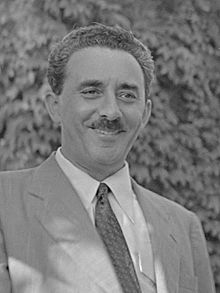

Moshe Sharett

Moshe Sharett .mw-parser-output .script-hebrew,.mw-parser-output .script-Hebr{font-size:1.15em;font-family:"Ezra SIL","Ezra SIL SR","Keter Aram Tsova","Taamey Ashkenaz","Taamey David CLM","Taamey Frank CLM","Frank Ruehl CLM","Keter YG","Shofar","David CLM","Hadasim CLM","Simple CLM","Nachlieli","SBL BibLit","SBL Hebrew",Cardo,Alef,"Noto Serif Hebrew","Noto Sans Hebrew","David Libre",David,"Times New Roman",Gisha,Arial,FreeSerif,FreeSans} משה שרת | |

|---|---|

| |

| 2nd Prime Minister of Israel | |

In office 26 January 1954 – 3 November 1955 | |

| President | Yitzhak Ben-Zvi |

| Preceded by | David Ben-Gurion |

| Succeeded by | David Ben-Gurion |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

In office 15 May 1948 – 18 June 1956 | |

| Prime Minister | David Ben-Gurion Himself David Ben-Gurion |

| Preceded by | New office |

| Succeeded by | Golda Meir |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Moshe Shertok (1894-10-15)15 October 1894 Kherson, Russian Empire |

| Died | 7 July 1965(1965-07-07) (aged 70) Jerusalem |

| Nationality | |

| Political party | Mapai |

| Spouse(s) | Tzipora Meirov (m. 1922; his death 1965) |

| Children | 3 |

| Alma mater | Istanbul University London School of Economics |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Ottoman Army |

| Rank | First Lieutenant |

| Battles/wars | World War I |

Moshe Sharett (Hebrew: משה שרת, born Moshe Shertok (Hebrew: משה שרתוק) 15 October 1894 – 7 July 1965)[1][2][3] was the second Prime Minister of Israel (1954–55), serving for a little under two years between David Ben-Gurion's two terms. He continued as Foreign Minister (1955–56) in the Mapai government.

Contents

1 Biography

2 Political career

3 Prime Minister of Israel

3.1 Lavon Affair

3.2 Principles of moderation

4 Foreign Minister

5 Retirement

6 Commemoration

7 Gallery

8 References

9 External links

Biography

Born in Kherson in the Russian Empire (today in Ukraine), Sharett immigrated to Ottoman Palestine as a child in 1906. For two years, 1906-1907, the family lived in a rented house[4] in the village of Ein-Sinya, north of Ramallah. In 1910 his family moved to Jaffa, then became one of the founding families of Tel Aviv.

He graduated from the first class of the Herzliya Hebrew High School, even studying music at the Shulamit Conservatory. He then went off to Constantinople to study law at Istanbul University, the same university at which Yitzhak Ben-Zvi and David Ben-Gurion studied. However, his time there was cut short due to the outbreak of World War I. He served a commission as First Lieutenant in the Ottoman Army, as an interpreter.[5]

In 1922, Sharett married Tzipora Meirov (12 August 1896 – 30 September 1973)[6] and had two sons and one daughter, Jacob, Yael and Chaim.

Political career

Moshe Shertok (Sharett) (standing, right) at a meeting with Arab leaders at the King David Hotel, Jerusalem, 1933. Also pictured are Haim Arlosoroff (sitting, center) with Chaim Weizmann (to his right), and Yitzhak Ben-Zvi (standing, to Shertok's right)

After the war, he worked as an Arab affairs and land purchase agent for the Assembly of Representatives of the Yishuv. He also became a member of Ahdut Ha'Avoda, and later of Mapai.[citation needed]

In 1922 he went to the London School of Economics, and while there he worked for the British Poale Zion and actively edited the Workers of Zion. One of the people he met while in London was Chaim Weizmann.[7] He then worked on the Davar newspaper from 1925 until 1931.[citation needed]

In 1931, after returning to Mandatory Palestine, he became the secretary of the Jewish Agency's political department. After the assassination of Haim Arlosoroff in 1933 he became its head.[citation needed]

During the war via his wife Zipporah, Sharett became embroiled in the question of emigration of refugee Jews stranded in Europe and the East. Some Polish refugees, children with and without parents were deported to Tehran with the Soviet's agreement. The "Tehran Children" became a cause celebre in the Yishuv. Sharett flew to Tehran to negotiate their return to Palestine. The success of these negotiations and others was a hallmark of Sharett's more cerebral approach to practical problems. He met with Tel Aviv bound Hungarian Jewish refugee representative Joel Brand, fresh off the plane from Budapest. Yishuv leadership mistrusted Brand, and the British thought him a criminal. Sharett's response was to hand the self-appointed liberator over to the British authorities, who drove Brand to prison in Egypt. Sharett's General Zionism was deeply concerned in making Palestine a commercially viable home land; secondary was the deep emotional concerns of the murder in the Diaspora which by 1942 was in German hands. Like Weizmann, whom he admired, Sharett was a principled Zionist, an implacable opponent of fascism, but a practical realist prepared to co-operate fully with the Mandate.[8]

Sharett, as Ben-Gurion's ally, denounced Irgun's assassination squads on December 13, 1947, accusing them of playing to public feelings. Atrocities escalated, mainly upon Jews, but with reciprocal revenge killings; by the end of the war 6000 Palestinian Jews, 1% of the population, had died. Sharett held the foreign policy post under the Agency until the formation of Israel in 1948.[9]

Zionist leaders, arrested in Operation Agatha, in detention in Latrun (l-r): David Remez, Moshe Sharett, Yitzhak Gruenbaum, Dov Yosef, Mr. Shenkarsky, David Hacohen, and Isser Harel (1946)

Sharett was one of the signatories of Israel's Declaration of Independence. During the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, he was Foreign Minister for the Provisional Government of Israel. Yigal Allon went to see Sharett at Tel Binyamin (Ramat Gan), his home. Allon wanted permission to capture El-Arish, destroy the base to prevent it falling into British hands. Allon could not find Ben-Gurion at Tel Aviv, because the Prime Minister was at Tiberias. But Sharett told the general that it would be unconstitutional to order an attack over the head of the Prime Minister. Moreover, it would provoke, thought Sharett the British to side with the Egyptians. When Allon explained a plan to feint an Egyptian withdrawal before invading the area between Rhaffa and Gaza, well within Israel's borders, Sharett gave it the nod. But on the telephone Ben-Gurion totally rejected the proposal. President Truman ordered troops withdrawals from the war zone, and on 1st Jan 1949, Israeli troops left Sinai and evacuated El-Arish. After a brief Egyptian counter-attack a ceasefire was called, with Egyptian troops marooned in the Faluja Pocket; Israelis had saved the Negev for good.[10]

Sharett was elected to the Knesset in the first Israeli election in 1949, and served as Minister of Foreign Affairs. On 10 March he was part of the first cabinet. A historic armistice was signed with Lebanon, so withdrawal was required from Southern Lebanon on 23 March. International negotiations hosted by Britain took place on the Greek island of Rhodes at Suneh, King Abdullah's residence when Israel's emissaries, Yigael Yadin and Walter Eytan signed with Transjordan. Knowing the Jordanian position on the Hebron Hills, Yadin told Sharett that surrounded by hostile Arab states, Israel had to sign the Transjordan over to Iraq. American Dr.Ralph Bunche, who drafted the UN treaty for Sharett's office, received the Nobel Peace Prize. The final agreement was signed at the "Grande Albergo delle Rose" in Rhodes (now the Casino Rodos) on April 3, 1949. Ominous violence lay ahead for the new state, warned Sharett during a debate on June 15, in which he reminded the Jewish people of their vital interests. A fourth and final agreement was signed with Syria on 17 July; the War of Independence had lasted one year and seven months. In the elections that followed, Labour formed a coalition, deliberately excluding Herut and the Communists at Ben-Gurion's behest.[11] As Foreign Minister, Sharett established diplomatic relations with many nations, and helped to bring about Israel's admission to the UN. He continuously held this role until he retired in June 1956 including during his period as Prime Minister.[citation needed]

In the debate on how to deal with the increasing infiltration of fedayeen across the borders in the years leading to the 1956 Suez Crisis, Sharett was sceptical of the reprisal operations being carried out by the Israeli military.[citation needed]

Sharett met with Pius XII in 1952 in an attempt to improve relations with the Holy See, although this was to no avail.[12]

Prime Minister of Israel

In January 1954 David Ben-Gurion retired from politics (temporarily as it turned out), and Sharett was chosen by the party to take his place. During his time as Prime Minister (5th and 6th governments of Israel), the Arab-Israeli conflict intensified, particularly with the Egypt of Nasser. The Lavon Affair resulting in the resignation of Pinhas Lavon, the Defense Minister, brought down the government. When David Ben-Gurion returned to the cabinet Pinchas Lavon was a civilian adviser to Prime Minister Sharett. But when he returned from the war, he was presented with a fait accompli; it had been the convention, but no longer for a career diplomat, to be chosen to become a Minister of Defense, a portfolio once controlled by the Prime Minister's office, now taken by Ben-Gurion.[citation needed]

Lavon Affair

In 1954 three cells of local Jews living in Egypt and one from Israel proper were activated as terror groups to sabotage in Alexandria and Cairo on the orders of a secretive Unit 131 of Israeli Intelligence. The Israelis welcomed the British presence in Nasser's Egypt. Israel had formed an alliance with the European powers Britain and France. Britain had helped found the State of Israel, encouraged socialism, and fostered a sense of accountable democracy. Israel viewed Britain's historic role in Cairo as a convenient buffer against potential threatening incursions into Israel's borders. A network of Israeli youth groups were ardent Zionist military trainees, but had little real experience of war. They were influenced by their charismatic leader and handler, Avri Elad. In July 1954 they threw firebomb crackers into the American libraries of Cairo and Alexandria, with little damage, and cinemas in Cairo. But 13 youths were arrested, and then tortured by the Egyptians. Two of the prisoners, including the Israeli agent Meir Max Bineth, committed suicide, and three were committed to prison. Although Sharett was the official Prime Minister, he had, according to history, not been told about the escapades (although this is unlikely, for he and Ben-Gurion were friends). He soon discovered that operations were being prepared for execution in other Arab capitals. When the news broke over Cairo Radio in summer 1954, Sharett had turned to Minister for Labour Golda Meir for help. The Minister of Defense, Pinchas Lavon, and his Head of Military Intelligence, Binyamin Gibli, both declared each other as the responsible party. The real orders were transmitted in code over the radio in the form of housewives cookery recipes.[13] Mapai was hopelessly split over the crisis. Sharett called for a Public Inquiry led by a Judge of the Supreme Court, Yitzhak Olshan, and a former Chief of Staff, Ya'akov Dori. Sharett had wanted to appoint Moshe Dayan as Minister of Defense but was aware that he was a controversial figure. There were those who defended his stubbornness as a those of a military genius, and those who saw him as divisive. But criticism of Lavon was mounting. Mapai demanded the resignation of Dayan, Gibli and Lavon. Sharett appealed to a sense of fairness from Colonel Nasser, but to no avail. A guilty verdict was entered over the heads of the prisoners in Cairo. On 31 January 1955 two of the defendants, Moshe Marzouk and Shmuel Azar were hanged, found guilty of spying. Lavon offered to resign from the department of defense on 2 February 1955, the same day Sharett and Golda Meir travelled to Sde Boker to see Ben-Gurion. Lavon's resignation was accepted on February 18. Ben-Gurion agreed to come out of retirement to fill the defense portfolio, and four months later he replaced Sharett as PM, who stayed as Foreign Minister.[14] Olshan-Dori's final judicial report exposed the difficulty of political management in the defense ministry with the cabinet conflicts emerging from Ben-Gurion's stewardship.[15]

Sharett's efforts to unblock the diplomatic impasse had failed. Nasser still prevented traffic from access to the canal. Israeli shipments of arms to defend the state dried up at a time when Arab belligerency was rising. Sharett might have learned from Weizmann's experience at befriending the consummate politician Ben-Gurion; Sharett also believed he could install him his subordinate. Ben-Gurion had been out of office for a year, but returned to demand that Dayan be reappointed. Ben-Gurion spoke regularly with socialist leaders Dayan and Shimon Peres. A few weeks later an Israeli was murdered by infiltrators across the borders. Ben-Gurion and Dayan immediately demanded approval of the planned Operation Black Arrow, which involved attacking Gaza. Sharett had attempted to be pacific and restrained during his premiership, but was overtaken by the vocal elements in Mapai and their growing electoral support in the run-up to a General election.[16]

After the military disaster at Qibya, in which Dayan had caused civilians to be killed, he was forced to change Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) policy towards targeting military installations on 28 February 1955. Sharett was concerned that casualties should be kept to an absolute minimum; 8 Israelis and 37 Egyptians [17] died in an operation that was the most bloody since the armistice of 1949. An adjutant at the ministry, Nehemia Argov, wrote to Foreign Minister and PM, Sharett to report the Gaza Raid as 8 dead and 8 wounded. The wounded were sent to Kaplan Hospital.[18]

Principles of moderation

Sharett's diary included passages in which he bewailed the senseless denigration of duty lacking credibility. He harked back to the days of Havlagah when in the 1930s both he, Sharett and Ben-Gurion had pursued a policy of self-restraint in matters military. Sharett abhorred vengeful killing, he regarded these acts as emotional over-wrought responses in which involuntary killing was devoid of moral sentiment. A policy of reprisal merely sought to justify the excessive use of force.[19] Sharett's pacific doctrine was diluted by both Ben-Gurion and Minister of Defense Dayan, and Operational commander of the Paratroop Brigade, Sharon. Sharett opposed any move that would attract moral outcry of European powers and an arms trade embargo. [20]

Foreign Minister

At the next elections in November 1955 Ben-Gurion replaced Sharett as head of the list and became prime minister again. Sharett retained his role as Foreign Minister under the new government of Ben-Gurion.[21] Ben-Gurion justified much of his policy on the siege mentality of a minority of Jews living within 57 times as many Arabs living in 215 times the land area. Sharett came to see Nasser as "suffering from delusions of grandeur" with an almost Hitlerite ambition to export revolution abroad.[22] Shimon Peres was sent to London and Paris to drum up arms. He made a significant deal with France for jets and artillery. Peres, later a Prime Minister of Israel, was praised from the Knesset for handling the complexities of the 4th Republic.[23] The uneasy diplomatic language between Nasser and Israel that had characterised the post-1949 period turned into open hostility. Nasser ended even secretive clandestine contacts. Within days of the Gaza Raid Iraq aligned in a Baghdad Pact with Turkey.[24] Ben-Gurion decided to replace Sharett as Foreign Minister with someone more sympathetic to his views - Golda Meir. The cabinet voted 35 to 7 in favour of resignation, but 75 members of the Central Committee abstained.[25] The British and French would provide a shield for Israel against sanctions. Nasser proclaimed a determination to set the Palestinians free. The Egyptian army was very certain of success; the Syrians announced a "war against imperialism, Zionism and Israel." According to Ben-Gurion the Soviet Encyclopaedia now declared the Arab-Israeli War of Independence in 1948 "was caused by American Imperialism".[citation needed]

Retirement

After stepping down as Minister of Foreign Affairs on 18 June 1956 in protest at the new government's bellicose policy that he thought was dangerously precipitate, Sharett decided to retire. Sharett had begun his career a friend of Ben-Gurion, but the two had grown apart; he had come to see him as a messianic liberator no longer prepared to negotiate, yet determined to wreak havoc on Israel's enemies. During his retirement he became chairman of Am Oved publishing house, Chairman of Beit Berl College, and Chairman of the World Zionist Organization and the Jewish Agency. He died in 1965 in Jerusalem and was buried in Tel Aviv's Trumpeldor Cemetery.[26]

Commemoration

A portrait of Moshe Sharett on the 20 New sheqalim banknote issued by the Bank of Israel.

Sharett's personal diaries, first published by his son Yaakov in 1978, have proved to be an important source for Israeli history.[27] In 2007, the Moshe Sharett Heritage Society, the foundation that Yaakov established to care for Sharett's legacy, discovered a file of thousands of passages that had been omitted from the published edition.[27] They included "shocking revelations" about the defense minister Pinhas Lavon.[28] A new edition published was complete, apart from a few words still classified.[28]

Many cities have streets and neighborhoods named after him.

Since 1988, Sharett has appeared on the 20 NIS bills. The bill first featured Sharett, with the names of his books in small print, and with a small image of him presenting the Israeli flag to the United Nations in 1949. On the back of the bill, there was an image of the Herzliya Hebrew High School, from which he graduated.[29]

In 1998 the bill went through a graphic revision, the list of Sharett's books on the front side was replaced by part of Sharett's 1949 speech in the UN. The back side now features an image of Jewish Brigade volunteers, part of a speech by Sharett on the radio after visiting the Brigade in Italy, and the list of his books in small print.[30]

Gallery

Moshe Sharett, 1936

Israeli President Chaim Weizmann (left) with first Turkish ambassador to Israel, Seyfullah Esin (c), and Foreign Minister Moshe Sharett, 1950

Amin Gargurah (left), the Mayor of Nazareth, and Moshe Sharett, 1955

References

^ "Academic American Encyclopedia". Aretê Publishing Company. 7 January 1980 – via Google Books..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "Index Sh-Sl". www.rulers.org.

^ "Knesset Member, Moshe Sharett". knesset.gov.il. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

^ "מימי הביל"ויים: יעקב שרתוק, הראשון שבראשונים". onegshabbat.blogspot.co.il.

^ "Moshe Sharett". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2012-02-21.

^ https://billiongraves.com/grave/צפורה-מאירוב-שרת/12786611#/

^ C.Shindler, A History of Modern Israel, pp. 98–9

^ Encyclopaedia of the Jewish Holocaust, vol.4, pp. 1654–5

^ "Jewish Zionist Education". Jafi.org.il. 2005-05-15. Archived from the original on 22 December 2009. Retrieved 2012-02-21.

^ M Gilbert, Israel, pp. 243–48

^ M Gilbert, Israel, pp. 260–5

^ "Israel-Vatican Diplomatic Relations". Mfa.gov.il. Retrieved 2012-02-21.

^ Gilbert, Israel, pp. 296–7

^ Gilbert, p. 255

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-23.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ "Moshe Sharett The Second Prime Minister". Pmo.gov.il. Retrieved 2012-03-08.

^ Gilbert calls the number 38 Egyptians and 2 local Arabs, p.297

^ "Moshe Sharett". Mfa.gov.il. 2003-03-02. Retrieved 2012-02-21.

^ Sharett, Yoman Ishi, 13 March 1995, p. 840; Shindler, p. 114

^ Erskine B. Childers, The Road to Suez- A study in Western-Arab relations. Macgibbon & Kee, Bristol. 1962. page 184

^ "Knesset Member, Moshe Sharett". Knesset.gov.il. Retrieved 2012-03-08.

^ Sharett, Yoman Ishi, 30 oct 1956, p. 1806 in The 1956 Sinai Campaign Viewed from Asia: Selections from Moshe Sharett's Diaries, Neil Caplan (ed.), Israel Studies vol.7 no.1, p. 89; Shindler, 115

^ Gilbert, Israel, p. 300

^ Gilbert, p. 305

^ Shindler, p. 120

^ "Where did Moshe Sharett die? - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. 1965-07-07. Retrieved 2012-02-21.

^ ab Tom Segev (23 August 2007). "Unpublished Sharett diaries dig deeper into defense minister Lavon". Haaretz.

^ ab Tom Segev (23 August 2007). "Up to no good". Haaretz.

^ "Past Notes & Coin Series". Bank of Israel. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

^ "Current Notes & Coins". Bank of Israel. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Bibliography

Bialer, Uri (1990). Between East and West: Israel's Foreign Policy Orientation, 1948-1956. London: Cambridge University Press.

Cohen, Israel (1945). The Zionist Movement. London: Frederick Muller.

Louise Fischer, ed. (2009). Moshe Sharett: The Second Prime Minister, Selected Documents (1894–1965). Jerusalem: Israel State Archives. ISBN 978-965-279-035-4.

Russell, Bertrand (1941). Zionism and the Peace Settlement in Palestine: A Jewish Commonwealth in Our Time. Washington.

Sharett, Moshe (1978). Yoman Ishi. Tel Aviv.

Sheffer, Gabriel (1996). Moshe Sharett: Biography of a Political Moderate. London and New York: Clarendon Press of Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-827994-9.

Zohar, David M. (1974). Political Parties in Israel: The Evolution of Israel's Democracy. New York.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Moshe Sharett. |

Moshe Sharett Heritage Society The official site about Moshe Sharett

Moshe Sharett Jewish Virtual Library

Moshe Sharett Jewish Agency for Israel- The Central Zionist Archives in Jerusalem site: The Office of Moshe Sharett (S65), Personal papers (A245).

- Livia Rokach: Israel's Sacred Terrorism: A Study Based on Moshe Sharett's Personal Diary and Other Documents , Foreword by Noam Chomsky, 1980.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by David Ben-Gurion | Prime Minister of Israel 1954–55 | Succeeded by David Ben-Gurion |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by David Ben-Gurion | Leader of Mapai 1954–55 | Succeeded by David Ben-Gurion |