Sanctuary city

Sanctuary city (French: ville sanctuaire; Spanish: ciudad santuario) refers to municipal jurisdictions, typically in North America and Western Europe, that limit their cooperation with the national government's effort to enforce immigration law. Leaders of sanctuary cities say they want to reduce fear of deportation and possible family break-up among people who are in the country illegally, so that such people will be more willing to report crimes, use health and social services, and enroll their children in school. In the United States, municipal policies include prohibiting police or city employees from questioning people about their immigration status and refusing requests by national immigration authorities to detain people beyond their release date, if they were jailed for breaking local law.[1]

Such policies can be set expressly in law (de jure) or observed in practice (de facto), but the designation "sanctuary city" does not have a precise legal definition. The Federation for American Immigration Reform estimated in 2018 that more than 500 U.S. jurisdictions, including states and municipalities, had adopted sanctuary policies.[2]

Studies on the relationship between sanctuary status and crime have found that sanctuary policies either have no effect on crime or that sanctuary cities have lower crime rates and stronger economies than comparable non-sanctuary cities.[3][4][5][6] Opponents of sanctuary cities argue that cities should assist the national government in enforcing immigration law. Supporters of sanctuary cities argue that enforcement of national law is not the duty of localities.[7] Legal opinions vary on whether immigration enforcement by local police is constitutional.[8]

European cities have been inspired by the same political currents of the sanctuary movement as American cities, but the term "sanctuary city" now has different meanings in Europe and North America.[9] In the United Kingdom and Ireland, and in continental Europe, sanctuary city refers to cities that are committed to welcoming refugees, asylum seekers and others who are seeking safety. Such cities are now found in 80 towns, cities and local areas in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.[10] The emphasis is on building bridges of connection and understanding, which is done through raising awareness, befriending schemes and forming cultural connections in the arts, sport, health, education, faith groups and other sectors of society.[11]Glasgow and Swansea have become known as noted sanctuary cities.[10][12][13]

Contents

1 Tradition

2 United States

2.1 History

2.2 Terminology

2.3 Electoral politics

2.3.1 Trump administration agenda

2.4 Political action

2.5 State

2.5.1 Opposition

2.5.2 Support

2.5.3 Federal

2.6 Effects

2.6.1 Crime

2.6.2 Economy

2.6.3 Health and well-being

2.7 Laws and policies by state and city

2.7.1 Alabama

2.7.2 Arizona

2.7.3 California

2.7.4 Colorado

2.7.5 Connecticut

2.7.6 Florida

2.7.7 Georgia

2.7.8 Illinois

2.7.9 Louisiana

2.7.10 Maine

2.7.11 Maryland

2.7.12 Massachusetts

2.7.13 Michigan

2.7.14 Minnesota

2.7.15 New York

2.7.16 New Jersey

2.7.17 North Carolina

2.7.18 Ohio

2.7.19 Oregon

2.7.20 Pennsylvania

2.7.21 Washington

3 Canada

3.1 Ontario

3.2 Western Canada

4 United Kingdom

4.1 Sheffield

4.2 Glasgow

5 See also

6 References

7 Further reading

Tradition

The concept of a sanctuary city goes back thousands of years. It has been associated with Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Buddhism, Baha'i, Sikhism, and Hinduism.[14] In Western Civilization, sanctuary cities can be traced back to the Old Testament. The Book of Numbers commands the selection of six cities of refuge in which the perpetrators of accidental manslaughter could claim the right of asylum. Outside of these cities, blood vengeance against such perpetrators was allowed by law.[15] In AD 392, Christian Roman emperor Theodosius I set up sanctuaries under church control. In AD 600 in medieval England, churches were given a general right of sanctuary, and some cities were set up as sanctuaries by Royal charter. The general right of sanctuary for churches in England was abolished in 1621.[14]

United States

History

The movement that established sanctuary cities in the United States began in the early 1980s. The movement traces its roots to religious philosophy, as well as in histories of resistance movements to perceived state injustices.[16] The sanctuary city movement took place in the 1980s to challenge the US government’s refusal to grant asylum to certain Central American refugees. These asylum seekers were arriving from countries in Central America like El Salvador and Guatemala that were politically unstable. More than 75,000 Salvadoreans and 200,000 Guatemalans were killed by their governments in hopes to suppress the communist movement in those countries at the time.[17] Faith based groups in the US Southwest initially drove the movement of the 1980s, with eight churches publicly declaring sanctuary in March 1982.[18] John Fife, a minister and movement leader famously wrote in a letter to Attorney General William Smith, saying that the "South-side United Presbyterian Church will publicly violate the Immigration and Nationality Act" by allowing sanctuary in its church for those from Central America.[19]

A milestone in the U.S. sanctuary city movement occurred in 1985 in San Francisco, which passed the largely symbolic “City of Refuge” resolution. The resolution was followed the same year by an ordinance which prohibited the use of city funds and resources to assist federal immigration enforcement–the defining characteristic of a sanctuary city in the U.S.[20] As of 2018 more than 560 cities, states and counties considered themselves sanctuaries.[2]

Terminology

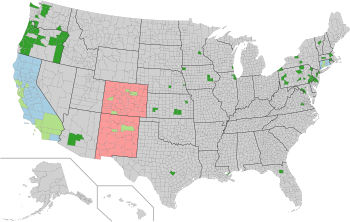

State has legislation in place that establishes a statewide sanctuary for illegal immigrants

County or county equivalent either contains a municipality that is a sanctuary for undocumented immigrants, or is one itself

All county jails in the state do not honor ICE detainers

Alongside statewide legislation or policies establishing sanctuary for illegal immigrants, county contains a municipality that has policy or has taken action to further provide sanctuary to undocumented immigrants

Several different terms and phrases are used to describe immigrants who enter the U.S. illegally. The term alien is "considered insensitive by many" and a LexisNexis search showed that its use in reports on immigration has declined substantially, making up just 5% of terms used in 2013.[21] Usage of the word "illegal" and phrases using the word (e.g., illegal alien, illegal immigrant, illegal worker and illegal migrant) has declined, accounting for 82% of language used in 1996, 75% in 2002, 60% in 2007, and 57% in 2013.[21] Several other phrases are competing for wide acceptance: undocumented immigrant (usage in news reports increased from 6% in 1996 to 14% in 2013); unauthorized immigrant (3% usage in 2013 and rarely seen before that time), and undocumented person or undocumented people (1% in 2007, increasing to 3% in 2013).[21] A recent term is "illegalized immigrant".[22]

Media outlets' policies as to use of terms differ, and no consensus has yet emerged in the press.[23][24] In 2013, the Associated Press changed its AP Stylebook to provide that "Except in direct quotes essential to the story, use illegal only to refer to an action, not a person: illegal immigration, but not illegal immigrant. Acceptable variations include living in or entering a country illegally or without legal permission."[25] Within several weeks, major U.S. newspapers such as Chicago Tribune, the Los Angeles Times, and USA Today adopted similar guidance.[24] The New York Times style guide similarly states that the term illegal immigrant may be considered "loaded or offensive" and advises journalists to "explain the specific circumstances of the person in question or to focus on actions: who crossed the border illegally; who overstayed a visa; who is not authorized to work in this country."[23] The style book discourages the use of illegal as a noun and the "sinister-sounding" alien.[23] Both unauthorized and undocumented are acceptable, but the stylebook notes that the former "has a flavor of euphemism and should be used with caution outside quotation" and the latter has a "bureaucratic tone."[23] The Washington Post stylebook "says 'illegal immigrant' is accurate and acceptable, but notes that some find it offensive"; the Post "does not refer to people as 'illegal aliens' or 'illegals,' per its guidelines.[26]

Electoral politics

This issue entered presidential politics in the race for the Republican Party Presidential Nomination in 2008. Colorado Congressman Tom Tancredo ran on an anti-illegal immigration platform and specifically attacked sanctuary cities. Former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney accused Former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani of running it as a sanctuary city.[27] Mayor Giuliani's campaign responded saying that Governor Romney ran a sanctuary Governor's mansion, and that New York City is not a "haven" for undocumented immigrants.[27]

Following the shooting death of Kathryn Steinle in San Francisco (a sanctuary city) by an undocumented immigrant, Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton (D-NY) told CNN that "The city made a mistake, not to deport someone that the federal government strongly felt should be deported. I have absolutely no support for a city that ignores the strong evidence that should be acted on."[28] The following day, her campaign stated: "Hillary Clinton believes that sanctuary cities can help further public safety, and she has defended those policies going back years."[29]

Trump administration agenda

On March 6, 2018, the U.S. Justice Department sued California, Governor Jerry Brown, and the state’s attorney general, Xavier Becerra, over three state laws passed in recent months, saying the laws made it impossible for federal immigration officials to do their jobs and deport criminals who were born outside the United States. The Justice Department called the laws unconstitutional and asked a judge to block them. The lawsuit says the state laws “reflect a deliberate effort by California to obstruct the United States’ enforcement of federal immigration law.”[30]

The Trump administration previously released a list of immigration principles to Congress. The list included funding a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border, a crackdown on the influx of Central American minors, and curbs on federal grants to sanctuary cities.[31] A pledge to strip "all federal funding to sanctuary cities" was a key Trump campaign theme. President Trump issued an executive order which declared that jurisdictions that "refuse to comply" with 8 U.S.C. 1373—a provision of federal law on information sharing between local and federal authorities—would be ineligible to receive federal grants.[32]

States and cities have shown varying responses to the executive order. Thirty-three states introduced or enacted legislation requiring local law enforcement to cooperate with ICE officers and requests to hold non-citizen inmates for deportation. Other states and cities have responded by not cooperating with federal immigration efforts or showcasing welcoming policies towards immigrants.[32] California openly refused the administration's attempts to "clamp down on sanctuary cities". A federal judge in San Francisco agreed with two California municipalities that a presidential attempt to cut them off from federal funding for not complying with deportation requests is unconstitutional,[33] ultimately issuing a nationwide permanent injunction against the facially unconstitutional provisions of the order.[34] On March 27, 2018, the all-Republican Board of Supervisors in Orange County, California voted to join the Justice Department's lawsuit against the state.[35] In Chicago a federal judge ruled that the Trump administration may not withhold public safety grants to sanctuary cities. These decisions have been seen as a setback to the administration's efforts to force local jurisdictions to help federal authorities with the policing of illegal immigrants.[36] On July 5, 2018, a federal judge upheld two of California's Sanctuary laws, but struck down a key provision in the third.[37]

Local officials who oppose the president's policies say that complying with federal immigration officers will ruin the trust established between law enforcement and immigrant communities. Supporters of the president's policies say that protection of immigrants from enforcement makes communities less safe and undermines the rule of law.[36]

Political action

State

Opposition

Georgia banned "sanctuary cities" in 2010, and in 2016 went further by requiring local governments, in order to obtain state funding, to certify that they cooperate with federal immigration officials.[38]

Arizona, through SB 1070 (enacted in 2010), requires law enforcement officers to notify federal immigration authorities "if they develop reasonable suspicion that a person they’ve detained or arrested is in the country illegally."[39]

Tennessee state law bars "local governments or officials from making policies that stop local entities from complying with federal immigration law."[40] In 2017, legislation proposed in the Tennessee General Assembly would go further, withholding funding from local governments deemed insufficiently cooperative with the federal government.[40]

In Texas no city has formally declared "sanctuary" status, but a few do not fully cooperate with federal immigration authorities and have drawn a negative response from the legislature.[41] Bills seeking to deprive state funding from police departments and municipalities that do not cooperate with federal authorities had been introduced into the Texas Legislature several times.[41] On February 1, 2017, Texas Governor Greg Abbott blocked funding to Travis County, Texas due to its recently implemented de facto sanctuary city policy.[42][43] On May 7, 2017, Abbott signed Texas Senate Bill 4 into law, effectively banning sanctuary cities by charging county or city officials who refuse to work with federal officials and by allowing police officers to check the immigration status of those they detain if they choose.[44][45]

Support

The California state senate passed California Sanctuary Law SB54, a bill that largely prohibits local law enforcement agencies from using their money, equipment or personnel to aid federal government action against illegal immigrants.

[46]

Federal

The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 addressed the relationship between the federal government and local governments. Minor crimes, such as shoplifting, became grounds for possible deportation.[47] Additionally, the legislation outlawed cities' bans against municipal workers reporting a person's immigration status to federal authorities.[48]

Section 287(g) makes it possible for state and local law enforcement personnel to enter into agreements with the federal government to be trained in immigration enforcement and, subsequent to such training, to enforce immigration law. However, it provides no general power for immigration enforcement by state and local authorities.[49] This provision was implemented by local and state authorities in five states, California, Arizona, Alabama, Florida and North Carolina by the end of 2006.[50] On June 16, 2007 the United States House of Representatives passed an amendment to a United States Department of Homeland Security spending bill that would withhold federal emergency services funds from sanctuary cities. Congressman Tom Tancredo (R-Colo.) was the sponsor of this amendment. 50 Democrats joined Republicans to support the amendment. The amendment would have to pass the United States Senate to become effective.[51]

In 2007, Republican representatives introduced legislation targeting sanctuary cities. Reps. Brian Bilbray, R-Calif., Ginny Brown-Waite, R-Fla., Thelma Drake, R-Va., Jeff Miller, R-Fla., and Tom Tancredo introduced the bill. The legislation would make undocumented immigrant status a felony, instead of a civil offense. Also, the bill targets sanctuary cities by withholding up to 50 percent of Department of Homeland Security funds from the cities.[52]

On September 5, 2007, Department of Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff told a House committee that he certainly wouldn't tolerate interference by sanctuary cities that would block his "Basic Pilot Program" that requires employers to validate the legal status of their workers. "We're exploring our legal options. I intend to take as vigorous legal action as the law allows to prevent that from happening, prevent that kind of interference."[53][54]

On January 25, 2017 President Donald Trump signed Executive Order 13768 directing the Secretary of Homeland Security and Attorney General to defund sanctuary jurisdictions that refuse to comply with federal immigration law.[55] He also ordered the Department of Homeland Security to begin issuing weekly public reports that include "a comprehensive list of criminal actions committed by aliens and any jurisdiction that ignored or otherwise failed to honor any detainers with respect to such aliens."[55]Ilya Somin, Professor of Law at George Mason University, has argued that Trump's withholding of federal funding would be unconstitutional: "Trump and future presidents could use [the executive order] to seriously undermine constitutional federalism by forcing dissenting cities and states to obey presidential dictates, even without authorization from Congress. The circumvention of Congress makes the order a threat to separation of powers, as well."[56] On April 25, 2017, U.S. District Judge William Orrick issued a nationwide preliminary injunction halting this executive order.[57][58] The injunction was made permanent on November 20, 2017, when Judge Orrick ruled that section 9(a) of the order was "unconstitutional on its face".[59] The judgment concluded that the order violates "the separation of powers doctrine and deprives [the plaintiffs] of their Tenth and Fifth Amendment rights."[60]

In December 2018 the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals struck down a federal law that criminalized encouraging people to enter or live in the U.S. illegally. The court said the law was too broad in restricting the basic right of free speech under the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Opponents of the law argued that it was a danger to lawyers advising immigrants and to public officials who support sanctuary policies.[61][62][63]

Jurisdiction

Whether federal or local government has jurisdiction to detain and deport undocumented immigrants is a tricky and unsettled issue, because the U.S. Constitution does not provide a clear answer. Both federal and local government offer arguments to defend their authority. The issue of jurisdiction has been vigorously debated dating back to the Alien Act of 1798.[64] Opponents of local level policing tend to use the Naturalization Clause and the Migration clause in the Constitution as textual confirmation of federal power. Because the Supremacy Clause is generally interpreted to mean that federal law takes priority over state law, the U.S. Supreme Court in the majority of cases has ruled in favor of the federal government. Certain states have been affected by illegal immigration more than others and have attempted to pass legislation that limits access by undocumented immigrants to public benefits. A notable case was Arizona's SB 1070 law, which was passed in 2010 and struck down in 2012 by the Supreme Court as unconstitutional.[65]

States like Arizona, Texas and Nevada justify their aggressive actions as a result of insufficient efforts by the federal government to address issues like use of schools and hospitals by illegal immigrants and changes to the cultural landscape—impacts that are most visible on a local level.[66] Ambiguity and confusion over jurisdiction is one of the reasons why local and state policies for and against sanctuary cities vary widely depending on location in the country.

Effects

Crime

A 2017 review study of the existing literature noted that the existing studies had found that sanctuary cities either have no impact on crime or that they lower the crime rate.[5] A second 2017 study in the journal Urban Affairs Review found that sanctuary policy itself has no statistically meaningful effect on crime.[67][3][68][69][70] The findings of the study were misinterpreted by Attorney General Jeff Sessions in a July 2017 speech when he claimed that the study showed that sanctuary cities were more prone to crime than cities without sanctuary policies.[71][72] A third study in the journal Justice Quarterly found evidence that the adoption of sanctuary policies reduced the robbery rate but had no impact on the homicide rate except in cities with larger Mexican undocumented immigrant populations which had lower rates of homicide.[73]

According to a study by Tom K. Wong, associate professor of political science at the University of California, San Diego, published by the Center for American Progress, a progressive think tank: "Crime is statistically significantly lower in sanctuary counties compared to nonsanctuary counties. Moreover, economies are stronger in sanctuary counties – from higher median household income, less poverty, and less reliance on public assistance to higher labor force participation, higher employment-to-population ratios, and lower unemployment."[4] The study also concluded that sanctuary cities build trust between local law enforcement and the community, which enhances public safety overall.[74] The study evaluated sanctuary and non-sanctuary cities while controlling for differences in population, the foreign-born percentage of the population, and the percentage of the population that is Latino."[4]

Economy

Advocates of local enforcement of immigration laws argue that more regulatory local immigration policies would cause immigrants to flee those cities and possibly the United States altogether,[75] while opponents argue that regulatory policies on immigrants wouldn't affect their presence because immigrants looking for work will relocate towards economic opportunity despite challenges living there.[7] Undocumented migrants tend to be attracted to states with more economic opportunity and individual freedom.[76] Because there is no reliable data that asks for immigration status, there is no way to tell empirically if regulatory policies do have an effect on immigrant presence. A study comparing restrictive counties with nonrestrictive counties found that local jurisdictions that enacted regulatory immigration policies experienced a 1–2% negative effect in employment.[7]

Health and well-being

A preliminary study's results imply that the number of Sanctuary cities in the U.S. positively affects well-being in the undocumented immigrant population.[77] Concerning health, a study in North Carolina found that after implementation of section 287(g), prenatal Hispanic/Latina mothers were more likely than non-Hispanic/Latina mothers to have late or inadequate prenatal care. The study's interviews indicated that Hispanics/Latinos in the section 287(g) counties had distrust in health services among other services and had fear about going to the doctor.[78]

Laws and policies by state and city

Alabama

- In Alabama, state law (Alabama HB 56) was enacted in 2011, calling for proactive immigration enforcement; however, many provisions are either blocked by the federal courts or subject to ongoing lawsuits.[citation needed] On January 31, 2017, William A. Bell, the mayor of Birmingham, declared the city a "welcoming city" and said that the police would not be "an enforcement arm of the federal government" with respect to federal immigration law. He also stated that the city would not require proof of citizenship for granting business licenses. The Birmingham City Council subsequently passed a resolution supporting Birmingham being a "sanctuary city".[79]

Arizona

- Following the passage of Arizona SB 1070, a state law, few if any cities in Arizona are "sanctuary cities." A provision of SB 1070 requires local authorities to "contact federal immigration authorities if they develop reasonable suspicion that a person they've detained or arrested is in the country illegally."[39] The Center for Immigration Studies, which advocates restrictive immigration policies, labels only one city in the state, South Tucson, a "sanctuary city"; the label is because South Tucson does not honor ICE detainers "unless ICE pays for cost of detention".[39]

California

- According to the National Immigration Law Center, about a dozen California cities have some formal sanctuary policy, and none of the 58 California counties "complies with detainer requests by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement."[80]

Berkeley became the first city in the United States to pass a sanctuary resolution on November 8, 1971.[81] Additional local governments in certain cities in the United States began designating themselves as sanctuary cities during the 1980s.[82][83] Some have questioned the accuracy of the term "sanctuary city" as used in the US.[84] The policy was first initiated in 1979 in Los Angeles, to prevent the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) from inquiring about the immigration status of arrestees. Many Californian cities have adopted "sanctuary" ordinances banning city employees and public safety personnel from asking people about their immigration status.[85][86]

Coachella - 95% Latino, 2nd highest percentage Latino city in Southern California, adopted the sanctuary policy in 2015.[87]

Huntington Beach obtained a ruling from the state Supreme Court that the protections in California for immigrants who are in the country illegally do not apply to the 121 charter cities. The Orange County city is the first to successfully challenge SB 54.[88]

Los Angeles – In 1979, the Los Angeles City Council adopted Special Order 40, barring LAPD officers from initiating contact with a person solely to determine their immigration status.[89] However, the city frequently cooperates with federal immigration authorities.[80]Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti does not use the phrase "sanctuary city" to describe the city because the label is unclear.[80]

San Francisco "declared itself a sanctuary city in 1989, and city officials strengthened the stance in 2013 with its 'Due Process for All' ordinance. The law declared local authorities could not hold immigrants for immigration officials if they had no violent felonies on their records and did not currently face charges."[80] The 2015 shooting of Kathryn Steinle provoked debate about San Francisco's "sanctuary city" policy.[90]

Seaside – On March 29, 2017, Seaside became Monterey County's first sanctuary city.[91]

Williams - 75% Latino, largest percentage Latino town in Northern California, adopted the policy in 2015.[92]

- On October 5, 2017, Governor Jerry Brown signed a bill, California Sanctuary Law SB54, that makes California a "sanctuary state". It prohibits local and state agencies from cooperating with ICE regarding illegal criminals who have committed misdemeanors.[93]

Colorado

Boulder[94] became a sanctuary city in 2017.

Denver does not identify as a sanctuary city. The Denver Post reports: "The city doesn't have an ordinance staking out a claim or barring information-sharing with federal officials about a person's immigration status, unlike some cities. But it is among cities that don't enforce immigration laws or honor federal 'detainer' requests to hold immigrants with suspect legal status in jail past their release dates.[95]

Estes Park police chief Wes Kufeld stated that, "As far as day-to-day policing, people are not required to provide proof of immigration status, and our officers are not required by ICE to check immigration status, nor to conduct sweeps for undocumented individuals. So, we don’t do these things." He added that town police do assist ICE in the arrest and detainment of any illegal immigrant suspected of a felony.[96]

Connecticut

Hartford passed an ordinance providing services to all residents regardless of their immigration in 2008. Said ordinance also prohibits that police from detaining individuals based solely on their immigration status or inquiring as to their immigration status. In 2016, the ordinance was amended to declare that Hartford is a "Sanctuary City", though the term itself does not have an established legal meaning.[97]

- In 2013, Connecticut passed a law that gives local law enforcement officers discretion to carry out immigration detainer requests, though only for suspected felons.[98]

- On February 3, 2017, Middletown, CT declared itself a sanctuary city. This was in direct response to President Trump's executive order. Said Middletown's mayor, “We don't just take orders from the President of the United States”[99]

Florida

- In January 2017 Miami-Dade County rescinded a policy of insisting the U.S. government pay for detention of persons on a federal list. Republican Mayor Carlos Gimenez ordered jails to "fully cooperate" with Presidential immigration policy. He said he did not want to risk losing a larger amount of federal financial aid for not complying. The mayor said Miami-Dade County has never considered itself to be a sanctuary city.[100]

- St. Petersburg Democratic Mayor Rick Kriseman said residents from all backgrounds implored him to declare a sanctuary city. In February 2017 he blogged that, "I have no hesitation in declaring St. Petersburg a sanctuary from harmful federal immigration laws. We will not expend resources to help enforce such laws, nor will our police officers stop, question or arrest an individual solely on the basis that they may have unlawfully entered the United States." He said the county sheriff’s office has ultimate responsibility for notifying federal officials about people illegally in the city. The mayor criticized President Trump for "demonization of Muslims."[101][102]

Georgia

- The mayor of Atlanta, Georgia in January 2017 declared the city was a “welcoming city” and “will remain open and welcoming to all”. This statement was in response to President's Trump's executive orders related to “public safety agencies and the communities they serve”. Nonetheless, Atlanta does not consider itself to be a “sanctuary city”.[103] Atlanta also has refused to house new ICE detainees in its jail, but will keep the current detainees.

Illinois

Chicago became a "de jure" sanctuary city in 2012 when Mayor Rahm Emanuel and the City Council passed the Welcoming City Ordinance.[104][105] The ordinance protects residents' rights to access city services regardless of immigration status and states that Chicago police officers cannot arrest individuals on the basis of immigration status alone.[106] The status was reaffirmed in 2016.[107][108]

Urbana, Illinois[109]

Evanston, Illinois[110]

- On August 28, 2017, Illinois Governor Bruce Rauner signed a bill into law that prohibited state and local police from arresting anyone solely due to their immigration status or due to federal detainers.[111][112][113][114] Some fellow Republicans criticized Rauner for his action, claiming the bill made Illinois a sanctuary state. However, the Illinois associations for Sheriffs and Police Chiefs stated that the bill does not prevent cooperation with the federal government or give sanctuary for illegal immigrants. Both organizations support the bill.[115][116][117]

Louisiana

- In New Orleans[118] the New Orleans Police Department began a new policy to "no longer cooperate with federal immigration enforcement" beginning on Feb. 28, 2016.[118]

Maine

- A 2004 executive order prohibited state officials from inquiring about immigration status of individual seeking public assistance, but in 2011, the incoming Maine governor Paul LePage rescinded this, stating “it is the intent of this administration to promote rather than hinder the enforcement of federal immigration law”. In 2015 Governor LePage accused the city of Portland, Maine of being a sanctuary city based on the fact that “city employees are prohibited from asking about the immigration status of people seeking city services unless compelled by a court or law”,[119] but Portland city officials did not accept that characterization.[119]

Maryland

- In 2008, Baltimore and Takoma Park are sometimes identified as sanctuary cities.[120] However, "[m]ost local governments in Maryland – including Baltimore – still share information with the federal government."[121] In 2016, Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake said that she did not consider Baltimore to be a "sanctuary city."[122]

Massachusetts

Boston has an ordinance, enacted in 2014, that bars the Boston Police Department "from detaining anyone based on their immigration status unless they have a criminal warrant."[123]Cambridge, Chelsea, Somerville, Orleans, Northampton, and Springfield have similar legislation.[123] In August 2016, Boston Police Commissioner, William B. Evans re-issued a memo stating “all prisoners who are subject to ICE Detainers must receive equal access to bail commissioners, which includes notifying said prisoner of his or her right to seek bail.” Bail commissioners are informed of the person’s status on an ICE detainer list and may set bail accordingly.[124]

- The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled in 2017 that a person cannot be held solely due to an ICE detainer.[125]

Michigan

Detroit and Ann Arbor are sometimes referred to as "sanctuary cities" because they "have anti-profiling ordinances that generally prohibit local police from asking about the immigration status of people who are not suspected of any crime."[126] Unlike San Francisco's ordinance, however, the Detroit and Ann Arbor policies do not bar local authorities from cooperating and assisting ICE and Customs and Border Protection, and both cities frequently do so.

Kalamazoo re-affirmed its status as a sanctuary city in 2017. Vice Mayor Don Cooney stated, "We care about you. We will protect you. We are with you."

Lansing voted to become a sanctuary city in April 2017, but reversed the decision a week later due to public and business opposition. An order by mayor Virg Bernero still prohibits Lansing police officers from asking residents about their immigration status, however.[127]

Minnesota

Minneapolis has an ordinance, adopted in 2003,[128] that directs local law enforcement officers "not to 'take any law enforcement action' for the sole purpose of finding undocumented immigrants, or ask an individual about his or her immigration status."[129] The Minneapolis ordinance does not bar cooperation with federal authorities: "The city works cooperatively with the Homeland Security, as it does with all state and federal agencies, but the city does not operate its programs for the purpose of enforcing federal immigration laws. The Homeland Security has the legal authority to enforce immigration laws in the United States, in Minnesota and in the city."[128]

New York

Albany - Mayor Kathy Sheehan stated that the city complies with federal law and cooperates with ICE, but she asserted that comments by national government officials show a failure "to understand what is happening in our cities and why a city like Albany would choose to label itself as a sanctuary city."[130]

Ithaca[131]

New York City[132] (see also illegal immigration to New York City)- Newburgh, New York

Rochester[133]

Syracuse[134]

New Jersey

Among the municipalities which are considered sanctuary cities are Asbury Park, Camden, East Orange, Hoboken, Jersey City, Linden, New Brunswick, Newark, North Bergen, Plainfield, Trenton and Union City.[135] Those with specific executive orders made by mayors or resolution by municipal councils are:

Jersey City[136][137]

Maplewood[138]

Newark[139][140]

East Orange[141]

Prospect Park[142]

Union City[143]

Highland Park (see:Reformed Church of Highland Park)

Hoboken[144][145]

North Carolina

- The state of North Carolina currently restricts any city or municipality from refusing to cooperate with federal immigration and customs enforcement officials.[146] There are therefore no official sanctuary cities in the state. A bill, under consideration as of March 2017, is entitled Citizens Protection Act of 2017 or HB 63. Under the new provisions, the state would be able to deny bail to undocumented immigrants for whom Immigration and Customs Enforcements (ICE) has issued a detainer; allow the state to withhold tax revenues from cities who are not in compliance with the statewide immigration regulations; and encourage tipsters to identify municipalities which violate these laws.[147]

Ohio

Cincinnati's mayor declared the city a sanctuary city on January 30, 2017 in response to a federal executive order limiting immigration issued three days earlier.[148]

Oregon

- State law passed in 1987: "Oregon Revised Statute 181.850, which prohibits law enforcement officers at the state, county or municipal level from enforcing federal immigration laws that target people based on their race or ethnic origin, when those individuals are not suspected of any criminal activities.[149][150]

Beaverton city council passed a resolution in January 2017 stating, in part, "The City of Beaverton is committed to living its values as a welcoming city for all individuals ...regardless of a person's ... immigration status" and that they would abide by Oregon state law of not enforcing federal immigration laws.[151]

Corvallis[152]

Portland[153]

Pennsylvania

There are currently 18 sanctuary jurisdictions in the state of Pennsylvania.[154][155] Sanctuary jurisdictions exist in Bradford County, Bucks County, Chester County, Clarion County, Delaware County, Erie County, Franklin County, Lebanon County, Lehigh County, Lycoming County, Montgomery County, Montour County, Perry County, Philadelphia County, Pike County, and Westmoreland County.

Philadelphia mayor Jim Kenney said in November 2016 that federal immigration policies lead to more crime, and that crime rates declined the year he reinstated a sanctuary city policy.[156] U.S. Attorney General Sessions has included Philadelphia on the list of cities threatened with subpoenas if they fail to provide documents to show whether local law enforcement officers are sharing information with federal immigration authorities.[157]

Washington

Seattle[158]

Canada

Ontario

Toronto was the first city in Canada to declare itself a sanctuary city, with Toronto City Council voting 37–3 on February 22, 2013 to adopt a formal policy allowing undocumented migrants to access city services.[159]Hamilton, Ontario declared itself a sanctuary city in February 2014 after the Hamilton City Council voted unanimously to allow undocumented immigrants to access city-funded services such as shelters, housing and food banks.[160] In response to US President Donald Trump's Executive Order 13769, the city council of London, Ontario voted unanimously to declare London a sanctuary city in January 2017[161] with Montreal doing the same in February 2017 after a unanimous vote.[162]

Western Canada

While Vancouver, Canada is not a sanctuary city, it adopted an "Access to City Services without Fear" policy for residents that are undocumented or have an uncertain immigration status in April 2016.[163] The policy does not apply to municipal services operated by individual boards, including services provided by the Vancouver Police Department, Vancouver Public Library, or Vancouver Park Board.[164]

As of February 2017[update], the cities of Calgary, Ottawa, Regina, Saskatoon, and Winnipeg are considering motions to declare themselves sanctuary cities.[164][165]

As of September 9, 2018[update], Edmonton adopted "Access Without Fear" policy for undocumented and vulnerable residents.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, sanctuary cities provide services – such as housing, education, and cultural integration – to asylum seekers (i.e. persons fleeing one country and seeking protection in another).[11] The movement began in Sheffield in the north of England in 2005. It was motivated by a national policy adopted in 1999 to disperse asylum seekers to different towns and cities in the UK.

Sheffield

In 2009, the city council of Sheffield, UK drew up a manifesto outlining key areas of concern and 100 supporting organizations signed on.[166]

A city's status as a place of sanctuary is not necessarily a formal governmental designation. The organization City of Sanctuary encourages local grassroots groups throughout the UK and Ireland to build a culture of hospitality towards asylum seekers.[167]

Glasgow

Glasgow is a noted sanctuary city in Scotland. In 2000 the city council accepted their first asylum seekers relocated by the Home Office. The Home Office provided funding to support asylum seekers but would also forcibly deport them ("removal seizures") if it was determined they could not stay in the UK. As of 2010 Glasgow had accepted 22,000 asylum seekers from 75 different nations. In 2007, local residents upset by the human impact of removal seizures, organized watches to warn asylum seekers when Home Office vans were in the neighborhood. They also organized protests and vigils which led to the ending of the removal seizures.[10][13]

See also

- Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions

- Rapid response team

- Safe-haven law

- Sanctuary movement

- Sanctuary campus

References

^ "Dallas County sheriff eases immigration holds on minor offenses". The Dallas Morning News. October 11, 2015..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab Dinan, Stephen. "Half of all Americans now live in 'sanctuaries' protecting immigrants". The Washington Times. Retrieved 2018-05-10.

^ ab Loren Collingwood, Benjamin Gonzalez-O'Brien & Stephen El-Khatib Oct (October 3, 2016). "Sanctuary cities do not experience an increase in crime". Washington Post.

^ abc "The Effects of Sanctuary Policies on Crime and the Economy". Center for American Progress. January 26, 2017.

^ ab Martínez, Daniel E.; Martínez-Schuldt, Ricardo D.; Cantor, Guillermo (2017). "Providing Sanctuary or Fostering Crime? A Review of the Research on "Sanctuary Cities" and Crime". Sociology Compass. 12: e12547. doi:10.1111/soc4.12547. ISSN 1751-9020.

^ Martínez, Daniel E.; Martínez-Schuldt, Ricardo; Cantor, Guillermo (2018). "Sanctuary Cities" and Crime. pp. 270–283. doi:10.4324/9781317211563-21. ISBN 9781317211563.

^ abc Pham, Huyen; Van, Pham Hoang (November 2012). "THE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF LOCAL IMMIGRATION REGULATION: AN EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS". Cardozo Law Review. 32: 485–518.

^ Su, Rick (July 2011). "Police Discretion and Local Immigration Policymaking". UMKC Law Review. 79: 901–924.

^ Randy K. Lippert; Sean Rehaag (2013). Sanctuary Practices in International Perspectives: Migration, Citizenship, and Social Movements. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-67346-4.

^ abc Nicoll, Vivienne (25 August 2014). "City offering sanctuary to refugees from Syria". Evening Times.

^ ab Van Steenbergen, Marishka (10 May 2012). "City of Sanctuary concern for welfare of asylum seekers as housing contract goes to private security firm". The Guardian.

^ "Swansea City of Sanctuary - Building a culture of hospitality for people seeking sanctuary". swansea.cityofsanctuary.org. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

^ ab Forrest, Adam (14 June 2010). "Sanctuary City". The Big Issue.

^ ab Sanctuary City – A Suspended State – J. Bagelman – Palgrave Macmillan. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

^ Metzger, Bruce M.; Coogan, Michael D., eds. (1993). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-19-504645-8.

^ Paik, Naomi (June 2017). "Abolitionist futures and the US sanctuary movement". Sage. 59: 3–25.

^ Bracken, Amy (Dec. 29 2016). "Why You Need To Know About Guatemala's Civil War". Public Radio International.

^ Bauder, Harald(2017-04-01). "Sanctuary Cities: Politics and Practice in International Perspective. International Migration. 55.(2): 174-187. ISSN 1468-2435.

^ Cunningham, Hilary, God and Caesar at the Rio Grande: sanctuary and the politics of religion (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995),

^ Mancina, P. 2013 “The birth of a sanctuary-city: a history of governmental sanctuary in San Francisco”. In R.K. Lippert and S. Rehaag (Eds) Sanctuary Practices in International Perspectives: Migration, Citizenship and Social Movements. Abingdon, UK, Routledge: 205–218.

^ abc Emily Guskin, 'Illegal,' 'undocumented,' 'unauthorized': News media shift language on immigration", Pew Research Center (March 17, 2013).

^ "Harald Bauder" (PDF). Ryerson.ca. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

^ abcd Stephen Hiltner, Illegal, Undocumented, Unauthorized: The Terms of Immigration Reporting, New York Times (March 10, 2017).

^ ab Rui Kaneya,

'Illegal,' 'undocumented,' or something else? No clear consensus yet, Columbia Journalism Review (December 23, 2014).

^ Andrew Beaujon & Taylor Miller Thomas, AP changes style on 'illegal immigrant', Poynter Institute (April 2, 2013).

^ Derek Hawkins, The long struggle over what to call 'undocumented immigrants' or, as Trump said in his order, 'illegal aliens', Washington Post (February 9, 2017).

^ ab Tapper, Jake; Claiborne, Ron (2007-08-08). "Romney: Giuliani's NYC 'Sanctuary' for undocumented Immigrants". ABC News.

^ Eric Bradner, CNN (7 July 2015). "Clinton: 'People should and do trust me' – CNNPolitics.com". CNN. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

^ Suzanne Gamboa. "Clinton Campaign: Sanctuary Cities Can Help Public Safety". NBC News. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

^ "Trump Administration Sues California Over Immigration Laws" New York Times, March 6, 2018. Retrieved March 6, 2018

^ Nakamura, David (2017-10-08). "Trump administration releases hard-line immigration principles, threatening deal on 'dreamers'". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2017-11-21.

^ ab Chishti, Muzaffar; Pierce, Sarah (2017-04-19). "Despite Little Action Yet by Trump Administration on Sanctuary Cities, States and Localities Rush to Respond to Rhetoric". Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved 2017-11-21.

^ Phillips, Amber (2017-04-25). "Analysis | California is in a war with Trump on 'sanctuary cities.' It just won its first major battle". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2017-11-21.

^ Diamond, Jeremy; McKirdy, Euan (November 21, 2017). "Judge issues blow against Trump's sanctuary city order". CNN. Archived from the original on November 22, 2017. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

^ "Orange County Joins Fight On California Sanctuary Law". CBS SF Bay Area. 2018-03-27.

^ ab "Federal Court Says Trump Administration Can't Deny Funds To Sanctuary Cities". NPR.org. Retrieved 2017-11-21.

^ "Federal judge denies Trump administration effort to block California's 'sanctuary' law".

^ Jeremy Redmon, Are there Sanctuary Cities in Georgia?, Atlanta Journal-Constitution (February 2, 2017).

^ abc Tim Steller, Tucson a 'sanctuary city'? Not so fast, Arizona Daily Star (February 23, 2016).

^ ab Ariana Maia Sawyer, Lawmaker introduces Tennessee 'sanctuary city' ban, USA Today Network (February 8, 2017).

^ ab Doyin Oyeniyi, Does Texas Have Any Sanctuary Cities?, Texas Monthly (February 11, 2016).

^ "Texas Gov. Abbott Cuts Funding to Austin Over Sanctuary City Policies". Fox News. February 2, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

^ Svitek, Patrick (February 2, 2017). "In "Sanctuary" Fight, Abbott Cuts Off Funding to Travis County". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

^ "Texas Governor Signs Bill Targeting Sanctuary Cities". Fox News. May 7, 2017. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

^ Carter, Brandon (May 7, 2017). "Texas Governor Signs Law Banning Sanctuary Cities". The Hill. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

^ "In a Trump-defying move, California's Senate passes sanctuary state bill" CNN.com. Retrieved July 2, 2017

^ Johnson, Dawn Marie (2001). "Legislative Reform: The AEDPA and the IIRIRA: Treating Misdemeanors as Felonies for Immigration Purposes". Journal of Legislation. 27: 477.

^ Brownstein, Ron (August 22, 2007). "'Sanctuary' as battleground". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011.

^ IIRIRA 287(g)

^ Katie Zezima, Massachusetts Set for Its Officers to Enforce Immigration Law The New York Times, December 13, 2006

^ "House Passes Tancredo Immigration Amendment". PBS. June 20, 2007.

^ Moscoso, Eunice (September 18, 2007). "Legislation introduced to make illegal presence a felony; punish "sanctuary cities"". Austin American-Statesman.

^ Hudson, Audrey (September 6, 2007). "Chertoff warns meddling 'sanctuary cities'". The Washington Times. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

^ "Holding the Department of Homeland Security Responsible for Security Gaps". US House of Representatives. September 5, 2007. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

^ ab "Executive Order: Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States". WhiteHouse.gov. Retrieved January 25, 2017.,

^ "Why Trump's executive order on sanctuary cities is unconstitutional". Washington Post. Retrieved 2017-01-27.

^ Levin, Sam (April 25, 2017). "Trump's order to restrict 'sanctuary cities' funding blocked by federal judge". The Guardian. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

^ Egelko, Bob (April 25, 2017). "Judge says Trump can't punish cities over sanctuary city policies". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

^ Visser, Nick (November 21, 2017). "Judge Permanently Blocks Trump's Executive Order On Sanctuary Cities". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on November 24, 2017. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

^ County of Santa Clara v. Trump (17-cv-00485-WHO), p. 28 (N.D. Cal. November 20, 2017). Text

^ Thanawala, S. (2018, December 05). US law against encouraging illegal immigration struck down. Retrieved March 02, 2019, from https://www.apnews.com/344dab0d2df44a6f995f2773ed61f636

^ United States v. Sineneng-Smith (United States Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit December 4, 2018) (Http://cdn.ca9.uscourts.gov/datastore/opinions/2018/12/04/15-10614.pdf, Dist. file).

^ Title 8 Aliens and Nationality, U.S. Code § 1324. Bringing in and harboring certain aliens (1907).

^ Booth, Daniel. "FEDERALISM ON ICE: STATE AND LOCAL ENFORCEMENT OF FEDERAL IMMIGRATION LAW". Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy. 29: 1068.

^ Riverstone-Newell, Lori. "The Diffusion of Local Bill of Rights Resolutions to the States". Sage. 41: 14.

^ Fandl, Kevin. "Putting States Out of the Immigration Law Enforcement Business". Harvard Law & Policy Review. 9: 531.

^ Gonzalez, Benjamin; Collingwood, Loren; El-Khatib, Stephen Omar (2017-05-07). "The Politics of Refuge: Sanctuary Cities, Crime, and Undocumented Immigration". Urban Affairs Review. 55: 3–40. doi:10.1177/1078087417704974. ISSN 1078-0874.

^ "Is Philly's sanctuary city status putting residents in danger?". @politifact. Retrieved 2017-04-23.

^ "No Evidence Sanctuary Cities 'Breed Crime' - FactCheck.org". FactCheck.org. 2017-02-10. Retrieved 2017-04-23.

^ "Trump's claim that sanctuary cities 'breed crime'". Washington Post. Retrieved 2017-04-23.

^ "Analysis | Jeff Sessions used our research to claim that sanctuary cities have more crime. He's wrong". Washington Post. Retrieved 2017-07-14.

^ "Academics push back against attorney general's misrepresentation of their study". Retrieved 2017-07-17.

^ Martínez-Schuldt, Ricardo D.; Martínez, Daniel E. (2017-12-18). "Sanctuary Policies and City-Level Incidents of Violence, 1990 to 2010". Justice Quarterly. 0: 1–27. doi:10.1080/07418825.2017.1400577. ISSN 0741-8825.

^ "Crime and Poverty Are Lower in Sanctuary Cities". CityLab. Retrieved 2017-02-06.

^ Kobach, Kris W. (April 2008). "ATTRITION THROUGH ENFORCEMENT: A RATIONAL APPROACH TO ILLEGAL IMMIGRATION". Tulsa Journal of Comparative & International Law. 15: 155–163. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

^ Nair-Reichert, U. (2015). "Location decisions of undocumented migrants in the United States". Journal of Regional Analysis and Policy. 44 (2): 157–165.

^ Cebula, Richard J. (July 28, 2015). "Give me sanctuary! The impact of personal freedom afforded by sanctuary cities on the 2010 undocumented immigrant settlement pattern with the U.S., 2SLS estimates". Journal of Economics and Finance. 40 (4): 792–802. doi:10.1007/s12197-015-9333-7.

^ Rhodes, Scott D.; Mann, Lilli; Simán, Florence; et al. (2015). "The Impact of Local Immigration Enforcement Policies on the Health of Immigrant Hispanics/Latinos in the United States". American Journal of Public Health. 105 (2): 329–337. doi:10.2105/ajph.2014.302218. PMC 4318326. PMID 25521886 – via EBSCOHost.

^ Watkins, Mia. "Birmingham City Council passes sanctuary city resolution". Retrieved 20 March 2017.

^ abcd Cindy Carcamo, Kate Mather & Dakota Smith, Trump's crackdown on illegal immigration leaves a lot unanswered for sanctuary cities like L.A., Los Angeles Times (November 15, 2016).

^ "Berkeley Is The Original Sanctuary City" East Bay Express, February 14, 2017. Retrieved March 23, 2017

^ Mancina, Peter (2016). In the Spirit of Sanctuary: Sanctuary City Policy Advocacy and the Production of Sanctuary-Power in San Francisco, California (PDF). Nashville: Vanderbilt University Electronic Theses and Dissertations.

^ Mancina, Peter (2012). "The Birth of a Sanctuary City: A History of Governmental Sanctuary in San Francisco". In Lippert, Randy; Rehaag, Sean. Sanctuary Practices in International Perspectives: Migration, Citizenship, and Social Movements. New York: Routledge. pp. 205–18. ISBN 978-0-415-67346-4.

^ ""Sanctuary Cities," Trust Acts, and Community Policing Explained". American Immigration Council. 2016-07-18. Retrieved 2016-10-28.

^ "Sanctuary Cities, USA". Ohio Jobs & Justice Political Action Committee. Salvi Communications.

^ "'Sanctuary Cities' Embrace Undocumented Immigrants – Human Events". Human Events. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

^ https://www.desertsun.com/story/news/local/coachella/2017/08/23/coachella-becomes-valleys-second-sanctuary-city/595599001/

^ Vega, Priscella (September 28, 2018). "California 'sanctuary' law doesn't apply to charter cities, judge rules in Huntington Beach case". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

^ Kate Mather & Cindy Chang, LAPD will not help deport immigrants under Trump, chief says, Los Angeles Times (November 14, 2016).

^ Pearson, Michael (July 8, 2015). "What's a sanctuary city, and why should you care?". CNN. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

^ Schmalz, David. "Seaside becomes the Monterey Peninsula's first sanctuary city". MontereyCountyWeekly.com. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

^ "Maps: Sanctuary Cities, Counties, and States".

^ "California Governor Signs 'Sanctuary State' Bill" NPR. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

^ "Boulder City Council Approves Sanctuary City Status". CBS Denver. 4 January 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

^ Jon Murray (January 30, 2017). "Mayor Hancock says he welcomes "sanctuary city" title if it means Denver supports immigrants and refugees". The Denver Post.

^ "Understanding Immigration Enforcement And The Role Of The Estes Park Police". Directed from: Town of Estes Park news, April 21, 2017. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

^ "Hartford Municipal Code". www.municode.com. Retrieved 2017-03-20.

^ "Connecticut could be in crosshairs of Trump's sanctuary city crackdown". 2016-11-28. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

^ Staff, WTNH com (3 February 2017). "Mayor declares Middletown a sanctuary city". Retrieved 20 March 2017.

^ "Florida's largest county to comply with Trump's sanctuary crackdown", Ray Sanchez, CNN, 27 January 2017.

^ "Mayor declares St. Petersburg a sanctuary city" Bay News 9, February 04, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

^

"Shelter in the Sunshine City" Rick Kriseman blog. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

^ "As Trump enacts ban on refugees, Atlanta doubles down as a 'welcoming city' – SaportaReport". 30 January 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

^ Chicago code Welcoming City Ordinance Chapter 2-173, chicagocode.org (January 25, 2017).

^ Welcoming City Ordinance Chapter 2-173 Welcoming City Ordinance, City of Chicago (January 25, 2017).

^ City of Chicago Sanctuary City Supportive Resources, City of Chicago | Office of New Americans (January 25, 2017).

^ Mayor's Press Office, Mayor Emanuel Reiterates Chicago's Status as Sanctuary City, City of Chicago (November 13, 2016).

^ Richard Gonzales, Mayor Rahm Emanuel: 'Chicago Always Will Be A Sanctuary City' NPR (November 14, 2016).

^ Jeff Bossert, Sanctuary City Measure Passes Urbana Council On 5–1 Vote WILL Illinois public media news (December 20, 2016).

^ Bookwalter, Genevieve. "Evanston strengthens sanctuary city ordinance". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 2017-02-09.

^ Bernal, Rafael (August 28, 2017). "Illinois Governor Signs Immigration, Automatic Voter Registration Measures". The Hill. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

^ Geiger, Kim (August 28, 2017). "Rauner Signs Immigration, Automatic Voter Registration Bills Into Law". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

^ Runge, Erik; Associated Press (August 28, 2017). "Gov. Rauner Signs Controversial Immigration Bill". WGN-TV. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

^ Tareen, Sophia (August 28, 2017). "Governor Signs Law Limiting Illinois Police on Immigration". ABC News (from the Associated Press). Retrieved September 9, 2017.

^ Sfondeles, Tina (August 22, 2017). "Right Suggests Rauner Immigration Bill Backing 'Beginning of End'". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

^ Singman, Brooke (August 28, 2017). "GOP Gov. Rauner Accused of Making Illinois a 'Sanctuary State' with New Law". Fox News. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

^ Schoenburg, Bernard (September 4, 2017). "Some In GOP Upset with Rauner Over Immigration Bill". The State Journal-Register. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

^ ab Robert McClendon, 'Sanctuary city' policy puts an end to NOPD's immigration enforcement, NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune (March 01, 2016).

^ ab Despite LePage remark, 'sanctuary city' label doesn’t fit Portland, officials say, Randy Billings, September 15, 2015, Portland Press Herald

^ Laura Schwartzman, Legislation would ban Takoma Park sanctuary policies, Capital News Service (March 19, 2008).

^ John Fritze, House passes 'sanctuary city' bill, reigniting immigration debate, Baltimore Sun (July 23, 2016).

^ Yvonne Wenger, Mayor: Baltimore is a 'welcoming city' for immigrants and refugees, Baltimore Sun (November 16, 2016).

^ ab Kyle Scott Clauss, Boston Already Has Some Sanctuary City Protections: Thanks to the 2014 Trust Act, police can’t detain someone based on their immigration status, Boston Magazine (November 15, 2016).

^ "Cops increasingly denying requests to hold illegals". 2017-01-10. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

^ "Massachusetts Court System" (PDF).

^ Jonathan Oosting, Push to ban 'sanctuary cities' in Michigan faces criticism from immigrant advocates, MLive (September 30, 2015).

^ Lauren Gibbons, "Lansing no longer a sanctuary city"., MLive (April 12, 2017)

^ ab Ibrahim Hirsi, What the conflict over 'sanctuary cities'could mean for the Twin Cities, Minn Post (November 23, 2016).

^ Mike Mullen, Betsy Hodges: Minneapolis will remain a 'sanctuary city,' despite Trump threats, City Pages (November 14, 2016).

^ "The Justice Department is stepping up pressure on ‘sanctuary cities.’ Here’s how mayors are responding" PBS Newshour, January 24, 2018. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

^ Weinstein, Matt (February 1, 2017). "Sanctuary City: Ithaca council approves resolution". Ithaca Journal.

^ City Policy Concerning Aliens (PDF), 1989 – via Nyc.gov

^ Goodman, James (20 January 2017). "Mayor Warren to update Rochester's sanctuary city resolution". Rochester Democrat and Chronicle.

^ "In final State of the City speech, Miner declares Syracuse a sanctuary city". WRVO Public Media. 13 January 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

^ "What towns in New Jersey are considered sanctuary cities?". New Jersey 101.5 – New Jersey News Radio. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

^ Terrence T. McDonald, The Jersey Journal, November 23, 2016, (via) nj.com, Jersey City will protect immigrants from 'hate and prejudice,' councilman says, Retrieved November 24, 2016

^ Terrence T. McDonald, The Jersey Journal, NJ.com, February 2, 2017, Fulop says he will sign order making Jersey City a true 'sanctuary city', Retrieved February 4, 2017

^ Eric Kiefer, NJ Patch, January 20, 2017, (via) patch.com, Maplewood 1st N.J. Town To Offer Immigrants ‘Sanctuary’ In 2017, Retrieved January 20, 2017

^ Mazzola, Jessica. "Why these 5 N.J. 'sanctuary' communities could be targeted by Trump". NJ.com. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

^ "Newark mayor signs sweeping sanctuary city executive order". NJ.com. June 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

^ Vereau, Gery. "Orange Approves Sanctuary City Resolution". voicesofny.org. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

^ "Prospect Park Mayor Mohamed Khairullah Wins Kudos for Sanctuary City Exec Order". Observer.com. 6 February 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

^ "Union City becomes a sanctuary city Commissioners vote for designation – Union City has become the second municipality in Hudson County (after Jersey City) to designate itself a sanctuary city in the wake of Donald Trump's executive order pressuri..."

^ "Hoboken Declared 'Fair And Welcoming City' To Support Immigrants". Hoboken, NJ Patch. 2018-01-02. Retrieved 2018-06-21.

^ Bhalla, Ravi (1 January 2018). "Executive Order Declaring Hoboken a Fair and Welcoming City" (PDF). HobokenNJ.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-06-21. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

^ "NC House bill would penalize immigration sanctuary cities". newsobserver. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

^ "N.C. House Committee Advances Anti-Immigrant Measure". American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

^ "Cincinnati now a 'sanctuary city.' What's that mean?". Cincinnati.com. Retrieved 2017-01-31.

^ "Our Opinion: 'Sanctuary' cities not controversial in Oregon history". Retrieved 20 March 2017.

^ Wilson, Conrad (December 6, 2016). "Potential Oregon Ballot Measure Targets 'Sanctuary' Immigration Law". Oregon Public Broadcasting.

^ "Beaverton becomes sanctuary city". Retrieved 20 March 2017.

^ Wilson, Conrad (December 13, 2016). "Corvallis Declares Itself Sanctuary City". Oregon Public Broadcasting.

^ TEGNA. "What is a sanctuary city and what does it mean in Portland?". Retrieved 20 March 2017.

^ Copeland, Rich (2017-03-09). "PA's Sanctuary Cities". www.Witf.org.

^ "Sanctuary City Map". Center for Immigration Studies.

^ Terruso, Julia. "Kenney: Philadelphia stays a 'sanctuary city' despite Trump". The Inquirer.

^ Zapotosky, Matt (2018-01-24). "Justice Department threatens to subpoena records in escalating battle with 'sanctuary' jurisdictions". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

^ "Seattle will remain sanctuary city for immigrants despite Trump presidency, mayor says". Seattle Times. 2016-11-09., Retrieved January 23, 2017

^ Keung, Nicholas (February 22, 2013). "Toronto declared 'sanctuary city' to non-status migrants". Toronto Star. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

^ Van Dongen, Matthew (February 12, 2014). "Hamilton to become 'sanctuary city' for newcomers who fear deportation". The Hamilton Spectator.

^ Maloney, Patrick (January 31, 2017). "London, Ont. unanimously backs call to declare itself a sanctuary city against Trump". National Post. Postmedia News. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

^ Shingler, Benjamin (February 20, 2017). "Montreal becomes 'sanctuary city' after unanimous vote". CBC News. CBC. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

^ Fisher, Gavin (April 7, 2016). "Vancouver approves 'Access Without Fear' policy for undocumented immigrants". CBC News. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

^ ab Lindsay, Bethany; Eagland, Nick (February 11, 2017). "Fearing U.S. crackdown, refugees run to B.C." Times Colonist. Victoria, BC. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

^ Pike, Helen (February 28, 2017). "Nenshi looking for more information on implications of becoming a 'sanctuary city'". Metro Calgary. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

^ "John Darling, Craig Barnett, Sarah Eldridge "City of Sanctuary – a UK initiative for hospitality", Forced Migration Review, 9 October 2016" (PDF). FMReview.org. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

^ "About City of Sanctuary". Retrieved 20 March 2017.

Further reading

Laura Lopez-Sanders (2014). "Local governments and immigration". In James Ciment; John Radzilowski. American Immigration: An Encyclopedia (2nd ed.). M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 9780765682130.

- American Immigration Council: “Sanctuary” Policies: An Overview