Gustave Eiffel

Gustave Eiffel | |

|---|---|

Eiffel in 1888, photographed by Félix Nadar | |

| Born | Alexandre Gustave Bonickhausen dit Eiffel[1][2][3] (1832-12-15)15 December 1832 Dijon, Côte-d'Or, Burgundy, France |

| Died | 27 December 1923(1923-12-27) (aged 91) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater | École Centrale Paris |

| Spouse(s) | Marguerite Gaudelet (married 1862–1877) |

| Children | 3 daughters, 2 sons |

| Parent(s) | Alexandre and Catherine Eiffel |

| Signature | |

| |

Alexandre Gustave Eiffel (born Bonickhausen dit Eiffel;[1]/ˈaɪfəl/; French pronunciation: [ɛfɛl]; 15 December 1832 – 27 December 1923) was a French civil engineer. A graduate of École Centrale Paris, he made his name building various bridges for the French railway network, most famously the Garabit viaduct. He is best known for the world-famous Eiffel Tower, built for the 1889 Universal Exposition in Paris, and his contribution to building the Statue of Liberty in New York. After his retirement from engineering, Eiffel focused on research into meteorology and aerodynamics, making significant contributions in both fields.

Contents

1 Early life

1.1 Early career

1.2 Eiffel et Cie

1.2.1 The Eiffel Tower

1.2.2 The Panama Scandal

1.3 Later career

2 Influence

3 Works

3.1 Buildings and structures

3.2 Bridges and viaducts

3.3 Not proven

3.4 Unrealized projects

4 Protection of Gustave Eiffel's heritage

5 See also

6 Bibliography

7 References

8 External links

Early life

Gustave Eiffel was born in Burgundy, France, in the city of Dijon, Côte-d'Or, the first child of Catherine-Mélanie (née Moneuse) and Alexandre Bönickhausen (French pronunciation: [bɔnikozɑ̃]).[4] He was a descendant of Jean-René Bönickhausen, who had emigrated from the German town of Marmagen and settled in Paris at the beginning of the 18th century.[5] The family adopted the name Eiffel as a reference to the Eifel mountains in the region from which they had come. Although the family always used the name Eiffel, Gustave's name was registered at birth as Bonickhausen dit Eiffel,[1] and was not officially changed to Eiffel until 1880.[2][6]

At the time of Gustave's birth his father, an ex-soldier, was working as an administrator for the French Army; but shortly after his birth, his mother expanded a charcoal business, and soon afterwards his father gave up his job to assist her. Due to his mother's business commitments, Gustave spent his childhood living with his grandmother, but nevertheless remained close to his mother, who was to remain an influential figure until her death in 1878. His father, however, did not play a big part in young Eiffel's early life. The business was successful enough for Catherine Eiffel to sell it in 1843 and retire on the proceeds.[7] Eiffel was not a studious child, and thought his classes at the Lycée Royal in Dijon boring and a waste of time, although in his last two years, influenced by his teachers for history and literature, he began to study seriously, and he gained his baccalauréats in humanities and science.[8]

An important part in his education was played by his uncle, Jean-Baptiste Mollerat, who had invented a process for distilling vinegar and had a large chemical works near Dijon, and one of his uncle's friends, the chemist Michel Perret. Both men spent a lot of time with the young Eiffel, teaching him about everything from chemistry and mining to theology and philosophy.

Eiffel went on to attend the Collège Sainte-Barbe in Paris, to prepare for the difficult entrance exams set by engineering colleges in France, and qualified for entry to two of the most prestigious schools – École polytechnique and École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures – and ultimately entered the latter.[9] During his second year he chose to specialize in chemistry, and graduated ranking at 13th place out of 80 candidates in 1855. This is what is thought to be one of the things that led young Eiffel into his career of engineering. This was the year that Paris hosted the second World's Fair, and Eiffel was bought a season ticket by his mother.[10]

Early career

The Bordeaux bridge, Eiffel's first major work.

After graduation, Eiffel had hoped to find work in his uncle's workshop in Dijon, but a family dispute made this impossible. After a few months working as an unpaid assistant to his brother-in-law, who managed a foundry, Eiffel approached the railway engineer Charles Nepveu, who gave Eiffel his first paid job as his private secretary.[11] However, shortly afterwards Nepveu's company went bankrupt, but Nepveu found Eiffel a job designing a 22 m (72 ft) sheet iron bridge for the Saint Germaine railway. Some of Nepveu's businesses were then acquired by the Compagnie Belge de Matériels de Chemin de Fer: Nepveu was appointed the managing director of the two factories in Paris, and offered Eiffel a job as head of the research department. In 1857 Nepveu negotiated a contract to build a railway bridge over the river Garonne at Bordeaux, connecting the Paris-Bordeaux line to the lines running to Sète and Bayonne, which involved the construction of a 500 m (1,600 ft) iron girder bridge supported by six pairs of masonry piers on the river bed. These were constructed with the aid of compressed air caissons and hydraulic rams, both innovative techniques at the time. Eiffel was initially given the responsibility of assembling the metalwork and eventually took over the management of the entire project from Nepveu, who resigned in March 1860.[12]

Following the completion of the project on schedule Eiffel was appointed as the principal engineer of the Compagnie Belge. His work had also gained the attention of several people who were later to give him work, including Stanislas de la Roche Toulay, who had prepared the design for the metalwork of the Bordeaux bridge, Jean Baptiste Krantz and Wilhelm Nordling. Further promotion within the company followed, but the business began to decline, and in 1865 Eiffel, seeing no future there, resigned and set up as an independent consulting engineer. He was already working independently on the construction of two railway stations, at Toulouse and Agen, and in 1866 he was given a contract to oversee the construction of 33 locomotives for the Egyptian government, a profitable but undemanding job in the course of which he visited Egypt, where he visited the Suez Canal which was being constructed by Ferdinand de Lesseps. At the same time he was employed by Jean-Baptiste Kranz to assist him in the design of the exhibition hall for the Exposition Universelle which was to be held in 1867. Eiffel's principal job was to draw up the arch girders of the Galerie des Machines. In order to carry out this work, Eiffel and Henri Treca, the director of the Conservatoire des Arts et Metiers,[13] conducted valuable research on the structural properties of cast iron, definitively establishing the modulus of elasticity applicable to compound castings.

Eiffel et Cie

The Budapest-Nyugati station.

At the end of 1866 Eiffel managed to borrow enough money to set up his own workshops at 48 Rue Fouquet in Levallois-Perret.[14] His first important commission was for two viaducts for the railway line between Lyon and Bordeaux, and the company also began to undertake work in other countries, including the church of San Marcos in Arica, Chile, which was an all-metal prefabricated building, manufactured in France and shipped to South America in pieces to be assembled on site.

On 6 October 1868 he entered into partnership with Théophile Seyrig, like Eiffel a graduate of the École Centrale, forming the company Eiffel et Cie ("Eiffel and Company").

In 1875, Eiffel et Cie were given two important contracts, one for a new terminus for the line from Vienna to Budapest and the other for a bridge over the river Douro in Portugal.[15] The station in Budapest was an innovative design. The usual pattern for building a railway terminus was to conceal the metal structure behind an elaborate facade: Eiffel's design for Budapest used the metal structure as the centerpiece of the building, flanked on either side by conventional stone and brick-clad structures housing administrative offices.

The Maria Pia Bridge

The bridge over the Douro came about as the result of a competition held by the Royal Portuguese Railroad Company. The task was a demanding one: the river was fast-flowing, up to 20 m (66 ft) deep, and had a bed formed of a deep layer of gravel which made the construction of piers on the river bed impossible, and so the bridge had to have a central span of 160 m (520 ft). This was greater than the longest arch span which had been built at the time.[16]

Eiffel's proposal was for a bridge whose deck was supported by five iron piers, with the abutments of the pair on the river bank also bearing a central supporting arch. The price quoted by Eiffel was FF.965,000, far below the nearest competitor and so he was given the job, although since his company was less experienced than his rivals the Portuguese authorities appointed a committee to report on Eiffel et Cie's suitability. The members included Jean-Baptiste Krantz, Henri Dion and Léon Molinos, both of whom had known Eiffel for a long time: their report was favorable, and Eiffel got the job. On-site work began in January 1876 and was complete by the end of October 1877: the bridge was ceremonially opened by King Luis I and Queen Maria Pia, after whom the bridge was named, on 4 November.

The Exposition Universelle in 1878 firmly established his reputation as one of the leading engineers of the time. As well as exhibiting models and drawings of work undertaken by the company, Eiffel was also responsible for the construction of several of the exhibition buildings.[17] One of these, a pavilion for the Paris Gas Company, was Eiffel's first collaboration with Stephen Sauvestre, who was later to become the head of the company's architectural office.

In 1879 the partnership with Seyrig was dissolved, and the company was renamed the Compagnie des Établissements Eiffel.[18]

The same year the company was given the contract for the Garabit viaduct, a railway bridge near Ruynes en Margeride in the Cantal département. Like the Douro bridge, the project involved a lengthy viaduct crossing the river valley as well as the river itself, and Eiffel was given the job without any process of competitive tendering due to his success with the bridge over the Douro.[19] To assist him in the work he took on several people who were to play important roles in the design and construction of the Eiffel Tower, including Maurice Koechlin, a young graduate of the Zurich Polytechnikum, who was engaged to undertake calculations and make drawings, and Émile Nouguier, who had previously worked for Eiffel on the construction of the Douro bridge.

Interior structural elements of the Statue of Liberty designed by Gustave Eiffel.

The same year Eiffel started work on a system of standardised prefabricated bridges, an idea that was the result of a conversation with the governor of Cochin-China. These used a small number of standard components, all small enough to be readily transportable in areas with poor or non-existent roads, and were joined together using bolts rather than rivets, reducing the need for skilled labour on site. A number of different types were produced, ranging from footbridges to standard-gauge railway bridges.[20]

In 1881 Eiffel was contacted by Auguste Bartholdi who was in need of an engineer to help him to realise the Statue of Liberty. Some work had already been carried out by Eugène Viollet-Le-Duc, but he had died in 1879. Eiffel was selected because of his experience with wind stresses. Eiffel devised a structure consisting of a four-legged pylon to support the copper sheeting which made up the body of the statue. The entire statue was erected at the Eiffel works in Paris before being dismantled and shipped to the United States.[21]

In 1886 Eiffel also designed the dome for the Astronomical Observatory in Nice. This was the most important building in a complex designed by Charles Garnier, later among the most prominent critics of the Tower. The dome, with a diameter of 22.4 m (73 ft), was the largest in the world when built and used an ingenious bearing device: rather than running on wheels or rollers, it was supported by a ring-shaped hollow girder floating in a circular trough containing a solution of magnesium chloride in water. This had been patented by Eiffel in 1881.

The Eiffel Tower

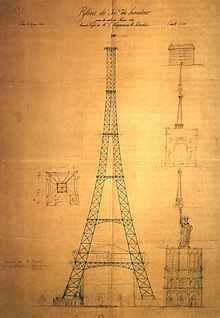

Koechlin's first drawing for the Eiffel Tower. Note the sketched stack of buildings, with Notre Dame at the bottom, indicating the scale of the proposed tower.

The design of the Eiffel Tower was originated by Maurice Koechlin and Emile Nouguier, who had discussed ideas for a centrepiece for the 1889 Exposition Universelle. In May 1884 Koechlin, working at his home, made an outline drawing of their scheme, described by him as "a great pylon, consisting of four lattice girders standing apart at the base and coming together at the top, joined together by metal trusses at regular intervals".[22] Initially Eiffel showed little enthusiasm, although he did sanction further study of the project, and the two engineers then asked Stephen Sauvestre to add architectural embellishments. Sauvestre added the decorative arches to the base, a glass pavilion to the first level and the cupola at the top. The enhanced idea gained Eiffel's support for the project, and he bought the rights to the patent on the design which Koechlin, Nougier, and Sauvestre had taken out. The design was exhibited at the Exhibition of Decorative Arts in the autumn of 1884, and on 30 March 1885 Eiffel read a paper on the project to the Société des Ingénieurs Civils. After discussing the technical problems and emphasising the practical uses of the tower, he finished his talk by saying that the tower would symbolise[23]

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

not only the art of the modern engineer, but also the century of Industry and Science in which we are living, and for which the way was prepared by the great scientific movement of the eighteenth century and by the Revolution of 1789, to which this monument will be built as an expression of France's gratitude.

Little happened until the beginning of 1886, but with the re-election of Jules Grévy as President and his appointment of Edouard Lockroy as Minister for Trade decisions began to be made. A budget for the Exposition was passed and on 1 May Lockroy announced an alteration to the terms of the open competition which was being held for a centerpiece for the exposition, which effectively made the choice of Eiffel's design a foregone conclusion: all entries had to include a study for a 300 m (980 ft) four-sided metal tower on the Champ de Mars. On 12 May a commission was set up to examine Eiffel's scheme and its rivals and on 12 June it presented its decision, which was that only Eiffel's proposal met their requirements. After some debate about the exact site for the tower, a contract was signed on 8 January 1887. This was signed by Eiffel acting in his own capacity rather than as the representative of his company, and granted him one and a half million francs toward the construction costs. This was less than a quarter of the estimated cost of six and a half million francs. Eiffel was to receive all income from the commercial exploitation during the exhibition and for the following twenty years.[24] Eiffel later established a separate company to manage the tower.

The tower had been a subject of some controversy, attracting criticism both from those who did not believe it feasible and from those who objected on artistic grounds. Just as work began at the Champ de Mars, the "Committee of Three Hundred" (one member for each metre of the tower's height) was formed, led by Charles Garnier and including some of the most important figures of the French arts establishment, including Adolphe Bouguereau, Guy de Maupassant, Charles Gounod and Jules Massenet: a petition was sent to Jean-Charles Alphand, the Minister of Works, and was published by Le Temps.[25]

To bring our arguments home, imagine for a moment a giddy, ridiculous tower dominating Paris like a gigantic black smokestack, crushing under its barbaric bulk Notre Dame, the Tour de Saint-Jacques, the Louvre, the Dome of les Invalides, the Arc de Triomphe, all of our humiliated monuments will disappear in this ghastly dream. And for twenty years ... we shall see stretching like a blot of ink the hateful shadow of the hateful column of bolted sheet metal.

Eiffel responded to such criticism by comparing his tower to the Egyptian pyramids:

Do you think it is for their artistic value that the pyramids have so powerfully struck the imagination of men? What are they, after all, but artificial mountains? [The aesthetic impact of the pyramids was found in] the immensity of the effort and the grandeur of the result. My tower will be the highest structure that has ever been built by men. Why should that which is admirable in Egypt become hideous and ridiculous in Paris?[26]

18 July 1887

7 December 1887

20 March 1888

15 May 1888

21 August 1888

26 December 1888

March 1889

Caricature of Eiffel, published in 1887 at the time of "The Artist's Protest"

Work on the foundations started on 28 January 1887. Those for the east and south legs were straightforward, each leg resting on four 2 m (6.6 ft) concrete slabs, one for each of the principal girders of each leg but the other two, being closer to the river Seine were more complicated: each slab needed two piles installed by using compressed-air caissons 15 m (49 ft) long and 6 m (20 ft) in diameter driven to a depth of 22 m (72 ft)[27] to support the concrete slabs, which were 6 m (20 ft) thick. Each of these slabs supported a limestone block, each with an inclined top to bear the supporting shoe for the ironwork. These shoes were anchored by bolts 10 cm (4 in) in diameter and 7.5 m (25 ft) long.

Work on the foundations was complete by 30 June and the erection of the iron work was started. Although no more than 250 men were employed on the site, a prodigious amount of exacting preparatory work was entailed: the drawing office produced 1,700 general drawings and 3,629 detail drawings of the 18,038 different parts needed.[28] The task of drawing the components was complicated by the complex angles involved in the design and the degree of precision required: the positions of rivet holes were specified to within 0.1 mm (0.04 in) and angles worked out to one second of arc. The components, some already riveted together into sub-assemblies, were first bolted together, the bolts being replaced by rivets as construction progressed. No drilling or shaping was done on site: if any part did not fit it was sent back to the factory for alteration. The four legs, each at an angle of 54° to the ground, were initially constructed as cantilevers, relying on the anchoring bolts in the masonry foundation blocks. Eiffel had calculated that this would be satisfactory until they approached halfway to the first level: accordingly work was stopped for the purpose of erecting a wooden supporting scaffold. This gave ammunition to his critics, and lurid headlines including "Eiffel Suicide!" and "Gustave Eiffel has gone mad: he has been confined in an Asylum" appeared in the popular press.[29] At this stage a small "creeper" crane was installed in each leg, designed to move up the tower as construction progressed and making use of the guides for the elevators which were to be fitted in each leg. After this brief pause erection of the metalwork continued, and the critical operation of linking the four legs was successfully completed by March 1888. In order to precisely align the legs so that the connecting girders could be put into place, a provision had been made to enable precise adjustments by placing hydraulic jacks in the footings for each of the girders making up the legs.

The main structural work was completed at the end of March, and on the 31st Eiffel celebrated this by leading a group of government officials, accompanied by representatives of the press, to the top of the tower. Since the lifts were not yet in operation, the ascent was made by foot, and took over an hour, Eiffel frequently stopping to make explanations of various features. Most of the party chose to stop at the lower levels, but a few, including Nouguier, Compagnon, the President of the City Council and reporters from Le Figaro and Le Monde Illustré completed the climb. At 2.35 Eiffel hoisted a large tricolour, to the accompaniment of a 25-gun salute fired from the lower level.[30]

By June construction had reached the second level platform, and on Bastille Day this was used for a fireworks display, and Eiffel held a celebratory banquet for the press on the first level platform.

The Panama Scandal

Illustration of Eiffel's lock design from a contemporary magazine

In 1887, Eiffel became involved with the French effort to construct a canal across the Panama Isthmus. The French Panama Canal Company, headed by Ferdinand de Lesseps, had been attempting to build a sea-level canal, but came to the realization that this was impractical. The plan was changed to one using locks, which Eiffel was contracted to design and build. The locks were on a large scale, most having a change of level of 11 m (36 ft).[31] Eiffel had been working on the project for little more than a year when the company suspended payments of interest on 14 December 1888,[32] and shortly afterwards was put into liquidation. Eiffel's reputation was badly damaged when he was implicated in the financial and political scandal which followed. Although he was simply a contractor, he was charged along with the directors of the project with raising money under false pretenses and misappropriation of funds. On 9 February 1893 Eiffel was found guilty on the charge of misuse of funds, and was fined 20,000 francs and sentenced to two years in prison,[33] although he was acquitted on appeal.[34] The later American-built canal used new lock designs (see History of the Panama Canal).

Shortly after the trial Eiffel had announced his intention to resign from the Board of Directors of the Compagnie des Etablissements Eiffel, and did so at a General Meeting held on 14 February, saying "I have absolutely decided to abstain from any participation in any manufacturing business from now on, and so that no one can be misled and to make it most evident that I intend to remain absolutely uninvolved with the management of the establishments which bear my name, I insist that my name should disappear from the name of the company."[35] The company changed its name to La Société Constructions Levallois-Perret, with Maurice Koechlin as managing director. The name was changed to the Anciens Etablissements Eiffel in 1937.[36]

Later career

Eiffel in 1910

About six months after his retirement from the Compagnie des Etablissements Eiffel, Eiffel was approached by Felix-Max Richard, owner of the Comptoir General de Photographie. Felix-Max Richard had just lost a lawsuit against him by his brother to enforce a noncompetition agreement. Felix-Max Richard appealed the decision but felt he needed a back-up plan if his appeal was denied. On May 28, 1895, the court denied the appeal and Gustave Eiffel bought the Comptoir with three other men: Joseph Vallot, Alfred Besnier, and Leon Gaumont, who was thirty years his junior.[37] The company was renamed L. Gaumont et Cie after its youngest partner because Eiffel did not want his name on the company. Leon Gaumont was manager and Eiffel was president from 1895 through 1906. The company went public in January 1907 and is one of the oldest motion picture companies in the world.

During those years, Eiffel guided the company, contributed to its capital investments and inventions, and was absorbed by the new technologies and decisions the company made in its first eleven years. In 1897, he collaborated with Louis-Paul Cailletet and Leon Gaumont on a motion picture camera that was installed in a hot-air balloon. According to the correspondence between Gaumont and Eiffel, Eiffel had dark rooms at his Beauleau-Sur-Mer and Vevey vacation homes where he experimented with chemical developers. He patented a photographic heliograph in 1907.[38][39]

He went on to do important work in meteorology and aerodynamics.[40] Eiffel's interest in these areas was a consequence of the problems he had encountered with the effects of wind forces on the structures he had built.

His first aerodynamic experiments, an investigation of the air resistance of surfaces, was carried out by dropping the surface to be investigated together with a measuring apparatus down a vertical cable stretched between the second level of the Eiffel Tower and the ground. Using this Eiffel definitely established that the air resistance of a body was very closely related to the square of the airspeed. He then built a laboratory on the Champ de Mars at the foot of the tower in 1905, building his first wind tunnel there in 1909. The wind tunnel was used to investigate the characteristics of the airfoil sections used by the early pioneers of aviation such as the Wright Brothers, Gabriel Voisin and Louis Blériot. Eiffel established that the lift produced by an airfoil was the result of a reduction of air pressure above the wing rather than an increase of pressure acting on the under surface. Following complaints about noise from people living nearby, he moved his experiments to a new establishment at Auteuil in 1912. Here it was possible to build a larger wind tunnel, and Eiffel began to make tests using scale models of aircraft designs.[41]

In 1913 Eiffel was awarded the Samuel P. Langley Medal for Aerodromics by the Smithsonian Institution. In his speech at the presentation of the medal, Alexander Graham Bell said:[42]

... his writings upon the resistance of the air have already become classical. His researches, published in 1907 and 1911, on the resistance of the air in connection with aviation, are especially valuable. They have given engineers the data for designing and constructing flying machines upon sound, scientific principles

Eiffel had meteorological measuring equipment placed on the tower in 1889, and also built a weather station at his house in Sèvres. Between 1891 and 1892 he compiled a complete set of meteorological readings, and later extended his record-taking to include measurements from 25 different locations across France.

Eiffel died on 27 December 1923, while listening to Beethoven's 5th Symphony, Second movement Andante, in his mansion on Rue Rabelais in Paris, France. He was buried in the family tomb in Levallois-Perret Cemetery.

Influence

Edward Moran's 1886 painting, The Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World, depicts the unveiling of the Statue of Liberty.

Gustave Eiffel's career was facilitated by the Industrial Revolution. For a variety of economic and political reasons, this had been slow to make an impact in France,[43] and Eiffel had the good fortune to be working at a time of rapid industrial development in France. Eiffel's importance as an engineer was twofold. Firstly he was ready to adopt innovative techniques first used by others, such as his use of compressed-air caissons and hollow cast-iron piers, and secondly he was a pioneer in his insistence on basing all engineering decisions on thorough calculation of the forces involved, combining this analytical approach with an insistence on a high standard of accuracy in drawing and manufacture.

The growth of the railway network had an immense effect on people's lives, but although the enormous number of bridges and other work undertaken by Eiffel were an important part of this, the two works that did most to make him famous are the Statue of Liberty and the Eiffel Tower, both projects of immense symbolic importance and today internationally recognized landmarks. The Tower is also important because of its role in establishing the aesthetic potential of structures whose appearance is largely dictated by practical considerations.

His contribution to the science of aerodynamics is probably of equal importance to his work as an engineer.[40]

Works

Buildings and structures

Cathedral of San Pedro de Tacna, Peru.

The "Grand Hotel Traian" from Iaşi, is Gustave Eiffel's link to Romania

Konak Pier in İzmir, Turkey, designed by Gustave Eiffel

- Railway station at Toulouse, France (1862)

- Railway station at Agen, France.

- Church of Notre Dame des Champs, Paris (1867)

- Performing Artes Center Lía Bermúdez, Maracaibo, Venezuela (1886)

- Synagogue in Rue de Pasarelles, Paris (1867)

Théâtre les Folies, Paris (1868)- Gasworks, La Paz, Bolivia (1873)

- Gasworks, Tacna, Peru (1873)

Church of San Marcos, Arica, Chile (1875)

Cathedral of San Pedro de Tacna, Peru (1875)

Lycée Carnot, Paris (1876)

Budapest-Nyugati Pályaudvar (Western railway station), Budapest, Hungary (1877)- Ornamental Fountain of the Three Graces, Moquegua, Peru (1877)

- Ruhnu Lighthouse at Ruhnu island, Estonia (1877)

- Grand Hotel Traian, Iași, Romania (1882)

Nice Observatory, Nice, France (1886)

Statue of Liberty, Liberty Island, New York City, United States (1886)

Colbert Bridge, Dieppe, France (1888)

Eiffel Tower, Paris, France (1889)

Paradis Latin theatre, Paris, France (1889)

Casa de Fierro, Iquitos, Peru (1892)

Estación Central (railway station), Santiago, Chile, (1897)

Iglesia de Santa Bárbara in Santa Rosalía, Baja California Sur, Mexico (1897)- lighthouse on Dzharylhach island, Kherson region, Ukraine (1902)

- Aérodynamique EIFFEL (wind tunnel), Paris (Auteuil), France (1911)

- The Market, Olhão, Portugal

- Palacio de Hierro, Orizaba, Veracruz, Mexico

- Catedral de Santa María, Chiclayo, Peru (late 20th century)

- Condominio Acero, Monterrey, Nuevo León, México

- Combier Distillery, Saumur (Loire Valley), France

La Paz Bus Station

La Paz Train Station, La Paz, Bolivia (now La Paz Bus Station)- Church in Coquimbo, Chile

- Fénix Theatre, Arequipa, Peru

- San Camilo Market, Arequipa, Peru

- Farol de São Thomé, Campos, Brazil

- Pabellon de la Rosa Piriápolis, Uruguay

- Mercado Municipal, Manaus, Brazil

- La Cristalera, old portuary storage, El Puerto de Santa María, Spain

- Clock Tower, Monte Cristi, Dominican Republic

Bridges and viaducts

Eiffel bridge in Caminha

Eiffel Bridge in Ungheni

Eiffel Bridge in Sarajevo 1893, also known as Skenderija Bridge, spans the Miljacka.

- Railway bridge over the river Garonne, Bordeaux (1861)

- Viaduct over the river Sioule (1867)

- Viaduct at Neuvial (1867)

- Swing bridge at Dieppe (1870)

Pont de Ferro or Pont Eiffel in Girona, Spain. (1876)

Maria Pia Bridge (Douro Viaduct) (1877)

Cubzac bridge over the Dordogne River, France (1880)

Borjomi bridge over the Tsemistskali River, Georgia (1902)- Road bridge over the river Tisza near Szeged, Hungary (1881)

Garabit Viaduct, France (1884)- Imbaba Bridge over the Nile river, Cairo, Egypt (1892)

- The Eiffel Bridge in Zrenjanin (1904) (dismantled in the 1960s and currently being rebuilt.)

- The road (D50) bridge over the River Lay at Lavaud in the Vendée, France

Birsbrücke, Münchenstein, Switzerland which collapsed on 14 June 1891 killing over 70 people. See Munchenstein rail disaster.- Bridge over the Schelde in Temse, Belgium

Souleuvre Viaduct (1893) (bridge spans removed but piers survive)- The Eiffel Bridge in Viana do Castelo's Marina (1878)

- The Railway Bridge over the Coura river in Caminha, Portugal.

Eiffel Bridge in Ungheni, between Moldova and Romania (1877)

Great bridge over the Begej in Zrenjanin, Serbia, built in 1904, dismantled and replaced by concrete bridge in 1969

Ajfel Bridge on Skenderija Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Ghenh Bridge and Rach Cat Bridge in Bien Hoa city, Đồng Nai Province, Vietnam.

- Trường Tiền Bridge in Huế city, Thừa Thiên–Huế Province, Vietnam.

- Bolívar Bridge, at Arequipa, Peru

Puente Ferroviario Banco de Arena Railway Bridge near Constitución, Chile

- Puente Libertador, San Cristóbal, Venezuela.

- The Railway Bridge in Przemyśl, Poland

Not proven

Basilica of San Sebastian, Manila, Philippines (1891)- Bridge over the Cuyuni River, southern Venezuela

- Santa Efigênia Viaduct, São Paulo, Brazil (1913)

Santa Justa Lift (Carmo Lift), in Lisbon, Portugal (1901)- Dam on Great Bačka Canal, Bečej, Vojvodina, Serbia (1900)

Malleco Viaduct, Chile (1890)- The Chateau de Villersexel, France (c. 1871)

- "Vuelta al Mundo", Córdoba, Argentina

- Watermill, Dolores, Córdoba, Argentina

- Casa del Cura (also called Casa Eiffel), in Ulea, Spain (1912)

Palácio de Ferro (Iron Palace), Angola

Mercado 2 de Abril, Mexico City

Unrealized projects

Trinity Bridge, Saint Petersburg – Eiffel entered a project into the contest, but his project was not realized.

Protection of Gustave Eiffel's heritage

A number of works of Gustave Eiffel are in danger today. Some have already been destroyed, as in Vietnam. A proposal to demolish the railway bridge of Bordeaux (also known as the "passerelle St Jean"), the first major work of Gustave Eiffel, resulted in a large response from the public. Actions to protect the bridge were taken as early as 2002 by the "Association of the Descendants of Gustave Eiffel",[44] joined from 2005 onwards by the Association "Sauvons la Passerelle Eiffel" ("Save the Eiffel Bridge"). They led, in 2010, to the decision to list Eiffel's Bordeaux bridge as a French Historical Monument.[45]

See also

Architecture portal

Architecture portal

Biography portal

Biography portal

France portal

France portal

Paris portal

Paris portal

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Harvie, David I. (2006). Eiffel, the Genius who Reinvented Himself. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton. ISBN 0-7509-3309-7..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Loyrette, Henri (1985). Gustave Eiffel. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 0-8478-0631-6.

References

^ abc État-civil de la Côte-d'Or, Dijon, Registres d'état civil 1832, p. 249

^ ab Harvie 2006 p. 1

^ Charles Braibant, Histoire de la Tour Eiffel, Paris 1964, p. 35

^ Harriss, J. (2004). The Tallest Tower. Unlimited Pub. p. 25. ISBN 9781588321046. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

^ Loyrette 1985, p. 21

^ "Follow the Leader". Google Books. 2016-09-15. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

^ Harvie 2006, p. 3

^ Loyrette 1985, p. 25

^ Harvie 2006, p. 7

^ Harvie 2006, p. 9

^ Loyrette 1985, p. 30

^ Loyrette 1985, p. 33

^ Harvie 2006, p. 37

^ Loyrette 1985, p. 37

^ Loyrette 1985, p. 57

^ Loyrette 1985, p. 60

^ Loyrette 1985, p. 71

^ Loyrette 1985, p. 42

^ Loyrette 1985, p. 77

^ Loyrette 1985, pp. 42–47

^ Harvie 2006, p. 70

^ Harvie 2006, p. 78

^ Loyrette 1985, p. 116

^ Loyrette 1985, p. 121

^ Harvie 2006, p. 95

^ Bayoumi, Moustafa (2000). "Shadows and Light: Colonial Modernity and the Grade Mosquée of Pairs". The Yale Journal of Criticism. volume 13, number 2: 267–292.

^ Loyrette 1985 p. 123

^ Loyrette 1985, p. 148

^ Harvie 206, p. 110

^ Harvie 2006 pp. 122–23

^ Loyrette 1985, p. 193

^ "The Panama Canal Company". The Times (32570): 7. 15 December 1888.

^ "Heavy Sentences On The Panama Defendants". The Times (33871): 5. 10 February 1893.

^ Gustave Eiffel. The official site of the Eiffel Tower. tour-eiffel.fr

^ "Historique des Etablissements Eiffel" (in French). Association des Descendants de Gustave Eiffel – gustaveeiffel. Archived from the original on 11 April 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2012.Je suis absolument décidé de m'abstenir désormais d'une participation quelconque dans une affaire industrielle, et afin que personne ne puisse s'y tromper et pour marquer de la façon la plus manifeste que j'entends rester désormais absolument étranger à la gestion des établissements qui portent mon nom, je tiens expressément à ce que mon nom disparaisse de la désignation de la société.

^ Harvie 2006, p. 40

^ Corcy, Malthete, Mannoni, & Meusy, Les Premieres annees de la societe L. Gaumont et Cie, Correspondance commercial de Leon Gaumont 1895-1899.

^ Couperie-Eiffel, Philippe, Eiffel by Eiffel, 2013

^ Dietrick, Janelle, Alice & Eiffel, A New History of Early Cinema and the Love Story Kept Secret for a Century, 2016

^ ab "The Death of a Great Pioneer: Gustav Eiffel Passes Away". Flight International. 3 January 1924

^ Granet, André. 1912 : Laboratoire Aerodynamique Eiffel. Laboratories Eiffel.

^ Harvie 2006, p. 207

^ Rolt, L.T.C. (1974). Victorian Engineering. London: Pelican. p. 169.

^ "Page d'accueil". Association des descendants de Gustave Eiffel. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

^ Retour à la liste des extraits des bulletins de l'ADGE. ADGE news bulletin (in French)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gustave Eiffel. |

- Official website of the Association of the Descendants of Gustave Eiffel (in English - biography, list of works, articles etc.)

- Gustave Eiffel: The Man Behind the Masterpiece

Gustave Alexandre Eiffel information at Structurae

- Einsturz der Birsbrücke bei Münchenstein (Basel)

Newspaper clippings about Gustave Eiffel in the 20th Century Press Archives of the German National Library of Economics (ZBW)