United Free Church of Scotland

| United Free Church of Scotland | |

|---|---|

| Classification | Protestant |

| Orientation | Calvinist |

| Polity | Presbyterian |

| Associations | majority incorporated into the Church of Scotland in 1929 |

| Region | Scotland |

| Origin | 1900 |

| Merger of | The United Presbyterian Church of Scotland and most of the Free Church of Scotland |

| Congregations | 53[1] |

| Members | 2,466[2] |

| Official website | ufcos.org.uk |

The United Free Church of Scotland (UF Church; Scottish Gaelic: An Eaglais Shaor Aonaichte, Scots: The Unitit Free Kirk o Scotland) is a Scottish Presbyterian denomination formed in 1900 by the union of the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland (or UP) and the majority of the 19th century Free Church of Scotland. The majority of the United Free Church of Scotland united with the Church of Scotland in 1929.

Contents

1 Origins

2 Legal dispute:The Free Church Case

3 Existence 1900–1929

4 Union with the Church of Scotland

5 The continuing UFC, 1929–present

5.1 Ecumenical relations

6 Moderators of the General Assembly of the United Free Church

7 See also

8 References

9 External links

Origins

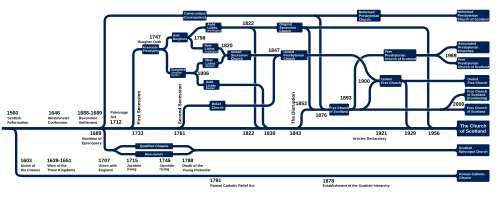

Timeline showing the evolution of the churches of Scotland from 1560

The Free Church of Scotland seceded from the Church of Scotland in the Disruption of 1843. The United Presbyterian Church was formed in 1847 by a union of the United Secession and Relief Churches, both of which had split from the Church of Scotland. The two denominations united in 1900 to form the United Free Church (except for a small section of the Free Church who rejected the union and continued independently under the name of the Free Church).

Legal dispute:The Free Church Case

The minority of the Free Church, which had refused to join the union, quickly tested its legality. They issued a summons, claiming that in altering the principles of the Free Church, the majority had ceased to be the Free Church of Scotland and therefore forfeited the right to its assets – which should belong to the remaining minority, who were the true 'Free Church'. However, the case was lost in the Court of Session, where Lord Low (upheld by the second division) held that the Assembly of original Free Church had a right, within limits, to change its position.

An appeal to House of Lords, (not delivered until 1 August 1904 due to a judicial death), reversed the Court of Session's decision (by a majority of 5–2), and found the minority entitled to the assets of the Free Church. It was held that, by adopting new standards of doctrine (and particularly by abandoning its commitment to 'the establishment principle' – which was held to be fundamental to the Free Church), the majority had violated the conditions on which the property of the Free Church was held.

The judgement had huge implications; seemingly it deprived the Free Church element of the UF Church of all assets—churches, manses, colleges, missions, and even provision for elderly clergy. It handed large amounts of property to the remnant; more than it could make effective use of. A conference, held in September 1904, between representatives of the UF and the (now distinct) Free Church, to come to some working arrangement, found that no basis for agreement could be found. A convocation of the UF Church, held on 15 December, decided that the union should proceed, and resolved to pursue every lawful means to restore their assets. As a result, the intervention of Parliament was sought.

A parliamentary commission was appointed, consisting of Lords Elgin, Kinnear and Anstruther. The question of interim possession was referred to Sir John Cheyne. The commission sat in public, and after hearing both sides, issued their report in April 1905. They stated that the feelings of both parties towards the other had made their work difficult. They concluded, however, that the Free Church was in many respects unable to carry out the purposes of the trusts, which, under the ruling of the House of Lords, was a condition of their holding the property. They recommended that an executive commission should be set up by act of parliament, in which the whole property of the Free Church, as at the date of the union, should be vested, and which should allocate it to the United Free Church, where the Free Church was unable to carry out the trust purposes.

The Churches (Scotland) Act 1905, which gave effect to these recommendations, was passed in August. The commissioners appointed were those on whose report the act was formed, plus two others. The allocation of churches and manses was a slow business, but by 1908 over 100 churches had been assigned to the Free Church. Some of the dispossessed UF Church congregations, most of them in the Highlands, found shelter for a time in the parish churches; but it was early decided that in spite of the objection against the erection of more church buildings in districts where many were now standing empty, 60 new churches and manses should at once be built at a cost of about £150,000. In October 1906 the commission intimated that the Assembly Hall, and the New College Buildings, were to belong to the U.F Church, while the Free Church received the offices in Edinburgh, and a tenement to be converted into a college, while the library was to be vested in the UF Church, but open to members of both. After having held its Assembly in university class-rooms for two years, and in another hall in 1905, in 1906 the UF Church again occupied the historic buildings of the Free Church. All the foreign missions and all the continental stations were also adjudged to the United Free Church. (Incidentally, the same act also contained provided for the relaxation of subscription in the Church of Scotland, thus Parliament had involved itself in the affairs of all Presbyterian churches.)

Existence 1900–1929

| Religion in Scotland |

|---|

|

|

The United Free Church was during its relatively short existence the second largest Presbyterian church in Scotland. The Free Church brought into the union 1,068 congregations, the United Presbyterians 593. Combined they had a membership of some half a million Scots. The revenue of the former amounted to £706,546, of the latter to £361,743. The missionaries of both churches joined the union, and the united Church was then equipped with missions in various parts of India, in Manchuria, in Africa (Lovedale, Livingstonia, etc.), in Palestine, in Melanesia and in the West Indies.

The UFC was broadly liberal Evangelical in its approach to theology and practical issues. It combined an acceptance of the findings of contemporary science, and the more moderate results of higher criticism with commitment to evangelism and missions. The UFC an approach to doctrinal conformity, which was fairly liberal for a Presbyterian denomination at the time. In its 1906 Act Anent Spiritual Independence of the Church, its General Assembly asserted the power to modify or define its Subordinate standard (the Westminster Confession) and its laws. Although its subordinate standard remained, ministers and elders were asked to state their belief in "the doctrine of this Church, set forth in the Confession of Faith". Thus the Church's interpretation of doctrine was prioritised over the confession.[citation needed]

The UFC had three divinity halls, at Glasgow, Edinburgh and Aberdeen, served by 17 professors and five lecturers. The first moderator was Robert Rainy. Its theologians and scholars have included H.R. Mackintosh, James Moffatt as well as John and Donald Baillie. British Prime Minister Bonar Law was raised in a Canadian Free Church manse and was a member of the United Free Church in Helensburgh.[3]

Union with the Church of Scotland

As its early days were preoccupied with the aftermath of union, so its later days were with the coming union with the Church of Scotland. The problem was the CofS's position as an established church conflicted with the Voluntaryism of the UFC. Discussions began in 1909, but were complex. The Very Rev William Paterson Paterson, Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland made much progress during his period in office 1919/20.[4]

The main hurdles were overcome by two parliamentary statutes, firstly the Church of Scotland Act 1921, which recognised the Church of Scotland's independence in spiritual matters (a right asserted by its Articles Declaratory of 1919). The second was the Church of Scotland (Properties and Endowments) Act 1925, which transferred the secular endowment of the church to a new body called the General Trustees. These measures satisfied the majority of the UFC that the Church-state entanglement of the Church of Scotland, which had been the cause of the Disruption of 1843 had at last ended. In 1929, the merger with the Church of Scotland largely reversed the Disruption of 1843 and reunited much of Scottish Presbyterianism. On 2 October 1929, at an assembly at the Industrial Hall on Annandale Street off Leith Walk in Edinburgh, the two churches merged.[5] The Hall is now the central bus depot for Lothian Region Transport.

A relatively small minority stayed out of the union, and retained the name of U.F. Church.

The continuing UFC, 1929–present

Voluntaryism led some to oppose the union (the United Free Church Association, led by James Barr – minister of Govan and Labour MP for Motherwell). When it came, 14,000 UFC members remained outside, calling themselves the United Free Church (Continuing). The phrase 'continuing' was used for five years to avoid confusion between the remaining United Free Church and the pre-union Church. It was dropped from the title in 1934. An agreement between the parties avoided the property disputes of the 1900 union.

The ongoing UFC continues in the 'broad evangelical' tradition.

The continuing UFC first ordained a female minister in 1929.[6] The church elected a woman as its moderator in 1960,[6] when Elizabeth Barr became the first female moderator of a general assembly of a Scottish church.[7]

In 2016, the UFC had 53 congregations in its three presbyteries.[8] These three presbyteries are 'The East', 'The West' and 'The North'.

- The East: meets in Bo'ness and covers central Scotland, South Fife and the Lothians. It has 13 congregations.

- The West which meets in Glasgow and covers Strathclyde, and has 26 congregations within its bounds.

- The North meets in Aberdeen and Perth covering Tayside, The Highlands, Grampian and the Northern Isles. It has 14 congregations.

The General Assembly of the United Free Church of Scotland meets annually, beginning on the Wednesday after the first Sunday in June, and lasting until the Friday. Since 2008, they have committed to having the General Assembly in a central location, meeting in the Salutation Hotel, Perth.[8]

In 2016, they had 60 ordained ministers, including retired and those serving part-time. There were three students, and a further three probationer ministers. The denomination has 388 Elders, and 255 Deacons, Managers or board members who are not Elders.

Ecumenical relations

The modern UFC is involved in the ecumenical movement in Scotland and is a member of Action of Churches Together in Scotland.[9] It is also a member of the Community of Protestant Churches in Europe and the World Communion of Reformed Churches.

Moderators of the General Assembly of the United Free Church

Dugald Mackichan (1917)

Adam Philip (1921)

See also

- History of Scotland

- United and uniting churches

References

^ https://www.ufcos.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/General%20Assembly/2017/AF-GA17.pdf

^ https://www.ufcos.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/General%20Assembly/2017/AF-GA17.pdf

^ Noble, Stewart. "History of Helensburgh Parish Church". Helensburgh Heritage. Retrieved 28 April 2017..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ https://www.giffordlectures.org/lecturers/william-paterson-paterson

^ Edinburgh and District: Ward Lock Travel Guide 1939

^ ab Jacqueline Field-Bibb, Women Towards Priesthood: Ministerial Politics and Feminist Praxis (Cambridge University Press, 1991), p. 117.

^ Keith Robbins, England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales: The Christian Church 1900–2000 (Oxford University Press, 2008), pp. 387–88.

^ ab Report of the Administration and Finance Committee General Assembly 2017 (PDF). 2017. p. 9. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

^ "Who we are: Member Churches". acts-scotland.org/. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- Cameron, N. et al. (eds.) Dictionary of Scottish Church History and Theology, Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1993.

External links

Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article United Free Church of Scotland. |

- Official website