J. Paul Getty

J. Paul Getty | |

|---|---|

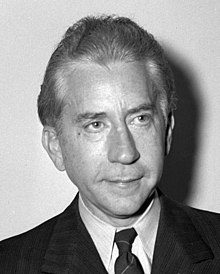

Getty in 1944 | |

| Born | Jean Paul Getty (1892-12-15)December 15, 1892 Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Died | June 6, 1976(1976-06-06) (aged 83) Sutton Place near Guildford, Surrey, England |

| Burial place | Getty Villa, Pacific Palisades, California |

| Occupation | Businessman |

| Net worth | US$6 billion at the time of his death (approximately $26.4 billion inflation adjusted, equivalent to 1/893rd of US GNP in 1976)[1] |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) |

|

Jean Paul Getty (/ˈɡɛti/; December 15, 1892 – June 6, 1976), known widely as J. Paul Getty, was a British American petrol-industrialist,[2] and the patriarch of the Getty family. He founded the Getty Oil Company, and in 1957 Fortune magazine named him the richest living American,[3] while the 1966 Guinness Book of Records named him as the world's richest private citizen, worth an estimated $1.2 billion (approximately $9.27 billion in 2018).[4] At his death, he was worth more than $6 billion (approximately $26.42 billion in 2018).[5] A book published in 1996 ranked him as the 67th richest American who ever lived, based on his wealth as a percentage of the concurrent gross national product.[6]

Despite his vast wealth, Getty was famously frugal, notably negotiating his grandson's Italian kidnapping ransom in 1973.

Getty was an avid collector of art and antiquities; his collection formed the basis of the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, California, and over $661 million (approximately $2.9 billion in 2018) of his estate was left to the museum after his death.[5] He established the J. Paul Getty Trust in 1953. The trust is the world's wealthiest art institution, and operates the J. Paul Getty Museum Complexes: The Getty Center, The Getty Villa and the Getty Foundation, the Getty Research Institute, and the Getty Conservation Institute.[7]

Contents

1 Early life and education

2 Career

2.1 Art collection

3 Marriages, divorces and children

4 Kidnapping of grandson John Paul Getty III

5 Reputation for frugality

5.1 Coin-box telephone

6 Later years & death

7 Media portrayals

8 Published works

9 See also

10 References

11 Further reading

12 External links

Early life and education

Getty was born into an Scots-Irish family in Minneapolis, Minnesota, to Sarah Catherine McPherson (Risher) and George Getty, who was an attorney in the insurance industry. Paul was raised to be a Methodist by his parents, his father was a devout Christian Scientist and both were strict teetotalers. In 1903, when Paul was 10 years old, George Getty travelled to Bartlesville, Oklahoma, and bought the mineral rights for 1,100 acres of land. Within a few years Getty had established wells on the land which were producing 100,000 barrels of crude oil a month.[8]

As newly-minted millionaires, the family moved to Los Angeles to escape the harsh Minnesota winters. At age 14 Paul attended Harvard Military School for a year, followed by Polytechnic High School, where he was given the nickname "Dictionary Getty" because of his love of reading.[9] He became fluent in French, German and Italian - over the course of his business life he would also become conversational in Spanish, Greek, Arabic and Russian. A love of the Classics also led him to acquire reading proficiency in Ancient Greek and Latin.[9] He enrolled at the University of Southern California, then at the University of California, Berkeley, but left both before obtaining a degree. Enamored with Europe after travelling abroad with his parents in 1910, on November 28, 1912, Paul enrolled at the University of Oxford. A letter of introduction by then-President of the United States William Howard Taft enabled him to gain independent instruction from tutors at Magdalen College. Although he did not belong to Magdalen, he claimed that the aristocratic students "accepted me as one of their own", and he would fondly boast of the friends he made, including Edward VIII, the future King of the United Kingdom and Emperor of India.[10] He obtained his degree in Economics and Political Science in 1914, then spent months travelling throughout Europe and Egypt, before meeting his parents in Paris and returning with them to America in June 1914.

Career

In the autumn of 1914, George Getty gave his son $10,000 to invest in expanding the family's oil field holdings in Oklahoma. The first lot he bought, the Nancy Taylor No. 1 Oil Well Site near Haskell, Oklahoma, was crucial to his early financial success. It struck oil in August 1915 and by the next summer the 40% net production royalty he accrued from it had made him a millionaire.[11]

In 1919, Getty returned to business in Oklahoma. During the 1920s, he added about $3 million to his already sizable estate. His succession of marriages and divorces (three during the 1920s, five throughout his life) so distressed his father, however, that J. Paul inherited a mere $500,000 (approximately $7.50 million in 2018) of the $10 million fortune (approximately $149.98 million in 2018) his father George had left at the time of his death in 1930. He was left with one-third of the stock from George Getty Inc., while his mother received the other two thirds, giving her a controlling interest.[12]

In 1936, his mother convinced him to contribute to the establishment of a $3.368 million (about $62.5 million in 2018) investment trust, called the Sarah C. Getty Trust, to ensure that the family's ever-growing wealth could be channeled into a tax-free, secure income for future generations of the Getty family. The trust enabled J. Paul to have easy access to ready capital, which at the time he was funneling into the purchase of Tidewater Petroleum stock.[13]

Shrewdly investing his resources during the Great Depression, Getty acquired Pacific Western Oil Corporation, and he began the acquisition (completed in 1953) of the Mission Corporation, which included Tidewater Oil and Skelly Oil. In 1967 the billionaire merged these holdings into Getty Oil.

Beginning in 1949, Getty paid Ibn Saud $9.5 million (approximately $100.04 million in 2018) in cash and $1 million a year for a 60-year concession to a tract of barren land near the border of Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. No oil had ever been discovered there, and none appeared until four years had passed, and $30 million (approximately $280.93 million in 2018) had been spent. From 1953 onward, Getty's gamble produced 16,000,000 barrels (2,500,000 m3) a year, which contributed greatly to the fortune responsible for making him one of the richest people in the world.

| The meek shall inherit the earth, but not its mineral rights. |

| — dictum attributed to Jean Paul Getty[14] |

Getty increased the family wealth, learning to speak Arabic, which enabled his unparalleled expansion into the Middle East. Getty owned the controlling interest in nearly 200 businesses, including Getty Oil. Associates identified his overall wealth at between $2 billion and $4 billion. It didn't come easily, perhaps inspiring Getty's widely quoted remark—"The meek shall inherit the earth, but not its mineral rights."[15] J. Paul Getty was an owner of Getty Oil, Getty Inc., George F. Getty Inc., Pacific Western Oil Corporation, Mission Corporation, Mission Development Company, Tidewater Oil, Skelly Oil, Mexican Seaboard Oil, Petroleum Corporation of America, Spartan Aircraft Company, Spartan Cafeteria Company, Minnehoma Insurance Company, Minnehoma Financial Company, Pierre Hotel at Fifth Avenue and East 61st Street (NYC), Pierre Marques Hotel at Revolcadero Beach near Acapulco, Mexico, a 15th-century palace and nearby castle at Ladispoli on the coast northwest of Rome, a Malibu ranch home and Sutton Place, a 72-room mansion near Guildford, Surrey, 35 miles from London.[16]

He moved to Britain in the 1950s and became a prominent admirer of England, its people, and its culture. He lived and worked at his 16th-century Tudor estate, Sutton Place; the traditional country house became the centre of Getty Oil and his associated companies and he used the estate to entertain his British and Arabian friends (including the British Rothschild family and numerous rulers of Middle Eastern countries). Getty lived the rest of his life in England, dying of heart failure at the age of 83 on June 6, 1976.

Art collection

Getty's first forays into collecting began in the late 1930s, when he took inspiration from the collection of 18th-century French paintings and furniture owned by the landlord of his New York City penthouse, Mrs. Amy Guest, a relation of Sir Winston Churchill.[17] He fell in love with 18th-century France and began buying furniture from the period at knock-down prices because of the still-depressed art market. He wrote several books on collecting: Europe and the 18th Century (1949), Collector's Choice: The Chronicle of an Artistic Odyssey through Europe (1955) and The Joys of Collecting (1965). The overwhelming goal in his collecting was to buy items at a bargain which would offer a sure return on his investment. His stinginess limited the range of his collecting because he refused to pay full-price: his companion in later life, Penelope Kitson, would comment that "Paul was really too mean ever to allow himself to buy a great painting."[18] Nonetheless, at the time of his death he owned more than 600 items valued at over $4 million (approximately $17.5 million in 2018 USD), including paintings by Rubens, Titian, Gainsborough, Renoir, Tintoretto, Degas, and Monet.[9] During the 1950s, Getty's interests shifted to Greco-Roman sculpture, which led to the building of the Getty Villa in the 1970s to house the collection.[19] These items were transferred to the Getty Museum and the Getty Villa in Los Angeles after his death.

Marriages, divorces and children

Getty was a notorious womanizer from the time of his youth, something which horrified his conservative Christian parents. His lawyer Robin Lund once said that "Paul could hardly ever say 'no' to a woman, or 'yes' to a man." [20]Lord Beaverbrook had called him "Priapic" and "ever-ready" in his sexual habits.[20]

In 1917, when he was 25, a paternity suit was filed against Getty in Los Angeles by Elsie Eckstrom, who claimed he was the father of her newborn daughter Paula.[21] Eckstrom claimed that Getty had taken her virginity and fathered the child, while his legal team tried to undermine her credibility by claiming that she had a history of promiscuity. In late 1917 he agreed to a settlement of $10,000, upon which she left town with the baby and was never heard of again.[22][23]

Getty was married and divorced five times. He had five sons with four of his wives:[5][24]

- Jeanette Demont (married 1923 – divorced 1926); one son George F. Getty II (1924–1973)

- Allene Ashby (1926–1928) no children[25] Getty met 17-year-old Ashby, the daughter of a Texas rancher, in Mexico City while he was studying Spanish and overseeing his family's business interests. They eloped to Cuernavaca, Mexico, but the marriage was bigamous as he was not yet divorced from Jeanette. The two quickly decided to dissolve the union while still in Mexico.[26]

- Adolphine Helmle (1928–1932); one son Jean Ronald Getty (1929–2009), whose son, Christopher Ronald Getty, married Pia Miller, sister of Marie-Chantal, Crown Princess of Greece. Like his first and second wives, Adolphine was 17 years-old when Getty met her on holiday in Vienna. Helmle was the daughter of a prominent German doctor, who was strongly opposed to her marrying the twice-divorced, 36-year-old Getty.[27] The two eloped to Cuernavaca, where he had married Allene Ashby, then settled in Los Angeles. Following the birth of their son, Getty lost interest in her and her father convinced her to return to Germany with their child in 1929. After a protracted and contentious battle, the divorce was finalized in August 1932, with Adolphine receiving a huge sum for punitive damages and full custody of Ronald.[28]

Ann Rork (1932–1936); two sons Eugene Paul Getty, later John Paul Getty Jr (1932–2003) and Gordon Peter Getty (born 1934). Getty was introduced to Rork when she was 14 years old, but she didn't become his romantic partner until she was 21 in 1930. Because he was in the midst of his divorce from Adolphine, the couple had to wait two years before they married. He was largely absent during their marriage, staying for long stretches of time in Europe. In 1936 she sued him for divorce, alleging emotional abuse and neglect. She also described an incident while the two were abroad in Italy, in which she claimed Getty had forced her to climb to view the crater of Mount Vesuvius while she was heavily pregnant with their first son.[29] The court decided in her favor and she was awarded $2,500 per month alimony plus $1,000 each in child support for her sons.[29]

Louise Dudley "Teddy" Lynch (1939–1958); one son Timothy Ware Getty (1946–1958)

At age 99, in 2013, Getty's fifth wife, Louise—now known as Teddy Getty Gaston—published a memoir reporting how Getty had scolded her for spending money too freely in the 1950s on the treatment of their six-year-old son, Timmy, who had become blind from a brain tumor. Timmy died at age 12, and Getty, living in England apart from his wife and son back in the U.S., did not attend the funeral. Teddy divorced him that year.[30] Teddy Gaston died in April 2017 at the age of 103.[31]

Getty was quoted as saying "A lasting relationship with a woman is only possible if you are a business failure",[24] and "I hate to be a failure. I hate and regret the failure of my marriages. I would gladly give all my millions for just one lasting marital success."[32]

Kidnapping of grandson John Paul Getty III

On July 10, 1973, in Rome, 'Ndrangheta kidnappers abducted Getty's 16-year-old grandson, John Paul Getty III, and demanded by telephone a $17 million payment (approximately $95.9 million in 2018) for the young man's safe return. However, "the family suspected a ploy by the rebellious teenager to extract money from his miserly grandfather."[33]John Paul Getty Jr. asked his father for the money, but was refused.[34]

In November 1973, an envelope containing a lock of hair and a human ear arrived at a daily newspaper. The second demand had been delayed three weeks by an Italian postal strike.[33] The demand threatened that Paul would be further mutilated unless the victims paid $3.2 million (approximately $18.1 million in 2018): "This is Paul's ear. If we don't get some money within 10 days, then the other ear will arrive. In other words, he will arrive in little bits."[33]

When the kidnappers finally reduced their demands to $3 million (approximately $16.9 million in 2018), Getty senior agreed to pay no more than $2.2 million (approximately $12.4 million in 2018) – the maximum that would be tax-deductible. He lent his son the remaining $800,000 (approximately $4.5 million in 2018) at 4% interest. Paul III was found alive in a Lauria filling station, in the province of Potenza, shortly after the ransom was paid.[35] After his release Paul III called his grandfather to thank him for paying the ransom but, it is claimed, Getty refused to come to the phone.[36] Nine people associated with 'Ndrangheta were later arrested for the kidnapping, but only two were convicted.[36] Paul III was permanently affected by the trauma and became a drug addict. After a stroke brought on by a cocktail of drugs and alcohol in 1981, Paul III was rendered speechless, nearly blind and partially paralyzed for the rest of his life. He died 30 years later on February 5, 2011, at the age of 54.[36]

Getty defended his initial refusal to pay the ransom on two points. First, he argued that to submit to the kidnappers' demands would immediately place his other fourteen grandchildren at the risk of copy-cat kidnappers. He added:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

The second reason for my refusal was much broader-based. I contend that acceding to the demands of criminals and terrorists merely guarantees the continuing increase and spread of lawlessness, violence and such outrages as terror-bombings, "skyjackings" and the slaughter of hostages that plague our present-day world. (Getty, 1976, p. 139).

Reputation for frugality

Many anecdotal stories exist of Getty's reputed thriftiness and parsimony, which struck observers as comical, even perverse, because of his extreme wealth.[37] The two most widely known examples are his reluctance to pay his grandson's $17 million Italian kidnapping ransom, and the notorious pay-phone which he had installed at Sutton Place. A darker incident was his fifth wife's claim that Getty had scolded her for spending too much on their terminally ill son's medical treatment, though he was worth tens of millions of dollars at the time.[37] He was well known for bargaining on almost everything to obtain a rock-bottom price, including suites at luxury hotels and virtually all purchases like art work and real estate. Sutton Place, for instance, a 72-room mansion, was purchased from George Sutherland-Leveson-Gower, 5th Duke of Sutherland in 1959 for the extremely low price of ₤60,000, about half of what the Duke had paid when he bought it 40 years earlier.[38]

- His secretary claimed that Getty did his own laundry by hand, because he didn't want to pay for his clothes to be laundered, and when his shirts would become frayed at the cuffs, he would simply trim off the frayed part instead of purchasing new shirts.[39]

- Re-using stationery was another obsession of Getty's. He had a habit of writing responses to letters on the margins or back sides and mailing them back, rather than use a new sheet of paper. He also carefully saved and re-used manila envelopes, rubber bands, and other office supplies.[40]

- When Getty took a group of friends to a dog show in London, he made them walk around the block for 10 minutes until the tickets became half-priced at 5 pm, because he didn't want to pay the full 5 shillings per head (about ₤12/$17 in 2018).[37]

- His decision to move to Sutton Place was made in part because the cost of living was cheaper than in London, where he had resided at the Ritz. He once boasted to American columnist Art Buchwald that it cost 10 cents for a rum and coke at Sutton Place, whereas at the Ritz it was over a dollar.[37]

Author John Pearson attributed part of this extreme penny-pinching to the Methodist sensibility of Getty's upbringing, which emphasized modest living and personal economy. His business-like attention to the bottom-line was also a major factor: "He would allow himself no self-indulgence in the purchase of a place to live, a work of art, even a piece of furniture, unless he could convince himself that it would appreciate in value."

[41] Getty himself claimed that his frugality towards others was a response to people taking advantage of him and not paying their fair share: "It's not the money I object to, it's the principle of the thing that bothers me ..."[9]

Coin-box telephone

Getty famously had a pay phone installed at Sutton Place, helping to seal his reputation as a miser.[42] Getty placed dial-locks on all the regular telephones, limiting their use to authorized staff, and the coin-box telephone was installed for others. In his autobiography, he described his reasons:

Now, for months after Sutton Place was purchased, great numbers of people came in and out of the house. Some were visiting businessmen. Others were artisans or workmen engaged in renovation and refurbishing. Still others were tradesmen making deliveries of merchandise. Suddenly, the Sutton Place telephone bills began to soar. The reason was obvious. Each of the regular telephones in the house has direct access to outside lines and thus to long-distance and even overseas operators. All sorts of people were making the best of a rare opportunity. They were picking up Sutton Place phones and placing calls to girlfriends in Geneva or Georgia and to aunts, uncles and third cousins twice-removed in Caracas and Cape Town. The costs of their friendly chats were, of course, charged to the Sutton Place bill.[43]

When speaking in a televised interview with Alan Whicker in February 1963,[44] Getty said that he thought guests would want to use a payphone.[45] After 18 months, Getty explained, "The in-and-out traffic flow at Sutton subsided. Management and operation of the house settled into a reasonable routine. With that, the pay-telephone [was] removed, and the dial-locks were taken off the telephones in the house."[46]

Later years & death

On June 30, 1960, Getty threw a 21st birthday party for a relation of his friend, the 16th Duke of Norfolk, which served as a housewarming party for the newly-purchased Sutton Place.[47] 1,200 guests consisting of the cream of British society were invited. Party goers were irritated by Getty's stinginess, such as not providing cigarettes and relegating everyone to using creosote portable toilets outside. At about 10pm the party descended into pandemonium as party crashers arrived from London, swelling the already overcrowded halls, causing an estimated ₤20,000 in damages.[47] A valuable silver ewer by the 18th century silversmith Paul de Lamerie was stolen, but returned anonymously when the London newspapers began covering the theft.[48] The failure of the event made the newly-arrived Getty the object of ridicule, and he never threw another large party again.

Getty remained an inveterate hard worker, boasting at age 74 that he often worked 16 to 18 hours per day overseeing his operations across the world.[9] The Arab-Israeli Yom Kippur War of October 1973 caused a worldwide oil shortage for years to come. In this period, the value of Getty Oil shares quadrupled, with Getty enjoying personal earnings of $25.8 million in 1975 ($120 million in 2018 USD).[49]

His insatiable appetite for women and sex also continued well into his 80s. He used an experimental drug, "H3", to maintain his potency.[20] Getty met the English interior designer Penelope Kitson in the 1950s and entrusted her with decorating his homes and the public rooms of the oil tankers he was launching. From 1960 she resided in a cottage on the grounds of Sutton Place, and, though she did not have a sexual relationship with him, Getty held her in high respect and trust. Other mistresses who resided at Sutton Place included the married Mary Teissier, a distant cousin of the last Tsar of Russia, Lady Ursula d'Abo, who had close connections to the British Royal Family, and Nicaraguan-born Rosabella Burch.[20]

The New York Times wrote of Getty's domestic arrangement that: "[Getty] ended his life with a collection of desperately hopeful women, all living together in his Tudor mansion in England, none of them aware that his favorite pastime was rewriting his will, changing his insultingly small bequests: $209 a month to one, $1,167 to another."[50] Only Penelope Kitson received a handsome bequest upon Getty's death: 5,000 Getty Oil shares (appr. $826,500 in 1976), which doubled in value during the 1980s, and a $1,167 monthly income.[20]

Getty died June 6, 1976, in Sutton Place near Guildford, Surrey, England.[2] He was buried in Pacific Palisades, Los Angeles County, California at the Getty Villa. The gravesite is not open to the public.[51]

Media portrayals

The 2017 film All the Money in the World – directed by Ridley Scott and adapted from the book Painfully Rich: The Outrageous Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Heirs of J. Paul Getty by John Pearson – is a dramatisation of the abduction of Getty's grandson. Kevin Spacey originally portrayed Getty. However, after multiple sexual assault allegations against the actor, his scenes were cut and re-shot with Christopher Plummer,[52] who was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for the performance.[53]

The kidnapping is also dramatized in the first season of the American anthology drama series Trust, in which Getty is portrayed by Donald Sutherland.[54]

Published works

- Getty, J. Paul. The history of the bigger oil business of George F.S. F. and J. Paul Getty from 1903 to 1939. Los Angeles?, 1941.

- Getty, J. Paul. Europe in the Eighteenth Century. [Santa Monica, Calif.]: privately printed, 1949.

- Le Vane, Ethel, and J. Paul Getty. Collector's Choice: The Chronicle of an Artistic Odyssey through Europe. London: W.H. Allen, 1955.

- Getty, J. Paul. My Life and Fortunes. New York: Duell, Sloan & Pearce, 1963.

- Getty, J. Paul. The Joys of Collecting. New York: Hawthorn Books, 1965.

- Getty, J. Paul. How to be Rich. Chicago: Playboy Press, 1965.

- Getty, J. Paul. The Golden Age. New York: Trident Press, 1968.

- Getty, J. Paul. How to be a Successful Executive. Chicago: Playboy Press, 1971.

- Getty, J. Paul. As I See It: The Autobiography of J. Paul Getty. Englewood Cliffs, N.J. : Prentice-Hall, 1976. .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 0-13-049593-X.

See also

- Getty family

- List of wealthiest historical figures

- List of richest Americans in history

References

^ Klepper, Michael; Gunther, Michael (1996), The Wealthy 100: From Benjamin Franklin to Bill Gates—A Ranking of the Richest Americans, Past and Present, Secaucus, New Jersey: Carol Publishing Group, p. xiii, ISBN 978-0-8065-1800-8, OCLC 33818143

^ ab Whitman, Alden (June 6, 1976). "J. Paul Getty Dead at 83; Amassed Billions From Oil". On This Day. The New York Times. New York City: New York Times Company. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016.

^ Lubar, Robert (March 17, 1986). "The Odd Mr. Getty: The possibly richest man in the world was mean, miserly, sexy, fearful of travel and detergents". Fortune. New York City: Meredith Corporation. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

^ McWhirter, Norris; McWhirter, Ross (1966). Guinness Book of Records. London, England: Jim Pattison Group. p. 229.

^ abc Lenzner, Robert. The great Getty: the life and loves of J. Paul Getty, richest man in the world. New York: Crown Publishers, 1985.

ISBN 0-517-56222-7

^ Klepper, Michael M.; Gunther, Robert E. (1996). The wealthy 100: from Benjamin Franklin to Bill Gates: a ranking of the richest Americans, past and present. Secaucus, New Jersey: Carol Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8065-1800-6.

^ Wyatt, Edward (April 30, 2009). "Getty Fees and Budget Reassessed". The New York Times. New York City: New York Times Company. p. C1. Archived from the original on February 6, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

^ John Pearson (1995). Painfully Rich. Harper Collins. p. 20.

^ abcde Alden Whitman (June 6, 1976). "J. Paul Getty Dead at 83; Amassed Billions from Oil". New York Times. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

^ Pearson, John (1995). Painfully Rich. New York City: Harper Collins. p. 29.

^ John Pearson (1995). Painfully Rich. Harper Collins. p. 34.

^ John Pearson (1995). Painfully Rich. Harper Collins. p. 47.

^ John Pearson (1995). Painfully Rich. Harper Collins. p. 63–5.

^ Manser, Martin H. (April 2007). The Facts on File dictionary of proverbs. Infobase Publishing. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-8160-6673-5. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

^ "Thoughts On The Business Of Life" Archived July 12, 2010, at the Wayback Machine at Forbes

^ Farnsworth, Clyde H. (July 30, 1964). "Surrey Estate Seat of Getty Empire". The New York Times. New York City: New York Times Company. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

^ John Pearson (1995). Painfully Rich. Harper Collins. p. 72.

^ John Pearson (1995). Painfully Rich. Harper Collins. p. 84.

^ John Pearson (1995). Painfully Rich. Harper Collins. p. 86–7.

^ abcde Miller, Julie (March 25, 2018). "Yes, J. Paul Getty Reportedly Had as Many Live-In Girlfriends as FX's Trust Claims". Vanity Fair. New York City: Condé Nast. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

^ Pearson, John (1995). Painfully Rich. New York City: Harper Collins. p. 36–7.

^ Pearson, John (1995). Painfully Rich. New York City: Harper Collins. p. 37.

^ Bevis Hillier (March 26, 1986). "The Great Getty : THE LIFE AND LOVES OF J. PAUL GETTY--RICHEST MAN IN THE WORLD by Robert Lenzner (Crown: $18.95; 304 pp.) : THE HOUSE OF GETTY by Russell Miller (Henry Holt: $17.65; 362 pp.)". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 6, 2018. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

^ ab Vallely, Paul (July 19, 2007). "Don't keep it in the family". The Independent. London, England: Independent Print Ltd. Archived from the original on December 26, 2010 – via The Wayback Machine.

^ Getty, Jean Paul (1976). As I see it: the autobiography of J. Paul Getty. Los Angeles, California: Getty Publications. p. 91. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

^ Pearson, John (1995). Painfully Rich. New York City: Harper Collins. p. 42.

^ Pearson, John (1995). Painfully Rich. New York City: Harper Collins. p. 45.

^ John Pearson (1995). Painfully Rich. Harper Collins. p. 48,59–60.

^ ab John Pearson (1995). Painfully Rich. Harper Collins. p. 71.

^ Newman, Judith (August 30, 2013). "His Favorite Wife: 'Alone Together,' by Teddy Getty Gaston". The New York Times. New York City: New York Times Company. Archived from the original on September 2, 2013. Retrieved August 31, 2013.

^ Miller, Mike (April 10, 2017). "J. Paul Getty's Ex-Wife Teddy Getty Gaston Dies at 103". People. New York City: Meredith Corporation. Archived from the original on September 13, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

^ Bloom, Linda; Bloom, Charlie (April 24, 2012). "The Price of Success". Psychology Today. New York City: Sussex Publishers. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

^ abc "Sir Paul Getty (obituary)". Daily Telegraph. London, England: Telegraph Media Group. April 17, 2003. Archived from the original on March 26, 2009. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

^ "Profile: Sir John Paul Getty II". London, England: BBC News. June 13, 2001. Archived from the original on February 18, 2007. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

^ "Il rapimento di Paul Getty". Il Post (in Italian). July 10, 2013. Archived from the original on March 30, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

^ abc Weber, Bruce (February 7, 2011). "J. Paul Getty III, 54, Dies; Had Ear Cut Off by Captors". The New York Times. New York City: New York Times Company. Archived from the original on March 24, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

^ abcd Nicolaou, Elana (March 25, 2018). "Was J Paul Getty Really THAT Cheap?". New York City: Refinery29.com. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

^ John Pearson (1995). Painfully Rich. Harper Collins. p. 113.

^ Jackson, Debbie (December 10, 2017). "Throwback Tulsa: Billionaire J. Paul Getty got his start in Tulsa". Tulsa World. Tulsa, Oklahoma: BH Media. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

^ John Pearson (1995). Painfully Rich. Harper Collins. p. 69, 121.

^ John Pearson (1995). Painfully Rich. Harper Collins. p. 42.

^ Miller, Julie (December 22, 2017). "The Enigma of J. Paul Getty, the One-Time Richest Man in the World". Vanity Fair. New York City: Condé Nast. Archived from the original on April 27, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

^ Getty, 1976, pg.319

^ "The Solitary Billionaire J. Paul Getty". Talk at the BBC. BBC. Archived from the original on March 19, 2012. Retrieved April 6, 2012.

^ Talk at the BBC, BBC Four, April 5, 2012

^ Getty, 1976, p. 320

^ ab John Pearson (1995). Painfully Rich. Harper Collins. p. 119.

^ Anthony Haden-Guest (September 27, 2015). "How Wild Was J. Paul Getty's Notorious British Party?". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on September 20, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

^ John Pearson (1995). Painfully Rich. Harper Collins. p. 199.

^ O'Reilly, Jane (March 30, 1986). "Isn't It Funny What Money Can Do?". The New York Times. New York City: New York Times Company. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

^ "J. Paul Getty (1892 - 1976)". Find a Grave.

^ Giardina, Carolyn (December 18, 2017). "Ridley Scott Reveals How Kevin Spacey Was Erased From 'All the Money in the World'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

^ "Oscars: 'Shape of Water' Leads With 13 Noms". The Hollywood Reporter. January 23, 2018. Archived from the original on January 23, 2018. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

^ Petski, Denise (January 5, 2018). "FX Sets 'Atlanta' & 'The Americans' Return Dates, 'Trust' Premiere – TCA". Deadline. Penske Business Media, LLC. Archived from the original on January 6, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

Further reading

- Hewins, Ralph. The Richest American: J. Paul Getty. New York: Dutton, 1960.

- Lund, Robina. The Getty I Knew. Kansas City: Sheed Andrews and McMeel, 1977.

ISBN 0-8362-6601-3. - Miller, Russell. The House of Getty. New York: Henry Holt, 1985.

ISBN 0-8050-0023-2.

de Chair, Somerset Struben. Getty on Getty: a man in a billion. London: Cassell, 1989.

ISBN 0-304-31807-8.- Pearson, John. Painfully Rich: J. Paul Getty and His Heirs. London: Macmillan, 1995.

ISBN 0-333-59033-3. - Wooster, Martin Morse. Philanthropy Hall of Fame, J. Paul Getty. philanthropyroundtable.org.

External links

J. Paul Getty diaries, 1938–1946, 1948–1976 finding aid, Getty Research Institute.

J. Paul Getty family collected papers, 1880s–1989, undated (bulk 1911–1977) finding aid, Getty Research Institute.