Vicksburg, Mississippi

This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (January 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Vicksburg | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Vicksburg | |

Old Warren County Courthouse ("Old Courthouse Museum") | |

| Nickname(s): "Gibraltar of the Confederacy"[1] | |

Location of Vicksburg in Warren County | |

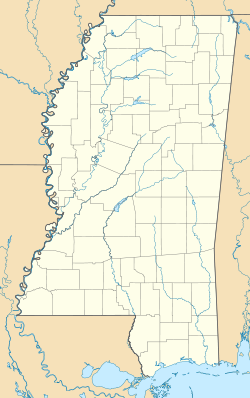

Vicksburg Location in Mississippi in the United States Show map of Mississippi  Vicksburg Vicksburg (the United States) Show map of the United States | |

| Coordinates: 32°20′10″N 90°52′31″W / 32.33611°N 90.87528°W / 32.33611; -90.87528Coordinates: 32°20′10″N 90°52′31″W / 32.33611°N 90.87528°W / 32.33611; -90.87528 | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Warren |

| Incorporated | February 15, 1839 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | George Flaggs Jr. |

| Area [2] | |

| • City | 35.06 sq mi (90.81 km2) |

| • Land | 32.98 sq mi (85.42 km2) |

| • Water | 2.08 sq mi (5.39 km2) |

| Elevation | 240 ft (82 m) |

| Population (2010)[3] | |

| • City | 23,856 |

| • Estimate (2017)[4] | 22,489 |

| • Density | 681.88/sq mi (263.27/km2) |

| • Metro | 57,433 (US: 162th) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 39180-39183 |

| Area code(s) | 601 and 769 |

| FIPS code | 28-76720 |

GNIS feature ID | 0679216 |

| Website | City of Vicksburg |

Vicksburg City Hall by famed architect J. Riely Gordon

U.S. Post Office (former) and Courthouse in Vicksburg

Vicksburg is the only city in, and county seat of, Warren County, Mississippi, United States. It is located 234 miles (377 km) northwest of New Orleans at the confluence of the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers, and 40 miles (64 km) due west of Jackson, the state capital. It is located on the east bank of the Mississippi River across from the state of Louisiana.

The city has increased in population since 1900, when 14,834 people lived here. The population was 26,407 at the 2000 census. In 2010, it was designated as the principal city of a Micropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) with a total population of 49,644. This MSA includes all of Warren County.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Political and racial unrest after the Civil War

1.2 20th century to present

1.3 Contemporary Vicksburg

2 Geography

3 Economy

4 Demographics

5 Arts and culture

5.1 Annual cultural events

5.2 Museums and other points of interest

6 Government

7 Education

7.1 High schools

7.2 Junior high schools

7.3 Elementary schools

7.4 Private schools

7.5 Former schools

8 Media

8.1 Newspaper

8.2 Radio

9 Notable people

10 Cultural references

11 Places of interest

12 See also

13 References

14 Further reading

15 External links

History

It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled History of Vicksburg, Mississippi. (Discuss) (March 2017) |

The entire Choctaw Nation's historic territory compared to the U.S. state of Mississippi.

The area which is now Vicksburg was long occupied by the Natchez Native Americans as part of their historical territory along the Mississippi. The Natchez spoke a language isolate not related to the Muskogean languages of the other major tribes in the area. Before the Natchez, other indigenous cultures had occupied this strategic area for thousands of years.

The first Europeans who settled the area were French colonists, who built Fort-Saint-Pierre in 1719 on the high bluffs overlooking the Yazoo River at present-day Redwood. They conducted fur trading with the Natchez and others and started plantations. On 29 November 1729, the Natchez attacked the fort and plantations in and around the present-day city of Natchez. They killed several hundred settlers, including the Jesuit missionary Father Paul Du Poisson. As was the custom, they took a number of women and children as captives, adopting them into their families.

The Natchez War was a disaster for French Louisiana, and the colonial population of the Natchez District never recovered. But, aided by the Choctaw, traditional enemies of the Natchez, the French defeated and scattered the Natchez and their allies, the Yazoo.

The Choctaw Nation took over the area by right of conquest and inhabited it for several decades. Under pressure from the US government, in 1801 the Choctaw agreed to cede nearly 2,000,000 acres (8,100 km2) of land to the US under the terms of the Treaty of Fort Adams. The treaty was the first of a series that eventually led to the removal in 1830 of most of the Choctaw to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River. Some Choctaw remained in Mississippi, citing article XIV of the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek; they became citizens of the state and the United States. They struggled to maintain their culture against the pressure of the binary slave society, which classified people as only white or black.

In 1790, the Spanish founded a military outpost on the site, which they called Fort Nogales (nogales meaning "walnut trees"). When the Americans took possession in 1798 following the American Revolutionary War and a treaty with Spain, they changed the name to Walnut Hills. The small village was incorporated in 1825 as Vicksburg, named after Newitt Vick, a Methodist minister who had established a Protestant mission on the site.[5]

Drawing that depicts the hanging of five gamblers in Vicksburg in 1835 among other aspects of the society of the time. From Illustrations of the American Anti-slavery Almanac for 1840.

In 1835, during the Murrell Excitement, a mob from Vicksburg attempted to expel the gamblers from the city, because the citizens were tired of the rougher element treating the city residents with nothing but contempt. They captured and hanged five gamblers who had shot and killed a local doctor.[6] The historian Joshua D. Rothman calls this event "the deadliest outbreak of extralegal violence in the slave states between the Southampton Insurrection and the Civil War."[7]

View of Vicksburg in 1855

During the American Civil War, the city finally surrendered during the Siege of Vicksburg, after which the Union Army gained control of the entire Mississippi River. The 47-day siege was intended to starve the city into submission. Its location atop a high bluff overlooking the Mississippi River proved otherwise impregnable to assault by federal troops. The surrender of Vicksburg by Confederate General John C. Pemberton on July 4, 1863, together with the defeat of General Robert E. Lee at Gettysburg the day before, has historically marked the turning point in the Civil War in the Union's favor.

From the surrender of Vicksburg until the end of the war in 1865, the area was under Union military occupation.[8] Some accounts say that the residents of Vicksburg did not celebrate the national holiday of 4th of July again until 1945, after United States victory in World War II, but this is inaccurate. Large Fourth of July celebrations were being held by 1907, and informal celebrations took place before that.[9][10]

Floating drydock in Vicksburg, circa 1905

Because of the city's location on the Mississippi River, in the 19th century it built an extensive trade from the prodigious steamboat traffic. It shipped out cotton coming to it from surrounding counties and was a major trading city.

In 1876 a Mississippi River flood cut off the large meander flowing past Vicksburg, leaving limited access to the new channel. The city's economy suffered greatly. Between 1881 and 1894, the Anchor Line, a prominent steamboat company on the Mississippi River from 1859 to 1898, operated a steamboat called the City of Vicksburg.

Political and racial unrest after the Civil War

In the first few years after the Civil War, white Confederate veterans developed the Ku Klux Klan, beginning in Tennessee; it had chapters throughout the South and attacked freedmen and their supporters. It was suppressed about 1870. By the mid-1870s, new white paramilitary groups had arisen in the Deep South, including the Red Shirts in Mississippi, as whites struggled to regain political and social power over the black majority. Elections were marked by violence and fraud as white Democrats worked to suppress black Republican voting.

In August 1874 a black sheriff, Peter Crosby, was elected in Vicksburg. Letters by a white planter, Batchelor, detail the preparations of whites for what he described as a "race war," including acquisition of the newest guns, Winchester 16 mm. On December 7, 1874, white men disrupted a black Republican meeting celebrating Crosby's victory and held him in custody before running him out of town.[11] He advised blacks from rural areas to return home; along the way, some were attacked by armed whites. During the next several days, armed white mobs swept through black areas, killing other men at home or out in the fields. Sources differ as to total fatalities, with 29–50 blacks and 2 whites reported dead at the time. Twenty-first-century historian Emilye Crosby estimates that 300 blacks were killed in the city and the surrounding area of Claiborne County, Mississippi.[12] The Red Shirts were active in Vicksburg and other Mississippi areas, and black pleas to the federal government for protection were not met.

At the request of Republican Governor Adelbert Ames, who had left the state during the violence, President Ulysses S. Grant sent Federal troops to Vicksburg in January 1875. In addition, a congressional committee investigated what was called the "Vicksburg Riot" at the time (and reported as the "Vicksburg Massacre" by northern newspapers.) They took testimony from both black and white residents, as reported by the New York Times, but no one was ever prosecuted for the deaths. The Red Shirts and other white insurgents suppressed Republican voting by both whites and blacks; smaller-scale riots were staged in the state up to the 1875 elections, at which time white Democrats regained control of a majority of seats in the state legislature.

Under new constitutions, amendments and laws passed from 1890 (Mississippi) to 1908 in the remaining southern states, white Democrats disenfranchised most blacks and many poor whites by creating barriers to voter registration, such as poll taxes, literacy tests and grandfather clauses. They passed laws imposing Jim Crow and racial segregation of public facilities.

On March 12, 1894, the popular soft drink Coca-Cola was bottled for the first time in Vicksburg by Joseph A. Biedenharn, a local confectioner. Today, surviving 19th-century Biedenharn soda bottles are prized by collectors of Coca-Cola memorabilia. The original candy store has been renovated and is used as the Biedenharn Coca-Cola Museum.

20th century to present

The historic 1894 Mississippi River Commission Building

The near exclusion of most blacks from the political system lasted for decades until after Congressional passage of civil rights legislation in the mid-1960s. Lynchings of blacks and other forms of white racial terrorism against them continued to occur in Vicksburg after the start of the 20th century. In May 1903, for instance, two black men charged with murdering a planter were taken from jail by a mob of 200 farmers and lynched before they went to trial.[13] In May of 1919, as many as a thousand white men broke down three sets of steel doors to abduct, hang, burn and shoot a black prisoner, Lloyd Clay, who was falsely accused of raping a white woman.[14][15] From 1877 to 1950 in Warren County, 14 African Americans were lynched by whites, most in the decades near the turn of the century.[16]

The United States Army Corps of Engineers diverted the Yazoo River in 1903 into the old, shallowing channel to revive the waterfront of Vicksburg. The port city was able to receive steamboats again, but much freight and passenger traffic had moved to railroads, which had become more competitive.

Railroad access to the west across the river continued to be by transfer steamers and ferry barges until a combination railroad-highway bridge was built in 1929. Vicksburg has the only crossing over the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and Memphis. It is the only highway crossing of the river between Greenville and Natchez.

After 1973, Interstate 20 bridged the river. Freight rail traffic still crosses via the old bridge. North-South transportation links are by the Mississippi River and U.S. Highway 61.

During the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, in which hundreds of thousands of acres were inundated, Vicksburg served as the primary gathering point for refugees. Relief parties put up temporary housing, as the flood submerged a large percentage of the Mississippi Delta.

Because of the overwhelming damage from the flood, the US Army Corps of Engineers established the Waterways Experiment Station as the primary hydraulics laboratory, to develop protection of important croplands and cities. Now known as the Engineer Research and Development Center, it applies military engineering, information technology, environmental engineering, hydraulic engineering, and geotechnical engineering to problems of flood control and river navigation.

In December 1953, a severe tornado swept across Vicksburg, causing 38 deaths and destroying nearly 1,000 buildings.

During World War II, cadets from the Royal Air Force, flying from their training base at Terrell, Texas, routinely flew to Vicksburg on training flights. The town served as a stand-in for the British for Cologne, Germany, which is the same distance from London, England as Vicksburg is from Terrell.[17]

Particularly after World War II, in which many blacks served, returning veterans began to be active in the civil rights movement, wanting to have full citizenship after fighting in the war. In Mississippi, activists in the Vicksburg Movement became prominent during the 1960s.

Contemporary Vicksburg

The Vicksburg Post is now located in a new building in a small shopping center off Interstate 20.

In 2001, a group of Vicksburg residents visited the Paducah, Kentucky mural project, looking for ideas for their own community development.[18] In 2002, the Vicksburg Riverfront murals program was begun by Louisiana mural artist Robert Dafford and his team on the floodwall located on the waterfront in downtown.[19] Subjects for the murals were drawn from the history of Vicksburg and the surrounding area. They include President Theodore Roosevelt's bear hunt, the Sultana, the Sprague, the Siege of Vicksburg, the Kings Crossing site, Willie Dixon, the Flood of 1927, the 1953 Vicksburg, Mississippi tornado outbreak, Rosa A. Temple High School (known for integration activism) and the Vicksburg National Military Park.[20] The project was finished in 2009 with the completion of the Jitney Jungle/Glass Kitchen mural.[19]

In the fall of 2010, a new 55-foot mural was painted on a section of wall on Grove Hill across the street from the original project by former Dafford muralists Benny Graeff and Herb Roe. The mural's subject is the annual "Run thru History" held in the Vicksburg National Military Park.[21][22]

On December 6–7, 2014, a symposium was held on the 140th anniversary of the 1874 riots. A variety of scholars gave papers and an open panel discussion was held on the second day at the Vicksburg National Military Park, in collaboration with the Jacqueline House African American Museum.[23]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 35.3 square miles (91 square kilometers), of which 32.9 sq mi (85 km2) is land and 2.4 sq mi (6.2 km2) (6.78%) is water.

Vicksburg is located at the confluence of the Mississippi River and Yazoo River. Much of the city is on top of a high bluff on the east bank of the Mississippi River.

Economy

In 2017 Emma Green of The Atlantic stated that "The Army Corps of Engineers sustains the town economically".[24]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 3,678 | — | |

| 1860 | 4,591 | 24.8% | |

| 1870 | 12,443 | 171.0% | |

| 1880 | 11,814 | −5.1% | |

| 1890 | 13,373 | 13.2% | |

| 1900 | 14,834 | 10.9% | |

| 1910 | 20,814 | 40.3% | |

| 1920 | 18,072 | −13.2% | |

| 1930 | 22,943 | 27.0% | |

| 1940 | 24,460 | 6.6% | |

| 1950 | 27,948 | 14.3% | |

| 1960 | 29,143 | 4.3% | |

| 1970 | 25,478 | −12.6% | |

| 1980 | 25,434 | −0.2% | |

| 1990 | 20,908 | −17.8% | |

| 2000 | 26,407 | 26.3% | |

| 2010 | 23,856 | −9.7% | |

| Est. 2017 | 22,489 | [4] | −5.7% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[25] 2013 Estimate[26] | |||

As of the census of 2000, there were 26,407 people with a metropolitan population of 49,644, 10,364 households, and 6,612 families residing in the city. The population density was 803.1 people per square mile (310.1/km²). There were 11,654 housing units for an average density of 354.4 per square mile (136.9/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 60.43% African American, 37.80% White, 0.15% Native American, 0.61% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 0.41% from other races, and 0.59% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.04% of the population.

There were 10,364 households out of which 32.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 34.9% were married couples living together, 24.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 36.2% were non-families. 32.0% of all households were made up of individuals and 13.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.49 and the average family size was 3.15.

In the city, the population was spread out with 28.4% under the age of 18, 9.3% from 18 to 24, 27.9% from 25 to 44, 19.6% from 45 to 64, and 14.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 82.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 77.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $28,466, and the median income for a family was $34,380. Males had a median income of $29,420 versus $20,728 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,174. About 19.3% of families and 23.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 34.8% of those under age 18 and 16.5% of those age 65 or over.

Arts and culture

Annual cultural events

Every summer, Vicksburg plays host to the Miss Mississippi Pageant and Parade. Also every summer, the Vicksburg Homecoming Benevolent Club hosts a homecoming weekend/reunion that provides scholarships to graduating high school seniors. Former residents from across the country return for the event.

Every spring and summer, Vicksburg Theatre Guild hosts Gold in the Hills, which holds the Guinness World Record for longest running show.

Museums and other points of interest

Vicksburg is home to the McRaven House, said to be "one of the most haunted houses in Mississippi".[27]

The 1902 City Hall is a Beaux-Arts Classical Revival design by the notable architect J. Riely Gordon, of San Antonio and later New York City. Gordon was responsible for 72 courthouses in his career (including Copiah County in Hazlehurst and for Wilkinson County in Woodville), for the Territorial (soon-was the State) Capitol of Arizona, as well as for Carnegie libraries, many mansions, and other buildings.[28][29]

Government

The city government consists of a mayor who is elected at-large and two aldermembers. The current mayor is George Flaggs Jr., who defeated former mayor Paul Winfield in the June 2013 election. The two aldermembers are elected from single-member districts, known as wards.

The city is home to three large US Army Corps of Engineers installations: the Engineer Research and Development Center (ERDC), which also houses the ERDC's Waterways Experiment Station; the Mississippi Valley Division headquarters; and the Vicksburg District headquarters.

The 412th Engineer Command of the US Army Reserve and the 168th Engineer Brigade of the Mississippi Army National Guard are also located in Vicksburg.

The United States Coast Guard's 8th District/Lower Mississippi River sector has an Aids To Navigation unit located in Vicksburg, operating the buoy tending vessel USCGC Kickapoo.[30]

Education

Mississippi River at Vicksburg

The City of Vicksburg is served by the Vicksburg-Warren School District.

High schools

Vicksburg High School

- 1988–1989 National Blue Ribbon School[31]

- 1988–1989 National Blue Ribbon School[31]

- Warren Central High School

Junior high schools

- Vicksburg Junior High School

- Warren Central Junior High School

- Academy of Innovation

Elementary schools

- Beechwood Elementary School

- Bovina Elementary School

- Bowmar Avenue Magnet School

- Dana Road Elementary School

- Redwood Elementary School

- Sherman Avenue Elementary School

- South Park Elementary School

- Warrenton Elementary School

- Vicksburg Intermediate School

- Warren Central Intermediate School

Private schools

- Porters Chapel Academy

- Vicksburg Catholic School- St. Francis Xavier Elementary & *Saint Aloysius Catholic High School

- Vicksburg Christian Academy

- Vicksburg Buddhist Fellowship

- Vicksburg Community School (K-12)

Former schools

- Hall's Ferry Road Elementary School

- 1985–1986, National Blue Ribbon School[31]

- 1985–1986, National Blue Ribbon School[31]

- Culkin Elementary School

- Jett Elementary School

- Cedars Elementary School

- Vicksburg Middle School

- All Saints' Episcopal School was a local boarding school located on Confederate Avenue, which closed in 2006 after 98 years in operation. The historic campus is currently used by Americorps as a regional training center.

- St. Mary's Catholic School served the African-American community.

- McIntyre Elementary School served the African-American community.

- Magnolia Avenue School serviced the African-American community and was renamed Bowman High School to honor a former principal.

- Rosa A. Temple High School served the African-American community.

- King's Elementary School served the African-American community.

- Carr Central High School.

- J.H. Culkin Academy (grades 1-12 until 1965, thereafter Culkin Elementary School).

- H.V. Cooper High School. First graduating class 1959.

- Jefferson Davis School.

- Oak Ridge School.

- Eliza Fox School (a.k.a. Grove Street School).

All Saints' College. An Episcopal college for white women. Opened in 1908 and closed in 1962.

Media

Newspaper

The Vicksburg Post, formerly the Vicksburg Evening Post, is a family-owned daily paper. It operates in facilities in a shopping center off I-20.

Radio

AM Station

| Channel | Callsign | Format | Owner |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1420 | WQBC | News/Talk | |

| 1490 | WVBG | News/Talk |

FM Station

| Channel | Callsign | Format | Owner |

|---|---|---|---|

| 89.3 | WATU | Religious | |

| 92.7 | KSBU | Urban Adult Contemporary | |

| 97.5 | KTJZ | Urban Oldies | |

| 101.3 | WBBV | Country | |

| 102.3 | WDON | Variety | |

| 104.5 | KLSM | Hot Adult Contemporary | |

| 105.5 | WVBG | Classic Hits |

Notable people

William Wirt Adams, Confederate Army officer and member of the Mississippi House of Representatives[32]

Katherine Bailess, actress, singer and dancer

Edwin C. Bearss, historian

Joseph A. Biedenharn (1866–1952), entrepreneur: first bottled Coca-Cola in 1894 at a location in Vicksburg[33]

Johnny Brewer, football player

Roosevelt Brown, former Major League Baseball outfielder for the Chicago Cubs

William Denis Brown, III, lawyer, businessman, state senator from Monroe, Louisiana; born in Vicksburg in 1931[34]

Ellis Burks, former MLB outfielder

Charles Burnett, filmmaker

Malcolm Butler, cornerback for the New England Patriots and Tennessee Titans

Jack Christian, businessman; mayor-president of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, from 1957 to 1964, was born in Vicksburg in 1911

Odia Coates, pop singer

Rod Coleman, defensive tackle for the Atlanta Falcons

Mart Crowley, playwright, TV executive

Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America (previously U.S. Congressman, Senator, Secretary of War)

Bobby DeLaughter, Mississippi state judge and prosecutor

Willie Dixon, blues bassist, singer, songwriter, and producer

John "Kayo" Dottley, college All-American and professional football player

Myrlie Evers-Williams, civil rights activist and journalist

Mark Gray, country music singer, born in Vicksburg in 1952

Louis Green, linebacker for the Denver Broncos

Milt Hinton, jazz bassist

Jay Hopson, football head coach, Southern Mississippi

Joseph Holt, longest-serving Judge Advocate General of the Army

Delbert Hosemann, Jr., MS Secretary of State

Hank Jones, jazz pianist, born in Vicksburg

Martin F. Jue amateur radio products inventor, entrepreneur[35]

Patrick Kelly, fashion designer

Brad Leggett, football player, Seattle Seahawks center[36]

George McConnell, former guitarist for Widespread Panic, Kudzu Kings, and Beanland

William Michael Morgan, country music singer

Michael Myers, defensive tackle for the Cincinnati Bengals

Key Pittman, U.S. Senator of Nevada from 1913–40; born in Vicksburg

Vail M. Pittman, 19th Governor of Nevada[37]

Evelyn Preer, African-American film actress

George Reed, former running back for the Saskatchewan Roughriders, CFL Hall of Fame member

Beah Richards, African-American film and television actress

Roy C. Strickland, businessman and politician in Louisiana and Texas, born in Vicksburg in 1942

Taylor Tankersley, Florida Marlins relief pitcher

John Thomas, former MLB player (Colorado Rockies, New York Mets, Texas Rangers, Atlanta Braves, Kansas City Royals)[38]

Jan-Michael Vincent, actor in the CBS-TV Airwolf'

Mary T. Washington, the first African-American woman CPA

Carl Westcott, entrepreneur, founder of 1-800-Flowers and Westcott Communications

Nanette Workman, singer-songwriter, actress, and author; honored by Gov. Haley Barbour at the opening of The Nanette Workman French (Francophone) House

Delmon Young, outfielder for the Philadelphia Phillies

Dmitri Young, first baseman for the Washington Nationals

Jaelyn Young, pleaded guilty to charges relating to her attempts to join ISIS[39]

Cultural references

- Vicksburg is mentioned in the Pulitzer Prize winning play Crimes of the Heart by Beth Henley.

- Several delta blues songs mention Vicksburg, for instance Charley Patton's "High Water Everywhere" and Robert Johnson's "Traveling Riverside Blues"

- The city is mentioned multiple times in the series of books surrounding the Logan family, including Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry (1976) and Let The Circle Be Unbroken (1981), by Mildred Taylor.

- A made-for-TV movie version of I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, based on Maya Angelou's memoir, was filmed in Vicksburg.

O Brother, Where Art Thou? was filmed in Vicksburg. The Stokes campaign dinner was filmed in the Southern Cultural Heritage Center's auditorium.- The hospital stairway scene from Mississippi Burning was filmed in the Southern Cultural Heritage Convent (with Gene Hackman and Willem Dafoe).

- Vicksburg is featured in Robert A. Heinlein's 1982 science fiction novel Friday as a town in the Lone Star Republic, a leading smugglers' port between Texas and the Chicago Imperium. The book's protagonist Friday Baldwin stayed there, particularly in the riverfront Lowtown, while trying to find a way into the Imperium.

- In the novel Underground to Canada the protagonists Julilly and Liza are slaves on a cotton plantation near Vicksburg.

- Vicksburg was the focus of four episodes of the American television series Ghost Adventures during Season 19, with one episode dedicated to Champion Hill Battlefield.

- Vicksburg is mentioned in the song Mississippi Queen by American rock band Mountain.

Places of interest

- Anchuca Mansion

- Balfour House

- Biedenharn Coca-Cola Museum

- Catfish Row Art Park

- Cedar Grove - The Old Klein Home

- The Jacqueline House African American Museum

- Lower Mississippi River Museum and Riverfront Interpretive Site

- McRaven House

- Old Court House Museum

- Southern Cultural Heritage Center

- Vicksburg Battlefield Museum

Vicksburg National Military Park

- Pemberton's Headquarters

- U.S.S. Cairo Gunboat & Museum

- Vicksburg Riverfront Murals

- Vicksburg Theatre Guild

- Southern Region AmeriCorps Campus

See also

References

^ "Profile for Vicksburg, Mississippi, MS". Epodunk.com. Retrieved October 6, 2012..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "2017 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved Jan 6, 2019.

^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2014-07-28.

^ ab "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

^ Picturesque Vicksburg and the Delta. Warren County-Vicksburg Public Library, Vicksburg, Mississippi: Vicksburg Foundation for Historic Preservation. 1895 [1895]. p. 11.

^ "THE VICKSBURG FLATBOAT WAR OF 1838 AND ITS INFLUENCE ON SUBMERGED LANDS LAW IN MISSISSIPPI". Masglp.olemiss.edu. Retrieved 2014-06-13.

^ Rothman, Joshua D. (1 November 2012). Flush Times and Fever Dreams: A Story of Capitalism and Slavery in the Age of Jackson. University of Georgia Press. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-8203-3326-7.

^ Cotton, Gordon; Mason, Ralph (1991). With Malice Toward Some : The Military Occupation of Vicksburg, 1864 - 1865. Vicksburg and Warren County Historical Society.

^ Waldrep, Christopher (2005). Vicksburg's Long Shadow: The Civil War Legacy Of Race And Remembrance. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 247. ISBN 978-0742548688.

^ Historian Michael G. Ballard, in his Vicksburg campaign history, pp. 420-21, claims that this story has little foundation in fact. Although it is unknown whether city officials sanctioned the day as a local holiday, Southern observances of July 4 were for many years characterized more by family picnics than by formal city or county activities.

^ A Nation under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration by Steven Hahn, Harvard University Press, 2005

^ Emilye Crosby, Little Taste of Freedom: The Black Freedom Struggle in Claiborne County, Mississippi, Univ of North Carolina Press, 2006, p. 3

^ "Lynched for Murder…". New York Times. May 4, 1903.

^ "Mob uses Rope, to Lynch Negro". Atlanta Constitution. 15 May 1919.

^ McWhirter, Cameron (2011). Red Summer The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America. Henry Holt and Company. p. 51. ISBN 9780805089066.

^ "Lynching in America, 3rd edition, 2017; SUPPLEMENT: Lynchings by County, p. 7" (PDF). Eji.org. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

^ AT6 Monument

^ "It Took A Community To Raise A Mural!", Vicksburg Riverfront Murals

^ ab "Celebrating Vicksburg: A Great American Community", Vicksburg Riverfront Murals

^ "Vicksburg Riverfront Murals". Riverfrontmurals.com. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

^ "081110". Issuu.com. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

^ "101310". Issuu.com. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

^ "140th Anniversary Vicksburg Riots Symposium", Press release, 6 November 2014, National Park Service, accessed 15 June 2015

^ Green, Emma (2017-05-01). "How Two Mississippi College Students Fell in Love and Decided to Join a Terrorist Group". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2017-07-01.

^ "Census of Population and Housing". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

^ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2014-07-30.

^ "Hauntings". Archived from the original on 2013-01-11. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

^ "James Riely Gordon: An Inventory of his Drawings and Papers, ca. 1890-1937". Lib.utexas.edu. Retrieved 2014-06-13.

^ "Two New Books For Your Architectural Library « Preservation in Mississippi". Misspreservation.com. 2011-10-05. Retrieved 2014-06-13.

^ "Sector Lower Mississippi River Organization". Uscg.mil. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

^ ab "Blue Ribbon Schools Program: Schools Recognized 1982–1983 Through 1999–2002" (PDF). Ed.gov. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

^ Who Was Who in America, Historical Volume, 1607-1896. Chicago: Marquis Who's Who. 1963.

^ "Scott Rogers, "Family imprint seen in Monroe a century after arrival", April 21, 2013". Monroe News-Star. Archived from the original on October 25, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

^ "William Denis Brown, III". Monroe News-Star, March 9, 2012. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

^ Coy, Steve (27 March 2012). "How I Started MFJ and Its Very Early Days". Retrieved 19 May 2016.

^ "Brad Leggett". DatabaseFootball.com. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

^ "Nevada Governor Vail Montgomery Pittman". National Governors Association. Retrieved October 6, 2012.

^ "John Thomson Stats". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

^ Green, Emma (2017-05-01). "How Two Mississippi College Students Fell in Love and Decided to Join a Terrorist Group". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2017-09-15.

Further reading

- Rothman, Joshua D.: Flush Times and Fever Dreams: A Story of Capitalism and Slavery in the Age of Jackson. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "article name needed". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "article name needed". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- Cox, James L. The Mississippi Almanac. (2001).

ISBN 0-9643545-2-7. - History of Vicksburg's Jewish community

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vicksburg, Mississippi. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Vicksburg. |

- City of Vicksburg

- Vicksburg Chamber of Commerce

- Vicksburg Convention & Visitors Bureau

- Warren County-Vicksburg Public Library

The Vicksburg Post, local daily newspaper- Vicksburg Foundation for Historic Preservation

- Southern Cultural Heritage Foundation

. The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

. The American Cyclopædia. 1879.