶,这是水杨酸和阿司匹林药效的一种可能的解释。[145][146] 阿司匹林分子中的乙酰基也并非没有作用。细胞蛋白的乙酰化是其轉譯後修飾中被广泛研究的现象。阿司匹林能使包括COX同工酶在内的几种蛋白质乙酰化。这些乙酰化反应可能可以阐释一些阿司匹林尚未得到解释的效应[147][148]。

药剂学

规格为5格令(325毫克)的阿司匹林包衣片

5格令的阿司匹林,药瓶上的使用说明里写剂量是“325 mg (5 gr)”

一般来说,成人用于治疗发烧或关节炎时每天服用四次,[134] 这和以前治疗风湿热时所用的剂量接近。[149] 有或怀疑有冠状动脉病史的人要预防心肌梗死(MI),每天低剂量服用一次即可。[134]

USPSTF在2009年3月向45-79岁的男性和55-79岁的女性建议,如果阿司匹林降低男性心肌梗死和女性中风的风险所带来的潜在效益要大于引起消化道出血的潜在危害,那么就提倡服用该药以预防冠状动脉心脏疾病。[150] WHI的研究表明女性如果坚持低剂量(75毫克或81毫克)服用,死于心血管疾病的风险就会降低25%,总死亡率降低14%。[150] 低剂量服用阿司匹林(每天75毫克或81毫克)也和心血管疾病发病率降低有关,长期服用以预防疾病的患者利用这种方式可以兼顾药物的有效性和安全性。[150]

儿童服用阿司匹林治疗川崎病时,服用剂量和体重相关,头两周每天服用四次,接下来六至八周降低剂量,每天服用一次。[151]

药代动力学

乙酰水杨酸是一种弱酸,口服后在胃的酸性环境中几乎不电离,而是迅速经细胞膜吸收。小肠中较高的pH促进了药物的电离,从而减缓了药物在小肠中的吸收。过量服用时药物会凝结,所以吸收更慢,血浆浓度在服用后24小时内都会上升。[152][153][154]

血液中的水杨酸有50–80%与白蛋白结合,其余是具有活性的电离态。药物和蛋白质的结合和浓度有关。结合位点饱和以后游离态的水杨酸就会增加,其毒性也会增强。药物的分布体积是0.1–0.2升每千克。酸中毒会增强水杨酸向组织中的渗透,从而增加药物的分布体积。[154]

若按治疗剂量服用,则有多达80%的水杨酸在肝脏中代谢。它和甘氨酸反应生成水杨酰胺乙酸,但这种代谢途径容量有限。少量水杨酸也会羟基化形成龙胆酸。大剂量服用时,药物代谢从一级反应变为零级反应,因为代谢途径已饱和,肾脏的排出变得更加重要。[154]

水杨酸主要通过肾脏作为水杨酰胺乙酸(75%)、游离水杨酸(10%)、水杨酸苯酚(10%)、酰基葡萄糖醛酸苷(5%)、龙胆酸(< 1%)、2,3-二羟基苯甲酸排泄。[155]当摄入低剂量时(小于250mg,成人),所有途径都通过一级动力学,消除半衰期约为2.0至4.5小时。[156][157] 当摄入高剂量水杨酸时(大于4000mg),半衰期会延长至15-30小时,[158]因为水杨酰胺乙酸和水杨酚醛葡糖苷酸的生物转化途径已饱和。[159] 代谢途径的饱和使得肾脏对水杨酸的排泄更加重要,而尿液酸碱度对其影响也更为敏感。当尿液的pH值从5升至8时,肾脏对水杨酸的清除能力会提升10-20倍。通过碱化尿液来增加水杨酸的清除率便是利用了这一点。[160]

历史

1923年的阿司匹林广告

自古以来,人们就知道含有活性成分水杨酸的植物提取物(如柳树皮和绣线菊属植物)能够镇痛、退烧。希波克拉底(约前460年–前377年)留下的历史记录就描述了柳树的树皮和树叶磨成的粉能够缓解以上症状。[161]

1763年英国牧师爱德华·斯通在牛津发现阿司匹林的活性成分水杨酸。法国化学家查尔斯·弗雷德里克·格哈特首先于1853年合成了乙酰水杨酸。他在制取和研究各种酸酐的性质时,把乙酰氯和水杨酸钠混合,二者发生剧烈反应,熔化后又很快凝固了。因为当时还没有分子结构理论,格哈特把所得的化合物称为“水杨酸乙酸酐”(wasserfreie Salicylsäure-Essigsäure)。他为撰写关于酸酐的论文进行了很多反应,这个制备阿司匹林的反应只是其中之一,后来他也没有进一步研究。[162]

阿司匹林、海洛因、赖塞托和醋氨沙洛的广告

六年之后的1859年,冯·基尔姆让水杨酸和乙酰氯反应,制得了分析纯的乙酰水杨酸,他称之为“乙酰化水杨酸”( acetylierte Salicylsäure)[163] 1869年,施罗德、普林兹霍恩和克劳特重复了格哈特(利用水杨酸钠)的和基尔姆(利用水杨酸)的合成方式,结果证实两个反应产物相同——乙酰水杨酸。他们第一次确定了产物的正确结构——乙酰基和酚基上的氧相连。[164]

1897年拜耳公司的化学家把旋果蚊子草(Filipendula ulmaria)合成的水杨苷经过修饰后合成了一种药物,它比纯净的水杨酸对消化道刺激更小。这个项目由哪个化学家领衔存在争议。拜耳说合成是由费利克斯·霍夫曼完成的,但后来犹太化学家阿瑟·艾兴格林声称他才是首席研究员,而他的贡献记录被纳粹政权抹去了。[165][166]这种药学名叫乙酰水杨酸,拜耳公司把它称为阿司匹林(Aspirin),这来自于旋果蚊子草的植物名(拉丁語:Filipendula ulmaria)。[167] 到了1899年,拜耳已在全球市场销售此药。[168] 二十世纪上半叶,阿司匹林越来越受欢迎,这是因为人们认为它在1918年流感大流行中发挥了作用。然而最近的研究却显示,它也是流感致死率高的部分原因,不过这种说法颇受争议,未被广泛认可。[169] 阿司匹林带来的丰厚利润使药厂激烈竞争,该药的各种品牌和产品像雨后春笋般冒了出来,在1917年拜耳公司的美国专利过期了以后更是如此。[170][171]

对乙酰氨基酚和布洛芬于1956年和1959年相继问世以后,阿司匹林的使用率开始下降。[172]60和70年代,约翰·范恩等人发现了阿司匹林的作用机理,60至80年代的其他研究和临床试验证明该药有抗凝血的药效,可降低血栓疾病的发病率。[173] 由于广泛用于预防心脏病和中风,阿司匹林的销量从20世纪末开始复苏,21世纪以来持续向好。[174]

商标

德国在一战中投降后,1919年各国签订的凡尔赛条约中战后赔偿的部分规定阿司匹林(Aspirin)连同海洛因在法国、俄罗斯、英国和美国不再是注册商标,而成为了通用名称。[175][176][177] 现在aspirin(a小写)在澳大利亚、法国、印度、爱尔兰、新西兰、巴基斯坦、牙买加、哥伦比亚、菲律宾、南非、英国和美国是通用名称,而Aspirin(a大写)在德国、加拿大、墨西哥等80多个国家还是拜耳公司的注册商标。公司在所有市场上出售的药物成分都是乙酰水杨酸,但包装和物理性质则在各个市场都不相同。[178][179]

兽用

兽医有时用阿司匹林来镇痛或抗血栓,主要给狗用,有时给马用,不过现在一般会用副作用较少的新疗法[180]。

狗和马都会出现水杨酸产生的胃肠道副作用,不过阿司匹林可以用来治疗老年狗的关节炎,也有治疗马的蹄叶炎的可能。[181][182] 不过现在该药已很少用于治疗蹄叶炎,因为可能适得其反。阿司匹林应该只在兽医的直接指导下使用,特别是猫,因其缺乏有助于药物排出的葡萄糖醛酸,用药比较危险。[183] 连续4周每48小时给猫服用25毫克/千克体重的阿司匹林并不产生临床中毒症状。[184] 推荐用于猫的解热镇痛剂量是每48小时10毫克/千克体重。[185]

注

^ 或译作阿司匹灵、阿斯匹灵、阿士匹灵

引用

^ 1.01.1 Zorprin, Bayer Buffered Aspirin (aspirin) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more. Medscape Reference. WebMD. [3 April 2014]. (原始内容存档于7 April 2014). 已忽略未知参数|df=(帮助)

^ 2.02.12.2 Brayfield, A (编). Aspirin. Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. Pharmaceutical Press. 14 January 2014 [3 April 2014].

^ 3.03.1 Haynes, William M. (编). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics 92nd. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. 2011: 3.8. ISBN 1439855110.

^ 4.004.014.024.034.044.054.064.074.084.094.104.114.12 Aspirin. Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. June 6, 2016 [30 August 2016]. (原始内容存档于25 April 2017). 已忽略未知参数|df=(帮助)

^ Patrignani, P; Patrono, C. Aspirin and Cancer.. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 30 August 2016, 68 (9): 967–76. PMID 27561771. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.083.

^ Burke, Anne; Smyth, Emer; FitzGerald, Garret A. 26: Analgesic Antipyretic and Antiinflammatory Agents. (编) Brunton, Laurence L.; Lazo, John S.; Parker, Keith. Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics 11. New York: McGraw-Hill. 2006: 671–716. ISBN 978-0-07-142280-2.

^ 7.07.1 Jones, Alan. Chemistry: An Introduction for Medical and Health Sciences. John Wiley & Sons. 2015: 5–6. ISBN 9780470092903 (英语).

^ Ravina, Enrique. The Evolution of Drug Discovery: From Traditional Medicines to Modern Drugs. John Wiley & Sons. 2011: 24. ISBN 9783527326693 (英语).

^ Stone Edmund. An Account of the Success of the Bark of the Willow in the Cure of Agues. In a Letter to the Right Honourable George Earl of Macclesfield, President of R. S. from the Rev. Mr. Edmund Stone, of Chipping-Norton in Oxfordshire. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 1763, 53: 195–200. JSTOR 105721. doi:10.1098/rstl.1763.0033.

^ 10.010.110.2 Jeffreys, Diarmuid. Aspirin the remarkable story of a wonder drug.. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. 2008. ISBN 9781596918160. (原始内容存档于8 September 2017). :46–48

^ Mann, Charles C.; Plummer, Mark L. The aspirin wars : money, medicine, and 100 years of rampant competition 1st. New York: Knopf. 1991: 27. ISBN 0-394-57894-5.

^ 12.012.1 Aspirin. Chemical & Engineering News. [2007-08-13].

^ Warner, T D; Warner TD, Mitchell JA. Cyclooxygenase-3 (COX-3): filling in the gaps toward a COX continuum?. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002, 99 (21): 13371–3. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9913371W. PMC 129677. PMID 12374850. doi:10.1073/pnas.222543099.

^ WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List) (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015 [8 December 2016]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于13 December 2016).

^ Acetylsalicylic Acid. International Drug Price Indicator Guide. [30 August 2016].

^ Hamilton, Richart. Tarascon pocket pharmacopoeia 2015 deluxe lab-coat. Jones & Bartlett Learning. 2015: 5. ISBN 9781284057560.

^ 17.017.1 Aspirin. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. [3 April 2011]. (原始内容存档于1 January 2011).

^ Aspirin for reducing your risk of heart attack and stroke: know the facts. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. [26 July 2012]. (原始内容存档于14 August 2012). 已忽略未知参数|df=(帮助)

^ Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. [26 July 2012]. (原始内容存档于11 July 2012). 已忽略未知参数|df=(帮助)

^ Seshasai, SR; Wijesuriya, S; Sivakumaran, R; Nethercott, S; Erqou, S; Sattar, N; Ray, KK. Effect of aspirin on vascular and nonvascular outcomes: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Archives of Internal Medicine. 13 February 2012, 172 (3): 209–16. PMID 22231610. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.628.

^ 21.021.1 Algra, AM; Rothwell, PM. Effects of regular aspirin on long-term cancer incidence and metastasis: a systematic comparison of evidence from observational studies versus randomised trials. The Lancet Oncology. May 2012, 13 (5): 518–27. PMID 22440112. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70112-2.

^ Bibbins-Domingo, K; U.S. Preventive Services Task, Force. Aspirin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 21 June 2016, 164 (12): 836–45. PMID 27064677. doi:10.7326/m16-0577.

^ Sachs, CJ. Oral analgesics for acute nonspecific pain. American Family Physician. 2005, 71 (5): 913–918. PMID 15768621. (原始内容存档于28 May 2014). 已忽略未知参数|df=(帮助)

^ Gaciong. The real dimension of analgesic activity of aspirin. Thrombosis Research. 2003, 110 (5–6): 361–364. PMID 14592563. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2003.08.009.

^ Derry, CJ; Derry, S; Moore, RA. Derry, Sheena, 编. Caffeine as an analgesic adjuvant for acute pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012, 3 (3): CD009281. PMID 22419343. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009281.pub2.

^ Blowfish (aspirin, caffeine) tablet, effervescent [Rally Labs LLC]. DailyMed. U.S. Federal Drug Administration. [27 July 2012]. (原始内容存档于28 February 2013). 已忽略未知参数|df=(帮助)

^ Hersh, E; Moore, P; Ross, G. Over-the-counter analgesics and antipyretics: A critical assessment. Clinical Therapeutics. 2000, 22 (5): 500–548. PMID 10868553. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(00)80043-0.

^ Mett, A; Tfelt-Hansen, P. Acute migraine therapy: recent evidence from randomized comparative trials. Current Opinion in Neurology. 2008, 21 (3): 331–337. PMID 18451718. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e3282fee843.

^ Kingery, WS. A critical review of controlled clinical trials for peripheral neuropathic pain and complex regional pain syndromes. Pain. November 1997, 73 (2): 123–39. PMID 9415498. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00049-3.

^ Loder, E; Rizzoli, P. Tension-type headache. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 12 January 2008, 336 (7635): 88–92. PMC 2190284. PMID 18187725. doi:10.1136/bmj.39412.705868.AD.

^ Gilmore, B; Michael, M. Treatment of acute migraine headache. American family physician. 2011-02-01, 83 (3): 271–80. PMID 21302868.

^ Bartfai, T; Conti, B. Fever. The Scientific World Journal. 16 March 2010, 10: 490–503. PMC 2850202. PMID 20305990. doi:10.1100/tsw.2010.50.

^ Thea Morris, Melanie Stables, Adrian Hobbs, Patricia de Souza, Paul Colville-Nash, Tim Warner, Justine Newson, Geoffrey Bellingan, and Derek W. Gilroy. Effects of low-dose aspirin on acute inflammatory responses in humans. Journal of Immunology. 1 August 2009, 183 (3): 2089–2096. PMID 19597002. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0900477.

^ Pugliese, A; Beltramo, T; Torre, D. Reye's and Reye's-like syndromes. Cell biochemistry and function. October 2008, 26 (7): 741–6. PMID 18711704. doi:10.1002/cbf.1465.

^ Beutler, AI; Chesnut, GT; Mattingly, JC; Jamieson, B. FPIN's Clinical Inquiries. Aspirin use in children for fever or viral syndromes. American Family Physician. 15 December 2009, 80 (12): 1472. PMID 20000310.

^ Medications Used to Treat Fever. American Academy of Pediatrics. [25 November 2012]. (原始内容存档于18 February 2013).

^ 51 FR 8180 (PDF). United States Federal Register. 7 March 1986, 51 (45) [25 November 2012]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于19 August 2011).

^ Research Confirms and Points to Future Aspirin Uses For Disease Prevention – re> BERLIN, Dec. 1 /PRNewswire/. Prnewswire.com. [2014-05-05].

^ People in Their 50s Benefit Most From Low-Dose Aspirin, Report Says. [2015-09-24].

^ Myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation: the acute management of myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation [Internet]. NICE Clinical Guidelines. July 2013, (167). 17.2 Asprin. PMID 25340241. (原始内容存档于31 December 2015).

^ 41.041.1 Quaas, Joshua. Aspirin given immediately for a major heart attack (STEMI). The NNT. November 28, 2009 [10 August 2016]. (原始内容存档于9 August 2016).

^ Hall, SL; Lorenc, T. Secondary prevention of coronary artery disease. American family physician. 2010-02-01, 81 (3): 289–96. PMID 20112887.

^ Baigent, C; Blackwell, L; Collins, R; Emberson, J; Godwin, J; Peto, R; Buring, J; Hennekens, C; Kearney, P; Meade, T; Patrono, C; Roncaglioni, MC; Zanchetti, A. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009, 373 (9678): 1849–60. PMC 2715005. PMID 19482214. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60503-1.

^ Richman, IB; Owens, DK. Aspirin for Primary Prevention. The Medical Clinics of North America (Review). July 2017, 101 (4): 713-24. PMID 28577622. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2017.03.004.

^ Wolff, T; Miller, T; Ko, S. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: an update of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009-03-17, 150 (6): 405–10. PMID 19293073. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-150-6-200903170-00009.

^ U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Recommendation Statement. [2012-08-15].

^ Berger, JS; Lala, A, Krantz, MJ, Baker, GS, Hiatt, WR. Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular events in patients without clinical cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. American heart journal. July 2011, 162 (1): 115–24.e2. PMID 21742097. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2011.04.006.

^ Wang, TH; Bhatt, DL; Topol, EJ. Aspirin and clopidogrel resistance: an emerging clinical entity. European heart journal. March 2006, 27 (6): 647–54. PMID 16364973. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehi684.

^ Oliveira, DC; Silva, RF; Silva, DJ; Lima, VC. Aspirin resistance: fact or fiction?. Arquivos brasileiros de cardiologia. September 2010, 95 (3): e91–4. PMID 20944898. doi:10.1590/S0066-782X2010001300024.

^ Topçuoglu, MA; Arsava, EM; Ay, H. Antiplatelet resistance in stroke. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. February 2011, 11 (2): 251–63. PMC 3086673. PMID 21306212. doi:10.1586/ern.10.203.

^ Ben-Dor, I; Kleiman, NS; Lev, E. Assessment, mechanisms, and clinical implication of variability in platelet response to aspirin and clopidogrel therapy. The American journal of cardiology. 2009-07-15, 104 (2): 227–33. PMID 19576352. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.03.022.

^ Norris, JW. Antiplatelet agents in secondary prevention of stroke: a perspective. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. September 2005, 36 (9): 2034–6. PMID 16100022. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000177887.14339.46.

^ Sleight, P; Pouleur, H; Zannad, F. Benefits, challenges, and registerability of the polypill. European heart journal. July 2006, 27 (14): 1651–6. PMID 16603580. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehi841.

^ National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC). 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary artery intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions.. United States Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). [2012-08-28]. (原始内容存档于2012-08-13).

^ Musumeci, G; Di Lorenzo, E; Valgimigli, M. Dual antiplatelet therapy duration: what are the drivers?. Current Opinion in Cardiology. December 2011,. 26 Suppl 1: S4–14. PMID 22129582. doi:10.1097/01.hco.0000409959.11246.ba.

^ 56.056.1 Cuzick, J; Thorat, MA; Bosetti, C; Brown, PH; Burn, J; Cook, NR; Ford, LG; Jacobs, EJ; Jankowski, JA; La Vecchia, C; Law, M; Meyskens, F; Rothwell, PM; Senn, HJ; Umar, A. Estimates of benefits and harms of prophylactic use of aspirin in the general population.. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2014-08-05, 26: 47–57. PMID 25096604. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdu225.

^ Manzano, A; Pérez-Segura, P. Colorectal cancer chemoprevention: is this the future of colorectal cancer prevention?. TheScientificWorldJournal. 2012, 2012: 327341. PMC 3353298. PMID 22649288. doi:10.1100/2012/327341.

^ Chan, AT; Arber, N; Burn, J; Chia, WK; Elwood, P; Hull, MA; Logan, RF; Rothwell, PM; Schrör, K; Baron, JA. Aspirin in the chemoprevention of colorectal neoplasia: an overview. Cancer prevention research (Philadelphia, Pa.). February 2012, 5 (2): 164–78. PMC 3273592. PMID 22084361. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0391.

^ Thun, MJ; Jacobs, EJ; Patrono, C. The role of aspirin in cancer prevention. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2012-04-03, 9 (5): 259–67. PMID 22473097. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.199.

^ Richman, IB; Owens, DK. Aspirin for Primary Prevention. The Medical Clinics of North America (Review). July 2017, 101 (4): 713-24. PMID 28577622. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2017.03.004.

^ Verdoodt, Freija; Friis, Søren; Dehlendorff, Christian; Albieri, Vanna; Kjaer, Susanne K. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and risk of endometrial cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Gynecologic Oncology: 352–358. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.12.009.

^ Bosetti, C; Rosato, V; Gallus, S; Cuzick, J; La Vecchia, C. Aspirin and cancer risk: a quantitative review to 2011. Annals of Oncology. 19 April 2012, 23 (6): 1403–1415. PMID 22517822. doi:10.1093/annonc/mds113.

^ Sutcliffe, P; Connock, M; Gurung, T; Freeman, K; Johnson, S; Kandala, NB; Grove, A; Gurung, B; Morrow, S; Clarke, A. Aspirin for prophylactic use in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer: a systematic review and overview of reviews.. Health technology assessment (Winchester, England). Sep 2013, 17 (43): 1–253. PMID 24074752. doi:10.3310/hta17430.

^ Kim, SE. The benefit-risk consideration in long-term use of alternate-day, low dose aspirin: focus on colorectal cancer prevention.. Annals of gastroenterology : quarterly publication of the Hellenic Society of Gastroenterology. 2014, 27 (1): 87–88. PMID 24714632.

^ U.S. Preventive Services Task, Force. Routine aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the primary prevention of colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007-03-06, 146 (5): 361–4. PMID 17339621. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00008.

^ 66.066.1 National Heart Foundation of Australia (RF/RHD guideline development working group) and the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand. Diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Australia. An evidence-based review (PDF). National Heart Foundation of Australia: 33–37. 2006 [2011-05-09]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2008-07-26).

^ Working Group on Pediatric Acute Rheumatic Fever and Cardiology Chapter of Indian Academy of, Pediatrics; Saxena, A; Kumar, RK; Gera, RP; Radhakrishnan, S; Mishra, S; Ahmed, Z. Consensus guidelines on pediatric acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Indian pediatrics. July 2008, 45 (7): 565–73. PMID 18695275.

^ Hashkes; Tauber, T.; Somekh, E.; Brik, R.; Barash, J.; Mukamel, M.; Harel, L.; Lorber, A.; Berkovitch, M.; Uziel, Y.; Pediatric Rheumatlogy Study Group of Israel. Naproxen as an alternative to aspirin for the treatment of arthritis of rheumatic fever: a randomized trial. The Journal of pediatrics. 2003, 143 (3): 399–401. PMID 14517527. doi:10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00388-3.

^ Rowley, AH; Shulman, ST. Pathogenesis and management of Kawasaki disease. Expert review of anti-infective therapy. February 2010, 8 (2): 197–203. PMC 2845298. PMID 20109049. doi:10.1586/eri.09.109.

^ Baumer, JH; Love, SJ; Gupta, A; Haines, LC; Maconochie, I; Dua, JS. Baumer, J Harry, 编. Salicylate for the treatment of Kawasaki disease in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006-10-18, (4): CD004175. PMID 17054199. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004175.pub2.

^ Duley, L.; Henderson-Smart, D. J.; Meher, S.; King, J. F. Duley, Lelia, 编. Antiplatelet agents for preventing pre-eclampsia and its complications. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online). 2007, (2): CD004659. PMID 17443552. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004659.pub2.

^ Roberge, S. P.; Villa, P.; Nicolaides, K.; Giguère, Y.; Vainio, M.; Bakthi, A.; Ebrashy, A.; Bujold, E. Early Administration of Low-Dose Aspirin for the Prevention of Preterm and Term Preeclampsia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Fetal Diagnosis and Therapy. 2012, 31 (3): 141–146. PMID 22441437. doi:10.1159/000336662.

^ 73.073.173.273.373.4 Aspirin information from Drugs.com. Drugs.com. [2008-05-08]. (原始内容存档于2008-05-09).

^ 74.074.174.2 Oral Aspirin information. First DataBank. [2008-05-08]. (原始内容存档于9 六月 2008). 请检查|archive-date=中的日期值 (帮助)

^ Raithel M; Baenkler HW; Naegel A; Buchwald, F; Schultis, HW; Backhaus, B; Kimpel, S; Koch, H; Mach, K; Hahn, EG; Konturek, PC. Significance of salicylate intolerance in diseases of the lower gastrointestinal tract (PDF). J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2005,. 56 Suppl 5: 89–102. PMID 16247191.

^ Senna GE, Andri G, Dama AR, Mezzelani P, Andri L. Tolerability of imidazole salycilate in aspirin-sensitive patients. Allergy Proc. 1995, 16 (5): 251–4. PMID 8566739. doi:10.2500/108854195778702675.

^ 77.077.1 PDR Guide to Over the Counter (OTC) Drugs. [2008-04-28]. (原始内容存档于10 四月 2008). 请检查|archive-date=中的日期值 (帮助)

^ Livingstone, Frank B. Frequencies of hemoglobin variants: thalassemia, the glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, G6PD variants, and ovalocytosis in human populations. Oxford University Press. 1985. ISBN 0-19-503634-4.

^ Dengue and Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever: Information for Health Care Practitioners. [2008-04-28]. (原始内容存档于17 三月 2008). 请检查|archive-date=中的日期值 (帮助)

^ 80.080.1 引用错误:没有为名为BMJ2002-Macdonald的参考文献提供内容

^ 81.081.181.2 Sørensen HT; Mellemkjaer L; Blot WJ; Nielsen, Gunnar Lauge; Steffensen, Flemming Hald; McLaughlin, Joseph K.; Olsen, Jorgen H. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding associated with use of low-dose aspirin. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2000, 95 (9): 2218–24. PMID 11007221. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02248.x.

^ Delaney JA, Opatrny L, Brophy JM & Suissa S. Drug–drug interactions between antithrombotic medications and the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. CMAJ. 2007, 177 (4): 347–51. PMC 1942107. PMID 17698822. doi:10.1503/cmaj.070186.

^ Wallace, J. L. Prostaglandins, NSAIDs, and Gastric Mucosal Protection: Why Doesn't the Stomach Digest Itself?. Physiological Reviews. 2008, 88 (4): 1547–1565. PMID 18923189. doi:10.1152/physrev.00004.2008.

^ Fiorucci, S.; Santucci, L.; Wallace, J. L.; Sardina, M.; Romano, M.; Del Soldato, P.; Morelli, A. Interaction of a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor with aspirin and NO-releasing aspirin in the human gastric mucosa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003, 100 (19): 10937–10941. PMC 196906. PMID 12960371. doi:10.1073/pnas.1933204100.

^ General Chemistry Online: FAQ: Acids and bases: What is the buffer system in buffered aspirin?. Antoine.frostburg.edu. [2011-05-11].

^ Dammann, H. G.; Saleki, M.; Torz, M.; Schulz, H. U.; Krupp, S.; Schürer, M.; Timm, J.; Gessner, U. Effects of buffered and plain acetylsalicylic acid formulations with and without ascorbic acid on gastric mucosa in healthy subjects. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2004, 19 (3): 367–374. PMID 14984384. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01742.x.

^ Konturek; Kania, J; Hahn, EG; Konturek, JW. Ascorbic acid attenuates aspirin-induced gastric damage: role of inducible nitric oxide synthase. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006,. 57 Suppl 5 (5): 125–36. PMID 17218764.

^ Guitton MJ, Caston J, Ruel J, Johnson RM, Pujol R, Puel JL. Salicylate induces tinnitus through activation of cochlear NMDA receptors. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23 (9): 3944–52. PMID 12736364.

^ 89.089.1 Belay ED, Bresee JS, Holman RC, Khan AS, Shahriari A, Schonberger LB. Reye's syndrome in the United States from 1981 through 1997. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340 (18): 1377–82. PMID 10228187. doi:10.1056/NEJM199905063401801.

^ Reye's syndrome. NHS. [2015-08-14].

^ Berges-Gimeno MP & Stevenson DD. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced reactions and desensitization. J Asthma. 2004, 41 (4): 375–84. PMID 15281324. doi:10.1081/JAS-120037650.

^ Vernooij MW, Haag MD, der Lugt A, Hofman A, Krestin GP, Stricker BH, Breteler MM. Use of antithrombotic drugs and the presence of cerebral microbleeds: the Rotterdam Scan Study. Arch Neurol. 2009, 66 (6): 714–20. PMID 19364926. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2009.42.

^ Gorelick PB. Cerebral microbleeds: evidence of heightened risk associated with aspirin use. Arch Neurol. 2009, 66 (6): 691–3. PMID 19506128. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2009.85.

^ 94.094.1 He, J.; Whelton, P. K.; Vu, B.; Klag, M. J. Aspirin and risk of hemorrhagic stroke: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998, 280 (22): 1930–1935. PMID 9851479. doi:10.1001/jama.280.22.1930.

^ Saloheimo, P.; Ahonen, M.; Juvela, S.; Pyhtinen, J.; Savolainen, E. R.; Hillbom, M. Regular Aspirin-Use Preceding the Onset of Primary Intracerebral Hemorrhage is an Independent Predictor for Death. Stroke. 2005, 37 (1): 129–133. PMID 16322483. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000196991.03618.31.

^ Clerkship Directors in Internal Medicine. Medical knowledge self-assessment program for students 4. Nephrology 227, Item 29. American College of Physicians.

^ Scher, K.S. Unplanned reoperation for bleeding. Am Surg. 1996, 62 (1): 52–55. PMID 8540646.

^ Staff. FDA Strengthens Warning of Heart Attack and Stroke Risk for Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. FDA. 2015-07-09 [2015-07-09].

^ Kreplick, LW. Salicylate Toxicity in Emergency Medicine. Medscape. 2001.

^ Gaudreault P, Temple AR, Lovejoy FH Jr. The relative severity of acute versus chronic salicylate poisoning in children: a clinical comparison. Pediatrics. 1982, 70 (4): 566–9. PMID 7122154. (primary source)

^ Marx, John. Rosen's emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice. Mosby/Elsevier. 2006: 2242. ISBN 978-0-323-02845-5.

^ Morra P, Bartle WR, Walker SE, Lee SN, Bowles SK, Reeves RA. Serum concentrations of salicylic acid following topically applied salicylate derivatives. Ann. Pharmacother. 1996, 30 (9): 935–40. PMID 8876850.

^ R. Baselt. Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man 9th. Seal Beach, California: Biomedical Publications. 2011: 20–23.

^ Information for Healthcare Professionals: Concomitant Use of Ibuprofen and Aspirin. FDA. United States Department of Health and Human Services. September 2006 [2010-11-22]. (原始内容存档于2010-11-13).

^ Katzung. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. McGraw-Hill. 1998: 584.

^ Loh HS, Watters K & Wilson CW. The Effects of Aspirin on the Metabolic Availability of Ascorbic Acid in Human Beings. J Clin Pharmacol. 1973-11-01, 13 (11): 480–6. PMID 4490672. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1973.tb00203.x. (原始内容存档于16 三月 2007). 请检查|archive-date=中的日期值 (帮助)

^ Basu TK. Vitamin C-aspirin interactions. Int J Vitam Nutr Res Suppl. 1982, 23: 83–90. PMID 6811490.

^ Ioannides C, Stone AN, Breacker PJ & Basu TK. Impairment of absorption of ascorbic acid following ingestion of aspirin in guinea pigs. Biochem Pharmacol. 1982, 31 (24): 4035–8. PMID 6818974. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(82)90652-9.

^ Dorsch MP, Lee JS, Lynch DR, Dunn SP, Rodgers JE, Schwartz T, Colby E, Montague D, Smyth SS. Aspirin Resistance in Patients with Stable Coronary Artery Disease with and without a History of Myocardial Infarction. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2007, 41 (May): 737–41. PMID 17456544. doi:10.1345/aph.1H621.

^ Krasopoulos G, Brister SJ, Beattie WS, Buchanan MR. Aspirin "resistance" and risk of cardiovascular morbidity: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008, 336 (7637): 195–8. PMC 2213873. PMID 18202034. doi:10.1136/bmj.39430.529549.BE.

^ Pignatelli P, Di Santo S, Barillà F, Gaudio C, Violi F. Multiple anti-atherosclerotic treatments impair aspirin compliance: effects on aspirin resistance. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2008, 6 (10): 1832–4. PMID 18680540. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03122.x.

^ Tilo Grosser, Susanne Fries, John A. Lawson, Shiv C. Kapoor, Gregory R. Grant and Garret A. FitzGerald. Drug Resistance and Pseudoresistance: An Unintended Consequence of Enteric Coating Aspirin. Circulation. 2013, 127 (3): 377–85 (4 December 2012). PMC 3552520. PMID 23212718. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.117283. Lay summary – The New York Times (4 December 2012).

^ Richard Leroy Myers. The 100 Most Important Chemical Compounds: A Reference Guide. ABC-CLIO. 2007-08-30: 10 [2012-11-18]. ISBN 978-0-313-33758-1.

^ Acetylsalicylic acid. Jinno Laboratory, School of Materials Science, Toyohashi University of Technology. 1996-03-04 [2014-04-12]. (原始内容存档于2012-01-20).

^ EF Reynolds (编). Aspirin and similar analgesic and anti-inflammatory agents. Martindale: The Extra Pharmacopoeia 28th: 234–82. 1982.

^ Acetylsalicylic acid. Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. NIOSH. 2015-02-13.

^ Appendix G: 1989 Air Contaminants Update Project - Exposure Limits NOT in Effect. NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. NIOSH. 2015-02-13.

^ 118.0118.1 Vishweshwar, P.; McMahon, J. A.; Oliveira, M.; Peterson, M. L.; Zaworotko, M. J. The Predictably Elusive Form II of Aspirin. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2005, 127 (48): 16802–16803. PMID 16316223. doi:10.1021/ja056455b.

^ Bond, Andrew D.; Boese, Roland; and Desiraju, Gautam R. On the Polymorphism of Aspirin: Crystalline Aspirin as Intergrowths of Two "Polymorphic" Domains. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2007, 46 (4): 618–622. PMID 17139692. doi:10.1002/anie.200603373.

^ Palleros, Daniel R. Experimental Organic Chemistry. New York: John Wiley & Sons. 2000: 494. ISBN 0-471-28250-2.

^ Barrans, Richard. Aspirin Aging. Newton BBS. [2008-05-08]. (原始内容存档于18 五月 2008). 请检查|archive-date=中的日期值 (帮助)

^ Carstensen, J.T.; F Attarchi and XP Hou. Decomposition of aspirin in the solid state in the presence of limited amounts of moisture. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 1985, 77 (4): 318–21. PMID 4032246. doi:10.1002/jps.2600770407.

^ Vane, John Robert. Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis as a mechanism of action for aspirin-like drugs. Nature – New Biology. 1971, 231 (25): 232–5. PMID 5284360. doi:10.1038/newbio231232a0.

^ Vane JR, Botting RM; Botting. The mechanism of action of aspirin (PDF). Thromb Res. 2003, 110 (5–6): 255–8. PMID 14592543. doi:10.1016/S0049-3848(03)00379-7.

^ The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1982. Nobelprize.or.

^ Moncada, S. Sir John Robert Vane. 29 March 1927 -- 19 November 2004: Elected FRS 1974. Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society (The Royal Society). 2006-12-01, 52 (0): 401–411. ISSN 0080-4606. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2006.0027.

^ Mastrangelo, D.; Wisard, M.; Rohner, S.; Leisinger, H.; Iselin, C. E. Diclofenac and NS-398, a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, decrease agonist-induced contractions of the pig isolated ureter. Urological Research. 2000-12-01, 28 (6): 376–382. ISSN 0300-5623. PMID 11221916.

^ Prusakiewicz, Jeffery J.; Duggan, Kelsey C.; Rouzer, Carol A.; Marnett, Lawrence J. Differential Sensitivity and Mechanism of Inhibition of COX-2 Oxygenation of Arachidonic Acid and 2-Arachidonoylglycerol by Ibuprofen and Mefenamic Acid. Biochemistry. 2009-07-20, 48 (31): 7353–7355. PMC 2720641. PMID 19603831. doi:10.1021/bi900999z (英语).

^ Aspirin in Heart Attack and Stroke Prevention. American Heart Association. [2008-05-08]. (原始内容存档于2008-03-31).

^ Tohgi, H; S Konno, K Tamura, B Kimura and K Kawano. Effects of low-to-high doses of aspirin on platelet aggregability and metabolites of thromboxane A2 and prostacyclin. Stroke. 1992, 23 (10): 1400–1403. PMID 1412574. doi:10.1161/01.STR.23.10.1400.

^ Veale, W. L.; Cooper, K. E.; Pittman, Q. J. Role of Prostaglandins in Fever and Temperature Regulation: 145–167. 1977. PMC 3081099. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-8055-3_6.

^ Ricciotti, E.; FitzGerald, G. A. Prostaglandins and Inflammation. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2011, 31 (5): 986–1000. ISSN 1079-5642. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.207449.

^ Rumin, Raphel. Rubin's Pathology 6th edition. USA: Wolters Kluwer. 2011: 59. ISBN 978-1-4511-0912-2.

^ 134.0134.1134.2 英國國家處方集 45. British Medical Journal and 英國皇家藥劑師協會. 2003.

^ Achhrish goel, Ruchi gupta Anubhav goswami Madhu soodan sharma Yogesh sharma. Pharmacokinetic Solubility And Dissolution Profile of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs 2 (3). 2011.

^ 引用错误:没有为名为cox3article的参考文献提供内容

^ Martínez-González J, Badimon L; Badimon. Mechanisms underlying the cardiovascular effects of COX-inhibition: benefits and risks. Curr Pharm Des. 2007, 13 (22): 2215–27. PMID 17691994. doi:10.2174/138161207781368774.

^ Funk CD, FitzGerald GA; Fitzgerald. COX-2 inhibitors and cardiovascular risk. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. November 2007, 50 (5): 470–9. PMID 18030055. doi:10.1097/FJC.0b013e318157f72d.

^ Romano M, Cianci E, Simiele F, Recchiuti A. Lipoxins and aspirin-triggered lipoxins in resolution of inflammation. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2015, 760: 49–63. PMID 25895638. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.03.083.

^ Serhan CN, Chiang N. Resolution phase lipid mediators of inflammation: agonists of resolution. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2013, 13 (4): 632–40. PMC 3732499. PMID 23747022. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2013.05.012.

^ Weylandt KH. Docosapentaenoic acid derived metabolites and mediators - The new world of lipid mediator medicine in a nutshell. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2015, 785: 108–115. PMID 26546723. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.11.002.

^ Somasundaram; Sigthorsson, G; Simpson, RJ; Watts, J; Jacob, M; Tavares, IA; Rafi, S; Roseth, A; Foster, R; 等. Uncoupling of intestinal mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and inhibition of cyclooxygenase are required for the development of NSAID-enteropathy in the rat. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000, 14 (5): 639–650. PMID 10792129. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00723.x.

^ Paul-Clark, Mark J.; Cao, Thong van; Moradi-Bidhendi, Niloufar; Cooper, Dianne & Gilroy, Derek W. 15-epi-lipoxin A4–mediated Induction of Nitric Oxide Explains How Aspirin Inhibits Acute Inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2004, 200 (1): 69–78. PMC 2213311. PMID 15238606. doi:10.1084/jem.20040566.

^ McCarty, M. F.; Block, K. I. Preadministration of high-dose salicylates, suppressors of NF-kappaB activation, may increase the chemosensitivity of many cancers: an example of proapoptotic signal modulation therapy. Integr Cancer Ther. 2006, 5 (3): 252–268. PMID 16880431. doi:10.1177/1534735406291499.

^ Hawley, S. A.; Fullerton, M. D.; Ross, F. A.; Schertzer, J. D.; Chevtzoff, C.; Walker, K. J.; Peggie, M. W.; Zibrova, D.; Green, K. A.; Mustard, K. J.; Kemp, B. E.; Sakamoto, K.; Steinberg, G. R.; Hardie, D. G. The Ancient Drug Salicylate Directly Activates AMP-Activated Protein Kinase. Science. 2012, 336 (6083): 918–922. PMC 3399766. PMID 22517326. doi:10.1126/science.1215327.

^ Raffensperger, Lisa. Clues to aspirin's anti-cancer effects revealed. New Scientist. 2012-04-19, 214 (2862): 16. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(12)61073-2.

^ Bhat. Aspirin inhibits camptothecin-induced p21CIP1 levels and potentiates apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. International Journal of Oncology. 2009, 34 (3). PMID 19212664. doi:10.3892/ijo_00000185.

^ Bhat. Does aspirin acetylate multiple cellular proteins? (Review). Molecular Medicine Reports. 2009, 2 (4). PMID 21475861. doi:10.3892/mmr_00000132.

^ Aspirin monograph: dosages, etc. Medscape.com. [2011-05-11].

^ 150.0150.1150.2 Aspirin: More Evidence That Low Dose Is All That Is Needed (from Medscape). Cme.medscape.com. [2011-05-11].

^ British National Formulary for Children. British Medical Journal and Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2006.

^ Ferguson, RK; Boutros, AR. Death following self-poisoning with aspirin. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1970-08-17, 213 (7): 1186–8. PMID 5468267. doi:10.1001/jama.213.7.1186.

^ Kaufman, FL; Dubansky, AS. Darvon poisoning with delayed salicylism: a case report. Pediatrics. April 1970, 49 (4): 610–1. PMID 5013423.

^ 154.0154.1154.2 Levy, G; Tsuchiya, T. Salicylate accumulation kinetics in man. New England Journal of Medicine. 1972-08-31, 287 (9): 430–2. PMID 5044917. doi:10.1056/NEJM197208312870903.

^ 2,3-Dihydroxybenzoic acid is a product of human aspirin metabolism. Martin Grootveld and Barry Halliwell, Biochemical Pharmacology, Volume 37, Issue 2, 15 January 1988, pages 271–280, doi:10.1016/0006-2952(88)90729-0

^ Hartwig, Otto H. Pharmacokinetic considerations of common analgesics and antipyretics. American Journal of Medicine. 1983-11-14, 75 (5A): 30–7. PMID 6606362. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(83)90230-9.

^ Done, AK. Salicylate intoxication. Significance of measurements of salicylate in blood in cases of acute ingestion. Pediatrics. November 1960, 26: 800–7. PMID 13723722.

^ Chyka PA, Erdman AR, Christianson G, Wax PM, Booze LL, Manoguerra AS, Caravati EM, Nelson LS, Olson KR, Cobaugh DJ, Scharman EJ, Woolf AD, Troutman WG; Americal Association of Poison Control Centers; Healthcare Systems Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services. Salicylate poisoning: an evidence-based consensus guideline for out-of-hospital management. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2007, 45 (2): 95–131. PMID 17364628. doi:10.1080/15563650600907140.

^ Prescott LF, Balali-Mood M, Critchley JA, Johnstone AF, Proudfoot AT; Balali-Mood; Critchley; Johnstone; Proudfoot. Diuresis or urinary alkalinisation for salicylate poisoning?. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1982, 285 (6352): 1383–6. PMC 1500395. PMID 6291695. doi:10.1136/bmj.285.6352.1383.

^ Dargan PI, Wallace CI, Jones AL.; Wallace; Jones. An evidenced based flowchart to guide the management of acute salicylate (aspirin) overdose. Emerg Med J. 2002, 19 (3): 206–9. PMC 1725844. PMID 11971828. doi:10.1136/emj.19.3.206.

^ Mary Bellis. History of aspirin. Inventors.about.com. 2010-06-16 [2011-05-11].

^ Gerhardt, Ch. Untersuchungen über die wasserfreien organischen Säuren [Investigations into anhydrous organic acids]. Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. 1853, 87: 149–179. doi:10.1002/jlac.18530870107 (德语). 特别是162–163页.

^ von Gilm H. Acetylderivate der Phloretin- und Salicylsäure [Acetyl derivatives of phloretic and salicylic acids]. Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. 1859, 112 (2): 180–182. doi:10.1002/jlac.18591120207 (德语).

^ Schröder, Prinzhorn, Kraut K; Prinzhorn; Kraut. Ueber Salicylverbindungen [On compounds of salicylic acid]. Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. 1869, 150 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1002/jlac.18691500102 (德语). 特别是9–13页,乙酰水杨酸的结构在12页上。

^ 引用错误:没有为名为ReferenceA的参考文献提供内容

^ Mahdi, JG; Mahdi, AJ, Mahdi, AJ, Bowen, ID. The historical analysis of aspirin discovery, its relation to the willow tree and antiproliferative and anticancer potential. Cell proliferation. April 2006, 39 (2): 147–55. PMID 16542349. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2184.2006.00377.x.

^ Singer, H. Ueber Aspirin. Pflügers Archiv: European Journal of Physiology. 1901, 84 (11–12): 527–546. doi:10.1007/BF01769129.

^ Jeffreys 2005,第73页

^ Starko, Karen M. Salicylates and Pandemic Influenza Mortality, 1918–1919 Pharmacology, Pathology, and Historic Evidence. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009, 49 (9): 1405–1410. PMID 19788357. doi:10.1086/606060.

^ Jeffreys 2005,第136–142, 151–152页

^ Bayer patents aspirin – This Day in History – 3/6/1899. History.com. [2011-05-11]. (原始内容存档于2009-10-08).

^ Jeffreys 2005,第212–217页

^ Jeffreys 2005,第226–231页

^ Jeffreys 2005,第267–269页

^

Treaty of Versailles, Part X, Section IV, Article 298: Annex, Paragraph 5. 1919-06-28 [2008-10-25].

^

Mehta, Aalok. Aspirin. Chemical & Engineering News. 2005, 83 (25) [2008-10-23].

^ The Centenary of Aspirin. Ul.ie. 1999-03-06 [2011-05-11].

^ Aspirin: the versatile drug. CBC News. 2009-05-28.

^

Cheng, Tsung O. The History of Aspirin. Texas Heart Institute Journal. 2007, 34 (3): 392–393. PMC 1995051. PMID 17948100.

^ American Academy of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. ASPIRIN Veterinary—Systemic (PDF). [2016-02-25]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2016-02-25).

^ Crosby, Janet Tobiassen. Veterinary Questions and Answers. About.com. 2006 [2007-09-05]. (原始内容存档于2007-09-08).

^ Cambridge H, Lees P, Hooke RE, Russell CS; Lees; Hooke; Russell. Antithrombotic actions of aspirin in the horse. Equine Vet J. 1991, 23 (2): 123–7. PMID 1904347. doi:10.1111/j.2042-3306.1991.tb02736.x.

^ Lappin, Michael R. (编). Feline internal medicine secrets. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus. 2001: 160. ISBN 1-56053-461-3.

^ Analgesics (Toxicity): Toxicities from Human Drugs: Merck Veterinary Manual. [2015-08-24].

^ Plants Poisonous to Livestock - Cornell University Department of Animal Science. [2015-08-24].

延伸阅读

Jeffreys, Diarmuid. Aspirin: The Remarkable Story of a Wonder Drug. Bloomsbury USA. 2005-08-11. ISBN 1-58234-600-3.

参见

- 世界卫生组织基本药物标准清单

外部链接

维基共享资源中相关的多媒体资源:阿司匹林 |

- NextBio中Aspirin的条目

- 阿司匹林降低癌症发病率

- Aspirin 元素周期表视频(诺丁汉大学)

- 阿司匹林背后的科学

Roberts, Shauna. Take two: Aspirin. American Chemical Society.New uses and new dangers are still being discovered as aspirin enters its 2nd century(阿司匹林面世后一百多年,人们仍在发现它的新用途和风险)

Ling, Greg. Aspirin. How Products are Made 1. Thomson Gale. 2005.

- 美国国家医学图书馆:药品信息门户 – 阿司匹林

- CDC – 美国国家职业安全卫生研究所危险化学品袖珍指南 – 乙酰水杨酸

- 阿司匹林的十大妙用

- 电影《阿司匹林》 (2006)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

|