Hypertension

| Hypertension | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Arterial hypertension, high blood pressure |

| |

| Automated arm blood pressure meter showing arterial hypertension (shown a systolic blood pressure 158 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure 99 mmHg and heart rate of 80 beats per minute) | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

| Symptoms | None[1] |

| Complications | Coronary artery disease, stroke, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, vision loss, chronic kidney disease, dementia[2][3][4] |

| Causes | Usually lifestyle and genetic factors[5][6] |

| Risk factors | Excess salt, excess body weight, smoking, alcohol[1][5] |

| Diagnostic method | Resting blood pressure 130/80 or 140/90 mmHg[5][7] |

| Treatment | Lifestyle changes, medications[8] |

| Frequency | 16–37% globally[5] |

| Deaths | 9.4 million / 18% (2010)[9] |

Hypertension (HTN or HT), also known as high blood pressure (HBP), is a long-term medical condition in which the blood pressure in the arteries is persistently elevated.[10] High blood pressure typically does not cause symptoms.[1] Long-term high blood pressure, however, is a major risk factor for coronary artery disease, stroke, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, peripheral vascular disease, vision loss, chronic kidney disease, and dementia.[2][3][4][11]

High blood pressure is classified as either primary (essential) high blood pressure or secondary high blood pressure.[5] About 90–95% of cases are primary, defined as high blood pressure due to nonspecific lifestyle and genetic factors.[5][6] Lifestyle factors that increase the risk include excess salt in the diet, excess body weight, smoking, and alcohol use.[1][5] The remaining 5–10% of cases are categorized as secondary high blood pressure, defined as high blood pressure due to an identifiable cause, such as chronic kidney disease, narrowing of the kidney arteries, an endocrine disorder, or the use of birth control pills.[5]

Blood pressure is expressed by two measurements, the systolic and diastolic pressures, which are the maximum and minimum pressures, respectively.[1] For most adults, normal blood pressure at rest is within the range of 100–130 millimeters mercury (mmHg) systolic and 60–80 mmHg diastolic.[7][12] For most adults, high blood pressure is present if the resting blood pressure is persistently at or above 130/80 or 140/90 mmHg.[5][7] Different numbers apply to children.[13]Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring over a 24-hour period appears more accurate than office-based blood pressure measurement.[5][10]

Lifestyle changes and medications can lower blood pressure and decrease the risk of health complications.[8] Lifestyle changes include weight loss, physical exercise, decreased salt intake, reducing alcohol intake and a healthy diet.[5] If lifestyle changes are not sufficient then blood pressure medications are used.[8] Up to three medications can control blood pressure in 90% of people.[5] The treatment of moderately high arterial blood pressure (defined as >160/100 mmHg) with medications is associated with an improved life expectancy.[14] The effect of treatment of blood pressure between 130/80 mmHg and 160/100 mmHg is less clear, with some reviews finding benefit[7][15][16] and others finding unclear benefit.[17][18][19] High blood pressure affects between 16 and 37% of the population globally.[5] In 2010 hypertension was believed to have been a factor in 18% of all deaths (9.4 million globally).[9]

Contents

1 Signs and symptoms

1.1 Secondary hypertension

1.2 Hypertensive crisis

1.3 Pregnancy

1.4 Children

2 Causes

2.1 Primary hypertension

2.2 Secondary hypertension

3 Pathophysiology

4 Diagnosis

4.1 Adults

4.2 Children

5 Prevention

6 Management

6.1 Target blood pressure

6.2 Lifestyle modifications

6.3 Medications

6.4 Resistant hypertension

7 Epidemiology

7.1 Adults

7.2 Children

8 Outcomes

9 History

9.1 Measurement

9.2 Identification

9.3 Treatment

10 Society and culture

10.1 Awareness

10.2 Economics

11 Research

12 Other animals

12.1 Cats

12.2 Dogs

13 References

14 Further reading

15 External links

Signs and symptoms

Hypertension is rarely accompanied by symptoms, and its identification is usually through screening, or when seeking healthcare for an unrelated problem. Some people with high blood pressure report headaches (particularly at the back of the head and in the morning), as well as lightheadedness, vertigo, tinnitus (buzzing or hissing in the ears), altered vision or fainting episodes.[20] These symptoms, however, might be related to associated anxiety rather than the high blood pressure itself.[21]

On physical examination, hypertension may be associated with the presence of changes in the optic fundus seen by ophthalmoscopy.[22] The severity of the changes typical of hypertensive retinopathy is graded from I–IV; grades I and II may be difficult to differentiate.[22] The severity of the retinopathy correlates roughly with the duration or the severity of the hypertension.[20]

Secondary hypertension

Hypertension with certain specific additional signs and symptoms may suggest secondary hypertension, i.e. hypertension due to an identifiable cause. For example, Cushing's syndrome frequently causes truncal obesity, glucose intolerance, moon face, a hump of fat behind the neck/shoulder (referred to as a buffalo hump), and purple abdominal stretch marks.[23]Hyperthyroidism frequently causes weight loss with increased appetite, fast heart rate, bulging eyes, and tremor. Renal artery stenosis (RAS) may be associated with a localized abdominal bruit to the left or right of the midline (unilateral RAS), or in both locations (bilateral RAS). Coarctation of the aorta frequently causes a decreased blood pressure in the lower extremities relative to the arms, or delayed or absent femoral arterial pulses. Pheochromocytoma may cause abrupt ("paroxysmal") episodes of hypertension accompanied by headache, palpitations, pale appearance, and excessive sweating.[23]

Hypertensive crisis

Severely elevated blood pressure (equal to or greater than a systolic 180 or diastolic of 110) is referred to as a hypertensive crisis. Hypertensive crisis is categorized as either hypertensive urgency or hypertensive emergency, according to the absence or presence of end organ damage, respectively.[24][25]

In hypertensive urgency, there is no evidence of end organ damage resulting from the elevated blood pressure. In these cases, oral medications are used to lower the BP gradually over 24 to 48 hours.[26]

In hypertensive emergency, there is evidence of direct damage to one or more organs.[27][28] The most affected organs include the brain, kidney, heart and lungs, producing symptoms which may include confusion, drowsiness, chest pain and breathlessness.[26] In hypertensive emergency, the blood pressure must be reduced more rapidly to stop ongoing organ damage,[26] however, there is a lack of randomized controlled trial evidence for this approach.[28]

Pregnancy

Hypertension occurs in approximately 8–10% of pregnancies.[23] Two blood pressure measurements six hours apart of greater than 140/90 mm Hg is diagnostic of hypertension in pregnancy.[29] High blood pressure in pregnancy can be classified as pre-existing hypertension, gestational hypertension, or pre-eclampsia.[30]

Pre-eclampsia is a serious condition of the second half of pregnancy and following delivery characterised by increased blood pressure and the presence of protein in the urine.[23] It occurs in about 5% of pregnancies and is responsible for approximately 16% of all maternal deaths globally.[23] Pre-eclampsia also doubles the risk of death of the baby around the time of birth.[23] Usually there are no symptoms in pre-eclampsia and it is detected by routine screening. When symptoms of pre-eclampsia occur the most common are headache, visual disturbance (often "flashing lights"), vomiting, pain over the stomach, and swelling. Pre-eclampsia can occasionally progress to a life-threatening condition called eclampsia, which is a hypertensive emergency and has several serious complications including vision loss, brain swelling, seizures, kidney failure, pulmonary edema, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (a blood clotting disorder).[23][31]

In contrast, gestational hypertension is defined as new-onset hypertension during pregnancy without protein in the urine.[30]

Children

Failure to thrive, seizures, irritability, lack of energy, and difficulty in breathing[32] can be associated with hypertension in newborns and young infants. In older infants and children, hypertension can cause headache, unexplained irritability, fatigue, failure to thrive, blurred vision, nosebleeds, and facial paralysis.[32][33]

Causes

Primary hypertension

Hypertension results from a complex interaction of genes and environmental factors. Numerous common genetic variants with small effects on blood pressure have been identified[34] as well as some rare genetic variants with large effects on blood pressure.[35] Also, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified 35 genetic loci related to blood pressure; 12 of these genetic loci influencing blood pressure were newly found.[36] Sentinel SNP for each new genetic locus identified has shown an association with DNA methylation at multiple nearby CpG sites. These sentinel SNP are located within genes related to vascular smooth muscle and renal function. DNA methylation might affect in some way linking common genetic variation to multiple phenotypes even though mechanisms underlying these associations are not understood. Single variant test performed in this study for the 35 sentinel SNP (known and new) showed that genetic variants singly or in aggregate contribute to risk of clinical phenotypes related to high blood pressure.[36]

Blood pressure rises with aging and the risk of becoming hypertensive in later life is considerable.[37] Several environmental factors influence blood pressure. High salt intake raises the blood pressure in salt sensitive individuals; lack of exercise, obesity, and depression[38] can play a role in individual cases. The possible roles of other factors such as caffeine consumption,[39] and vitamin D deficiency[40] are less clear. Insulin resistance, which is common in obesity and is a component of syndrome X (or the metabolic syndrome), is also thought to contribute to hypertension.[41] One review suggests that sugar may play an important role in hypertension and salt is just an innocent bystander.[42]

Events in early life, such as low birth weight, maternal smoking, and lack of breastfeeding may be risk factors for adult essential hypertension, although the mechanisms linking these exposures to adult hypertension remain unclear.[43] An increased rate of high blood urea has been found in untreated people with hypertension in comparison with people with normal blood pressure, although it is uncertain whether the former plays a causal role or is subsidiary to poor kidney function.[44] Average blood pressure may be higher in the winter than in the summer.[45]

Secondary hypertension

Secondary hypertension results from an identifiable cause. Kidney disease is the most common secondary cause of hypertension.[23] Hypertension can also be caused by endocrine conditions, such as Cushing's syndrome, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, acromegaly, Conn's syndrome or hyperaldosteronism, renal artery stenosis (from atherosclerosis or fibromuscular dysplasia), hyperparathyroidism, and pheochromocytoma.[23][46] Other causes of secondary hypertension include obesity, sleep apnea, pregnancy, coarctation of the aorta, excessive eating of liquorice, excessive drinking of alcohol, and certain prescription medicines, herbal remedies, and illegal drugs such as cocaine and methamphetamine.[23][47]Arsenic exposure through drinking water has been shown to correlate with elevated blood pressure.[48][49]

A 2018 review found that any alcohol increased blood pressure in males while over one or two drinks increased the risk in females.[50]

Pathophysiology

Determinants of mean arterial pressure

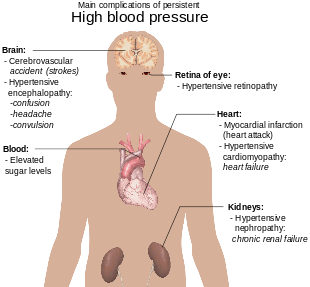

Illustration depicting the effects of high blood pressure

In most people with established essential hypertension, increased resistance to blood flow (total peripheral resistance) accounts for the high pressure while cardiac output remains normal.[51] There is evidence that some younger people with prehypertension or 'borderline hypertension' have high cardiac output, an elevated heart rate and normal peripheral resistance, termed hyperkinetic borderline hypertension.[52] These individuals develop the typical features of established essential hypertension in later life as their cardiac output falls and peripheral resistance rises with age.[52] Whether this pattern is typical of all people who ultimately develop hypertension is disputed.[53] The increased peripheral resistance in established hypertension is mainly attributable to structural narrowing of small arteries and arterioles,[54] although a reduction in the number or density of capillaries may also contribute.[55]

It is not clear whether or not vasoconstriction of arteriolar blood vessels plays a role in hypertension.[56] Hypertension is also associated with decreased peripheral venous compliance[57] which may increase venous return, increase cardiac preload and, ultimately, cause diastolic dysfunction.

Pulse pressure (the difference between systolic and diastolic blood pressure) is frequently increased in older people with hypertension. This can mean that systolic pressure is abnormally high, but diastolic pressure may be normal or low a condition termed isolated systolic hypertension.[58] The high pulse pressure in elderly people with hypertension or isolated systolic hypertension is explained by increased arterial stiffness, which typically accompanies aging and may be exacerbated by high blood pressure.[59]

Many mechanisms have been proposed to account for the rise in peripheral resistance in hypertension. Most evidence implicates either disturbances in the kidneys' salt and water handling (particularly abnormalities in the intrarenal renin–angiotensin system)[60] or abnormalities of the sympathetic nervous system.[61] These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive and it is likely that both contribute to some extent in most cases of essential hypertension. It has also been suggested that endothelial dysfunction and vascular inflammation may also contribute to increased peripheral resistance and vascular damage in hypertension.[62][63]Interleukin 17 has garnered interest for its role in increasing the production of several other immune system chemical signals thought to be involved in hypertension such as tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 1, interleukin 6, and interleukin 8.[64]

Consumption of excessive sodium and/or insufficient potassium leads to excessive intracellular sodium, which contracts vascular smooth muscle, restricting blood flow and so increases blood pressure.[65][66]

Diagnosis

| System | Tests |

|---|---|

Kidney | Microscopic urinalysis, protein in the urine, BUN and/or creatinine |

Endocrine | Serum sodium, potassium, calcium, TSH |

Metabolic | Fasting blood glucose, HDL, LDL, and total cholesterol, triglycerides |

| Other | Hematocrit, electrocardiogram, and chest radiograph |

| Sources: Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine[67] and others[68][69][70][71][72] | |

Hypertension is diagnosed on the basis of a persistently high resting blood pressure. The American Heart Association recommends at least three resting measurements on at least two separate health care visits.[73]The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends ambulatory blood pressure monitoring to confirm the diagnosis of hypertension if a clinic blood pressure is 140/90 mmHg or higher.[74]

For an accurate diagnosis of hypertension to be made, it is essential for proper blood pressure measurement technique to be used.[75] Improper measurement of blood pressure is common and can change the blood pressure reading by up to 10 mmHg, which can lead to misdiagnosis and misclassification of hypertension.[75] Correct blood pressure measurement technique involves several steps. Proper blood pressure measurement requires the person whose blood pressure is being measured to sit quietly for at least five minutes which is then followed by application of a properly fitted blood pressure cuff to a bare upper arm.[75] The person should be seated with their back supported, feet flat on the floor, and with their legs uncrossed.[75] The person whose blood pressure is being measured should avoid talking or moving during this process.[75] The arm being measured should be supported on a flat surface at the level of the heart.[75] Blood pressure measurement should be done in a quiet room so the medical professional checking the blood pressure can hear the Korotkoff sounds while listening to the brachial artery with a stethoscope for accurate blood pressure measurements.[75][76] The blood pressure cuff should be deflated slowly (2-3 mmHg per second) while listening for the Korotkoff sounds.[76] The bladder should be emptied before a person's blood pressure is measured since this can increase blood pressure by up to 15/10 mmHg.[75] Multiple blood pressure readings (at least two) spaced 1–2 minutes apart should be obtained to ensure accuracy.[76] Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring over 12 to 24 hours is the most accurate method to confirm the diagnosis.[77]

An exception to this is those with very high blood pressure readings especially when there is poor organ function.[78] Initial assessment of the hypertensive people should include a complete history and physical examination. With the availability of 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitors and home blood pressure machines, the importance of not wrongly diagnosing those who have white coat hypertension has led to a change in protocols. In the United Kingdom, current best practice is to follow up a single raised clinic reading with ambulatory measurement, or less ideally with home blood pressure monitoring over the course of 7 days.[78] The United States Preventive Services Task Force also recommends getting measurements outside of the healthcare environment.[79]Pseudohypertension in the elderly or noncompressibility artery syndrome may also require consideration. This condition is believed to be due to calcification of the arteries resulting in abnormally high blood pressure readings with a blood pressure cuff while intra arterial measurements of blood pressure are normal.[80]Orthostatic hypertension is when blood pressure increases upon standing.[81]

Once the diagnosis of hypertension has been made, healthcare providers should attempt to identify the underlying cause based on risk factors and other symptoms, if present. Secondary hypertension is more common in preadolescent children, with most cases caused by kidney disease. Primary or essential hypertension is more common in adolescents and has multiple risk factors, including obesity and a family history of hypertension.[82] Laboratory tests can also be performed to identify possible causes of secondary hypertension, and to determine whether hypertension has caused damage to the heart, eyes, and kidneys. Additional tests for diabetes and high cholesterol levels are usually performed because these conditions are additional risk factors for the development of heart disease and may require treatment.[6]

Serum creatinine is measured to assess for the presence of kidney disease, which can be either the cause or the result of hypertension. Serum creatinine alone may overestimate glomerular filtration rate and recent guidelines advocate the use of predictive equations such as the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula to estimate glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).[27] eGFR can also provide a baseline measurement of kidney function that can be used to monitor for side effects of certain anti-hypertensive drugs on kidney function. Additionally, testing of urine samples for protein is used as a secondary indicator of kidney disease. Electrocardiogram (EKG/ECG) testing is done to check for evidence that the heart is under strain from high blood pressure. It may also show whether there is thickening of the heart muscle (left ventricular hypertrophy) or whether the heart has experienced a prior minor disturbance such as a silent heart attack. A chest X-ray or an echocardiogram may also be performed to look for signs of heart enlargement or damage to the heart.[23]

Adults

Category | Systolic, mmHg | Diastolic, mmHg |

|---|---|---|

Hypotension | < 90 | < 60 |

Normal | 90–119[7] 90–129[83] | 60–79[7] 60–84[83] |

Prehypertension (high normal, elevated[7]) | 120–129[7] 130–139[83][84] | 60–79[7] 85–89[83][84] |

Stage 1 hypertension | 130-139[7] 140–159[83] | 80-89[7] 90–99[83] |

Stage 2 hypertension | >140[7] 160–179[83] | >90[7] 100–109[83] |

Hypertensive crises | ≥ 180[7] | ≥ 120[7] |

Isolated systolic hypertension | ≥ 160[7] | < 90 to 110[7] |

In people aged 18 years or older hypertension is defined as either a systolic or a diastolic blood pressure measurement consistently higher than an accepted normal value (this is above 129 or 139 mmHg systolic, 89 mmHg diastolic depending on the guideline).[5][7] Other thresholds are used (135 mmHg systolic or 85 mmHg diastolic) if measurements are derived from 24-hour ambulatory or home monitoring.[78] Recent international hypertension guidelines have also created categories below the hypertensive range to indicate a continuum of risk with higher blood pressures in the normal range. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC7) published in 2003[27] uses the term prehypertension for blood pressure in the range 120–139 mmHg systolic or 80–89 mmHg diastolic, while European Society of Hypertension Guidelines (2007)[85] and British Hypertension Society (BHS) IV (2004)[86] use optimal, normal and high normal categories to subdivide pressures below 140 mmHg systolic and 90 mmHg diastolic. Hypertension is also sub-classified: JNC7 distinguishes hypertension stage I, hypertension stage II, and isolated systolic hypertension. Isolated systolic hypertension refers to elevated systolic pressure with normal diastolic pressure and is common in the elderly.[27] The ESH-ESC Guidelines (2007)[85] and BHS IV (2004)[86] additionally define a third stage (stage III hypertension) for people with systolic blood pressure exceeding 179 mmHg or a diastolic pressure over 109 mmHg. Hypertension is classified as "resistant" if medications do not reduce blood pressure to normal levels.[27] In November 2017, the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology published a joint guideline which updates the recommendations of the JNC7 report.[87]

Children

Hypertension occurs in around 0.2 to 3% of newborns; however, blood pressure is not measured routinely in healthy newborns.[33] Hypertension is more common in high risk newborns. A variety of factors, such as gestational age, postconceptional age and birth weight needs to be taken into account when deciding if a blood pressure is normal in a newborn.[33]

Hypertension defined as elevated blood pressure over several visits affects 1% to 5% of children and adolescents and is associated with long term risks of ill-health.[88] Blood pressure rises with age in childhood and, in children, hypertension is defined as an average systolic or diastolic blood pressure on three or more occasions equal or higher than the 95th percentile appropriate for the sex, age and height of the child. High blood pressure must be confirmed on repeated visits however before characterizing a child as having hypertension.[88] Prehypertension in children has been defined as average systolic or diastolic blood pressure that is greater than or equal to the 90th percentile, but less than the 95th percentile.[88] In adolescents, it has been proposed that hypertension and pre-hypertension are diagnosed and classified using the same criteria as in adults.[88]

The value of routine screening for hypertension in children over the age of 3 years is debated.[89][90] In 2004 the National High Blood Pressure Education Program recommended that children aged 3 years and older have blood pressure measurement at

least once at every health care visit[88] and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and American Academy of Pediatrics made a similar recommendation.[91] However, the American Academy of Family Physicians[92] supports the view of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force that the available evidence is insufficient to determine the balance of benefits and harms of screening for hypertension in children and adolescents who do not have symptoms.[93]

Prevention

Much of the disease burden of high blood pressure is experienced by people who are not labeled as hypertensive.[86] Consequently, population strategies are required to reduce the consequences of high blood pressure and reduce the need for antihypertensive medications. Lifestyle changes are recommended to lower blood pressure, before starting medications. The 2004 British Hypertension Society guidelines[86] proposed lifestyle changes consistent with those outlined by the US National High BP Education Program in 2002[94] for the primary prevention of hypertension:

- maintain normal body weight for adults (e.g. body mass index 20–25 kg/m2)

- reduce dietary sodium intake to <100 mmol/ day (<6 g of sodium chloride or <2.4 g of sodium per day)

- engage in regular aerobic physical activity such as brisk walking (≥30 min per day, most days of the week)

- limit alcohol consumption to no more than 3 units/day in men and no more than 2 units/day in women

- consume a diet rich in fruit and vegetables (e.g. at least five portions per day);

Effective lifestyle modification may lower blood pressure as much as an individual antihypertensive medication. Combinations of two or more lifestyle modifications can achieve even better results.[86] There is considerable evidence that reducing dietary salt intake lowers blood pressure, but whether this translates into a reduction in mortality and cardiovascular disease remains uncertain.[95] Estimated sodium intake ≥6g/day and <3g/day are both associated with high risk of death or major cardiovascular disease, but the association between high sodium intake and adverse outcomes is only observed in people with hypertension.[96] Consequently, in the absence of results from randomized controlled trials, the wisdom of reducing levels of dietary salt intake below 3g/day has been questioned.[95]

Management

According to one review published in 2003, reduction of the blood pressure by 5 mmHg can decrease the risk of stroke by 34%, of ischemic heart disease by 21%, and reduce the likelihood of dementia, heart failure, and mortality from cardiovascular disease.[97]

Target blood pressure

Various expert groups have produced guidelines regarding how low the blood pressure target should be when a person is treated for hypertension. These groups recommend a target below the range 140–160 / 90–100 mmHg for the general population.[13][98][99][100][101] Cochrane reviews recommend similar targets for subgroups such as people with diabetes[102] and people with prior cardiovascular disease.[103]

Many expert groups recommend a slightly higher target of 150/90 mmHg for those over somewhere between 60 and 80 years of age.[98][99][100][104] The JNC-8 and American College of Physicians recommend the target of 150/90 mmHg for those over 60 years of age,[13][105] but some experts within these groups disagree with this recommendation.[106] Some expert groups have also recommended slightly lower targets in those with diabetes[98] or chronic kidney disease with protein loss in the urine,[107] but others recommend the same target as for the general population.[13][102] The issue of what is the best target and whether targets should differ for high risk individuals is unresolved,[108] although some experts propose more intensive blood pressure lowering than advocated in some guidelines.[109]

Lifestyle modifications

The first line of treatment for hypertension is lifestyle changes, including dietary changes, physical exercise, and weight loss. Though these have all been recommended in scientific advisories,[110] a Cochrane systematic review found no evidence for effects of weight loss diets on death, long-term complications or adverse events in persons with hypertension.[111] The review did find a decrease in blood pressure.[111] Their potential effectiveness is similar to and at times exceeds a single medication.[12] If hypertension is high enough to justify immediate use of medications, lifestyle changes are still recommended in conjunction with medication.

Dietary changes shown to reduce blood pressure include diets with low sodium,[112][113][114] the DASH diet,[115]vegetarian diets,[116] and green tea consumption.[117][118][119][120]

Increasing dietary potassium has a potential benefit for lowering the risk of hypertension.[121][122] The 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) stated that potassium is one of the shortfall nutrients which is under-consumed in the United States.[123]

Physical exercise regimens which are shown to reduce blood pressure include isometric resistance exercise, aerobic exercise, resistance exercise, and device-guided breathing.[124]

Stress reduction techniques such as biofeedback or transcendental meditation may be considered as an add-on to other treatments to reduce hypertension, but do not have evidence for preventing cardiovascular disease on their own.[124][125][126] Self-monitoring and appointment reminders might support the use of other strategies to improve blood pressure control, but need further evaluation.[127]

Medications

Several classes of medications, collectively referred to as antihypertensive medications, are available for treating hypertension.

First-line medications for hypertension include thiazide-diuretics, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors), and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs).[13] These medications may be used alone or in combination (ACE inhibitors and ARBs are not recommended for use in combination); the latter option may serve to minimize counter-regulatory mechanisms that act to restore blood pressure values to pre-treatment levels.[13][128] Most people require more than one medication to control their hypertension.[110] Medications for blood pressure control should be implemented by a stepped care approach when target levels are not reached.[127]

Previously beta-blockers such as atenolol were thought to have similar beneficial effects when used as first-line therapy for hypertension. However, a Cochrane review that included 13 trials found that the effects of beta-blockers are inferior to that of other antihypertensive medications in preventing cardiovascular disease.[129]

Resistant hypertension

Resistant hypertension is defined as high blood pressure that remains above a target level, in spite of being prescribed three or more antihypertensive drugs simultaneously with different mechanisms of action.[130] Failing to take the prescribed drugs, is an important cause of resistant hypertension.[131] Resistant hypertension may also result from chronically high activity of the autonomic nervous system, an effect known as "neurogenic hypertension".[132] Electrical therapies that stimulate the baroreflex are being studied as an option for lowering blood pressure in people in this situation.[133]

Epidemiology

Map of the prevalence of hypertension in adult men in 2014.[134]

Disability-adjusted life year for hypertensive heart disease per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004.[135]

| no data <110 110-220 220-330 330-440 440-550 550-660 | 660-770 770-880 880-990 990-1100 1100–1600 >1600 |

Adults

As of 2014, approximately one billion adults or ~22% of the population of the world have hypertension.[136] It is slightly more frequent in men,[136] in those of low socioeconomic status,[6] and it becomes more common with age.[6] It is common in high, medium, and low income countries.[136][137] In 2004 rates of high blood pressure were highest in Africa, (30% for both sexes) and lowest in the Americas (18% for both sexes). Rates also vary markedly within regions with rates as low as 3.4% (men) and 6.8% (women) in rural India and as high as 68.9% (men) and 72.5% (women) in Poland.[138] Rates in Africa were about 45% in 2016.[139]

In Europe hypertension occurs in about 30-45% of people as of 2013.[12] In 1995 it was estimated that 43 million people (24% of the population) in the United States had hypertension or were taking antihypertensive medication.[140] By 2004 this had increased to 29%[141][142] and further to 32% (76 million US adults) by 2017.[7] In 2017, with the change in definitions for hypertension, 46% of people in the United States are affected.[7] African-American adults in the United States have among the highest rates of hypertension in the world at 44%.[143] It is also more common in Filipino Americans and less common in US whites and Mexican Americans.[6][144] Differences in hypertension rates are multifactorial and under study.[145]

Children

Rates of high blood pressure in children and adolescents have increased in the last 20 years in the United States.[146] Childhood hypertension, particularly in pre-adolescents, is more often secondary to an underlying disorder than in adults. Kidney disease is the most common secondary cause of hypertension in children and adolescents. Nevertheless, primary or essential hypertension accounts for most cases.[147]

Outcomes

Diagram illustrating the main complications of persistent high blood pressure

Hypertension is the most important preventable risk factor for premature death worldwide.[148] It increases the risk of ischemic heart disease,[149]strokes,[23]peripheral vascular disease,[150] and other cardiovascular diseases, including heart failure, aortic aneurysms, diffuse atherosclerosis, chronic kidney disease, atrial fibrillation, and pulmonary embolism.[11][23] Hypertension is also a risk factor for cognitive impairment and dementia.[23] Other complications include hypertensive retinopathy and hypertensive nephropathy.[27]

History

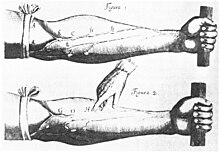

Image of veins from Harvey's Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus

Measurement

Modern understanding of the cardiovascular system began with the work of physician William Harvey (1578–1657), who described the circulation of blood in his book "De motu cordis". The English clergyman Stephen Hales made the first published measurement of blood pressure in 1733.[151][152] However, hypertension as a clinical entity came into its own with the invention of the cuff-based sphygmomanometer by Scipione Riva-Rocci in 1896.[153] This allowed easy measurement of systolic pressure in the clinic. In 1905, Nikolai Korotkoff improved the technique by describing the Korotkoff sounds that are heard when the artery is ausculated with a stethoscope while the sphygmomanometer cuff is deflated.[152] This permitted systolic and diastolic pressure to be measured.

Identification

The symptoms similar to symptoms of patients with hypertensive crisis are discussed in medieval Persian medical texts in the chapter of "fullness disease".[154] The symptoms include headache, heaviness in the head, sluggish movements, general redness and warm to touch feel of the body, prominent, distended and tense vessels, fullness of the pulse, distension of the skin, coloured and dense urine, loss of appetite, weak eyesight, impairment of thinking, yawning, drowsiness, vascular rupture, and hemorrhagic stroke.[155] Fullness disease was presumed to be due to an excessive amount of blood within the blood vessels.

Descriptions of hypertension as a disease came among others from Thomas Young in 1808 and especially Richard Bright in 1836.[151] The first report of elevated blood pressure in a person without evidence of kidney disease was made by Frederick Akbar Mahomed (1849–1884).[156]

Treatment

Historically the treatment for what was called the "hard pulse disease" consisted in reducing the quantity of blood by bloodletting or the application of leeches.[151] This was advocated by The Yellow Emperor of China, Cornelius Celsus, Galen, and Hippocrates.[151] The therapeutic approach for the treatment of hard pulse disease included changes in lifestyle (staying away from anger and sexual intercourse) and dietary program for patients (avoiding the consumption of wine, meat, and pastries, reducing the volume of food in a meal, maintaining a low-energy diet and the dietary usage of spinach and vinegar).

In the 19th and 20th centuries, before effective pharmacological treatment for hypertension became possible, three treatment modalities were used, all with numerous side-effects: strict sodium restriction (for example the rice diet[151]), sympathectomy (surgical ablation of parts of the sympathetic nervous system), and pyrogen therapy (injection of substances that caused a fever, indirectly reducing blood pressure).[151][157]

The first chemical for hypertension, sodium thiocyanate, was used in 1900 but had many side effects and was unpopular.[151] Several other agents were developed after the Second World War, the most popular and reasonably effective of which were tetramethylammonium chloride, hexamethonium, hydralazine, and reserpine (derived from the medicinal plant Rauwolfia serpentina). None of these were well tolerated.[158][159] A major breakthrough was achieved with the discovery of the first well-tolerated orally available agents. The first was chlorothiazide, the first thiazide diuretic and developed from the antibiotic sulfanilamide, which became available in 1958.[151][160] Subsequently, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and renin inhibitors were developed as antihypertensive agents.[157]

Society and culture

Awareness

Graph showing, prevalence of awareness, treatment and control of hypertension compared between the four studies of NHANES[141]

The World Health Organization has identified hypertension, or high blood pressure, as the leading cause of cardiovascular mortality.[161]The World Hypertension League (WHL), an umbrella organization of 85 national hypertension societies and leagues, recognized that more than 50% of the hypertensive population worldwide are unaware of their condition.[161] To address this problem, the WHL initiated a global awareness campaign on hypertension in 2005 and dedicated May 17 of each year as World Hypertension Day (WHD). Over the past three years, more national societies have been engaging in WHD and have been innovative in their activities to get the message to the public. In 2007, there was record participation from 47 member countries of the WHL. During the week of WHD, all these countries – in partnership with their local governments, professional societies, nongovernmental organizations and private industries – promoted hypertension awareness among the public through several media and public rallies. Using mass media such as Internet and television, the message reached more than 250 million people. As the momentum picks up year after year, the WHL is confident that almost all the estimated 1.5 billion people affected by elevated blood pressure can be reached.[162]

Economics

High blood pressure is the most common chronic medical problem prompting visits to primary health care providers in USA. The American Heart Association estimated the direct and indirect costs of high blood pressure in 2010 as $76.6 billion.[143] In the US 80% of people with hypertension are aware of their condition, 71% take some antihypertensive medication, but only 48% of people aware that they have hypertension adequately control it.[143] Adequate management of hypertension can be hampered by inadequacies in the diagnosis, treatment, or control of high blood pressure.[163]Health care providers face many obstacles to achieving blood pressure control, including resistance to taking multiple medications to reach blood pressure goals. People also face the challenges of adhering to medicine schedules and making lifestyle changes. Nonetheless, the achievement of blood pressure goals is possible, and most importantly, lowering blood pressure significantly reduces the risk of death due to heart disease and stroke, the development of other debilitating conditions, and the cost associated with advanced medical care.[164][165]

Research

A 2015 review of several studies found that restoring blood vitamin D levels by using supplements (more than 1,000 IU per day) reduced blood pressure in hypertensive individuals when they had existing vitamin D deficiency.[166] The results also demonstrated a correlation of chronically low vitamin D levels with a higher chance of becoming hypertensive. Supplementation with vitamin D over 18 months in normotensive individuals with vitamin D deficiency did not significantly affect blood pressure.[166]

There is tentative evidence that an increased calcium intake may help in preventing hypertension. However, more studies are needed to assess the optimal dose and the possible side effects.[167]

Other animals

Cats

Hypertension in cats is indicated with a systolic blood pressure greater than 150 mm Hg, with amlodipine the usual first-line treatment.[168]

Dogs

Normal blood pressure can differ substantially between breeds but hypertension in dogs is often diagnosed if systolic blood pressure is above 160 mm Hg particularly if this is associated with target organ damage.[169] Inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system and calcium channel blockers are often used to treat hypertension in dogs, although other drugs may be indicated for specific conditions causing high blood pressure.[169]

References

^ abcde "High Blood Pressure Fact Sheet". CDC. 19 February 2015. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab Lackland, DT; Weber, MA (May 2015). "Global burden of cardiovascular disease and stroke: hypertension at the core". The Canadian journal of cardiology. 31 (5): 569–71. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2015.01.009. PMID 25795106.

^ ab Mendis, Shanthi; Puska, Pekka; Norrving, Bo (2011). Global atlas on cardiovascular disease prevention and control (PDF) (1st ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization in collaboration with the World Heart Federation and the World Stroke Organization. p. 38. ISBN 9789241564373. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 August 2014.

^ ab Hernandorena, I; Duron, E; Vidal, JS; Hanon, O (July 2017). "Treatment options and considerations for hypertensive patients to prevent dementia". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy (Review). 18 (10): 989–1000. doi:10.1080/14656566.2017.1333599. PMID 28532183.

^ abcdefghijklmn Poulter, NR; Prabhakaran, D; Caulfield, M (22 August 2015). "Hypertension". Lancet. 386 (9995): 801–12. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61468-9. PMID 25832858.

^ abcdef Carretero OA, Oparil S; Oparil (January 2000). "Essential hypertension. Part I: definition and etiology". Circulation. 101 (3): 329–35. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.101.3.329. PMID 10645931. Archived from the original on 12 February 2012.

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstu Paul Whelton; et al. (13 November 2017). "2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults" (PDF). Hypertension: HYP.0000000000000065. doi:10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065. PMID 29133356.CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al. (link)

^ abc "How Is High Blood Pressure Treated?". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. 10 September 2015. Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

^ ab Campbell, NR; Lackland, DT; Lisheng, L; Niebylski, ML; Nilsson, PM; Zhang, XH (March 2015). "Using the Global Burden of Disease study to assist development of nation-specific fact sheets to promote prevention and control of hypertension and reduction in dietary salt: a resource from the World Hypertension League". Journal of clinical hypertension (Greenwich, Conn.). 17 (3): 165–67. doi:10.1111/jch.12479. PMID 25644474.

^ ab Naish, Jeannette; Court, Denise Syndercombe (2014). Medical sciences (2 ed.). p. 562. ISBN 9780702052491. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016.

^ ab Lau, DH; Nattel, S; Kalman, JM; Sanders, P (August 2017). "Modifiable Risk Factors and Atrial Fibrillation". Circulation (Review). 136 (6): 583–96. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023163. PMID 28784826.

^ abc Giuseppe, Mancia; Fagard, R; Narkiewicz, K; Redon, J; Zanchetti, A; Bohm, M; Christiaens, T; Cifkova, R; De Backer, G; Dominiczak, A; Galderisi, M; Grobbee, DE; Jaarsma, T; Kirchhof, P; Kjeldsen, SE; Laurent, S; Manolis, AJ; Nilsson, PM; Ruilope, LM; Schmieder, RE; Sirnes, PA; Sleight, P; Viigimaa, M; Waeber, B; Zannad, F; Redon, J; Dominiczak, A; Narkiewicz, K; Nilsson, PM; et al. (July 2013). "2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)". European Heart Journal. 34 (28): 2159–219. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht151. PMID 23771844.

^ abcdef James, PA.; Oparil, S.; Carter, BL.; Cushman, WC.; Dennison-Himmelfarb, C.; Handler, J.; Lackland, DT.; Lefevre, ML.; et al. (Dec 2013). "2014 Evidence-Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Report From the Panel Members Appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8)". JAMA. 311 (5): 507–20. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427. PMID 24352797.

^ Musini, VM; Tejani, AM; Bassett, K; Wright, JM (7 October 2009). "Pharmacotherapy for hypertension in the elderly". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD000028. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000028.pub2. PMID 19821263.

^ Sundström, Johan; Arima, Hisatomi; Jackson, Rod; Turnbull, Fiona; Rahimi, Kazem; Chalmers, John; Woodward, Mark; Neal, Bruce (February 2015). "Effects of Blood Pressure Reduction in Mild Hypertension". Annals of Internal Medicine. 162: 184–91. doi:10.7326/M14-0773. PMID 25531552.

^ Xie, X; Atkins, E; Lv, J; Bennett, A; Neal, B; Ninomiya, T; Woodward, M; MacMahon, S; Turnbull, F; Hillis, GS; Chalmers, J; Mant, J; Salam, A; Rahimi, K; Perkovic, V; Rodgers, A (30 January 2016). "Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering on cardiovascular and renal outcomes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet. 387 (10017): 435–43. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00805-3. PMID 26559744.

^ Diao, D; Wright, JM; Cundiff, DK; Gueyffier, F (Aug 15, 2012). "Pharmacotherapy for mild hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8: CD006742. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006742.pub2. PMID 22895954.

^ Garrison, SR; Kolber, MR; Korownyk, CS; McCracken, RK; Heran, BS; Allan, GM (8 August 2017). "Blood pressure targets for hypertension in older adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8: CD011575. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011575.pub2. PMID 28787537.

^ Musini, VM; Gueyffier, F; Puil, L; Salzwedel, DM; Wright, JM (16 August 2017). "Pharmacotherapy for hypertension in adults aged 18 to 59 years". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8: CD008276. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008276.pub2. PMID 28813123.

^ ab Fisher ND, Williams GH (2005). "Hypertensive vascular disease". In Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, et al. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (16th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. pp. 1463–81. ISBN 0-07-139140-1.

^ Marshall, IJ; Wolfe, CD; McKevitt, C (Jul 9, 2012). "Lay perspectives on hypertension and drug adherence: systematic review of qualitative research". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 345: e3953. doi:10.1136/bmj.e3953. PMC 3392078. PMID 22777025.

^ ab Wong T, Mitchell P; Mitchell (February 2007). "The eye in hypertension". Lancet. 369 (9559): 425–35. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60198-6. PMID 17276782.

^ abcdefghijklmn O'Brien, Eoin; Beevers, D. G.; Lip, Gregory Y. H. (2007). ABC of hypertension. London: BMJ Books. ISBN 1-4051-3061-X.

^ Rodriguez, Maria Alexandra; Kumar, Siva K.; De Caro, Matthew (2010-04-01). "Hypertensive crisis". Cardiology in Review. 18 (2): 102–07. doi:10.1097/CRD.0b013e3181c307b7. ISSN 1538-4683. PMID 20160537.

^ "Hypertensive Crisis". www.heart.org. Archived from the original on 25 July 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

^ abc Marik PE, Varon J; Varon (June 2007). "Hypertensive crises: challenges and management". Chest. 131 (6): 1949–62. doi:10.1378/chest.06-2490. PMID 17565029. Archived from the original on 2012-12-04.

^ abcdef Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo Jr. JL, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright Jr. JT, Roccella EJ, et al. (December 2003). "Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure". Hypertension. Joint National Committee On Prevention. 42 (6): 1206–52. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. PMID 14656957. Archived from the original on 20 May 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

^ ab Perez, MI; Musini, VM; Wright, James M (23 January 2008). "Pharmacological interventions for hypertensive emergencies". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD003653. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003653.pub3. PMID 18254026.

^ Harrison's principles of internal medicine (18th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. 2011. pp. 55–61. ISBN 9780071748896.

^ ab "Management of hypertension in pregnant and postpartum women". www.uptodate.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

^ Gibson, Paul (30 July 2009). "Hypertension and Pregnancy". eMedicine Obstetrics and Gynecology. Medscape. Archived from the original on 24 July 2009. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

^ ab Rodriguez-Cruz, Edwin; Ettinger, Leigh M (6 April 2010). "Hypertension". eMedicine Pediatrics: Cardiac Disease and Critical Care Medicine. Medscape. Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

^ abc Dionne JM, Abitbol CL, Flynn JT (January 2012). "Hypertension in infancy: diagnosis, management and outcome". Pediatr. Nephrol. 27 (1): 17–32. doi:10.1007/s00467-010-1755-z. PMID 21258818.

^ Ehret GB, Munroe PB, Rice KM, et al. (October 2011). "Genetic variants in novel pathways influence blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk". Nature. 478 (7367): 103–09. doi:10.1038/nature10405. PMC 3340926. PMID 21909115.

^ Lifton RP, Gharavi AG, Geller DS (2001-02-23). "Molecular mechanisms of human hypertension". Cell. 104 (4): 545–56. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00241-0. PMID 11239411.

^ ab Kato, Norihiro; Loh, Marie; Takeuchi, Fumihiko; Verweij, Niek; Wang, Xu; Zhang, Weihua; Kelly, Tanika N.; Saleheen, Danish; Lehne, Benjamin (2015-11-01). "Trans-ancestry genome-wide association study identifies 12 genetic loci influencing blood pressure and implicates a role for DNA methylation". Nature Genetics. 47 (11): 1282–93. doi:10.1038/ng.3405. ISSN 1546-1718. PMC 4719169. PMID 26390057.

^ Vasan, RS; Beiser, A; Seshadri, S; Larson, MG; Kannel, WB; D'Agostino, RB; Levy, D (2002-02-27). "Residual lifetime risk for developing hypertension in middle-aged women and men: The Framingham Heart Study". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 287 (8): 1003–10. doi:10.1001/jama.287.8.1003. PMID 11866648.

^ Meng, L; Chen, D; Yang, Y; Zheng, Y; Hui, R (May 2012). "Depression increases the risk of hypertension incidence: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies". Journal of Hypertension. 30 (5): 842–51. doi:10.1097/hjh.0b013e32835080b7. PMID 22343537.

^ Mesas, AE; Leon-Muñoz, LM; Rodriguez-Artalejo, F; Lopez-Garcia, E (October 2011). "The effect of coffee on blood pressure and cardiovascular disease in hypertensive individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 94 (4): 1113–26. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.016667. PMID 21880846.

^ Vaidya A, Forman JP; Forman (November 2010). "Vitamin D and hypertension: current evidence and future directions". Hypertension. 56 (5): 774–79. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.140160. PMID 20937970.

^ Sorof J, Daniels S; Daniels (October 2002). "Obesity hypertension in children: a problem of epidemic proportions". Hypertension. 40 (4): 441–47. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000032940.33466.12. PMID 12364344. Archived from the original on 2012-12-05. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

^ DiNicolantonio, James J.; Mehta, Varshil; O'Keefe, James H. (August 2017). "Is Salt a Culprit or an Innocent Bystander in Hypertension? A Hypothesis Challenging the Ancient Paradigm". The American Journal of Medicine. 130 (8): 893–899. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.03.011. ISSN 1555-7162. PMID 28373112.

^ Lawlor, DA; Smith, GD (May 2005). "Early life determinants of adult blood pressure". Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 14 (3): 259–64. doi:10.1097/01.mnh.0000165893.13620.2b. PMID 15821420.

^ Gois, PH; Souza, ER (31 January 2013). "Pharmacotherapy for hyperuricemia in hypertensive patients". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD008652. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008652.pub2. PMID 23440832.

^ Fares, A (June 2013). "Winter Hypertension: Potential mechanisms". International journal of health sciences. 7 (2): 210–9. doi:10.12816/0006044. PMC 3883610. PMID 24421749.

^ Dluhy RG, Williams GH (1998). "Endocrine hypertension". In Wilson JD, Foster DW, Kronenberg HM. Williams textbook of endocrinology (9th ed.). Philadelphia ; Montreal: W.B. Saunders. pp. 729–49. ISBN 0721661521.

^ Grossman E, Messerli FH; Messerli (January 2012). "Drug-induced Hypertension: An Unappreciated Cause of Secondary Hypertension". Am. J. Med. 125 (1): 14–22. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.05.024. PMID 22195528.

^ Jieying Jiang; Mengling Liu; Faruque Parvez; et al. (August 2015). "Association between Arsenic Exposure from Drinking Water and Longitudinal Change in Blood Pressure among HEALS Cohort Participants". Environmental Health Perspectives. 123 (8). doi:10.1289/ehp.1409004. PMC 4529016. PMID 25816368.

^ Abhyankar, LN; Jones, MR; Guallar, E; Navas-Acien, A (April 2012). "Arsenic exposure and hypertension: a systematic review". Environmental Health Perspectives. 120 (4): 494–500. doi:10.1289/ehp.1103988. PMC 3339454. PMID 22138666.

^ Roerecke, Michael; Tobe, Sheldon W.; Kaczorowski, Janusz; Bacon, Simon L.; Vafaei, Afshin; Hasan, Omer S. M.; Krishnan, Rohin J.; Raifu, Amidu O.; Rehm, Jürgen (27 June 2018). "Sex‐Specific Associations Between Alcohol Consumption and Incidence of Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis of Cohort Studies". Journal of the American Heart Association. 7 (13): e008202. doi:10.1161/JAHA.117.008202.

^ Conway J (April 1984). "Hemodynamic aspects of essential hypertension in humans". Physiol. Rev. 64 (2): 617–60. PMID 6369352.

^ ab Palatini P, Julius S; Julius (June 2009). "The role of cardiac autonomic function in hypertension and cardiovascular disease". Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 11 (3): 199–205. doi:10.1007/s11906-009-0035-4. PMID 19442329.

^ Andersson OK, Lingman M, Himmelmann A, Sivertsson R, Widgren BR (2004). "Prediction of future hypertension by casual blood pressure or invasive hemodynamics? A 30-year follow-up study". Blood Press. 13 (6): 350–54. doi:10.1080/08037050410004819. PMID 15771219.

^ Folkow B (April 1982). "Physiological aspects of primary hypertension". Physiol. Rev. 62 (2): 347–504. PMID 6461865.

^ Struijker Boudier HA, le Noble JL, Messing MW, Huijberts MS, le Noble FA, van Essen H (December 1992). "The microcirculation and hypertension". J Hypertens Suppl. 10 (7): S147–56. doi:10.1097/00004872-199212000-00016. PMID 1291649.

^ Schiffrin EL (February 1992). "Reactivity of small blood vessels in hypertension: relation with structural changes. State of the art lecture". Hypertension. 19 (2 Suppl): II1–9. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.19.2_Suppl.II1-a. PMID 1735561.

^ Safar ME, London GM; London (August 1987). "Arterial and venous compliance in sustained essential hypertension". Hypertension. 10 (2): 133–9. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.10.2.133. PMID 3301662.

^ Chobanian AV (August 2007). "Clinical practice. Isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly". N. Engl. J. Med. 357 (8): 789–96. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp071137. PMID 17715411.

^ Zieman SJ, Melenovsky V, Kass DA (May 2005). "Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and therapy of arterial stiffness". Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25 (5): 932–43. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000160548.78317.29. PMID 15731494.

^ Navar LG (December 2010). "Counterpoint: Activation of the intrarenal renin–angiotensin system is the dominant contributor to systemic hypertension". J. Appl. Physiol. 109 (6): 1998–2000, discussion 2015. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00182.2010a. PMC 3006411. PMID 21148349.

^ Esler M, Lambert E, Schlaich M (December 2010). "Point: Chronic activation of the sympathetic nervous system is the dominant contributor to systemic hypertension". J. Appl. Physiol. 109 (6): 1996–98. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00182.2010. PMID 20185633.

^ Versari D, Daghini E, Virdis A, Ghiadoni L, Taddei S (June 2009). "Endothelium-dependent contractions and endothelial dysfunction in human hypertension". Br. J. Pharmacol. 157 (4): 527–36. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00240.x. PMC 2707964. PMID 19630832.

^ Marchesi C, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL (July 2008). "Role of the renin–angiotensin system in vascular inflammation". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 29 (7): 367–74. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2008.05.003. PMID 18579222.

^ Gooch JL, Sharma AC (July 2014). "Targeting the immune system to treat hypertension: where are we?". Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 23 (5): 473–9. doi:10.1097/MNH.0000000000000052. PMID 25036747.

^ Adrogué, HJ; Madias, NE (10 May 2007). "Sodium and potassium in the pathogenesis of hypertension". The New England Journal of Medicine. 356 (19): 1966–78. doi:10.1056/NEJMra064486. PMID 17494929.

^ Perez, V; Chang, ET (November 2014). "Sodium-to-potassium ratio and blood pressure, hypertension, and related factors". Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.). 5 (6): 712–41. doi:10.3945/an.114.006783. PMC 4224208. PMID 25398734.

^ Loscalzo, Joseph; Fauci, Anthony S.; Braunwald, Eugene; Dennis L. Kasper; Hauser, Stephen L; Longo, Dan L. (2008). Harrison's principles of internal medicine. McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 0-07-147691-1.

^ Padwal RS, Hemmelgarn BR, Khan NA, et al. (May 2009). "The 2009 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part 1 – blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk". Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 25 (5): 279–86. doi:10.1016/S0828-282X(09)70491-X. PMC 2707176. PMID 19417858.

^ Padwal RJ, Hemmelgarn BR, Khan NA, et al. (June 2008). "The 2008 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part 1 – blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk". Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 24 (6): 455–63. doi:10.1016/S0828-282X(08)70619-6. PMC 2643189. PMID 18548142.

^ Padwal RS, Hemmelgarn BR, McAlister FA, et al. (May 2007). "The 2007 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part 1 – blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk". Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 23 (7): 529–38. doi:10.1016/S0828-282X(07)70797-3. PMC 2650756. PMID 17534459.

^ Hemmelgarn BR, McAlister FA, Grover S, et al. (May 2006). "The 2006 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part I – Blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk". Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 22 (7): 573–81. doi:10.1016/S0828-282X(06)70279-3. PMC 2560864. PMID 16755312.

^ Hemmelgarn BR, McAllister FA, Myers MG, et al. (June 2005). "The 2005 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: part 1- blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk". Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 21 (8): 645–56. PMID 16003448.

^ Aronow WS, Fleg JL, Pepine CJ, Artinian NT, Bakris G, Brown AS, Ferdinand KC, Ann Forciea M, Frishman WH, Jaigobin C, Kostis JB, Mancia G, Oparil S, Ortiz E, Reisin E, Rich MW, Schocken DD, Weber MA, Wesley DJ, Harrington RA, Bates ER, Bhatt DL, Bridges CR, Eisenberg MJ, Ferrari VA, Fisher JD, Gardner TJ, Gentile F, Gilson MF, Hlatky MA, Jacobs AK, Kaul S, Moliterno DJ, Mukherjee D, Rosenson RS, Stein JH, Weitz HH, Wesley DJ (2011). "ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology, American Geriatrics Society, American Society for Preventive Cardiology, American Society of Hypertension, American Society of Nephrology, Association of Black Cardiologists, and European Society of Hypertension". J Am Soc Hypertens. 5 (4): 259–352. doi:10.1016/j.jash.2011.06.001. PMID 21771565.

^ "Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management | Guidance and guidelines | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. Retrieved 2018-11-11.

^ abcdefgh Viera, AJ (July 2017). "Screening for Hypertension and Lowering Blood Pressure for Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Events". The Medical Clinics of North America (Review). 101 (4): 701–12. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2017.03.003. PMID 28577621.

^ abc Vischer, AS; Burkard, T (2017). "Principles of Blood Pressure Measurement - Current Techniques, Office vs Ambulatory Blood Pressure Measurement". Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology (Review). 956: 85–96. doi:10.1007/5584_2016_49. PMID 27417699.

^ Siu, AL (13 October 2015). "Screening for High Blood Pressure in Adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". Annals of Internal Medicine. 163: 778–86. doi:10.7326/m15-2223. PMID 26458123.

^ abc National Clinical Guidance Centre (August 2011). "7 Diagnosis of Hypertension, 7.5 Link from evidence to recommendations". Hypertension (NICE CG 127) (PDF). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. p. 102. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

^ Siu, AL; U.S. Preventive Services Task, Force (17 November 2015). "Screening for High Blood Pressure in Adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". Annals of Internal Medicine. 163 (10): 778–86. doi:10.7326/m15-2223. PMID 26458123.

^ Franklin, SS; Wilkinson, IB; McEniery, CM (February 2012). "Unusual hypertensive phenotypes: what is their significance?". Hypertension. 59 (2): 173–78. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.182956. PMID 22184330.

^ Kario, K (Jun 2009). "Orthostatic hypertension: a measure of blood pressure variation for predicting cardiovascular risk". Circulation Journal. 73 (6): 1002–07. doi:10.1253/circj.cj-09-0286. PMID 19430163.

^ Luma GB, Spiotta RT; Spiotta (May 2006). "Hypertension in children and adolescents". Am Fam Physician. 73 (9): 1558–68. PMID 16719248.

^ abcdefgh "Guideline for the diagnosis and management of hypertension in adults" (PDF). Heart Foundation. 2016. p. 12. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

^ ab Crawford, Chris (12 December 2017). "AAFP Decides to Not Endorse AHA/ACC Hypertension Guideline". AAFP. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

^ ab Mancia G; De Backer G; Dominiczak A; et al. (September 2007). "2007 ESH-ESC Practice Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension: ESH-ESC Task Force on the Management of Arterial Hypertension". J. Hypertens. 25 (9): 1751–62. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282f0580f. PMID 17762635.

^ abcde Williams B, Poulter NR, Brown MJ, Davis M, McInnes GT, Potter JF, Sever PS, McG Thom S (March 2004). "Guidelines for management of hypertension: report of the fourth working party of the British Hypertension Society, 2004-BHS IV". Journal of Human Hypertension. 18 (3): 139–85. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1001683. PMID 14973512.

^ "2017 Guideline for High Blood Pressure in Adults - American College of Cardiology". American College of Cardiology. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

^ abcde National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents (August 2004). "The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents". Pediatrics. 114 (2 Suppl 4th Report): 555–76. doi:10.1542/peds.114.2.S2.555. PMID 15286277.

^ Chiolero, A; Bovet, P; Paradis, G (Mar 1, 2013). "Screening for elevated blood pressure in children and adolescents: a critical appraisal". JAMA Pediatrics. 167 (3): 266–73. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.438. PMID 23303490.

^ Daniels, SR.; Gidding, SS. (Mar 2013). "Blood pressure screening in children and adolescents: is the glass half empty or more than half full?". JAMA Pediatr. 167 (3): 302–04. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.439. PMID 23303514.

^ Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Dec 2011). "Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents: summary report". Pediatrics. 128 Suppl 5: S213–56. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2107C. PMC 4536582. PMID 22084329.

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2013.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ Moyer, VA.; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (October 2013). "Screening for Primary Hypertension in Children and Adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement*". Annals of Internal Medicine. 159 (9): 613–19. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-9-201311050-00725. PMID 24097285.

^ Whelton PK, et al. (2002). "Primary prevention of hypertension. Clinical and public health advisory from the National High Blood Pressure Education Program". JAMA. 288 (15): 1882–88. doi:10.1001/jama.288.15.1882. PMID 12377087.

^ ab "Evidence-based policy for salt reduction is needed". Lancet. 388 (10043): 438. 30 July 2016. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31205-3. PMID 27507743.

^ Mente, Andrew; O'Donnell, Martin; Rangarajan, Sumathy; Dagenais, Gilles; Lear, Scott; McQueen, Matthew; Diaz, Rafael; Avezum, Alvaro; Lopez-Jaramillo, Patricio; Lanas, Fernando; Li, Wei; Lu, Yin; Yi, Sun; Rensheng, Lei; Iqbal, Romaina; Mony, Prem; Yusuf, Rita; Yusoff, Khalid; Szuba, Andrzej; Oguz, Aytekin; Rosengren, Annika; Bahonar, Ahmad; Yusufali, Afzalhussein; Schutte, Aletta Elisabeth; Chifamba, Jephat; Mann, Johannes F E; Anand, Sonia S; Teo, Koon; Yusuf, S (July 2016). "Associations of urinary sodium excretion with cardiovascular events in individuals with and without hypertension: a pooled analysis of data from four studies". The Lancet. 388 (10043): 465–75. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30467-6. PMID 27216139.

^ Law M, Wald N, Morris J (2003). "Lowering blood pressure to prevent myocardial infarction and stroke: a new preventive strategy". Health Technol Assess. 7 (31): 1–94. doi:10.3310/hta7310. PMID 14604498.

^ abc Members, Authors/Task Force; Mancia, Giuseppe; Fagard, Robert; Narkiewicz, Krzysztof; Redon, Josep; Zanchetti, Alberto; Böhm, Michael; Christiaens, Thierry; Cifkova, Renata (13 June 2013). "2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension". European Heart Journal. 34 (28): 2159–219. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht151. hdl:1854/LU-4127523. ISSN 0195-668X. PMID 23771844. Archived from the original on 27 January 2015.

^ ab Daskalopoulou, Stella S.; Rabi, Doreen M.; Zarnke, Kelly B.; Dasgupta, Kaberi; Nerenberg, Kara; Cloutier, Lyne; Gelfer, Mark; Lamarre-Cliche, Maxime; Milot, Alain (2015-01-01). "The 2015 Canadian Hypertension Education Program Recommendations for Blood Pressure Measurement, Diagnosis, Assessment of Risk, Prevention, and Treatment of Hypertension". Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 31 (5): 549–68. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2015.02.016. PMID 25936483.

^ ab "Hypertension | 1-recommendations | Guidance and guidelines | NICE". http://www.nice.org.uk. Retrieved 2015-08-04.

^ Arguedas, JA; Perez, MI; Wright, JM (8 July 2009). "Treatment blood pressure targets for hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD004349. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004349.pub2. PMID 19588353.

^ ab Arguedas, JA; Leiva, V; Wright, JM (Oct 30, 2013). "Blood pressure targets for hypertension in people with diabetes mellitus". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10): CD008277. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008277.pub2. PMID 24170669.

^ Saiz, Luis Carlos; Gorricho, Javier; Garjón, Javier; Celaya, Mª Concepción; Muruzábal, Lourdes; Malón, Mª del Mar; Montoya, Rodolfo; López, Antonio (2017-10-11). "Blood pressure targets for the treatment of people with hypertension and cardiovascular disease". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10: CD010315. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010315.pub2. PMID 29020435.

^ Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Rich R, Humphrey LL, Frost J, Forciea MA (17 January 2017). "Pharmacologic Treatment of Hypertension in Adults Aged 60 Years or Older to Higher Versus Lower Blood Pressure Targets: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 166 (6): 430–437. doi:10.7326/M16-1785. PMID 28135725.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ Qaseem, A; Wilt, TJ; Rich, R; Humphrey, LL; Frost, J; Forciea, MA; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians and the Commission on Health of the Public and Science of the American Academy of Family, Physicians. (21 March 2017). "Pharmacologic Treatment of Hypertension in Adults Aged 60 Years or Older to Higher Versus Lower Blood Pressure Targets: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 166 (6): 430–437. doi:10.7326/m16-1785. PMID 28135725.

^ Wright JT, Jr; Fine, LJ; Lackland, DT; Ogedegbe, G; Dennison Himmelfarb, CR (1 April 2014). "Evidence supporting a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 150 mm Hg in patients aged 60 years or older: the minority view". Annals of Internal Medicine. 160 (7): 499–503. doi:10.7326/m13-2981. PMID 24424788.

^ "KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Blood Pressure in Chronic Kidney Disease" (PDF). Kidney International Supplement. December 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 June 2015.

^ Brunström, Mattias; Carlberg, Bo (2016-01-30). "Lower blood pressure targets: to whom do they apply?". Lancet. 387 (10017): 405–06. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00816-8. ISSN 1474-547X. PMID 26559745.

^ Xie, Xinfang; Atkins, Emily; Lv, Jicheng; Rodgers, Anthony (2016-06-10). "Intensive blood pressure lowering – Authors' reply". The Lancet. 387 (10035): 2291. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30366-X. PMID 27302266.

^ ab Go, AS; Bauman, M; King, SM; Fonarow, GC; Lawrence, W; Williams, KA; Sanchez, E (15 November 2013). "An Effective Approach to High Blood Pressure Control: A Science Advisory From the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention". Hypertension. 63 (4): 878–85. doi:10.1161/HYP.0000000000000003. PMID 24243703. Archived from the original on 20 November 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

^ ab Semlitsch, T; Jeitler, K; Berghold, A; Horvath, K; Posch, N; Poggenburg, S; Siebenhofer, A (2 March 2016). "Long-term effects of weight-reducing diets in people with hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3: CD008274. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008274.pub3. PMID 26934541. Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

^ Aburto NJ, Ziolkovska A, Hooper L, Elliott P, Cappuccio FP, Meerpohl JJ (2013). "Effect of lower sodium intake on health: systematic review and meta-analyses". BMJ. 346: f1326. doi:10.1136/bmj.f1326. PMC 4816261. PMID 23558163.

^ He, FJ; Li, J; Macgregor, GA (April 2013). "Effect of longer-term modest salt reduction on blood pressure". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis). 30 (4): CD004937. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004937.pub2. PMID 23633321.

^ Karppanen, Heikki; Mervaala, Eero (2006-10-01). "Sodium intake and hypertension". Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. 49 (2): 59–75. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2006.07.001. ISSN 0033-0620. PMID 17046432.

^ Sacks, F. M.; Svetkey, L. P.; Vollmer, W. M.; Appel, L. J.; Bray, G. A.; Harsha, D.; Obarzanek, E.; Conlin, P. R.; Miller, E. R. (2001-01-04). "Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group". The New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (1): 3–10. doi:10.1056/NEJM200101043440101. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 11136953.

^ Yokoyama, Yoko; Nishimura, Kunihiro; Barnard, Neal D.; Takegami, Misa; Watanabe, Makoto; Sekikawa, Akira; Okamura, Tomonori; Miyamoto, Yoshihiro (2014). "Vegetarian Diets and Blood Pressure". JAMA Internal Medicine. 174 (4): 577–87. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14547. ISSN 2168-6106. PMID 24566947.

^ Hartley L, Flowers N, Holmes J, Clarke A, Stranges S, Hooper L, Rees K (June 2013). "Green and black tea for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease" (PDF). Cochrane Database Syst Rev (Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis). 6 (6): CD009934. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009934.pub2. PMID 23780706.

^ Liu G, Mi XN, Zheng XX, Xu YL, Lu J, Huang XH (October 2014). "Effects of tea intake on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". Br J Nutr (Meta-Analysis). 112 (7): 1043–54. doi:10.1017/S0007114514001731. PMID 25137341.

^ Khalesi S, Sun J, Buys N, Jamshidi A, Nikbakht-Nasrabadi E, Khosravi-Boroujeni H (September 2014). "Green tea catechins and blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". Eur J Nutr (Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis). 53 (6): 1299–1311. doi:10.1007/s00394-014-0720-1. PMID 24861099.

^ Peng X, Zhou R, Wang B, Yu X, Yang X, Liu K, Mi M (September 2014). "Effect of green tea consumption on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials". Sci Rep (Meta-Analysis). 4: 6251. doi:10.1038/srep06251. PMC 4150247. PMID 25176280.

^ Aburto, NJ; Hanson, S; Gutierrez, H; Hooper, L; Elliott, P; Cappuccio, FP (3 April 2013). "Effect of increased potassium intake on cardiovascular risk factors and disease: systematic review and meta-analyses". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 346: f1378. doi:10.1136/bmj.f1378. PMC 4816263. PMID 23558164.

^ Stone, MS; Martyn, L; Weaver, CM (22 July 2016). "Potassium Intake, Bioavailability, Hypertension, and Glucose Control". Nutrients. 8 (7): 444. doi:10.3390/nu8070444. PMID 27455317.

^ "Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee". Archived from the original on 26 April 2017. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

^ ab Brook RD, Appel LJ, Rubenfire M, Ogedegbe G, Bisognano JD, Elliott WJ, Fuchs FD, Hughes JW, Lackland DT, Staffileno BA, Townsend RR, Rajagopalan S, American Heart Association Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Council on Nutrition, Physical, Activity (Jun 2013). "Beyond medications and diet: alternative approaches to lowering blood pressure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association". Hypertension. 61 (6): 1360–83. doi:10.1161/HYP.0b013e318293645f. PMID 23608661.

^ Nagele, Eva; Jeitler, Klaus; Horvath, Karl; Semlitsch, Thomas; Posch, Nicole; Herrmann, Kirsten H.; Grouven, Ulrich; Hermanns, Tatjana; Hemkens, Lars G.; Siebenhofer, Andrea (2014). "Clinical effectiveness of stress-reduction techniques in patients with hypertension". Journal of Hypertension. 32 (10): 1936–44. doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000000298. ISSN 0263-6352. PMID 25084308.

^ Dickinson, HO; Campbell, F; Beyer, FR; Nicolson, DJ; Cook, JV; Ford, GA; Mason, JM (23 January 2008). "Relaxation therapies for the management of primary hypertension in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD004935. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004935.pub2. PMID 18254065.

^ ab Glynn, Liam G; Murphy, Andrew W; Smith, Susan M; Schroeder, Knut; Fahey, Tom (2010-03-17). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd005182.pub4.

^ Chen, JM; Heran, BS; Wright, JM (7 October 2009). "Blood pressure lowering efficacy of diuretics as second-line therapy for primary hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD007187. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007187.pub2. PMID 19821398.

^ Wiysonge, CS; Bradley, HA; Volmink, J; Mayosi, BM; Opie, LH (20 January 2017). "Beta-blockers for hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD002003. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002003.pub5. PMC 5369873. PMID 28107561.