Bloody Island (Mississippi River)

1853 Map of Bloody Island towhead | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Mississippi River, East St. Louis, Illinois |

| Coordinates | 38°38′18″N 90°10′26″W / 38.6384°N 90.1738°W / 38.6384; -90.1738Coordinates: 38°38′18″N 90°10′26″W / 38.6384°N 90.1738°W / 38.6384; -90.1738 |

| Administration | |

United States | |

| Additional information | |

| The neutral ground, between Illinois and Missouri, of many notorious duels in the 19th Century, including the duel between Abraham Lincoln and James Shields. | |

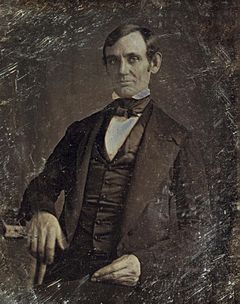

Earliest known photograph of Abraham Lincoln, circa 1845-1847. Lincoln, a Whig, participated in only one known duel: with James Shields, a Democrat, in 1842. After the bloodless "affair of honor", they became the best of friends. | |

| Duration | 1817-1856 |

|---|---|

| Location | Bloody Island Dueling Grounds |

| Participants | Thomas Hart Benton vs. Charles Lucas (fought two duels in 1817) Joshua Barton vs. Thomas C. Rector (1823) Thomas Biddle vs. Spencer Darwin Pettis (1831) Abraham Lincoln vs. James Shields (1842) Benjamin Gratz Brown vs. Thomas C. Reynolds (1856) |

| Casualties | |

Thomas Hart Benton and Charles Lucas, both wounded in first duel Charles Lucas, killed in second duel Joshua Barton, killed Thomas Biddle vs. Spencer Darwin Pettis, both killed Benjamin Gratz Brown, wounded | |

Bloody Island was a sandbar or "towhead" (river island) in the Mississippi River, opposite St. Louis, Missouri, which became densely wooded and a rendezvous for duelists because it was considered "neutral" and not under Missouri or Illinois control.[1]

Contents

1 History

2 Notable duels

3 Sources

4 References

History

After its first appearance above water in 1798, its continuous growth menaced the harbor of St. Louis. In 1837 Capt. Robert E. Lee, of U.S. Army Engineers, devised and established a system of dikes and dams that washed out the western channel and ultimately joined the island to the Illinois shore.

The south end of the island is now under the Poplar Street Bridge at the site of a train yard. Samuel Wiggins bought 800 acres (3.2 km2) around the island in the early 19th century and operated a ferry between East St. Louis and St. Louis (at one point using an 8-horse team on the ferry to provide the propulsion). The Wiggins Ferry Service would develop the train yards which in the 1870s carted train cars across the river one at a time until the Eads Bridge opened in 1879. The train yard is now owned by the Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis.

Notable duels

Thomas Hart Benton and Charles Lucas (twice) in 1817 - Benton and Lucas were both attorneys, and had taken opposing sides in a land dispute. In the midst of the trial, Benton insulted Lucas by calling him an outright liar. A few weeks later, during a local election, Lucas accused Benton of not having a right to vote because he had not paid his property tax. Benton responded to this accusation by calling Lucas a "little puppy" and a character of little significance. When Lucas was informed of Benton's insult, he challenged Benton to a duel. In the initial encounter Lucas was shot in the throat and Benton was grazed in the knee. Although both parties had achieved satisfaction under the dictates of the Code Duello, Benton demanded that they shoot again. Eventually, Benton was talked out of a second round, but when Lucas—having healed from his wound—started to change the story to support his character over Benton's, Benton challenged him to a second duel and summarily killed him.

Joshua Barton and Thomas C. Rector - June 30, 1823 - Barton was the first Missouri Secretary of State, a St. Louis federal district attorney, and brother of Senator David Barton. He had been Lucas' second in Lucas's two duels with Thomas Hart Benton (see above). Senator Barton was critical of reappointing Rector's brother William Rector Surveyor General in regards to the survey of the Louisiana Purchase territory. Barton published the charges in the St. Louis Republican and was challenged by Rector to a duel. Barton was killed and Rector escaped unhurt. President James Madison would not reappoint Rector.[2] Rector would die two years later in a knife fight.

Thomas Biddle and Spencer Darwin Pettis — August 26, 1831 — One of the most famous duels to occur on Bloody Island, it is often cited as an example of the theory that "all politics is local." Pettis, a staunch Jacksonian Democrat, challenged Biddle, brother of banker Nicholas Biddle, because Biddle had publicly humiliated Pettis. Because the Code Duello stated that the particulars of the duel were to be decided by the "challengee," Biddle, who was nearsighted, chose Bloody Island and a distance of five feet. It is argued[by whom?] that Biddle thought such a close distance would convince Pettis not to go through with the duel, but Pettis was undeterred. They fired at five feet, and both were killed.

Abraham Lincoln and James Shields — September 22, 1842 — Lincoln, who was a Whig, had written a letter highly critical of Shields, a Democrat, that was published in the Springfield, Illinois newspaper, the Sangamo Journal. Shields was outraged, enough to challenge Lincoln to a duel. Lincoln chose cavalry sabers, which would give him the edge. Having the strength and height advantage, Lincoln lopped a branch off a tree. The bloodless duel ended, when the friends of the duellists, convinced them to make a truce.[3]

Benjamin Gratz Brown and Thomas C. Reynolds — August 26, 1856 — Brown at the time was editor of the St. Louis Democrat and Reynolds was United States Attorney in St. Louis. Reynolds, who opposed emancipation, challenged Brown, who favored it. Brown was shot in the leg and limped for the rest of his life; Reynolds was not hurt. The duel was called the "Duel of the Governors" because Reynolds would become the state's Confederate governor and Brown would be elected governor after the war.

Sources

Dictionary of American History by James Truslow Adams, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1940- Crack of the Pistol: Dueling in 19th Century Missouri (Missouri State Archives)

- Mark Neels, "The Barbarous Custom of Dueling," in The Lindenwood Confluence (Fall, 2010).

References

^ "History of Bloody Island and its Duels". www.museum.state.il.us. Retrieved 2018-08-19..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Dictionary of Missouri Biography by Lawrence O. Christensen (Editor), William E. Foley (Editor), Gary R. Kremer (Editor), Kenneth H. Winn (Editor) - University of Missouri Press (October 1999)

ISBN 0-8262-1222-0

^ http://www.civilwar.org/education/history/lincoln-hub/abraham-lincolns-duel.html