Numidia

Kingdom of Numidia Inumiden | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 202 BC–40 BC | |||||||||||

Numidian coins under Massinissa | |||||||||||

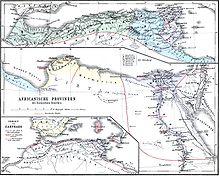

Map of Numidia at its greatest extent | |||||||||||

| Capital | Cirta (today Constantine, Algeria) | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Numidian, Latin, Punic[1] | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

• 202–148 BC | Masinissa | ||||||||||

• 60–46 BC | Juba I of Numidia | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Antiquity | ||||||||||

• Established | 202 BC | ||||||||||

• Annexed by the Roman Republic | 40 BC | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Algeria, Tunisia and Libya | ||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Algeria |

|

Prehistory

|

Antiquity

|

Middle Ages

|

Modern times Ottoman Algeria (16th - 19th centuries)

French Algeria (19th - 20th centuries)

|

Contemporary era 1960s–80s

1990s

2000s to present

|

Related topics

|

Numidia (202 BC – 40 BC, Berber: Inumiden) was an ancient Berber kingdom of the Numidians, located in what is now Algeria and a smaller part of Tunisia and Libya in the Berber world, in North Africa. The polity was originally divided between Massylii in the east and Masaesyli in the west. During the Second Punic War (218–201 BC), Massinissa, king of the Massylii, defeated Syphax of the Masaesyli to unify Numidia into one kingdom. The kingdom began as a sovereign state and later alternated between being a Roman province and a Roman client state. It was bordered by Atlantic ocean to the west, Africa Proconsularis (modern-day Tunisia) to the east, the Mediterranean Sea to the north, and the Sahara Desert to the south. It is considered to be one of the first major states in the history of Algeria and the Berber world.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Independence

1.2 War with Rome

1.3 Divided kingdom

1.4 Roman provinces

2 Major cities

3 Episcopal sees

4 See also

5 References

6 Further reading

7 External links

History

Independence

The Numidian mauseoleum of El-Khroub

The Greek historians referred to these peoples as "Νομάδες" (i.e. Nomads), which by Latin interpretation became "Numidae" (but cf. also the correct use of Nomades).[2] Historian Gabriel Camps, however, disputes this claim, favoring instead an African origin for the term.[3]

The name appears first in Polybius (second century BC) to indicate the peoples and territory west of Carthage including the entire north of Algeria as far as the river Mulucha (Muluya), about 160 kilometres (100 mi) west of Oran.[4]

The Numidians were composed of two great tribal groups: the Massylii in eastern Numidia, and the Masaesyli in the west. During the first part of the Second Punic War, the eastern Massylii, under their king Gala, were allied with Carthage (a 'Punic', i.e. Phoenician, Semitic, mercantile sea empire called after its capital in present Tunisia), while the western Masaesyli, under king Syphax, were allied with Rome. However, in 206 BC, the new king of the eastern Massylii, Masinissa, allied himself with Rome, and Syphax of the Masaesyli switched his allegiance to the Carthaginian side. At the end of the war, the victorious Romans gave all of Numidia to Masinissa of the Massylii.[4] At the time of his death in 148 BC, Masinissa's territory extended from Mauretania to the boundary of the Carthaginian territory, and also southeast as far as Cyrenaica, so that Numidia entirely surrounded Carthage (Appian, Punica, 106) except towards the sea.

After the death of the long-lived Masinissa around 148 BC, he was succeeded by his son Micipsa. When Micipsa died in 118 BC, he was succeeded jointly by his two sons Hiempsal I and Adherbal and Masinissa's illegitimate grandson, Jugurtha, of Ancient Libyan origin, who was very popular among the Numidians. Hiempsal and Jugurtha quarrelled immediately after the death of Micipsa. Jugurtha had Hiempsal killed, which led to open war with Adherbal.[citation needed]

War with Rome

By 112 BC, Jugurtha resumed his war with Adherbal. He incurred the wrath of Rome in the process by killing some Roman businessmen who were aiding Adherbal. After a brief war with Rome, Jugurtha surrendered and received a highly favourable peace treaty, which raised suspicions of bribery once more. The local Roman commander was summoned to Rome to face corruption charges brought by his political rival Gaius Memmius. Jugurtha was also forced to come to Rome to testify against the Roman commander, where he[which?] was completely discredited once his violent and ruthless past became widely known, and after he had been suspected of murdering a Numidian rival.

War broke out between Numidia and the Roman Republic and several legions were dispatched to North Africa under the command of the Consul Quintus Caecilius Metellus Numidicus. The war dragged out into a long and seemingly endless campaign as the Romans tried to defeat Jugurtha decisively. Frustrated at the apparent lack of action, Metellus' lieutenant Gaius Marius returned to Rome to seek election as Consul. Marius was elected, and then returned to Numidia to take control of the war. He sent his Quaestor Lucius Cornelius Sulla to neighbouring Mauretania in order to eliminate their support for Jugurtha. With the help of Bocchus I of Mauretania, Sulla captured Jugurtha and brought the war to a conclusive end. Jugurtha was brought to Rome in chains and was placed in the Tullianum.[citation needed]

Jugurtha was executed by the Romans in 104 BC, after being paraded through the streets in Gaius Marius' Triumph.[citation needed]

Divided kingdom

After the death of Jugurtha, the far west of Numidia was added to the lands of Bocchus I, king of Mauretania.[4] A rump kingdom continued to be governed by native princes.[4] It appears that on the death of King Gauda in 88 BC, the kingdom was divided into a larger eastern kingdom and a smaller western kingdom (roughly the Petite Kabylie). The kings of the east minted coins, while no known coins of the western kings survive. The western kings may have been vassals of the eastern.[5][6]

The civil war between Caesar and Pompey brought an end to independent Numidia in 46 BC.[4] The western kingdom between the Sava (Oued Soummam) and Ampsaga (Oued-el-Kebir) rivers passed to Bocchus II, while the eastern kingdom became a Roman province. The remainder of the western kingdom plus the city of Cirta, which may have belonged to either kingdom, became briefly an autonomous principality under Publius Sittius. Between 44 and 40 BC, the old western kingdom was once again under a Numidian king, Arabio, who killed Sittius and took his place. He involved himself in Rome's civil wars and was himself killed.[6]

Roman provinces

Northern Africa under Roman rule

After the death of Arabio, Numidia became the Roman province of Africa Nova except for a brief period when Augustus restored Juba II (son of Juba I) as a client king (29–27 BC).

Eastern Numidia was annexed in 46 BC to create a new Roman province, Africa Nova. Western Numidia was also annexed after the death of its last king, Arabio, in 40 BC, and the two provinces were united with Tripolitana by Emperor Augustus, to create Africa Proconsularis. In AD 40, the western portion of Africa Proconsularis, including its legionary garrison, was placed under an imperial legatus, and in effect became a separate province of Numidia, though the legatus of Numidia remained nominally subordinate to the proconsul of Africa until AD 203.[7] Under Septimius Severus (193 AD), Numidia was separated from Africa Proconsularis, and governed by an imperial procurator.[4] Under the new organization of the empire by Diocletian, Numidia was divided in two provinces: the north became Numidia Cirtensis, with capital at Cirta, while the south, which included the Aurès Mountains and was threatened by raids, became Numidia Militiana, "Military Numidia", with capital at the legionary base of Lambaesis. Subsequently, however, Emperor Constantine the Great reunited the two provinces in a single one, administered from Cirta, which was now renamed Constantina (modern Constantine) in his honour. Its governor was raised to the rank of consularis in 320, and the province remained one of the seven provinces of the diocese of Africa until the invasion of the Vandals in 428 AD, which began its slow decay,[4] accompanied by desertification. It was restored to Roman rule after the Vandalic War, when it became part of the new praetorian prefecture of Africa.[citation needed]

Major cities

Numidia became highly romanized and was studded with numerous towns.[4] The chief towns of Roman Numidia were: in the north, Cirta or modern Constantine, the capital, with its port Russicada (Modern Skikda); and Hippo Regius (near Bône), well known as the see of St. Augustine. To the south in the interior military roads led to Theveste (Tebessa) and Lambaesis (Lambessa) with extensive Roman remains, connected by military roads with Cirta and Hippo, respectively.[4][8]

Lambaesis was the seat of the Legio III Augusta, and the most important strategic centre.[4] It commanded the passes of the Aurès Mountains (Mons Aurasius), a mountain block that separated Numidia from the Gaetuli Berber tribes of the desert, and which was gradually occupied in its whole extent by the Romans under the Empire. Including these towns, there were altogether twenty that are known to have received at one time or another the title and status of Roman colonies; and in the 5th century, the Notitia Dignitatum enumerates no fewer than 123 sees whose bishops assembled at Carthage in 479.[4]

Episcopal sees

Ancient episcopal sees of Numidia listed in the Annuario Pontificio as titular sees:[9]

- Alba (in the region of Qarentina)

- Ampora

Aquae (Henchir-El-Hammam)- Aquae Novae

Aquae Thibilitanae (Hammam-Meskhoutine)- Arae

Arsacal (Goulia)

Augurus (ruins of Sidi-Tahar and Sidi-Embarec?)

Ausuccura (Ascours?)- Azura

Babra, Numidia (ruins in the territory of Babar)

Badiae (Badès)

Bagai (Ksar-Bagaï)

Baia, Numidia (Henchir Settara? Henchir-El-Hammam?)- Bamaccora

- Barica

- Belesasa

- Betagbara

- Bocconia

- Buffada

- Burca

Caesarea (Youks-les-Bains, Henchir-El-Hammam)

Caesariana (ruins of Kessaria)- Calama

Capsus, Numidia (Aïn-Guigba)- Casae Calanae

Casae (El Madher)

Casae Medianae (Henchir-El-Taouil?)

Casae Nigrae (near Negrine)

Castellum (Henchir-Gastal)- Castellum Titulianum

Castra Galbae (Ksar-Galaba?)

Cataquas (near Annaba)

Cediae (Oum-Kif)

Celerina (Guebeur-Bou-Aoun)- Cemerianus

Centenaria (Henchir-El-Harmel? Henchir-Cheddi?)

Centuria (ruins of Aïn-Hadjar-Allah? Fedj-Deriasse?)

Centuriones (ruins of El-Kentour)

Ceramussa (Gueramoussa?)

Chullu (Collo)

Coeliana (Ain Tine)

Cuicul (Djémila)

Diana (Numidia) (Aïn Zana)- Dusa

- Fata

- Fesseë

- Forma (ruins of Kherbet-Fraim?)

- Fussala

Gadiaufala (Ksar Sbehi)- Garba (ruins of Aïn-Garb)

- Gaudiaba

Gauriana (Henchir-Gouraï?)- Gemellae

Germania (ruins of Ksar-El-Kelb?)- Gibba (Henchir-Dibba)

- Gilba

- Giru Marcelli

- Girus (in the region of Djemila?)

- Girus Tarasii

Guzabeta (ruins at Henchir-Zerdan?)- Hospita

Idassa (has namesakes) (near Merkeb-Talha)

Idicra (Aïn-Aziz-Bin-Tellis)- Iucundiana

- Iziriana

- Irzidzada

Lambaesis (in the territory of Batna)

Lambiridi (Kherbet-Ouled-Arif)

Lamiggiga (Seriana)

Lamphua (Aïn-Foua)

Lamsorti (Henchir-Mâfouna)

Lamzella (Henchir-Resdis)- Leges (in the territory of Mila or Annaba)

- Legia

- Legis Volumni

- Liberalia (oasis of Lioua?)

- Limata (in the territory of Mila)

- Lugura (Aïn-Laoura?)

Macomades (Merkeb-Talha)

Macomades Rusticiana (Canrobert, Oum-El-Bouaghi?)- Madaurus

- Mades

Magarmel (Aïn-Moughmel?)

Mascula (Khenchela)- Mathara

Maximiana (ruins of Mexmeia?)- Mazaca

Merouana (Lamasba)- Mesarfelta

- Meta

- Midila (Mdila?)

- Milevum

Mons (near Mdila)- Moxori

- Mulia (ruins of El-Milia?)

- Municipa

- Musti

Mutugenna (ruins of Aïn-Tebla?)- Naratcata

- Nasai (Aïn Zoul?)

- Nebbi (in the territory of Tobma)

Nicives (N'Gaous)- Nigizubi

Nigrae Maiores (Besseriani)

Nova Barbara (ruins of Beni-Barbar?, Henchir-Barbar?)- Nova Caesaris

- Nova Germania (near Khamissa)

- Nova Petra (ruins of Encedda?)

- Nova Sinna

- Nova Soarsa

- Octava

- Pauzera

- Pudentiana

- Regiana (Henchir-Tacoucht?)

- Respecta

Ressiana (in the territory of Mila)- Rotaria (Henchir-Loulou, Renier?)

Rusicade (Skikda)- Rusticiana

- Seleuciana

- Sigus

- Sila (Bordj-El-Ksar)

- Silli

- Sinitis (near Annaba)

- Sistroniana

Sitifis (Setif)- Suava

- Summa (ruins of Zemma?)

Tabuda (Thouda)- Tacarata (in the territory of Mila or in that of Annaba)

Tarasa (Henchir-Tarsa?)- Teglata

- Thagaste

- Thagora

- Thamugadi

- Theveste

Thiava (near Annaba or Souk-Ahras)- Thibaris

Thibilis (Announa)- Thinisa

- Thubunae

Thubursicum (Khemissa)

Thucca (Henchir-El-Abiodh)- Tiddi

- Tigillava (Mechta-Djillaoua)

Tigisis (Aïn el-Bordj)- Tipasa in Numidia

Tisedi (near Aziz-Ben-Tellis)

Tituli in Numidia (ruins of Aïn-Nemeur? ruins of Aïn-Merdja?)- Tullia (near Annaba)

Turres (in the territory of Annaba)- Turres Ammeniae

- Turres Concordiae

Tubusuptu (Tiklat)- Turris Rotunda

Ubaza (Terrebaza)

Vaga (modern day Béja)- Vadesi

Vagada (ruins of El-Aria?)- Vageata

- Vagrauta

- Vatarba

Vegesela in Numidia (ruins of Ksar-Bou-Saïd? of Ksar-El-Kelb? Henchir-El-Abiodh?)

Velefi (ruins of Fedj-Es-Soyoud?)

Verrona (Henchir-El-Hatba)

Vescera (Biskra)- Vicus Caesaris

Vicus Pacati (Aïn-Mechara?)- Villa regis (near Tobna)

- Zaba (ruins of Tolga in the territory of Zab?)

- Zaraï

Zattara (Bouchegouf District)- Zerta (near Merkeb-Talha)

See also

- List of Kings of Numidia

- Numidians

- Numidian cavalry

- Roman Libya

- Africa (Roman province)

- Shawiya language

References

^ Jongeling. Karel & Kerr, Robert M. (2005). Late Punic epigraphy: an introduction to the study of Neo-Punic and Latino-Punic inscriptions. Mohr Siebeck. p. 4. ISBN 3-16-148728-1..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Numida and Nomas

^ Camps, Gabriel. "Les Numides et la civilisation punique". Antiquités africaines (in French). 14 (1): 43–53. doi:10.3406/antaf.1979.1016.

^ abcdefghijk Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Numidia". Encyclopædia Britannica. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 868–869.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Numidia". Encyclopædia Britannica. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 868–869.

^ Duane W. Roller (2003), The World of Juba II and Kleopatra Selene: Royal Scholarship on Rome's African Frontier, New York: Routledge, p. 25.

^ ab Gabriel Camps (1989) [published online 2012], "Arabion", Encyclopédie berbère, 6: Antilopes–Arzuges, Aix-en-Provence: Edisud, pp. 831–34, retrieved 13 February 2017.

^ J. D. Fage; Roland Anthony Oliver (1975). The Cambridge History of Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-521-21592-3.

^ Detailed map of Roman Numidia

^ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2013,

ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), "Sedi titolari", pp. 819–1013

Further reading

(in French) Daho, Keltoum Kitouni; Filah, Mohamed El Mostéfa (2003). L'Algérie au temps des royaumes numides ["Algeria at the time of the Numidian kingdoms"]. Somogy Editions d'Art. ISBN 2850566527.

(in German) Horn, Heinz Günter; Rüger, Christoph B. (1979). Die Numider. Reiter und Könige nördlich der Sahara ["The Numidians. Horsemen and kings north of the Sahara"]. Rheinland. ISBN 3792704986.

Kuttner, Ann (2013). "Representing Hellenistic Numidia, in Africa and at Rome". In Jonathan R. W. Prag, Josephine Crawley Quinn. The Hellenistic West. Rethinking the Ancient Mediterranean. Cambridge University. pp. 216–272. ISBN 1107032423.

Quinn, Josephine Crawley (2013). "Monumental power: 'Numidian Royal Architecture' in context". In Jonathan R. W. Prag, Josephine Crawley Quinn. The Hellenistic West. Rethinking the Ancient Mediterranean (PDF). Cambridge University. pp. 179–215. ISBN 1107032423.

External links

- Numidia.startkabel.nl (Links in Dutch and English)