Marcus Aurelius

| Marcus Aurelius | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Augustus | |||||

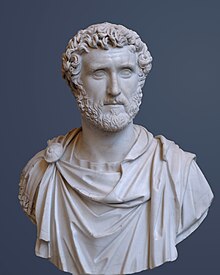

Bust of Marcus Aurelius in the Archaeological Museum of Istanbul, Turkey | |||||

| Emperor of the Roman Empire | |||||

| Reign | 8 March 161 – 17 March 180 | ||||

| Predecessor | Antoninus Pius | ||||

| Successor | Commodus | ||||

| Co-emperor | Lucius Verus (161–169) Commodus (177–180) | ||||

| Born | Marcus Annius Verus 26 April 121 Rome | ||||

| Died | 17 March 180(180-03-17) (aged 58) Vindobona or Sirmium | ||||

| Burial | Hadrian's Mausoleum | ||||

| Spouse | Faustina the Younger | ||||

| Issue Detail | 14, incl. Commodus, Marcus Annius Verus Caesar, Antoninus and Lucilla | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Nerva-Antonine | ||||

| Father |

| ||||

| Mother | Domitia Lucilla | ||||

|

| Part of a series on |

| Marcus Aurelius |

|---|

Early life (121–161 AD) Reign (161–180 AD) |

Marcus Aurelius (/ɔːˈriːliəs/; Latin: Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180 AD), called the Philosopher, was Roman emperor from 161 to 180. He ruled the Roman Empire with his adoptive brother, Lucius Verus, until Lucius' death in 169. He was the last of the rulers traditionally known as the Five Good Emperors. He is also seen as the last emperor of the Pax Romana, an age of relative peace and stability for the Empire.

Marcus was born into a Roman patrician family; his father, Marcus Annius Verus (III), was the grandson of the Roman senator Marcus Annius Verus (I), and his mother, Domitia Lucilla Minor, was a wealthy heiress like her own mother, Domitia Lucilla Maior. After the death of Marcus' father while praetor in 124, Marcus' paternal grandfather Marcus Annius Verus (II) raised him. As children from other aristocratic families often were, Marcus was educated at home, and he would thank Lucius Catilius Severus–Domitia Lucilla Maior's stepfather who helped Verus (II) raise the young Marcus–for his education. His tutors included the artist Diognetus, who may have sparked his interest in philosophy, and Tuticius Proclus. After the death in 138 of Lucius Aelius, who was the adopted son and heir of Marcus' relative Emperor Hadrian and to whose daughter Ceionia Fabia Marcus was betrothed at the time, Hadrian adopted Antoninus Pius, the husband of Marcus' aunt Faustina the Elder, as his new heir. Antoninus in turn adopted Marcus and Lucius Verus, Aelius' son, and became emperor after the death of Hadrian later that year.

While imperial heir, Marcus was taught Greek by tutors who included Herodes Atticus and Latin by Marcus Cornelius Fronto; he kept in close correspondence with the latter, even as emperor. Despite the warnings of Atticus about Stoicism, Marcus was introduced to the philosophy by Quintus Junius Rusticus and perhaps by philosophers such as Apollonius of Chalcedon. In his early years as heir apparent, Marcus was made a quaestor and the symbolic head of the Roman equites (also known as the knight class). He was consul with Antoninus in 140 and 145–the year he married Antoninus' daughter Faustina the Younger. Marcus took on more responsibilities of state as Antoninus grew older; he was consul with his adoptive brother Lucius in 161 when Antoninus died and they succeeded to the imperial throne.

During Marcus' reign, the Roman fought the Roman-Parthian War (161–166) which resulted in the defeat of a revitalized Parthian Empire in the East; Marcus' general Avidius Cassius sacked the Parthian capital Ctesiphon in 164. In the same year, Lucius married Marcus' daughter Lucilla. In central Europe, Marcus fought the Marcomanni, Quadi, and Sarmatians with success during the Marcomannic Wars (166–180), although the threat of the Germanic peoples began to represent a troubling reality for the Empire. Marcus modified the silver purity of the denarius, and Roman coins found in Han China dating from the reign of Tiberius to that of Aurelian, including coins minted during the reigns of Marcus and Antoninus, are evidence that the Roman Empire traded with China during that time. The Column and Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius still stand in Rome, where they were erected in celebration of his military victories. Persecution of Christians is believed to have increased during his reign. The Antonine Plague, a pandemic that broke out in 165, devastated the population of the Roman Empire; it may have caused the death of Marcus' co-ruler Lucius in 169. Marcus never adopted a successor unlike a number of his predecessors, because he and his wife Faustina had at least thirteen biological children; Marcus named two of their sons, Commodus and Annius, as his successors in 166. Upon his death in 180, Marcus was succeeded by Commodus, by then his only surviving son (four of Marcus' daughters also survived their father), who had been his co-ruler since 177. Marcus' personal philosophical writings, which he wrote in the last ten years of his life and which later came to be called Meditations, are a significant source of the modern understanding of ancient Stoic philosophy. His writings have been praised by fellow writers, philosophers, and monarchs–as well as by poets and politicians–centuries after Marcus' death.

Contents

1 Sources

2 Early life and career

2.1 Name

2.2 Family origins

2.3 Childhood

2.4 Succession to Hadrian

2.5 Heir to Antoninus Pius (138–145)

2.6 Fronto and further education

2.7 Births and deaths

2.8 Antoninus Pius' last years

3 Emperor

3.1 Accession of Marcus Aurelius and Verus (161)

3.2 Early rule

3.3 War with Parthia (161–166)

3.4 War with Germanic tribes (166–180)

3.5 Legal and administrative work

3.6 Plague

3.7 Death and succession (180)

4 Legacy and reputation

5 Attitude towards Christians

6 Marriage and children

7 Writings

8 Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius

9 Column of Marcus Aurelius

10 Notes

11 Citations

12 References

12.1 Ancient sources

12.2 Modern sources

13 External links

Sources

The major sources depicting the life and rule of Marcus are patchy and frequently unreliable. The most important group of sources, the biographies contained in the Historia Augusta, claim to be written by a group of authors at the turn of the 4th century AD, but were in fact written by a single author (referred to here as "the biographer") from about 395 AD. The later biographies and the biographies of subordinate emperors and usurpers are unreliable, but the earlier biographies, derived primarily from now-lost earlier sources (Marius Maximus or Ignotus), are much more accurate.[1] For Marcus' life and rule, the biographies of Hadrian, Antoninus, Marcus, and Lucius are largely reliable, but those of Aelius Verus and Avidius Cassius are not.[2]

A body of correspondence between Marcus' tutor Fronto and various Antonine officials survives in a series of patchy manuscripts, covering the period from c. 138 to 166.[3] Marcus' own Meditations offer a window on his inner life, but are largely undateable, and make few specific references to worldly affairs.[4] The main narrative source for the period is Cassius Dio, a Greek senator from Bithynian Nicaea who wrote a history of Rome from its founding to 229 in eighty books. Dio is vital for the military history of the period, but his senatorial prejudices and strong opposition to imperial expansion obscure his perspective.[5]

Some other literary sources provide specific details: the writings of the physician Galen on the habits of the Antonine elite, the orations of Aelius Aristides on the temper of the times, and the constitutions preserved in the Digest and Codex Justinianus on Marcus' legal work.[6]Inscriptions and coin finds supplement the literary sources.[7]

Denarius of Antoninus Pius (AD 139), with a portrait of his adoptive son Marcus Aurelius on the reverse.[8]

Marcus Aurelius depicted with his wife Faustina the Younger

Marcus Aurelius depicted with his adoptive brother and co-ruler Lucius Verus

Medallion of Marcus Aurelius

Medallion of Marcus Aurelius

Early life and career

Name

Bronze medallion of Marcus Aurelius (AD 168). The reverse depicts Jupiter, flanked by Marcus and Lucius Verus.[9]

Marcus was born in Rome on 26 April 121. His name at birth was supposedly Marcus Annius Verus,[10] but some sources assign this name to him upon his father's death and unofficial adoption by his grandfather, upon his coming of age,[11][12][13] or at the time of his marriage.[14] He may have been known as Marcus Annius Catilius Severus,[15] at birth or at some point in his youth,[11][13] or Marcus Catilius Severus Annius Verus. Upon his adoption by Antoninus as heir to the throne, he was known as Marcus Aelius Aurelius Verus Caesar and, upon his ascension, he was Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus until his death;[16]Epiphanius of Salamis, in his chronology of the Roman emperors On Weights and Measures, calls him Marcus Aurelius Verus.[17]

Family origins

A bust of Marcus Aurelius as a young boy (Capitoline Museum). Anthony Birley, his modern biographer, writes of the bust: "This is certainly a grave young man."[18]

Marcus' family originated in Ucubi, a small town southeast of Córdoba in Iberian Baetica. The family rose to prominence in the late 1st century AD. Marcus' great-grandfather Marcus Annius Verus (I) was a senator and (according to the Historia Augusta) ex-praetor; in 73–74, his grandfather, Marcus Annius Verus (II), was made a patrician.[19][notes 1] Verus' elder son—Marcus' father—Marcus Annius Verus (III) married Domitia Lucilla.[22]

Lucilla was the daughter of the patrician P. Calvisius Tullus Ruso. Her mother, also Domitia Lucilla, had inherited a great fortune (described at length in one of Pliny's letters) from her maternal grandfather and her paternal grandfather by adoption.[23] The younger Lucilla would acquire much of her mother's wealth, including a large brickworks on the outskirts of Rome—a profitable enterprise in an era when the city was experiencing a construction boom.[24]

Childhood

Statue of young Marcus Aurelius from a private collection housed in the San Antonio Museum of Art

Marcus' sister, Annia Cornificia Faustina, was probably born in 122 or 123.[25] His father probably died in 124, during his praetorship, when Marcus was three years old.[26][notes 2] Though he can hardly have known his father, Marcus wrote in his Meditations that he had learned "modesty and manliness" from his memories of his father and from the man's posthumous reputation.[28] His mother Lucilla did not remarry.[26]

Lucilla, following prevailing aristocratic customs, probably did not spend much time with her son. Instead, Marcus was in the care of "nurses".[29] Even so, Marcus credits his mother with teaching him "religious piety, simplicity in diet", and how to avoid "the ways of the rich".[30] In his letters, he makes frequent and affectionate reference to her; he was grateful that, "although she was fated to die young, yet she spent her last years with me".[31]

After his father's death, Marcus was raised by his paternal grandfather Marcus Annius Verus, who had always retained the legal authority of patria potestas over his son and grandson. Technically this was not an adoption, the creation of a new and different patria potestas. Lucius Catilius Severus, described as Marcus' maternal great-grandfather, also participated in his upbringing; he was probably the elder Domitia Lucilla's stepfather.[13] Marcus was raised in his parents' home on the Caelian Hill, a district he would affectionately refer to as "my Caelian".[32]

It was an upscale area, with few public buildings but many aristocratic villas. Marcus' grandfather owned a palace beside the Lateran, where he would spend much of his childhood.[33] Marcus Aurelius thanks his grandfather for teaching him "good character and avoidance of bad temper".[34] He was less fond of the mistress his grandfather took and lived with after the death of his wife, Rupilia Faustina.[35] Marcus Aurelius was grateful that he did not have to live with her longer than he did.[36]

Marcus was educated at home, in line with contemporary aristocratic trends;[37] he thanks Catilius Severus for encouraging him to avoid public schools.[38] One of his teachers, Diognetus, a painting master, proved particularly influential; he seems to have introduced Marcus Aurelius to the philosophic way of life.[39] In April 132, at the behest of Diognetus, Marcus took up the dress and habits of the philosopher: he studied while wearing a rough Greek cloak, and would sleep on the ground until his mother convinced him to sleep on a bed.[40]

A new set of tutors—Alexander of Cotiaeum, Trosius Aper, and Tuticius Proculus[notes 3]—took over Marcus' education in about 132 or 133.[42] Little is known of the latter two (both teachers of Latin), but Alexander was a major littérateur, the leading Homeric scholar of his day.[43] Marcus thanks Alexander for his training in literary styling.[44] Alexander's influence—an emphasis on matter over style and careful wording, with the occasional Homeric quotation—has been detected in Marcus Aurelius' Meditations.[45]

Succession to Hadrian

@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinner{width:100%!important;max-width:none!important}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center}}

In late 136, Hadrian almost died from a hemorrhage. Convalescent in his villa at Tivoli, he selected Lucius Ceionius Commodus, Marcus' intended father-in-law, as his successor and adopted son[47]invitis omnibus, "against the wishes of everyone".[48] While his motives are not certain, it would appear that his goal was to eventually place the then-too-young Marcus on the throne.[49] As part of his adoption, Commodus took the name Lucius Aelius Caesar. His health was so poor that, during a ceremony to mark his becoming heir to the throne, he was too weak to lift a large shield on his own.[50] After a brief stationing on the Danube frontier, Aelius returned to Rome to make an address to the senate on the first day of 138. The night before the speech, however, he grew ill, and died of a hemorrhage later in the day.[51][notes 4]

On 24 January 138, Hadrian selected Aurelius Antoninus, the husband of Marcus' aunt Faustina the Elder, as his new successor.[53] As part of Hadrian's terms, Antoninus in turn adopted Marcus and Lucius Verus, the son of Lucius Aelius.[54] Marcus became M. Aelius Aurelius Verus, and Lucius became L. Aelius Aurelius Commodus. At Hadrian's request, Antoninus' daughter Faustina was betrothed to Lucius.[55] Marcus reportedly greeted the news that Hadrian had become his adoptive grandfather with sadness, instead of joy. Only with reluctance did he move from his mother's house on the Caelian to Hadrian's private home.[56]

At some time in 138, Hadrian requested in the senate that Marcus be exempt from the law barring him from becoming quaestor before his twenty-fourth birthday. The senate complied, and Marcus served under Antoninus, the consul for 139.[57] Marcus' adoption diverted him from the typical career path of his class. If not for his adoption, he probably would have become triumvir monetalis, a highly regarded post involving token administration of the state mint; after that, he could have served as tribune with a legion, becoming the legion's nominal second-in-command. Marcus probably would have opted for travel and further education instead. As it was, Marcus was set apart from his fellow citizens. Nonetheless, his biographer attests that his character remained unaffected: "He still showed the same respect to his relations as he had when he was an ordinary citizen, and he was as thrifty and careful of his possessions as he had been when he lived in a private household."[58]

Baiae, seaside resort and site of Hadrian's last days. Marcus Aurelius would holiday in the town with the imperial family in the summer of 143.[59] (J.M.W. Turner, The Bay of Baiae, with Apollo and Sybil, 1823)

After a series of suicide attempts, all thwarted by Antoninus, Hadrian left for Baiae, a seaside resort on the Campanian coast. His condition did not improve, and he abandoned the diet prescribed by his doctors, indulging himself in food and drink. He sent for Antoninus, who was at his side when he died on 10 July 138.[60] His remains were buried quietly at Puteoli.[61] The succession to Antoninus was peaceful and stable: Antoninus kept Hadrian's nominees in office and appeased the senate, respecting its privileges and commuting the death sentences of men charged in Hadrian's last days.[62] For his dutiful behavior, Antoninus was asked to accept the name "Pius".[63]

Heir to Antoninus Pius (138–145)

Sestertius of Antoninus Pius (AD 140-144). It celebrates the betrothal of Marcus Aurelus and Faustina the Younger in 139, pictured below Pius, who is holding a statuette of Concordia and clasping hands with Faustina the Elder.[64]

Immediately after Hadrian's death, Antoninus approached Marcus and requested that his marriage arrangements be amended: Marcus' betrothal to Ceionia Fabia would be annulled, and he would be betrothed to Faustina, Antoninus' daughter, instead. Faustina's betrothal to Ceionia's brother Lucius Commodus would also have to be annulled. Marcus Aurelius consented to Antoninus' proposal.[65]

Antoninus bolstered Marcus' dignity: Marcus was made consul for 140, with Antoninus as his colleague, and was appointed as a seviri, one of the knights' six commanders, at the order's annual parade on 15 July 139. As the heir apparent, Marcus became princeps iuventutis, head of the equestrian order. He now took the name Caesar: Marcus Aelius Aurelius Verus Caesar.[66] Marcus would later caution himself against taking the name too seriously: "See that you do not turn into a Caesar; do not be dipped into the purple dye—for that can happen".[67] At the senate's request, Marcus joined all the priestly colleges (pontifices, augures, quindecimviri sacris faciundis, septemviri epulonum, etc.);[68] direct evidence for membership, however, is available only for the Arval Brethren.[69]

Antoninus demanded that Marcus take up residence in the House of Tiberius, the imperial palace on the Palatine. Antoninus also made him take up the habits of his new station, the aulicum fastigium or "pomp of the court", against Marcus' objections.[68] Marcus would struggle to reconcile the life of the court with his philosophic yearnings. He told himself it was an attainable goal—"Where life is possible, then it is possible to live the right life; life is possible in a palace, so it is possible to live the right life in a palace"[70]—but he found it difficult nonetheless. He would criticize himself in the Meditations for "abusing court life" in front of company.[71]

As quaestor, Marcus would have had little real administrative work to do. He would read imperial letters to the senate when Antoninus was absent, and would do secretarial work for the senators. His duties as consul were more significant: one of two senior representatives of the senate, he would preside over meetings and take a major role in the body's administrative functions.[72] He felt drowned in paperwork, and complained to his tutor, Marcus Cornelius Fronto: "I am so out of breath from dictating nearly thirty letters".[73] He was being "fitted for ruling the state", in the words of his biographer.[74] He was required to make a speech to the assembled senators as well, making oratorical training essential for the job.[75]

On 1 January 145, Marcus was made consul a second time. He might have been unwell at this time: a letter from Fronto that might have been sent at this time urges Marcus to have plenty of sleep "so that you may come into the Senate with a good colour and read your speech with a strong voice".[76] Marcus had complained of an illness in an earlier letter: "As far as my strength is concerned, I am beginning to get it back; and there is no trace of the pain in my chest. But that ulcer [...][notes 5] I am having treatment and taking care not to do anything that interferes with it."[77] Marcus Aurelius was never particularly healthy or strong. The Roman historian Cassius Dio, writing of his later years, praised him for behaving dutifully in spite of his various illnesses.[78]

In April 145 AD, Marcus married Faustina, as had been planned since 138 AD. Since Marcus was, by adoption, Antoninus' son, under Roman law he was marrying his sister; Antoninus would have had to formally release one or the other from his paternal authority (his patria potestas) for the ceremony to take place.[79] Little is specifically known of the ceremony, but it is said to have been "noteworthy".[80] Coins were issued with the heads of the couple, and Antoninus, as Pontifex Maximus, would have officiated. Marcus makes no apparent reference to the marriage in his surviving letters, and only sparing references to Faustina.[81]

Fronto and further education

After taking the toga virilis in 136, Marcus probably began his training in oratory.[82] He had three tutors in Greek, Aninus Macer, Caninius Celer, and Herodes Atticus, and one in Latin, Fronto. The latter two were the most esteemed orators of the day,[83] but probably did not become his tutors until his adoption by Antoninus in 138. The preponderance of Greek tutors indicates the importance of the Greek language to the aristocracy of Rome.[84] This was the age of the Second Sophistic, a renaissance in Greek letters. Although educated in Rome, in his Meditations, Marcus would write his inmost thoughts in Greek.[85]

A bust of Herodes Atticus, from his villa at Kephissia (National Archaeological Museum of Athens)

Atticus was controversial: an enormously rich Athenian (probably the richest man in the eastern half of the empire), he was quick to anger, and resented by his fellow Athenians for his patronizing manner.[86] Atticus was an inveterate opponent of Stoicism and philosophic pretensions.[87] He thought the Stoics' desire for a "lack of feeling" foolish: they would live a "sluggish, enervated life", he said.[88] Marcus would become a Stoic. He would not mention Herodes at all in his Meditations, in spite of the fact that they would come into contact many times over the following decades.[89]

Fronto was highly esteemed: in the self-consciously antiquarian world of Latin letters,[90] he was thought of as second only to Cicero, perhaps even an alternative to him.[91][notes 6] He did not care much for Atticus, though Marcus was eventually to put the pair on speaking terms. Fronto exercised a complete mastery of Latin, capable of tracing expressions through the literature, producing obscure synonyms, and challenging minor improprieties in word choice.[91]

A significant amount of the correspondence between Fronto and Marcus has survived.[95] The pair were very close. "Farewell my Fronto, wherever you are, my most sweet love and delight. How is it between you and me? I love you and you are not here."[96] Marcus Aurelius spent time with Fronto's wife and daughter, both named Cratia, and they enjoyed light conversation.[97]

He wrote Fronto a letter on his birthday, claiming to love him as he loved himself, and calling on the gods to ensure that every word he learned of literature, he would learn "from the lips of Fronto".[98] His prayers for Fronto's health were more than conventional, because Fronto was frequently ill; at times, he seems to be an almost constant invalid, always suffering[99]—about one-quarter of the surviving letters deal with the man's sicknesses.[100] Marcus asks that Fronto's pain be inflicted on himself, "of my own accord with every kind of discomfort".[101]

Fronto never became Marcus' full-time teacher, and continued his career as an advocate. One notorious case brought him into conflict with Atticus.[102] Marcus pleaded with Fronto, first with "advice", then as a "favour", not to attack Atticus; he had already asked Atticus to refrain from making the first blows.[103] Fronto replied that he was surprised to discover Marcus counted Atticus as a friend (perhaps Atticus was not yet Marcus' tutor), and allowed that Marcus might be correct,[104] but nonetheless affirmed his intent to win the case by any means necessary: "...the charges are frightful and must be spoken of as frightful. Those in particular which refer to the beating and robbing I will describe in such a way that they savour of gall and bile. If I happen to call him an uneducated little Greek it will not mean war to the death."[105] The outcome of the trial is unknown.[106]

By the age of twenty-five (between April 146 and April 147), Marcus had grown disaffected with his studies in jurisprudence, and showed some signs of general malaise. His master, he writes to Fronto, was an unpleasant blowhard, and had made "a hit at" him: "It is easy to sit yawning next to a judge, he says, but to be a judge is noble work."[107] Marcus had grown tired of his exercises, of taking positions in imaginary debates. When he criticized the insincerity of conventional language, Fronto took to defend it.[108] In any case, Marcus' formal education was now over. He had kept his teachers on good terms, following them devotedly. It "affected his health adversely", his biographer writes, to have devoted so much effort to his studies. It was the only thing the biographer could find fault with in Marcus' entire boyhood.[109]

Fronto had warned Marcus against the study of philosophy early on: "It is better never to have touched the teaching of philosophy...than to have tasted it superficially, with the edge of the lips, as the saying is".[110] He disdained philosophy and philosophers, and looked down on Marcus' sessions with Apollonius of Chalcedon and others in this circle.[95] Fronto put an uncharitable interpretation of Marcus' "conversion to philosophy": "In the fashion of the young, tired of boring work", Marcus had turned to philosophy to escape the constant exercises of oratorical training.[111] Marcus kept in close touch with Fronto, but would ignore Fronto's scruples.[112]

Apollonius may have introduced Marcus to Stoic philosophy, but Quintus Junius Rusticus would have the strongest influence on the boy.[113][notes 7] He was the man Fronto recognized as having "wooed Marcus away" from oratory.[115] He was older than Fronto and twenty years older than Marcus. As the grandson of Arulenus Rusticus, one of the martyrs to the tyranny of Domitian (r. 81–96), he was heir to the tradition of "Stoic Opposition" to the "bad emperors" of the 1st century;[116] the true successor of Seneca (as opposed to Fronto, the false one).[117] Marcus thanks Rusticus for teaching him "not to be led astray into enthusiasm for rhetoric, for writing on speculative themes, for discoursing on moralizing texts.... To avoid oratory, poetry, and 'fine writing.'"[118]

Births and deaths

On November 30, 147, Faustina gave birth to a girl named Domitia Faustina. She was the first of at least thirteen children (including two sets of twins) that Faustina would bear over the next twenty-three years. The next day, 1 December, Antoninus gave Marcus the tribunician power and the imperium—authority over the armies and provinces of the emperor. As tribune, he had the right to bring one measure before the senate after the four Antoninus could introduce. His tribunican powers would be renewed with Antoninus' on 10 December 147.[119]

The Mausoleum of Hadrian, where the children of Marcus and Faustina were buried

The first mention of Domitia in Marcus' letters reveals her as a sickly infant. "Caesar to Fronto. If the gods are willing we seem to have a hope of recovery. The diarrhea has stopped, the little attacks of fever have been driven away. But the emaciation is still extreme and there is still quite a bit of coughing." He and Faustina, Marcus wrote, had been "pretty occupied" with the girl's care.[120] Domitia would die in 151.[121]

In 149, Faustina gave birth again, to twin sons. Contemporary coinage commemorates the event, with crossed cornucopiae beneath portrait busts of the two small boys, and the legend temporum felicitas, "the happiness of the times". They did not survive long. Before the end of the year, another family coin was issued: it shows only a tiny girl, Domitia Faustina, and one boy baby. Then another: the girl alone. The infants were buried in the Mausoleum of Hadrian, where their epitaphs survive. They were called Titus Aurelius Antoninus and Tiberius Aelius Aurelius.[122]

Marcus steadied himself: "One man prays: 'How I may not lose my little child', but you must pray: 'How I may not be afraid to lose him'."[123] He quoted from the Iliad what he called the "briefest and most familiar saying...enough to dispel sorrow and fear":

leaves,

the wind scatters some on the face of the ground;

like unto them are the children of men.

– Iliad vi.146[124]

Another daughter was born on 7 March 150, Annia Aurelia Galeria Lucilla. At some time between 155 and 161, probably soon after 155, Marcus' mother Domitia Lucilla died.[125] Faustina probably had another daughter in 151, but the child, Annia Galeria Aurelia Faustina, might not have been born until 153.[126] Another son, Tiberius Aelius Antoninus, was born in 152. A coin issue celebrates fecunditati Augustae, "the Augusta's fertility", depicting two girls and an infant. The boy did not survive long; on coins from 156, only the two girls were depicted. He might have died in 152, the same year as Marcus' sister Cornificia.[127]

By 28 March 158, when Marcus replied, another of his children was dead. Marcus Aurelius thanked the temple synod, "even though this turned out otherwise". The child's name is unknown.[128] In 159 and 160, Faustina gave birth to daughters: Fadilla and Cornificia, named respectively after Faustina's and Marcus' dead sisters.[129]

Antoninus Pius' last years

Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius' adoptive father and predecessor as emperor (Glyptothek)

Lucius started his political career as a quaestor in 153. He was consul in 154,[130] and was consul again with Marcus in 161.[131] Lucius had no other titles, except that of "son of Augustus". Lucius had a markedly different personality from Marcus: he enjoyed sports of all kinds, but especially hunting and wrestling; he took obvious pleasure in the circus games and gladiatorial fights.[132][notes 8] He did not marry until 164.[136]

In 156, Antoninus turned 70. He found it difficult to keep himself upright without stays. He started nibbling on dry bread to give him the strength to stay awake through his morning receptions. As Antoninus aged, Marcus would take on more administrative duties, more still when he became the praetorian prefect (an office that was as much secretarial as military) as Gavius Maximus died in 156 or 157.[137] In 160, Marcus and Lucius were designated joint consuls for the following year. Antoninus may have already been ill.[129]

Two days before his death, the biographer reports, Antoninus was at his ancestral estate at Lorium, in Etruria,[138] about 19 kilometres (12 mi) from Rome.[139] He ate Alpine cheese at dinner quite greedily. In the night he vomited; he had a fever the next day. The day after that, 7 March 161,[140] he summoned the imperial council, and passed the state and his daughter to Marcus. The emperor gave the keynote to his life in the last word that he uttered when the tribune of the night-watch came to ask the password—"aequanimitas" (equanimity).[141] He then turned over, as if going to sleep, and died.[142] His death closed out the longest reign since Augustus, surpassing Tiberius by a couple of months.[143]

Emperor

Accession of Marcus Aurelius and Verus (161)

Lucius Verus, Marcus Aurelius' co-emperor from 161 to Lucius' death in 169 (Metropolitan Museum of Art lent by the Louvre)

After Antoninus died in 161, Marcus was effectively sole ruler of the Empire. The formalities of the position would follow. The senate would soon grant him the name Augustus and the title imperator, and he would soon be formally elected as Pontifex Maximus, chief priest of the official cults. Marcus made some show of resistance: the biographer writes that he was "compelled" to take imperial power.[144] This may have been a genuine horror imperii, "fear of imperial power". Marcus Aurelius, with his preference for the philosophic life, found the imperial office unappealing. His training as a Stoic, however, had made the choice clear that it was his duty.[145]

Although Marcus showed no personal affection for Hadrian (significantly, he does not thank him in the first book of his Meditations), he presumably believed it his duty to enact the man's succession plans.[146] Thus, although the senate planned to confirm Marcus Aurelius alone, he refused to take office unless Lucius received equal powers.[147] The senate accepted, granting Lucius the imperium, the tribunician power, and the name Augustus.[148] Marcus became, in official titulature, Imperator Caesar Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus; Lucius, forgoing his name Commodus and taking Marcus' family name Verus, became Imperator Caesar Lucius Aurelius Verus Augustus.[149][notes 9] It was the first time that Rome was ruled by two emperors.[152][notes 10]

In spite of their nominal equality, Marcus held more auctoritas, or "authority", than Lucius. He had been consul once more than Lucius, he had shared in Antoninus' administration, and he alone was Pontifex Maximus. It would have been clear to the public which emperor was the more senior.[152] As the biographer wrote, "Verus obeyed Marcus...as a lieutenant obeys a proconsul or a governor obeys the emperor."[153]

Busts of the co-emperors Marcus Aurelius (left) and Lucius Verus (right), British Museum

Immediately after their senate confirmation, the emperors proceeded to the Castra Praetoria, the camp of the Praetorian Guard. Lucius addressed the assembled troops, which then acclaimed the pair as imperatores. Then, like every new emperor since Claudius, Lucius promised the troops a special donative.[154] This donative, however, was twice the size of those past: 20,000 sesterces (5,000 denarii) per capita, with more to officers. In return for this bounty, equivalent to several years' pay, the troops swore an oath to protect the emperors.[155] The ceremony was perhaps not entirely necessary, given that Marcus' accession had been peaceful and unopposed, but it was good insurance against later military troubles.[156]

Upon his accession he also devalued the Roman currency. He decreased the silver purity of the denarius from 83.5% to 79%—the silver weight dropping from 2.68 grams to 2.57 grams.[157]

Antoninus' funeral ceremonies were, in the words of the biographer, "elaborate".[158] If his funeral followed those of his predecessors, his body would have been incinerated on a pyre at the Campus Martius, and his spirit would have been seen as ascending to the gods' home in the heavens. Marcus and Lucius nominated their father for deification. In contrast to their behavior during Antoninus' campaign to deify Hadrian, the senate did not oppose the emperors' wishes. A flamen, or cultic priest, was appointed to minister the cult of the deified Antoninus, now Divus Antoninus. Antoninus' remains were laid to rest in Hadrian's mausoleum, beside the remains of Marcus' children and of Hadrian himself.[159] The temple he had dedicated to his wife, Diva Faustina, became the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina. It survives as the church of San Lorenzo in Miranda.[156]

In accordance with his will, Antoninus' fortune passed on to Faustina.[160] (Marcus had little need of his wife's fortune. Indeed, at his accession, Marcus transferred part of his mother's estate to his nephew, Ummius Quadratus.[161]) Faustina was three months pregnant at her husband's accession. During the pregnancy she dreamed of giving birth to two serpents, one fiercer than the other.[162] On 31 August she gave birth at Lanuvium to twins: T. Aurelius Fulvus Antoninus and Lucius Aurelius Commodus.[163][notes 11] Aside from the fact that the twins shared Caligula's birthday, the omens were favorable, and the astrologers drew positive horoscopes for the children.[165] The births were celebrated on the imperial coinage.[166]

Early rule

Bust of Marcus Aurelius, Louvre

Soon after the emperors' accession, Marcus' eleven-year-old daughter, Annia Lucilla, was betrothed to Lucius (in spite of the fact that he was, formally, her uncle).[167] At the ceremonies commemorating the event, new provisions were made for the support of poor children, along the lines of earlier imperial foundations.[168] Marcus and Lucius proved popular with the people of Rome, who strongly approved of their civiliter ("lacking pomp") behavior. The emperors permitted free speech, evidenced by the fact that the comedy writer Marullus was able to criticize them without suffering retribution. As the biographer wrote, "No one missed the lenient ways of Pius."[169]

Marcus replaced a number of the empire's major officials. The ab epistulis Sextus Caecilius Crescens Volusianus, in charge of the imperial correspondence, was replaced with Titus Varius Clemens. Clemens was from the frontier province of Pannonia and had served in the war in Mauretania. Recently, he had served as procurator of five provinces. He was a man suited for a time of military crisis.[170] Lucius Volusius Maecianus, Marcus ' former tutor, had been prefectural governor of Egypt at Marcus' accession. Maecianus was recalled, made senator, and appointed prefect of the treasury (aerarium Saturni). He was made consul soon after.[171] Fronto's son-in-law, Gaius Aufidius Victorinus, was appointed governor of Germania Superior.[172]

Fronto returned to his Roman townhouse at dawn on 28 March, having left his home in Cirta as soon as news of his pupils' accession reached him. He sent a note to the imperial freedman Charilas, asking if he could call on the emperors. Fronto would later explain that he had not dared to write the emperors directly.[173] The tutor was immensely proud of his students. Reflecting on the speech he had written on taking his consulship in 143, when he had praised the young Marcus, Fronto was ebullient: "There was then an outstanding natural ability in you; there is now perfected excellence. There was then a crop of growing corn; there is now a ripe, gathered harvest. What I was hoping for then, I have now. The hope has become a reality."[174] Fronto called on Marcus Aurelius alone; neither thought to invite Lucius.[175]

Lucius was less esteemed by Fronto than his brother, as his interests were on a lower level. Lucius asked Fronto to adjudicate in a dispute he and his friend Calpurnius were having on the relative merits of two actors.[176] Marcus told Fronto of his reading—Coelius and a little Cicero—and his family. His daughters were in Rome with their great-great-aunt Matidia; Marcus thought the evening air of the country was too cold for them. He asked Fronto for "some particularly eloquent reading matter, something of your own, or Cato, or Cicero, or Sallust or Gracchus—or some poet, for I need distraction, especially in this kind of way, by reading something that will uplift and diffuse my pressing anxieties."[177]

Marcus' early reign proceeded smoothly; he was able to give himself wholly to philosophy and the pursuit of popular affection.[178] Soon, however, he would find he had many anxieties. It would mean the end of the felicitas temporum ("happy times") that the coinage of 161 had proclaimed.[179]

Tiber Island seen at a forty-year high-water mark of the Tiber, December 2008

In either autumn 161 or spring 162,[notes 12] the Tiber overflowed its banks, flooding much of Rome. It drowned many animals, leaving the city in famine. Marcus and Lucius gave the crisis their personal attention.[181][notes 13] In other times of famine, the emperors are said to have provided for the Italian communities out of the Roman granaries.[183]

Fronto's letters continued through Marcus' early reign. Fronto felt that, because of Marcus' prominence and public duties, lessons were more important now than they had ever been before. He believed Marcus was "beginning to feel the wish to be eloquent once more, in spite of having for a time lost interest in eloquence".[184] Fronto would again remind his pupil of the tension between his role and his philosophic pretensions: "Suppose, Caesar, that you can attain to the wisdom of Cleanthes and Zeno, yet, against your will, not the philosopher's woolen cape."[185]

The early days of Marcus' reign were the happiest of Fronto's life: Marcus was beloved by the people of Rome, an excellent emperor, a fond pupil, and, perhaps most importantly, as eloquent as could be wished.[186] Marcus had displayed rhetorical skill in his speech to the senate after an earthquake at Cyzicus. It had conveyed the drama of the disaster, and the senate had been awed: "Not more suddenly or violently was the city stirred by the earthquake than the minds of your hearers by your speech." Fronto was hugely pleased.[187]

War with Parthia (161–166)

Coin of Vologases IV, king of Parthia, from 152/53

On his deathbed, Antoninus Pius spoke of nothing but the state and the foreign kings who had wronged him.[188] One of those kings, Vologases IV of Parthia, made his move in late summer or early autumn 161.[189] Vologases entered the Kingdom of Armenia (then a Roman client state), expelled its king and installed his own—Pacorus, an Arsacid like himself.[190] The governor of Cappadocia, the frontline in all Armenian conflicts, was Marcus Sedatius Severianus, a Gaul with much experience in military matters.[191]

Convinced by the prophet Alexander of Abonutichus that he could defeat the Parthians easily and win glory for himself,[192] Severianus led a legion (perhaps the IX Hispana[193]) into Armenia, but was trapped by the great Parthian general Chosrhoes at Elegia, a town just beyond the Cappadocian frontiers, high up past the headwaters of the Euphrates. After Severianus made some unsuccessful efforts to engage Chosrhoes, he committed suicide, and his legion was massacred. The campaign had lasted only three days.[194]

There was threat of war on other frontiers as well—in Britain, and in Raetia and Upper Germany, where the Chatti of the Taunus mountains had recently crossed over the limes.[195] Marcus was unprepared. Antoninus seems to have given him no military experience; the biographer writes that Marcus spent the whole of Antoninus' twenty-three-year reign at his emperor's side and not in the provinces, where most previous emperors had spent their early careers.[196][notes 14]

More bad news arrived: the Syrian governor's army had been defeated by the Parthians, and retreated in disarray.[198] Reinforcements were dispatched for the Parthian frontier. P. Julius Geminius Marcianus, an African senator commanding X Gemina at Vindobona (Vienna), left for Cappadocia with detachments from the Danubian legions.[199] Three full legions were also sent east: I Minervia from Bonn in Upper Germany,[200]II Adiutrix from Aquincum,[201] and V Macedonica from Troesmis.[202]

The northern frontiers were strategically weakened; frontier governors were told to avoid conflict wherever possible.[203]M. Annius Libo, Marcus' first cousin, was sent to replace the Syrian governor. His first consulship was in 161, so he was probably in his early thirties,[204] and, as a patrician, he lacked military experience. Marcus had chosen a reliable man rather than a talented one.[205]

Aureus of Marcus Aurelius (AD 166). On the reverse, Victoria is holding a shield inscribed 'Vic(toria) Par(thica)', referring to his victory against the Parthians.[206]

Marcus took a four-day public holiday at Alsium, a resort town on the coast of Etruria. He was too anxious to relax. Writing to Fronto, he declared that he would not speak about his holiday.[207] Fronto replied: "What? Do I not know that you went to Alsium with the intention of devoting yourself to games, joking, and complete leisure for four whole days?"[208] He encouraged Marcus to rest, calling on the example of his predecessors (Antoninus had enjoyed exercise in the palaestra, fishing, and comedy),[209] going so far as to write up a fable about the gods' division of the day between morning and evening—Marcus Aurelius had apparently been spending most of his evenings on judicial matters instead of at leisure.[210] Marcus could not take Fronto's advice. "I have duties hanging over me that can hardly be begged off," he wrote back.[211] Marcus Aurelius put on Fronto's voice to chastise himself: "'Much good has my advice done you', you will say!" He had rested, and would rest often, but "—this devotion to duty! Who knows better than you how demanding it is!"[212]

Fronto sent Marcus a selection of reading material,[214] and, to settle his unease over the course of the Parthian war, a long and considered letter, full of historical references. In modern editions of Fronto's works, it is labeled De bello Parthico (On the Parthian War). There had been reverses in Rome's past, Fronto writes,[215] but, in the end, Romans had always prevailed over their enemies: "Always and everywhere [Mars] has changed our troubles into successes and our terrors into triumphs."[216]

Over the winter of 161–162, news that a rebellion was brewing in Syria arrived and it was decided that Lucius should direct the Parthian war in person. He was stronger and healthier than Marcus, the argument went, and thus more suited to military activity.[217] Lucius' biographer suggests ulterior motives: to restrain Lucius' debaucheries, to make him thrifty, to reform his morals by the terror of war, and to realize that he was an emperor.[218][notes 15] Whatever the case, the senate gave its assent, and, in the summer of 162, Lucius left. Marcus would remain in Rome, as the city "demanded the presence of an emperor".[220]

Lucius spent most of the campaign in Antioch, though he wintered at Laodicea and summered at Daphne, a resort just outside Antioch.[221] Critics declaimed Lucius' luxurious lifestyle.[222] He had taken to gambling, they said; he would "dice the whole night through".[223] He enjoyed the company of actors.[224][notes 16] Libo died early in the war; perhaps Lucius had murdered him.[226]

Marble statue of Lucilla, 150–200 AD, Bardo National Museum, Tunisia

In the middle of the war, perhaps in autumn 163 or early 164, Lucius made a trip to Ephesus to be married to Marcus' daughter Lucilla.[227] Marcus moved up the date; perhaps he had already heard of Lucius' mistress Panthea.[228] Lucilla's thirteenth birthday was in March 163; whatever the date of her marriage, she was not yet fifteen.[229] Lucilla was accompanied by her mother Faustina and Verus' uncle (his father's half-brother) M. Vettulenus Civica Barbarus,[230] who was made comes Augusti, "companion of the emperors". Marcus may have wanted Civica to watch over Verus, the job Libo had failed at.[231] Marcus may have planned to accompany them all the way to Smyrna (the biographer says he told the senate he would), but this did not happen.[232] He only accompanied the group as far as Brundisium, where they boarded a ship for the east.[233] He returned to Rome immediately thereafter, and sent out special instructions to his proconsuls not to give the group any official reception.[234]

The Armenian capital Artaxata was captured in 163.[235] At the end of the year, Lucius took the title Armeniacus, despite having never seen combat; Marcus declined to accept the title until the following year.[236] When Lucius was hailed as imperator again, however, Marcus did not hesitate to take the Imperator II with him.[237]

Occupied Armenia was reconstructed on Roman terms. In 164, a new capital, Kaine Polis ('New City'), replaced Artaxata.[238] A new king was installed: a Roman senator of consular rank and Arsacid descent, Gaius Julius Sohaemus. He may not even have been crowned in Armenia; the ceremony may have taken place in Antioch, or even Ephesus.[239] Sohaemus was hailed on the imperial coinage of 164 under the legend .mw-parser-output .smallcaps{font-variant:small-caps}Rex armeniis Datus: Lucius sat on a throne with his staff while Sohaemus stood before him, saluting the emperor.[240]

In 163, the Parthians intervened in Osroene, a Roman client in upper Mesopotamia centered on Edessa, and installed their own king on its throne.[241] In response, Roman forces were moved downstream, to cross the Euphrates at a more southerly point.[242] Before the end of 163, however, Roman forces had moved north to occupy Dausara and Nicephorium on the northern, Parthian bank.[243] Soon after the conquest of the north bank of the Euphrates, other Roman forces moved on Osroene from Armenia, taking Anthemusia, a town southwest of Edessa.[244]

In 165, Roman forces moved on Mesopotamia. Edessa was re-occupied, and Mannus, the king deposed by the Parthians, was re-installed.[245] The Parthians retreated to Nisibis, but this too was besieged and captured. The Parthian army dispersed in the Tigris.[246] A second force, under Avidius Cassius and the III Gallica, moved down the Euphrates, and fought a major battle at Dura.[247]

By the end of the year, Cassius' army had reached the twin metropolises of Mesopotamia: Seleucia on the right bank of the Tigris and Ctesiphon on the left. Ctesiphon was taken and its royal palace set to flame. The citizens of Seleucia, still largely Greek (the city had been commissioned and settled as a capital of the Seleucid Empire, one of Alexander the Great's successor kingdoms), opened its gates to the invaders. The city was sacked nonetheless, leaving a black mark on Lucius' reputation. Excuses were sought, or invented: the official version had it that the Seleucids broke faith first.[248]

Cassius' army, although suffering from a shortage of supplies and the effects of a plague contracted in Seleucia, made it back to Roman territory safely.[249] Lucius took the title Parthicus Maximus, and he and Marcus were hailed as imperatores again, earning the title 'imp. III'.[250] Cassius' army returned to the field in 166, crossing over the Tigris into Media. Lucius took the title 'Medicus',[251] and the emperors were again hailed as imperatores, becoming 'imp. IV' in imperial titulature. Marcus took the Parthicus Maximus now, after another tactful delay.[252]

War with Germanic tribes (166–180)

The Roman Empire at the death of Marcus Aurelius in 180. His annexation of lands of the Marcomanni and the Jazyges – perhaps to be provincially called Marcomannia and Sarmatia[253] – was cut short in 175 by the revolt of Avidius Cassius and by his death.[254] The light pink territory represents Roman dependencies - Armenia, Georgia, Iberia, and Albania.

Aureus of Marcus Aurelius (AD 176-177). The pile of trophies on the reverse celebrates the end of the Marcomannic Wars.[255]

During the early 160s, Fronto's son-in-law Victorinus was stationed as a legate in Germany. He was there with his wife and children (another child had stayed with Fronto and his wife in Rome).[256] The condition on the northern frontier looked grave. A frontier post had been destroyed, and it looked like all the peoples of central and northern Europe were in turmoil. There was corruption among the officers: Victorinus had to ask for the resignation of a legionary legate who was taking bribes.[257]

Experienced governors had been replaced by friends and relatives of the imperial family. Lucius Dasumius Tullius Tuscus, a distant relative of Hadrian, was in Upper Pannonia, succeeding the experienced Marcus Nonius Macrinus. Lower Pannonia was under the obscure Tiberius Haterius Saturnius. Marcus Servilius Fabianus Maximus was shuffled from Lower Moesia to Upper Moesia when Marcus Iallius Bassus had joined Lucius in Antioch. Lower Moesia was filled by Pontius Laelianus' son. The Dacias were still divided in three, governed by a praetorian senator and two procurators. The peace could not hold long; Lower Pannonia did not even have a legion.[258]

Starting in the 160s, Germanic tribes and other nomadic people launched raids along the northern border, particularly into Gaul and across the Danube. This new impetus westwards was probably due to attacks from tribes further east. A first invasion of the Chatti in the province of Germania Superior was repulsed in 162.[259]

Far more dangerous was the invasion of 166, when the Marcomanni of Bohemia, clients of the Roman Empire since 19 AD, crossed the Danube together with the Lombards and other Germanic tribes.[260] Soon thereafter, the Iranian Sarmatians attacked between the Danube and the Theiss rivers.[261]

The Costoboci, coming from the Carpathian area, invaded Moesia, Macedonia, and Greece. After a long struggle, Marcus managed to push back the invaders. Numerous members of Germanic tribes settled in frontier regions like Dacia, Pannonia, Germany, and Italy itself. This was not a new thing, but this time the numbers of settlers required the creation of two new frontier provinces on the left shore of the Danube, Sarmatia and Marcomannia, including today's Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Hungary. Some Germanic tribes who settled in Ravenna revolted and managed to seize possession of the city. For this reason, Marcus decided not only against bringing more barbarians into Italy, but even banished those who had previously been brought there.[262]

Legal and administrative work

Bust of Marcus Aurelius in the Liebieghaus, Frankfurt

Like many emperors, Marcus spent most of his time addressing matters of law such as petitions and hearing disputes,[263] but unlike many of his predecessors, he was already proficient in imperial administration when he assumed power.[264] He took great care in the theory and practice of legislation. Professional jurists called him "an emperor most skilled in the law"[265] and "a most prudent and conscientiously just emperor".[266] He showed marked interest in three areas of the law: the manumission of slaves, the guardianship of orphans and minors, and the choice of city councillors (decuriones).[267]

Marcus showed a great deal of respect to the Roman Senate and routinely asked them for permission to spend money even though he did not need to do so as the absolute ruler of the Empire.[268] In one speech, Marcus himself reminded the Senate that the imperial palace where he lived was not truly his possession but theirs.[269]

In 168, he revalued the denarius, increasing the silver purity from 79% to 82%—the actual silver weight increasing from 2.57 grams to 2.67 grams. However, two years later he reverted to the previous values because of the military crises facing the empire.[157]

A possible contact with Han China occurred in 166 when a Roman traveller visited the Han court, claiming to be an ambassador representing a certain Andun (Chinese: 安敦), ruler of Daqin, who can be identified either with Marcus or his predecessor Antoninus.[270][271][272] In addition to Republican-era Roman glasswares found at Guangzhou along the South China Sea,[273] Roman golden medallions made during the reign of Antoninus and perhaps even Marcus have been found at Óc Eo, Vietnam, then part of the Kingdom of Funan near the Chinese province of Jiaozhi (in northern Vietnam). This may have been the port city of Kattigara, described by Ptolemy (c. 150) as being visited by a Greek sailor named Alexander and laying beyond the Golden Chersonese (i.e. Malay Peninsula).[274][275] Roman coins from the reigns of Tiberius to Aurelian have been found in Xi'an, China (site of the Han capital Chang'an), although the far greater amount of Roman coins in India suggests the Roman maritime trade for purchasing Chinese silk was centered there, not in China or even the overland Silk Road running through Persia.[276]

Plague

When Lucius' army returned from the war with Parthia, it brought with it plague. Cases of "Antonine Plague", also known as "the Plague of Galen", occurred throughout the Empire for years. The pandemic is believed to have been either smallpox or measles,[277][278] but the true cause remains undetermined. The epidemic may have claimed the life of Lucius, who died in 169. The disease broke out again nine years later, according to the Roman historian Dio Cassius, causing up to 2,000 deaths a day in Rome, one-quarter of those who were affected, giving the disease a mortality rate of about 25%.[279] The total deaths have been estimated at five million,[280] and the disease killed as much as one-third of the population in some areas and devastated the Roman army.[281]

Death and succession (180)

Last Words of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius (1844) by Eugène Delacroix

Castings of the busts of Antonius Pius (left), Marcus Aurelius (centre), and Clodius Albinus (right), Pushkin Museum, Moscow

Marcus died on 17 March 180 due to natural causes in the city of Vindobona (modern Vienna). He was immediately deified and his ashes were returned to Rome, where they rested in Hadrian's mausoleum (modern Castel Sant'Angelo) until the Visigoth sack of the city in 410. His campaigns against Germans and Sarmatians were also commemorated by a column and a temple built in Rome.[282] Some scholars consider his death to be the end of the Pax Romana.[283]Edward Gibbon characterises Marcus, in his work "The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire", as the last fair ruler during the Pax Romana:

The vast extent of the Roman Empire was governed by absolute power, under the guidance of virtue and wisdom. The armies were restrained by the firm but gentle hand of four successive emperors, whose characters and authority commanded respect. The forms of the civil administration were carefully preserved by Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, and the Antonines, who delighted in the image of liberty, and were pleased with considering themselves as the accountable ministers of the laws.[284][285][286]

Niccolò Machiavelli writes of Titus and the Nerva-Antonine emperors:

Titus, Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus and Marcus had no need of praetorian cohorts, or of countless legions to guard them, but were defended by their own good lives, the good-will of their subjects, and the attachment of the senate. (...) From the study of this history we may also learn how a good government is to be established; for while all the emperors who succeeded to the throne by birth, except Titus, were bad, all were good who succeeded by adoption, as in the case of the five from Nerva to Marcus. But as soon as the empire fell once more to the heirs by birth, its ruin recommenced.[287]

Marcus was succeeded by his son Commodus, whom he had named Caesar in 166 and with whom he had jointly ruled since 177.[288] Biological sons of the emperor, if there were any, were considered heirs;[289] however, it was only the second time that a "non-adoptive" son had succeeded his father, the only other having been a century earlier when Vespasian was succeeded by his son Titus. Historians have criticized the succession to Commodus, citing Commodus' erratic behavior and lack of political and military acumen.[288] At the end of his history of Marcus' reign, Cassius Dio wrote an encomium to the emperor, and described the transition to Commodus in his own lifetime with sorrow:

(Marcus) did not meet with the good fortune that he deserved, for he was not strong in body and was involved in a multitude of troubles throughout practically his entire reign. But for my part, I admire him all the more for this very reason, that amid unusual and extraordinary difficulties he both survived himself and preserved the empire. Just one thing prevented him from being completely happy, namely, that after rearing and educating his son in the best possible way he was vastly disappointed in him. This matter must be our next topic; for our history now descends from a kingdom of gold to one of iron and rust, as affairs did for the Romans of that day.

- –Cassius Dio lxxi. 36.3–4[290]

Dio adds that from Marcus' first days as counsellor to Antoninius to his final days as emperor of Rome, "he remained the same (person) and did not change in the least."[291]

Michael Grant, in The Climax of Rome, writes of Commodus:

The youth turned out to be very erratic, or at least so anti-traditional that disaster was inevitable. But whether or not Marcus ought to have known this to be so, the rejections of his son's claims in favour of someone else would almost certainly have involved one of the civil wars which were to proliferate so disastrously around future successions.[292]

Legacy and reputation

Marcus acquired the reputation of a philosopher king within his lifetime, and the title would remain his after death; both Dio and the biographer call him "the philosopher".[293][294] Christians such as Justin Martyr, Athenagoras, and Melito also gave him the title.[295] The last named went so far as to call him "more philanthropic and philosophic" than Antoninus and Hadrian, and set him against the persecuting emperors Domitian and Nero to make the contrast bolder.[296] "Alone of the emperors," wrote the historian Herodian, "he gave proof of his learning not by mere words or knowledge of philosophical doctrines but by his blameless character and temperate way of life."[297]Iain King concludes that Marcus' legacy is tragic, because the emperor's "Stoic philosophy—which is about self-restraint, duty, and respect for others—was so abjectly abandoned by the imperial line he anointed on his death".[298]

Attitude towards Christians

In the first two centuries of the Christian era, it was local Roman officials who were largely responsible for the persecution of Christians. In the second century, the emperors treated Christianity as a local problem to be dealt with by their subordinates.[299] The number and severity of persecutions of Christians in various locations of the empire seemingly increased during the reign of Marcus. The extent to which Marcus himself directed, encouraged, or was aware of these persecutions is unclear and much debated by historians.[300] According to Edward Gibbon, with the onset of the Germanic war, his treatment of the Christians degraded with increased persecutions uncharacteristic of the previous years of his reign and those of his predecessors.[301]

Marriage and children

Commodus as Hercules, Capitoline Museums

Marcus married his first cousin Faustina in 145. During their 30-year marriage, they had at least 13 children,[119][302] including two sets of twins.[119][303] One son and four daughters outlived their father:[304]

- Domitia Faustina (147 – 151)[119][131][305]

- Titus Aelius Antoninus (149)[122][303][306]

- Titus Aelius Aurelius (149)[122][303][306]

Annia Aurelia Galeria Lucilla (150[307][305] – 182[308]), married her father's co-ruler Lucius Verus[131]

Annia Galeria Aurelia Faustina (born 151)[127]

- Tiberius Aelius Antoninus (born 152, died before 156)[127]

- Unknown child (died before 158)[129]

Annia Aurelia Fadilla (born 159[305][129])[131]

Annia Cornificia Faustina Minor (born 160[305][129])[131]

- Titus Aurelius Fulvus Antoninus (161 – 165), elder twin brother of Commodus[306]

- Lucius Aurelius Commodus Antoninus (Commodus) (161 – 192),[309] twin brother of Titus Aurelius Fulvus Antoninus, later emperor[306][310]

Marcus Annius Verus Caesar (162[311] – 169[302][312])[131]

- Hadrianus[131]

Vibia Aurelia Sabina (170[306] – died before 217[313])[131]

Writings

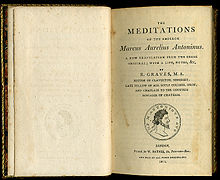

First page of the 1792 English translation by Richard Graves

While on campaign between 170 and 180, Marcus wrote his Meditations in Greek as a source for his own guidance and self-improvement. The original title of this work, if it had one, is unknown. "Meditations"–as well as other titles including "To Himself"–were adopted later. He had a logical mind and his notes were representative of Stoic philosophy and spirituality. Meditations is still revered as a literary monument to a government of service and duty. According to Hays, the book was a favourite of Christina of Sweden, Frederick the Great, John Stuart Mill, Matthew Arnold, and Goethe, and is admired by modern figures such as Wen Jiabao and Bill Clinton.[314] It has been considered by many commentators to be one of the greatest works of philosophy.[315]

It is not known how widely Marcus' writings were circulated after his death. There are stray references in the ancient literature to the popularity of his precepts, and Julian the Apostate was well aware of his reputation as a philosopher, though he does not specifically mention Meditations.[316] It survived in the scholarly traditions of the Eastern Church and the first surviving quotes of the book, as well as the first known reference of it by name ("Marcus' writings to himself") are from Arethas of Caesarea in the 10th century and in the Byzantine Suda (perhaps inserted by Arethas himself). It was first published in 1558 in Zurich by Wilhelm Xylander (ne Holzmann), from a manuscript reportedly lost shortly afterwards.[317] The oldest surviving complete manuscript copy is in the Vatican library and dates to the 14th century.[318]

Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius

Aureus of Marcus Aurelius (AD December 173- June 174), with his equestrian statue on the reverse.[319]

The Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius in Rome is the only Roman equestrian statue which has survived into the modern period.[320] This is perhaps due to it being wrongly identified during the Middle Ages as a depiction of the Christian emperor Constantine the Great and hence was spared destruction, unlike some other statues associated with paganism. Crafted of bronze in circa 175 AD, it stands 11.6 ft (3.5 m) and is now located in the Capitoline Museums of Rome. The emperor's hand is outstretched in an act of clemency offered to a bested enemy, while his weary facial expression due to the stress of leading Rome into nearly constant battles perhaps represents a break with the classical tradition of sculpture.[321]

Column of Marcus Aurelius

Marcus' victory column, established in Rome either in his last few years of life or after his reign and completed in 193 AD, was built to commemorate his victory over the Sarmatians and Germanic tribes in 176 AD. A spiral of carved reliefs wraps around the column, showing scenes from his military campaigns. A statue of Marcus had stood atop the column but disappeared during the Middle Ages. It was replaced with a statue of Saint Paul in 1589 by pope Sixtus V.[322] The column of Marcus and the column of Trajan are often compared by scholars given how they are both Doric in style, had a pedestal at the base, had sculpted friezes depicting their respective military victories, and a statue on top.[323]

The Column of Marcus Aurelius in Piazza Colonna

Detail from the column. The five horizontal slits (visible in the larger version) allow light into the internal spiral staircase.

German council of war depicted on the column – considered early evidence of what would become known as the Thing (assembly)

The column, right, in the background of Panini's painting of the Palazzo Montecitorio, with the base of the Column of Antoninus Pius in the right foreground (1747)

An inscription describing the restoration by pope Sixtus V

Notes

^ Cassius Dio asserts that the Annii were near-kin of Hadrian, and that it was to these familial ties that they owed their rise to power.[20] The precise nature of these kinship ties is nowhere stated. One conjectural bond runs through Annius Verus (II). Verus' wife Rupilia Faustina was the daughter of the consular senator Libo Rupilius Frugi and an unnamed mother. It has been hypothesized Rupilia Faustina's mother was Matidia, who was also the mother (presumably through another marriage) of Vibia Sabina, Hadrian's wife.[21]

^ Farquharson dates his death to 130, when Marcus was nine.[27]

^ Birley amends the text of the HA Marcus from "Eutychius" to "Tuticius".[41]

^ Commodus was a known consumptive at the time of his adoption, so Hadrian may have intended Marcus' eventual succession anyway.[52]

^ The manuscript is corrupt here.[75]

^ Modern scholars have not offered as positive an assessment. His second modern editor, Niebhur, thought him stupid and frivolous; his third editor, Naber, found him contemptible.[92] Historians have seen him as a "pedant and a bore", his letters offering neither the running political analysis of a Cicero or the conscientious reportage of a Pliny.[93] Recent prosopographic research has rehabilitated his reputation, though not by much.[94]

^ Champlin notes that Marcus' praise of him in the Meditations is out of order (he is praised immediately after Diognetus, who had introduced Marcus to philosophy), giving him special emphasis.[114]

^ Although part of the biographer's account of Lucius is fictionalized (probably to mimic Nero, whose birthday Lucius shared[133]) and another part poorly compiled from a better biographical source,[134] scholars have accepted these biographical details as accurate.[135]

^ These name-swaps have proven so confusing that even the Historia Augusta, our main source for the period, cannot keep them straight.[150] The 4th-century ecclesiastical historian Eusebius of Caesarea shows even more confusion.[151] The mistaken belief that Lucius had the name "Verus" before becoming emperor has proven especially popular.[152]

^ There was, however, much precedent. The consulate was a twin magistracy, and earlier emperors had often had a subordinate lieutenant with many imperial offices (under Antoninus, the lieutenant had been Marcus). Many emperors had planned a joint succession in the past: Augustus planned to leave Gaius Caesar and Lucius Caesar as joint emperors on his death; Tiberius wished to have Gaius Caligula and Tiberius Gemellus do so as well; Claudius left the empire to Nero and Britannicus, imagining that they would accept equal rank. All of these arrangements had ended in failure, either through premature death (Gaius and Lucius Caesar) or judicial murder (Gemellus by Caligula and Britannicus by Nero).[152]

^ The biographer relates the scurrilous (and, in the judgment of Anthony Birley, untrue) rumor that Commodus was an illegitimate child born of a union between Faustina and a gladiator.[164]

^ Because both Lucius and Marcus are said to have taken active part in the recovery (HA Marcus viii. 4–5), the flood must have happened before Lucius' departure for the east in 162; because it appears in the biographer's narrative after Antoninus' funeral has finished and the emperors have settled into their offices, it must not have occurred in the spring of 161. A date in autumn 161 or spring 162 is probable, and, given the normal seasonal distribution of Tiber flooding, the most probable date is in spring 162.[180] (Birley dates the flood to autumn 161.[175])

^ Since 15 AD, the river had been administered by a Tiber Conservancy Board, with a consular senator at its head and a permanent staff. In 161, the curator alevi Tiberis et riparum et cloacarum urbis ("Curator of the Tiber Bed and Banks and the City Sewers") was A. Platorius Nepos, son or grandson of the builder of Hadrian's Wall, whose name he shares. He probably had not been particularly incompetent. A more likely candidate for that incompetence is Nepos' likely predecessor, M. Statius Priscus. A military man and consul for 159, Priscus probably looked on the office as little more than "paid leave".[182]

^ Alan Cameron adduces the 5th-century writer Sidonius Apollinaris's comment that Marcus commanded "countless legions" vivente Pio (while Antoninus was alive) while contesting Birley's contention that Marcus had no military experience. (Neither Apollinaris nor the Historia Augusta (Birley's source) are particularly reliable on 2nd-century history.[197])

^ Birley believes there is some truth in these considerations.[219]

^ The whole section of the vita dealing with Lucius' debaucheries (HA Verus iv. 4–6.6), however, is an insertion into a narrative otherwise entirely cribbed from an earlier source. Most of the details are fabricated by the biographer himself, relying on nothing better than his own imagination.[225]

Citations

All citations to the Historia Augusta are to individual biographies, and are marked with a "HA". Citations to the works of Fronto are cross-referenced to C.R. Haines' Loeb edition.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 229–30. The thesis of single authorship was first proposed in H. Dessau's "Über Zeit und Persönlichkeit der Scriptoes Historiae Augustae" (in German), Hermes 24 (1889), pp. 337ff.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 230. On the HA Verus, see Barnes, pp. 65–74.

^ Beard; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 226.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 227.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, pp. 228–29, 253.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, pp. 227–28.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 228.

^ Mattingly & Sydenham, Roman Imperial Coinage, vol. III, p. 77.

^ Gnecchi, Medaglioni Romani, p. 33.

^ Magill, p. 693.

^ ab Historia MA I.9–10

^ Van Ackeren, p. 139.

^ abc Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 33.

^ Dio 69.21.1; HA Marcus i. 10; McLynn, Marcus Aurelius: Warrior, Philosopher, Emperor, p. 24.

^ Dio lxix.21.1; HA Marcus i. 9; McLynn, Marcus Aurelius: Warrior, Philosopher, Emperor, p. 24.

^ Van Ackeren, p. 78.

^ Dean, p. 32.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 49.

^ HA Marcus i. 2, 4; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 28; McLynn, p. 14.

^ Dio 69.21.2, 71.35.2–3; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 31.

^ Codex Inscriptionum Latinarum 14.3579 Archived 29 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine.; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 29; McLynn, pp. 14, 575 n. 53, citing Ronald Syme, Roman Papers 1.244.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 29; McLynn, Marcus Aurelius: Warrior, Philosopher, Emperor, p. 14.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 29, citing Pliny, Epistulae 8.18.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 30.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, pp. 31, 44.

^ ab Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 31.

^ Farquharson, 1.95–96.

^ Meditations 1.1, qtd. and tr. Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 31.

^ HA Marcus ii. 1 and Meditations v. 4, qtd. in Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 32.

^ Meditations i. 3, qtd. in Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 35.

^ Meditations i. 17.7, qtd. and tr. Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 35.

^ Ad Marcum Caesarem ii. 8.2 (= Haines 1.142), qtd. and tr. Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 31.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, pp. 31–32.

^ Meditations i. 1, qtd. and tr. Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 35.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 35.

^ Meditations i. 17.2; Farquharson, 1.102; McLynn, Marcus Aurelius: Warrior, Philosopher, Emperor, p. 23; cf. Meditations i. 17.11; Farquharson, 1.103.

^ McLynn, Marcus Aurelius: Warrior, Philosopher, Emperor, 20–21.

^ Meditations 1.4; McLynn, Marcus Aurelius: Warrior, Philosopher, Emperor, p. 20.

^ HA Marcus ii. 2, iv. 9; Meditations i. 3; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 37; McLynn, Marcus Aurelius: Warrior, Philosopher, Emperor, pp. 21–22.

^ HA Marcus ii. 6; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 38; McLynn, Marcus Aurelius: Warrior, Philosopher, Emperor, p. 21.

^ Birley, Lives of the Later Caesars, pp. 109, 109 n.8; Marcus Aurelius, pp. 40, 270 n.27, citing Bonner Historia-Augusta Colloquia 1966/7, pp. 39ff.

^ HA Marcus ii. 3; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, pp. 40, 270 n.27.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 40, citing Aelius Aristides, Oratio 32 K; McLynn, Marcus Aurelius: Warrior, Philosopher, Emperor, p. 21.

^ Meditations i. 10; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 40; McLynn, Marcus Aurelius: Warrior, Philosopher, Emperor, p. 22.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, pp. 40, 270 n.28, citing A.S.L. Farquharson, The Meditations of Marcus Antoninus (Oxford, 1944) ii. 453.

^ Portrait of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, pp. 41–42.

^ HA Hadrian xiii. 10, qtd. in Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 42.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 42. Van Ackeren, 142. On the succession to Hadrian, see also: T.D. Barnes, "Hadrian and Lucius Verus", Journal of Roman Studies 57:1–2 (1967): 65–79; J. VanderLeest, "Hadrian, Lucius Verus, and the Arco di Portogallo", Phoenix 49:4 (1995): pp. 319–30.

^ HA Aelius vi. 2-3

^ HA Hadrian xxiii. 15–16; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 45; "Hadrian to the Antonines", 148.

^ Dio, lxix.17.1; HA Aelius, iii. 7, iv. 6, vi. 1–7; Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", p. 147.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 46. Date: Birley, "Hadrian to the Antonines", p. 148.

^ Weigel.

^ Dio 69.21.1; HA Hadrian xxiv. 1; HA Aelius vi. 9; HA Antoninus Pius iv. 6–7; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, pp. 48–49.

^ HA Marcus v. 3; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 49.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, pp. 49–50.

^ HA Marcus v. 6–8, qtd. and tr. Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 50.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, pp. 80–81.

^ Dio 69.22.4; HA Hadrian xxv. 5–6; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, pp. 50–51. Hadrian's suicide attempts: Dio, lxix. 22.1–4; HA Hadrian xxiv. 8–13.

^ HA Hadrian xxv. 7; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 53.

^ HA Antoninus Pius v. 3, vi. 3; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, pp. 55–56; "Hadrian to the Antonines", p. 151.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 55; "Hadrian to the Antonines", p. 151.

^ Mattingly & Sydenham, Roman Imperial Coinage, vol. III, p. 108.

^ HA Marcus vi. 2; Verus ii. 3–4; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, pp. 53–54.

^ Dio 71.35.5; HA Marcus vi. 3; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 56.

^ Meditations vi. 30, qtd. and tr. Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 57; cf. Marcus Aurelius, p. 270 n.9, with notes on the translation.

^ ab HA Marcus vi. 3; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, 57.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, pp. 57, 272 n.10, citing Codex Inscriptionum Latinarum 6.32, 6.379, cf. Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae 360.

^ Meditations 5.16, qtd. and tr. Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 57.

^ Meditations 8.9, qtd. and tr. Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 57.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, pp. 57–58.

^ Ad Marcum Caesarem iv. 7, qtd. and tr. Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 90.

^ HA Marcus vi. 5; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 58.

^ ab Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 89.

^ Ad Marcum Caesarem v. 1, qtd. and tr. Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 89.

^ Ad Marcum Caesarem 4.8, qtd. and tr. Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 89.

^ Dio 71.36.3; Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 89.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, pp. 90–91.

^ HA Antoninus Pius x. 2, qtd. and tr. Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 91.

^ Birley, Marcus Aurelius, p. 91.