Chinese bronze inscriptions

| Chinese bronze inscriptions | |||||||||||||||||

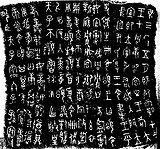

Inscription on the Song ding, c. 800 BC | |||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 金文 | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literal meaning | Bronze writing | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 鐘鼎文 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 钟鼎文 | ||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Bell and cauldron writing | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Chinese bronze inscriptions, also commonly referred to as Bronze script or Bronzeware script, are writing in a variety of Chinese scripts on Chinese ritual bronzes such as zhōng bells and dǐng tripodal cauldrons from the Shang dynasty (2nd millennium BC) to the Zhou dynasty (11th – 3rd century BC) and even later. Early bronze inscriptions were almost always cast (that is, the writing was done with a stylus in the wet clay of the piece-mold from which the bronze was then cast), while later inscriptions were often engraved after the bronze was cast.[1] The bronze inscriptions are one of the earliest scripts in the Chinese family of scripts, preceded by the oracle bone script.

Contents

1 Terminology

2 Inscribed bronzes

3 Shang bronze inscriptions

4 Zhou dynasty inscriptions

4.1 Western Zhou

4.2 Eastern Zhou

4.2.1 Spring and Autumn

4.2.2 Warring States period

5 Computer encoding

6 See also

7 Notes

8 References

9 External links

Terminology

Highly pictorial Shang clan emblem character (牛 niú "ox")

For the early Western Zhou to early Warring States period, the bulk of writing which has been unearthed has been in the form of bronze inscriptions.[a] As a result, it is common to refer to the variety of scripts of this period as "bronze script", even though there is no single such script. The term usually includes bronze inscriptions of the preceding Shang dynasty as well.[b]

However, there are great differences between the highly pictorial Shang emblem (aka "identificational") characters on bronzes (see "ox" clan insignia above), typical Shang bronze graphs, writing on bronzes from the middle of the Zhou dynasty, and that on late Zhou to Qin, Han and subsequent period bronzes. Furthermore, starting in the Spring and Autumn period, the writing in each region gradually evolved in different directions, such that the script styles in the Warring States of Chu, Qin and the eastern regions, for instance, were strikingly divergent. In addition, artistic scripts also emerged in the late Spring and Autumn to early Warring States, such as Bird Script (鳥書 niǎoshū), also called Bird Seal Script (niǎozhuàn 鳥篆 ), and Worm Script (chóngshū 蟲書).

- 寅 Yín in Four Different Scripts on Shang–Zhou bronzes

Shang Dynasty

Late Western Zhou

Bird Script, early Warring States

Late Warring States

Inscribed bronzes

Left: Bronze fāng zūn ritual wine container, c. 1000 BCE. The inscription commemorates a gift of cowrie shells to its owner. Right: Bronze fāng yí ritual container c. 1000 BCE. An inscription of some 180 characters appears twice on it, commenting on state rituals that accompany court ceremony, recorded by an official scribe.

Of the abundant Chinese ritual bronze artifacts extant today, about 12,000 have inscriptions.[2] These have been periodically unearthed ever since their creation, and have been systematically collected and studied since at least the Song dynasty.[3] The inscriptions tend to grow in length over time, from only one to six or so characters for the earlier Shang examples, to forty or so characters in the longest, late-Shang case,[3] and frequently a hundred or more on Zhou bronzes, with the longest up to around 500.[c]

In general, characters on ancient Chinese bronze inscriptions were arranged in vertical columns, written top to bottom, in a fashion thought to have been influenced by bamboo books, which are believed to have been the main medium for writing in the Shang and Zhou dynasties.[4][5] The very narrow, vertical bamboo slats of these books were not suitable for writing wide characters, and so a number of graphs were rotated 90 degrees; this style then carried over to the Shang and Zhou oracle bones and bronzes. Examples:

Examples of bronze inscription graphs rotated 270°: From left, mǎ 馬 "horse"; hǔ 虎 "tiger", shĭ 豕 "swine", quǎn 犬 "dog", xiàng 象 "elephant", guī 龜 "turtle", wèi 為 "to lead" (now "do"), jí 疾 "illness".

Of the 12,000 inscribed bronzes extant today, roughly 3,000 date from the Shang dynasty, 6,000 from the Zhou dynasty, and the final 3,000 from the Qin and Han dynasties.[2]

Shang bronze inscriptions

Inscriptions on Shang bronzes are of a fairly uniform style, making it possible to discuss a "Shang bronze script", although great differences still exist between typical characters and certain instances of clan names or emblems. Like early period oracle bone script, the structures and orientations of individual graphs varied greatly in the Shang bronze inscriptions, such that one may find a particular character written differently each time rather than in a standardized way (see the many examples of "tiger" graph to the lower left).

hǔ 虎 "tiger" from bronze inscriptions (in green), compared to other script forms

As in the oracle bone script, characters could be written facing left or right, turned 90 degrees, and sometimes even flipped vertically, generally with no change in meaning.[6] For instance, ![]() and

and ![]() both represent the modern character xū 戌 (the 11th Earthly Branch), while

both represent the modern character xū 戌 (the 11th Earthly Branch), while ![]() and

and ![]() are both hóu 侯 "marquis". This was true of normal as well as extra complex identificational graphs, such as the hǔ 虎 "tiger" clan emblem at right, which was turned 90 degrees clockwise on its bronze.

are both hóu 侯 "marquis". This was true of normal as well as extra complex identificational graphs, such as the hǔ 虎 "tiger" clan emblem at right, which was turned 90 degrees clockwise on its bronze.

These inscriptions are almost all cast (as opposed to engraved),[7] and are relatively short and simple. Some were mainly to identify the name of a clan or other name,[8] while typical inscriptions include the maker's clan name and the posthumous title of the ancestor who is commemorated by the making and use of the vessel.[9] These inscriptions, especially those late period examples identifying a name,[8] are typically executed in a script of highly pictographic flavor, which preserves the formal, complex Shang writing as would have primarily been written on bamboo or wood books,[10][d] as opposed to the concurrent simplified, linearized and more rectilinear form of writing as seen on the oracle bones.[11]

A few Shang inscriptions have been found which were brush-written on pottery, stone, jade or bone artifacts, and there are also some bone engravings on non-divination matters written in a complex, highly pictographic style;[8] the structure and style of the bronze inscriptions is consistent with these.[10]

The soft clay of the piece-molds used to produce the Shang to early Zhou bronzes was suitable for preserving most of the complexity of the brush-written characters on such books and other media, whereas the hard, bony surface of the oracle bones was difficult to engrave, spurring significant simplification and conversion to rectilinearity. Furthermore, some of the characters on the Shang bronzes may have been more complex than normal due to particularly conservative[12] usage in this ritual medium, or when recording identificational inscriptions (clan or personal names); some scholars instead attribute this to purely decorative considerations. Shang bronze script may thus be considered a formal script, similar to but sometimes even more complex than the unattested daily Shang script on bamboo and wood books and other media, yet far more complex than the Shang script on the oracle bones.

Zhou dynasty inscriptions

Western Zhou

Western Zhou dynasty characters (as exemplified by bronze inscriptions of that time) basically continue from the Shang writing system; that is, early W. Zhou forms resemble Shang bronze forms (both such as clan names,[e] and typical writing), without any clear or sudden distinction. They are, like their Shang predecessors in all media, often irregular in shape and size, and the structures and details often vary from one piece of writing to the next, and even within the same piece. Although most are not pictographs in function, the early Western Zhou bronze inscriptions have been described as more pictographic in flavor than those of subsequent periods. During the Western Zhou, many graphs begin to show signs of simplification and linearization (the changing of rounded elements into squared ones, solid elements into short line segments, and thick, variable-width lines into thin ones of uniform width), with the result being a decrease in pictographic quality, as depicted in the chart below.

Linearization of characters during the Western Zhou

Some flexibility in orientation of graphs (rotation and reversibility) continues in the Western Zhou, but this becomes increasingly scarce throughout the Zhou dynasty.[13] The graphs start to become slightly more uniform in structure, size and arrangement by the time of the third Zhou sovereign, King Kāng, and after the ninth, King Yì, this trend becomes more obvious.[14]

Some have used the problematic term "large seal" (大篆 dàzhuàn) to refer to the script of this period. This term dates back to the Han dynasty,[15] when (small) seal script and clerical script were both in use. It thus became necessary to distinguish between the two, as well as any earlier script forms which were still accessible in the form of books and inscriptions, so the terms "large seal" (大篆 dàzhuàn) and "small seal" (小篆 xiǎozhuàn, aka 秦篆 Qín zhuàn) came into being. However, since the term "large seal" is variously used to describe zhòuwén (籀文) examples from the ca. 800 BCE Shizhoupian compendium, or inscriptions on both late W. Zhou bronze inscriptions and the Stone Drums of Qin, or all forms (including oracle bone script) predating small seal, the term is best avoided entirely.[16]

Eastern Zhou

Spring and Autumn

By the beginning of the Eastern Zhou, in the Spring and Autumn period, many graphs are fully linearized, as seen in the chart above; additionally, curved lines are straightened, and disconnected lines are often connected, with the result of greater convenience in writing, but a marked decrease in pictographic quality.[11]

In the Eastern Zhou, the various states initially continued using the same forms as in the late Western Zhou. However, regional forms then began to diverge stylistically as early as the Spring and Autumn period,[17] with the forms in the state of Qin remaining more conservative. At this time, seals and minted coins, both probably primarily of bronze, were already in use, according to traditional documents, but none of the extant seals have yet been indisputably dated to that period.[18]

By the mid to late Spring and Autumn period, artistic derivative scripts with vertically elongated forms appeared on bronzes, especially in the eastern and southern states, and remained in use into the Warring States period (see detail of inscription from the Warring States Tomb of Marquis Yĭ of Zēng below left). In the same areas, in the late Spring and Autumn to early Warring States, scripts which embellished basic structures with decorative forms such as birds or worms also appeared. These are known as Bird Script (niǎoshū 鳥書) and Worm Script (chóngshū 蟲書), and collectively as Bird-worm scripts, (niǎochóngshū 鳥蟲書; see Bronze sword of King Gōujiàn to right); however, these were primarily decorative forms for inscriptions on bronzes and other items, and not scripts in daily use.[19] Some bronzes of the period were incised in a rough, casual manner, with graph structures often differing somewhat from typical ones. It is thought that these reflected the popular (vulgar) writing of the time which coexisted with the formal script.[20]

Warring States period

Seals have been found from the Warring States period, mostly cast in bronze,[21] and minted bronze coins from this period are also numerous. These form an additional, valuable resource for the study of Chinese bronze inscriptions. It is also from this period that the first surviving bamboo and silk manuscripts have been uncovered.[22]

In the early Warring States period, typical bronze inscriptions were similar in content and length to those in the late Western Zhou to Spring and Autumn period.[23] One of the most famous sets of bronzes ever discovered dates to the early Warring States: a large set of biānzhōng bells from the tomb of Marquis Yĭ of the state of Zēng, unearthed in 1978. The total length of the inscriptions on this set was almost 2,800 characters.[23]

Bronze biānzhōng bells from the early Warring States Tomb of Marquis Yĭ of Zēng

In the mid to late Warring States period, the average length of inscriptions decreased greatly.[24] Many, especially on weapons, recorded only the date, maker and so on, in contrast with earlier narrative contents. Beginning at this time, such inscriptions were typically engraved onto the already cast bronzes, rather than being written into the wet clay of piece-molds as had been the earlier practice. The engraving was often roughly and hastily executed.[25]

In Warring States period bronze inscriptions, trends from the late Spring and Autumn period continue, such as the use of artistically embellished scripts (e.g., Bird and Insect Scripts) on decorated bronze items. In daily writing, which was not embellished in this manner, the typical script continued evolving in different directions in various regions, and this divergence was accelerated by both a lack of central political control as well as the spread of writing outside of the nobility.[26] In the state of Qin, which was somewhat culturally isolated from the other states, and which was positioned on the old Zhou homeland, the script became more uniform and stylistically symmetrical,[27] rather than changing much structurally. Change in the script was slow, so it remained more similar to the typical late Western Zhou script as found on bronzes of that period and the Shĭ Zhoù Piān (史籀篇) compendium of ca. 800 BCE.[27][28] As a result, it was not until around the middle of the Warring States period that popular (aka common or vulgar) writing gained momentum in Qin, and even then, the vulgar forms remained somewhat similar to traditional forms, changing primarily in terms of becoming more rectilinear. Traditional forms in Qin remained in use as well, so that two forms of writing coexisted. The traditional forms in Qin evolved slowly during the Eastern Zhou, gradually becoming what is now called (small) seal script during that period, without any clear dividing line (it is not the case, as is commonly believed, that small seal script was a sudden invention by Li Si in the Qin dynasty[29]). Meanwhile, the Qin vulgar writing evolved into early clerical (or proto-clerical) in the late Warring States to Qin dynasty period,[30] which would then evolve further into the clerical script used in the Han through the Wei-Jin periods.[f]

Meanwhile, in the eastern states, vulgar forms had become popular sooner; they also differed more radically from and more completely displaced the traditional forms.[26] These eastern scripts, which also varied somewhat by state or region, were later misunderstood by Xu Shen, author of the Han dynasty etymological dictionary Shuowen Jiezi, who thought they predated the Warring States Qin forms, and thus labeled them gǔwén (古文), or "ancient script".

Computer encoding

It has been anticipated that Bronze script will some day be encoded in Unicode. Codepoints U+32000 to U+32FFF (Plane 3, Tertiary Ideographic Plane) have been tentatively allocated.[31]

See also

- Chinese writing

- Chinese calligraphy

- Oracle bone script

- Seal script

- Clerical script

- Houmuwu ding

Notes

^ There are also extremely small numbers of inscriptions from the Zhōuyuán (周原) oracle bones dating to the start of the Zhou dynasty (Qiú 2000, pp.68-9), as well as the Shĭ Zhoù Piān (史籀篇) compendium of ca. 800 BCE, a tiny fraction of which has been preserved as the zhòuwén (籀文) examples in Shuowen Jiezi, and finally, the Stone Drums of Qin of the late Spring and Autumn period.

^ Bronze inscriptions also exist for the periods preceding and following this; but the bulk of earlier (Shang dynasty) writing is in oracle bone script, while later writings are also available on bamboo books, silk books, and stone monuments (stelae) in significant quantities.

^ Qiú 2000, p.68 cites 291 on the Dà Yú Dĭng (大盂鼎) , about 400 on the Xiǎo Yú Dĭng (小盂鼎), 350 on the Sǎn Shì Pán (散氏盤), 498 on the Máo Gōng Dĭng (毛公鼎), and 493 on a large bó bell cast by Shū Gōng (叔弓 (sic)) in the Spring and Autumn period.

^ The main writing medium of the time is believed to have been the writing brush and bamboo or wood books; although they have not survived, the character for such books, 冊 cè, showing their vertical slats bound with a horizontal string, is found on Shang and Zhou bronzes, as is the graph for the writing brush (see Qiú 2000, p.63, and Xǔ Yǎhuì, p.12). Historical references to use by the Shang of such books also exist, e.g., in the Duōshì chapter of the Shàngshū (Qiú pp.62-3)

冊 cè, showing their vertical slats bound with a horizontal string, is found on Shang and Zhou bronzes, as is the graph for the writing brush (see Qiú 2000, p.63, and Xǔ Yǎhuì, p.12). Historical references to use by the Shang of such books also exist, e.g., in the Duōshì chapter of the Shàngshū (Qiú pp.62-3)

^ Qiú 2000, p.69; p.65 footnote 5 also mentions that highly pictographic clan emblems and other identificational forms are still found in the Zhou period, especially the beginning of the W. Zhou.

^ Although popularly associated only with the Han dynasty, clerical actually remained in use alongside cursive, neo-clerical and semi-cursive scripts until after the Wei-Jin period, when the modern standard script became dominant; see Qiu 2000, p.113

References

- Footnotes

^ Qiú 2000 p.60

^ ab Wilkinson (2000): 428.

^ ab Qiú 2000, p.62

^ Xu Yahui, p.12

^ Qiu 2000, p.63

^ Qiu 2000, p.67

^ Qiú 2000, p.60

^ abc Qiú 2000, p.64

^ Qiú 2000 p.62

^ ab Qiú 2000, p.63

^ ab Qiú 2000, p.70

^ Qiú 2000, p.65

^ Qiú 2000, p.67

^ Qiú 2000, pp.69-70

^ Qiú 2000, p.100

^ Qiú 2000, p.77

^ Qiú 2000, p. 71 & 76

^ Qiú 2000, p.80

^ Qiú 2000, pp.71-72

^ Qiu 2000, p.72

^ Qiú 2000, p.80 notes that some were also silver or jade

^ Qiú 2000, p.81

^ ab Qiú 2000, p.79

^ Qiú 2000, p. 79

^ Qiú 2000, p.79-80 & 93

^ ab Qiú 2000, p.78

^ ab Qiú 2000, p.97

^ 陳昭容 Chén Zhāoróng 2003

^ Qiú 2000, p.107

^ Qiú 2000, p.78, 104 & 107

^ The Unicode Consortium, Roadmap to the TIP

- Bibliography

- Chen Zhaorong 陳昭容 (2003) Qinxi wenzi yanjiu: cong hanzi-shi de jiaodu kaocha 秦系文字研究:从漢字史的角度考察 (Research on the Qin Lineage of Writing: An Examination from the Perspective of the History of Chinese Writing). Taipei: Academia Sinica, Institute of History and Philology Monograph. .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 957-671-995-X (Chinese). - Deydier, Christian (1980). Chinese Bronzes. New York: Rizzoli NK7904.D49, SA

Qiu Xigui (2000). Chinese Writing. Translated by Gilbert Mattos and Jerry Norman. Early China Special Monograph Series No. 4. Berkeley: The Society for the Study of Early China and the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley.

ISBN 1-55729-071-7.

Rawson, Jessica (1980). Ancient China: Art and Archaeology. London: British Museum Publications.- Rawson, Jessica (1987). Chinese Bronzes: Art and Ritual. London.

- Rawson, Jessica (1983). The Chinese Bronzes of Yunnan. London and Beijing: Sidgwick and Jackson.

Shaughnessy, Edward L. (1991). Sources of Western Zhou History: Inscribed Bronze Vessels. University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, Oxford.

ISBN 0-520-07028-3.- Wang Hui 王輝 (2006). Shang-Zhou jinwen 商周金文 (Shang and Zhou bronze inscriptions). Beijing: Wenwu Publishing. (Chinese)

Wilkinson, Endymion (2000), Chinese History: A Manual (2nd ed.), Cambridge, Massachusetts, London: Harvard University Asia Center.

External links

Eno, Bob (2012). "Inscriptional records of the Western Zhou" (PDF).