砂拉越

| 砂拉越 Sarawak | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

綽號:犀鸟之乡[1] Bumi Kenyalang | |||

格言:团结、勤勉、奉献' Bersatu, Berusaha, Berbakti | |||

颂歌:《我的故鄉》[2] | |||

砂拉越 马来西亚其它州属 | |||

坐标:3°02′17″N 113°46′52″E / 3.0381°N 113.7811°E / 3.0381; 113.7811 | |||

| 首府 | 古晋市 | ||

| 省份 | 列表

| ||

| 政府[5][6] | |||

| • 州元首 | 泰益瑪目 | ||

| • 首席部长 | 阿邦佐哈里 (土保党) | ||

| 面积[7] | |||

| • 总数 | 124,450 平方公里(48,050 平方英里) | ||

| 人口(2015)[8] | |||

| • 总数 | 2,636,000 | ||

| • 密度 | 21/平方公里(55/平方英里) | ||

| 居民称谓 | 砂拉越人 | ||

人类发展指数 | |||

| • HDI (2015) | 0.757 (中等) (11th) | ||

| 时区 | MST[9] (UTC+8) | ||

| 邮政编码 | 93xxx[10] 至 98xxx[11] | ||

| 电话区号 | 082 (古晋)、 (三马拉汉) 083 (诗里阿曼)、 (木中) 084 (诗巫)、 (加帛)、 (泗里街)、 (沐膠) 085 (美里)、 (林夢)、 (马鲁帝)、 (老越) 086 (民都鲁)、 (布拉甲)[12] | ||

| 車牌 | QA 至 QK (古晋) QB (诗里阿曼) QC (三马拉汉) QL (林夢) QM (美里) QP (加帛) QR (泗里街) QS (诗巫) QT (民都鲁) QSG (砂拉越州政府)[13] | ||

| 汶莱帝國 | 15世纪–1841年[14] | ||

| 布鲁克王朝 | 1841年–1946年 | ||

| 日本軍事佔領 | 1941年–1945年 | ||

| 英属直轄殖民地 | 1946年–1963年 | ||

| 自治 | 1963年7月22日[15][16][17][18] | ||

馬來西亞協定[19] | 1963年9月16日a[20] | ||

| 網站 | 官方网站 | ||

a 儘管馬來西亞於1963年9月16日開始存在,8月31日(馬來亞獨立日)卻被選為馬來西亞的獨立日。 2010年以來,9月16日被認定為馬來西亞日。這是一個馬來西亞公共假期,為的是紀念北婆羅洲、馬來亞、砂拉越和新加坡以同等夥伴的地位參組馬來西亞。[21] | |||

砂拉越[註 1](馬來語:Sarawak,IPA: .mw-parser-output .IPA{font-family:"Charis SIL","Doulos SIL","Linux Libertine","Segoe UI","Lucida Sans Unicode","Code2000","Gentium","Gentium Alternative","TITUS Cyberbit Basic","Arial Unicode MS","IPAPANNEW","Chrysanthi Unicode","GentiumAlt","Bitstream Vera","Bitstream Cyberbit","Hiragino Kaku Gothic Pro","Lucida Grande",sans-serif;text-decoration:none!important}.mw-parser-output .IPA a:link,.mw-parser-output .IPA a:visited{text-decoration:none!important}[saˈrawaʔ]),旧译砂朥越、砂勞越、砂羅越或砂捞越,簡稱砂或砂州,马来语又稱作“犀鸟之乡”(Bumi Kenyalang),是马来西亚在婆罗洲领土上两个行政区域之一(另一个为沙巴州),也是全马面積最大的州。砂拉越州在行政、移民和司法制度上与马来西亚半岛的其他行政区明显不同。地理上砂拉越州位于婆罗洲西北,东北与沙巴州相邻,并把汶莱这一独立国家隔成两部分,而其南与印尼加里曼丹接壤。砂拉越州的首府古晋市是全州的经济和政治中心,州内还有美里、诗巫和民都鲁等大大小小的城市分布。根据2015年的人口估查,砂拉越州共有2,636,000人[8]。全州的气候类型是熱帶雨林氣候,生长着大片热带雨林,为各种各样的动植物提供了生存环境。以许多著名的洞穴系统而闻名的姆鲁山国家公园也位于砂拉越州。发源于依兰山脉的拉让江既是该州的重要河流,也是马来西亚最长的河流;其支流上的巴贡水电站是东南亚的大型水电站之一。砂拉越州的最高点为2,423米高的毛律山。

在尼亚洞发现了距今四万年前早期人类在砂拉越的居住遗迹。在公元八至十三世纪砂拉越,这一地区与古代中国维持着贸易往来。在十六世纪时这一地区开始受到汶萊帝國(渤泥国)的控制。1841年,英国探险家詹姆士·布鲁克从汶莱手中取得砂拉越(今古晋一带)的统治权,成为了独立的王国,并逐步将版图扩张至今天的范围。随着第二次世界大战太平洋战争的爆发,砂拉越在1941年被日本占领。战后的1946年,砂拉越又被划给英国成为了直轄殖民地,直到1963年7月22日才從英國取得自治權。同年9月16日,砂拉越與北婆羅洲(今沙巴)、新加坡(在1965年被驱逐出联邦)和马来亚联合邦(今马来西亚半岛或西马)组成今天的马来西亚。这一联邦体制的建立受到了邻国印尼的反对,并导致了两国陷入了长达三年的武装对抗。1966年8月对抗平息后的砂拉越又经历了砂共叛乱,这场叛乱直到1990年才停息。

砂拉越州呈现出富有代表性的民族特点、文化特色和多样化语言。砂拉越州的州元首称作“Yang di-Pertua Negeri”,而其政府首脑称为“首席部长”。砂拉越州的政府架构与西敏制相似,并在国内拥有最早的州議會制度。砂拉越州的官方语言为英语和马来语,并没有规定官方宗教。位于古晋的砂拉越博物馆是婆罗洲历史最悠久的博物馆。砂拉越还以它的传统乐器沙貝而闻名。为期三天的熱帶雨林世界音樂節(RWMF,古晋)便是在砂拉越州举行。同时砂拉越州也是全国唯一庆祝达雅丰收节的地方。

砂拉越州蕴藏着大量自然资源,其经济发展在很大程度上属于外向出口型,特别是在石油、天然气、木材和油棕方面。砂拉越州还有制造业、能源和旅游等产业。

目录

1 词源

2 歷史

2.1 史前

2.2 汶莱帝國

2.3 布鲁克王朝

2.4 日本军事占领及盟军收复

2.5 英属直轄殖民地

2.6 自治和馬來西亞

3 政治

3.1 政府

3.2 行政区划

3.2.1 省份

3.2.2 縣

4 保安

4.1 领土争端

5 環境

5.1 地理

5.2 生物多樣性

5.2.1 环保课題

6 經濟

6.1 能源

6.2 旅游

7 基础设施

7.1 交通

7.1.1 陆路

7.1.2 空路

7.1.3 水路

7.1.4 铁路

7.2 医疗

7.3 教育

8 人口与族裔

8.1 伊班族

8.2 华人

8.3 馬來人

8.4 馬蘭諾人

8.5 比达友族

8.6 烏魯人

8.7 宗教信仰

8.8 語言

9 文化

9.1 藝術及手工藝品

9.2 飲食

9.3 媒體

9.4 假日及節慶

9.5 体育

10 知名人物

11 参看

12 注释

13 参考来源

14 外部連結

词源

根据官方解释,“砂拉越”(Sarawak)一词来自砂拉越马来语中“锑”一词(serawak)。同时,民间也存在着非官方但有一定知名度的解释,即据称在1841年汶莱苏丹的舅舅班根丁·木达·哈新(Pangeran Muda Hashim)将砂拉越让给詹姆斯·布鲁克时,曾说道“我把它交给你了”(Saya serah pada awak),于是这块土地便由这句话中四个马来语词的缩写而命名[23]。不過上述說法有許多不合理之處,砂拉越這個名字早在布鲁克到砂拉越之前就已經存在,而「awak」這個字是在馬來西亞成立後,才開始出現在砂拉越马来语中[24]。

馬來西亞華語規範理事會在2004年成立後,中文譯名由原來的“砂𦛨越”統一為“砂拉越”,至此马来西亚全国的教科书、传媒等皆使用“砂拉越”作为本州之中文译名[25][26]。

歷史

史前

尼亞洞入口

距今四万年前,婆羅洲仍與東南亞大陸連接時,首批覓食者開始在尼亞洞的西口定居[27]。當時尼亞洞的地形比現在乾燥和顯露。史前時期,尼亞洞被灌木、綠地、沼澤、河流所組成的茂密森林所包圍,而居於尼亞洞的覓食者以打獵、捕魚、飼養软体动物和種植食用植物為生[28]。1958年,湯姆·哈里森在尼亞洞的深海溝發現暱稱為「深頭骨」(Deep Skull)的現代人類頭骨,證明了這個觀點[27][29]。「深頭骨」亦是東南亞最古老的现代人類頭骨[30]。該頭骨可能屬於一個年齡介乎16至17歲的少女[28]。此外,一具公元前三万年的穿山甲骸骨亦在尼亞洞附近被發現[31],另外,尼亞洞內亦發現中石器時代和新石器时代的墓葬遗址[32]。尼亞洞周圍的地區其後被劃作國家公園[33]。

其他考古遗址分佈於砂拉越的中部和南部。1949年,哈里森在山都望山(今古晋附近)發現唐宋年間的中国陶瓷,以此推斷山都望山直至元明時期可能都是砂拉越的一個主要港口[34][35]。砂拉越的考古遗址還包括加帛、桑、西连和石隆門[36]。

汶莱帝國

一幅描绘砂拉越河沿岸景色的19世纪画作,來自倫敦國家航海博物館

在16世紀,砂拉越的古晉地带[37]被葡萄牙地图学者称为「Cerava」[18],是婆羅洲島上的五大港口之一。[38]当时砂拉越位處汶萊帝國的势力范围,由蘇丹登加管理。[14]19世紀初,汶萊蘇丹逐渐失去對砂拉越的控制[18],只能管轄砂拉越的沿海地带,這些地區由半獨立的马来族领袖管理;内陸地區则由伊班族、卡扬族、和肯雅族的部落戰爭所主导,这些族群積極擴張他們的領土。[39]在古晉地區發現銻礦后,班根丁·馬哥達(Pangeran Indera Mahkota,汶萊蘇丹的代表)自1824年至1830年開始建设该地区。随着锑矿產量的逐年增加,汶萊蘇丹亦在当地不断增加税收[40],導致砂拉越社會出现動盪和混乱[18]。1839年,汶萊苏丹奥马尔·阿里·赛义夫丁二世指派班根丁·木达·哈新(汶萊苏丹的舅舅)派兵恢復秩序。此时英国探险家詹姆斯·布魯克到達砂拉越。[18]班根丁·木达·哈新要求布鲁克援助维稳,但布魯克拒絕了他的请求[18]。随后哈新二度接触布鲁克,布氏最终同意了哈新的請求。1841年,木达·哈新簽署條約将砂拉越割让给布魯克。1841年9月24日,[41]木达·哈新任布鲁克为砂拉越州長。1846年,木达·哈新去世,布魯克成為砂拉越的唯一统治者,建立白人拉惹王朝。[42][43]

布鲁克王朝

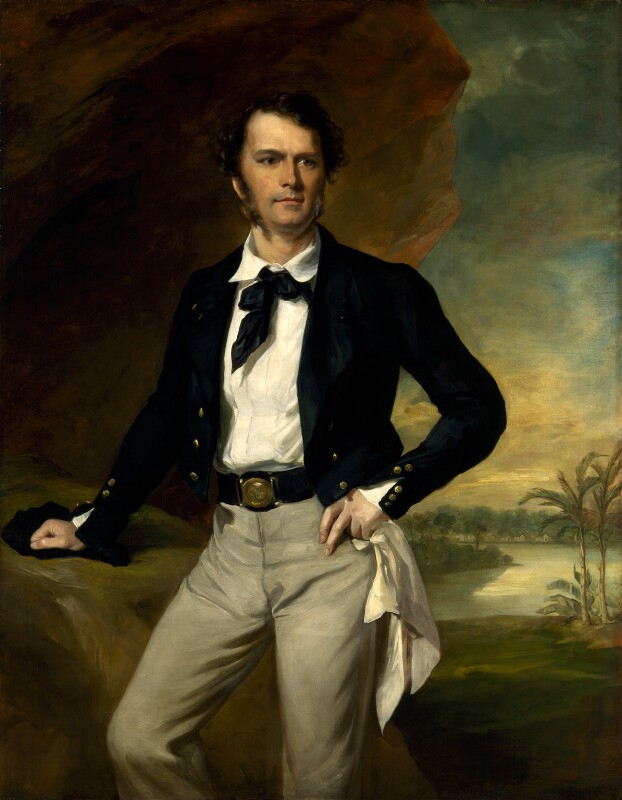

砂拉越首任拉惹詹姆斯·布魯克爵士

詹姆斯·布魯克統治砂拉越後,砂拉越的領土向北擴張。1868年,詹姆斯逝世,由其姪子查尔斯·安东尼·约翰逊·布鲁克繼位,其後再由其子查尔斯·怀纳·布鲁克繼位,並由其弟伯特伦·布鲁克輔政[44]。詹姆斯和查爾斯均與汶萊簽約,作為擴張砂拉越領土的策略。1861年,汶萊割讓民都鲁給詹姆斯,其後在1883年,砂拉越的領土擴張至峇南河一帶。1885年,布鲁克家族又購入林夢一帶的土地,並在1890年將其納入砂拉越的版圖。砂拉越的擴張活動直至1905年汶萊割讓老越給砂拉越後方告終止[45][46]。砂拉越當時設有5個省份,其邊界對應了布鲁克家族多年來的土地收購順序,而各省由一名參政司領導[47]。1850年,砂拉越被美國承認為獨立國家,其後英國亦在1864年承認。砂拉越在1858年發行其法定貨幣砂拉越元[48]。但是,在馬來西亞史觀上,布魯克家族被視為殖民主義者[49]。

1888年的砂拉越郵票,印有時任拉惹查爾斯·布魯克的照片

布鲁克王朝以「白人拉惹」的身份統治砂拉越一百年[50]。在布鲁克王朝統治下,砂拉越政府採納爱国主义政策,以保障土著權益和福利。砂拉越政府成立了由馬來人為首的最高委員會,對政府的決策提出建議[51]。最高委員會的首次會議於1867年在民都鲁舉行。最高委員會亦成為了馬來西亞歷史最悠久的立法機關[52]。同時,伊班族人和達雅族人亦被聘用作民兵[53]。布魯克王朝亦鼓勵華商移民到砂拉越以協助砂拉越的經濟發展,尤其是在發展矿业和农业方面[51]。當時,西方資本家被限制進入砂拉越,但砂拉越政府亦容許基督教傳教士到砂拉越傳教[51]。 當時的砂拉越政府亦禁止海盗、奴隶制度和猎首[54]。1856年,婆羅洲有限公司成立,並在砂拉越從事各种业务,包括貿易、銀行、農業、採擴及發展等行業[55]。

詹姆斯·布魯克原本居於古晉的一家馬來風格的屋子內。1857年,以刘善邦為首的石隆门客家華人淘金者破壞布魯克的居所。詹姆斯逃離後,與查尔斯[56]和其馬來族和伊班族支持者召集一支規模更大的軍隊[51]。幾天後,布魯克的軍隊成功截斷華人叛軍的逃走路線,並在2個月後殲滅叛軍[57]。布魯克家族其後在古晉砂拉越河畔建立新居所,亦即現今的阿斯塔纳皇宫[58][59]。汶萊皇室的反布魯克王朝派系亦在1860年在木膠被打敗。其他被布魯克家族打敗的知名反抗者包括伊班族領袖仁答和馬來族領袖沙里夫·马沙荷[51]。因此,砂拉越政府在古晉周圍興建炮台,以巩固拉惹的權力,其中便包括1879年建成的玛格烈达堡[59]。1891年,查尔斯·安东尼·布鲁克成立婆羅洲歷史最悠久的博物館砂拉越博物馆[59][60]。

1941年布魯克王朝統治砂拉越100周年之際,限制拉惹權力和讓砂拉越人民在政府運作上扮演更大角色的《1941年砂拉越憲法》制訂[61]。但是,草擬的憲法包含了违规行为,包括查尔斯·怀纳·布鲁克和英國政府官員之間的秘密協議,該秘密協議訂明怀纳·布鲁克將砂拉越割讓給英國成為直轄殖民地,而英國則給予怀纳·布鲁克及其家庭经济补偿[50][62]。

日本军事占领及盟军收复

巴都林当战俘营的航拍照片,摄于1945年8月29日(或晚于此)

第二次世界大战时期,查尔斯·维纳·布鲁克统治的布鲁克王朝于域内进行了备战部署,于古晋、乌驿、木胶、民都鲁和美里建设了简易的跑道机场。1941年,英军主力驻军撤出砂拉越,被调往新加坡,砂拉越地区基本无军防备。因此,布鲁克政权制定了焦土政策的防御方针,计划在美里失守时炸毁当地的油田,若在古晋沦陷,则将当地机场炸毁。日军参战后南下进占北婆三邦,以保护马来亚战役的日军侧翼,并计划以此为踏板,进占荷属东印度的苏门答腊和西爪哇。马来亚战役爆发8日后的1941年12月16日,川口清健率军于美里登陆,于24日征服古晋,守军指挥官C·M·莱恩中校撤退至荷属婆罗洲的边境城市山口洋市。1942年4月1日,在10周的战斗过后,盟军守军决定投降[63][64]。而在日军开始入侵砂拉越时,查尔斯·维纳·布鲁克便已逃亡至澳大利亚的悉尼;其下属官员多为日军所俘虏,被押送至巴都林当战俘营[65]。

1945年9月11日,日军军官于古晋向澳大利亚士兵投降

日本共统治砂拉越3年8个月。砂拉越、北婆罗洲和文莱一并被日本划入北婆罗地区(日語:北ボルネオ)[66],由日本陆军第37軍负责防御,驻地设于古晋(日本称久镇)。日本将英国殖民政府的省制区划废除,分为久镇州、美里州、志布州三个州划,各州由州长官治理。但日本并未完全废除英国殖民政府的行政架构,只是将新任日籍官员派驻进入旧政府,替代原英籍官员。内陆地区则多交予当地警员和村长管理,由日方监督。当地的马来人大抵接受日本的统治权,亦有部分土著部族因政府之义务劳动、食品征收、枪支没收等差别政策主张反抗,包括伊班族、卡扬族、肯亚族、加拉畢族和伦巴旺族等。但日本占领砂拉越后,许多华人自城区迁往内地,避免与日本人打交道。对于华人,日本采取趋于放任的态度,因当地华人大多不关心政事[67]。

1942年6月,盟军设立Z特种部队以破坏日军于东南亚的军事行动进程。而盟军的规模性反攻直至1945年才正式开始进行。当年3月,Z特种部队发起螞蟻行动[68],将军事将领空投至婆罗洲丛林,于砂拉越建立起数个军事行动据点。盟军亦于当地训练有数百名原住民军人,以期发动对日反攻。螞蟻行动据点为以澳军为首的盟军部队提供了有力的军事情报,1945年5月,盟军发动双簧管六号行动顺利攻占婆罗洲大部分领土[69],9月10日,日军于纳闽向澳军投降[70][71],并在翌日在停泊于古晋的澳军卡潘达号护卫舰的甲板上举行了受降仪式[72]。而英国在重归砂拉越后临时划其为軍事管制區,至1946年4月重新建立起殖民体系[73]。

英属直轄殖民地

1946年,布鲁克家族决定将砂拉越交给英王直接管辖。为此,一些砂拉越民众走上街头进行抗议

战争结束后,布鲁克政权回归砂拉越,但布政权没有足够资源重建砂拉越。而布鲁克家族内部,也面临继承争端——由于二人之间的政治隔阂,查尔斯·维纳·布鲁克亦不愿将权力交付给侄子安东尼[39];维纳之妻西尔维娅·布蕾特亦试图破坏安东尼的名声,以便令自己的女儿获得继承权。最终维纳·布鲁克决定将砂拉越的治权交回至英王,成立直辖殖民地[62]。随后经过内格里会议(今砂州立法议会)持续三日的讨论,1946年5月17日,让渡法案以19票支持比16票反对的微弱优势,正式通过。其中支持让渡者大多为欧裔官员,反对者大多为马来族官员。[來源請求]让渡法案的通过也在砂拉越民间引发起一阵风波,上百名马来族官员走上街头进行示威,而后续的反让渡浪潮持续数年,史称砂拉越反让渡运动[74]。在此期间的1949年12月3日,时任英属砂拉越总督邓肯·斯图尔特爵士更是遭到了当地民族主义者羅斯里多比的刺杀[75][76]。

安东尼·布鲁克是让渡的反对者,被传与反让渡组织有所联系,尤其是在邓肯·斯图尔特爵士遇刺后[77]。虽然砂拉越在1946年7月1日已正式成为英属直辖殖民地,但是安东尼·布鲁克仍宣称自己作为砂拉越王公,对砂拉越拥有治权[62],因此他被殖民当局逐出砂拉越[51],直至17年后才得以复归访问,而当时砂拉越已经是新独立的马来西亚的一部分[78]。1950年,殖民政府加大力度镇压反让渡运动,得以基本平息乱局[39]。1951年,安东尼·布鲁克于英國樞密院采取的法律行动亦宣告失败,最终安东尼只得放弃其对于砂拉越治权的全部要求[78]。

自治和馬來西亞

第一任砂州首长史蒂芬·甘隆宁甘于1963年9月16日宣布馬來西亞成立

1961年5月27日,马来亚联合邦首相東姑阿都拉曼提出联合計劃,希望将新加坡、砂拉越、沙巴和文莱结合为统一的联邦国家馬來西亞。由于馬來亞联合邦和婆羅洲之間社會經濟發展的巨大差距,該計劃引起了砂拉越当局的警惕。随后砂拉越政界更是出现了普遍的担忧,认为如果不形成统一的政治联盟,婆洲州属都將变相沦为馬來亞的殖民地。因此砂拉越出现了数个政黨,以维护他們所代表的群體的利益。[79]

1962年1月17日,科博爾德委員會成立,以调查砂拉越和沙巴對于联合邦计划的支持度。1962年2月至4月期間,該委員會调查了4,000多人,并收到了來自各團體的2,200份備忘錄,委員會報告显示婆洲居民对于联合议题存在分歧[80] 根据委員會報告,80%砂拉越人民支持共组马来西亚,唯前提是要报章砂拉越以及砂拉越各民族和宗教人群。[80][81]砂拉越起草《十八点协议》以維護它在聯邦裡的地位。1962年9月26日,砂拉越州议会通過了支持成立馬來西亞的決議,但前提是砂拉越人民的利益不會受到損害。1962年10月23日,砂拉越五個政黨結成統一陣線以支持成立馬來西亞[79]。

1963年7月22日, 砂拉越被賦予自治权[15][16][17],1963年9月16日,砂拉越与馬來亞联合邦、北婆羅洲和新加坡共同组成馬來西亞。[82][83]

1965年,砂拉越突擊隊乘坐澳大利亚皇家空军UH-1直升機守衛受共產黨潜袭威脅的马泰边界

馬來西亞引起了菲律賓、印尼、汶莱人民黨和砂拉越共产党的反對。菲律賓和印尼宣稱,英國將会通过馬來西亞以新殖民主义的方式来统治婆羅洲的州属。[84]同时,汶莱人民党主席阿查哈里于1962年12月策動汶莱起義反对文萊加入馬來西亞[85]。阿查哈里占领了砂州的林夢(Limbang)和柏戈奴,但最终被來自新加坡的英國軍隊擊敗。印尼总统蘇卡諾聲稱汶萊起義是民众反對馬來西亞的確鑿證據,并决定进攻馬來西亞。最初印尼派遣武裝志願军進入砂拉越,後來则直接派軍干涉。1962至1966年,砂拉越成为印马對抗的最前线。[86][87]除了砂共产党以外,砂拉越人民多数不支持馬印兩國之間的對峙。數以千計的砂共成員進入加里曼丹接受印度尼西亞共產黨的培訓。馬印對抗期間,約由10,000至150,000人組成的英國軍隊駐紮在砂拉越,此外亦有澳大利亞和紐西蘭部隊驻扎于砂拉越。蘇哈托成为印尼总统后,馬來西亞和印尼重启談判。1966年8月11日,马印冲突結束。1967年,双方签署了新協議:任何通過砂拉越-加里曼丹邊境的人士,需要持有邊境管制站的许可通行證才可通过。[84]

1949年,中华人民共和国成立,毛泽东思想開始滲透到砂拉越华人學校。砂拉越的第一個共產主義組织於1951年在古晉中華中學成立。1954年,該組织改组为砂拉越解放同盟(解盟),亦即砂共,活跃于各學校、工會和農村之中。[88][89]砂共主要在砂州的南部和中部地區集中活动,文铭权和黄紀作是砂共的兩位主要領導者。砂共亦成功滲透砂拉越人民联合党,試圖通過憲法建立社会主义國家。在马印對抗時期,砂共开始反政府武裝鬥爭[39]。此後,砂拉越政府開始沿古晉-西連道路建立新村,以防止公眾幫助共產黨。1970年,砂共改组为北加里曼丹共产党(北加共)。1973年,黃紀作向首席部長阿都拉曼耶谷投降,共產黨实力大损。而自1960年代開始在中國領導砂共的文铭权则主张持續与政府对抗。1974年後,砂共在拉讓江繼續进行武裝鬥爭。1989年,馬來亞共產黨(馬共)與大馬政府簽署了和平協議,其後北加共也随之重新與砂政府談判,並於1990年10月17日簽署斯里阿曼和平協議(Peace Declaration of Sri Aman)。共产党余部随后相继投降,最後一批約50人的北加共游擊隊投降后,砂拉越回復和平[90][91][92]。

2017年为石隆门华工起义160周年,1989年获砂拉越政府平反[93]。

政治

政府

砂拉越政黨54年的演变

砂拉越州元首(馬來語:Yang di-Pertua Negeri,可简称为“TYT”或“总督”)。该职位和其他马来西亚州的苏丹/拉惹拥有一样的地位,即作为州内土著习俗和伊斯兰的统治者。该职位由马来西亚最高元首委任,[94] 而州元首拥有权力委任首席部长成为砂拉越的政府首脑,现任砂拉越州元首为泰益玛目。拥有大多數州立法議员支持的政黨領袖将被任命為首席部長。每位民選州立法議會代表被稱為州議員,目前一共有82名。砂拉越州議會负责通過州内的法律,如土地管理、就業、森林、移民、商業航運和漁業。砂拉越州内阁是由首席部長、內閣部長和助理部長所组成的。[95]

為了保障砂拉越参组馬來西亞的权益,馬來西亞憲法内有列出特别保障措施,其中包括砂拉越政府可以限制西马和沙巴居民的入境居留的權力。另外,只有砂拉越州出生的律師可以在当地從事法律工作。砂拉越的高等法庭和西马高等法庭也享有平等的地位。砂拉越高庭首席法官任命之前必須与砂州首長進行協商。

砂拉越也有自身的土著法院,并可從聯邦政府那里獲得特別津貼。砂拉越土著可享有特權,如公共服務、獎學金、大學申请、就業和營業許可證的配額。[96] 除此之外,砂拉越州政府辖下的地方政府不受马来西亚国會所頒布的地方政府法令约束。[97]

坐落于砂拉越河旁的砂拉越立法議會大厦。

砂拉越主要政黨可以分為三大類,即非穆斯林土著、穆斯林土著和非土著政黨。但是大部分的政党成员由多个族群组成。[98]目前砂拉越州立法议会由砂拉越政党联盟(GPS)占多数,而来自砂土保党阿邦佐哈里是现任州首长。现为中央政府执政联盟的希望联盟也在砂拉越州议会拥有若干席位,反对党领袖则由现任马来西亚国内贸易及消费人事务部副部长,来自民主行动党的张健仁出任[來源請求]。

于1959年成立的砂拉越人民联合党(人联党,SUPP)是砂拉越第一個政黨。其他早期政党还有砂拉越国家党(PANAS,1960年成立)、砂国民党(SNAP,1961年成立)和砂保守党(PESAKA,1962年成立)[39]。自1963年馬來西亞成立以来,砂拉越一直是当时的執政黨联盟以及联盟的扩充版-國陣的大本營。1963年,来自砂国民党的史蒂芬·甘隆宁甘在議會選舉获得壓倒性勝利后,成为砂拉越首任首席部长。但是史蒂芬任职3年至1966年后便被砂保守党的達威斯里在中央政府的协助下拉下台,引发1966年砂拉越憲法危機。[39]在这之后,砂州政治局面趋向穩定,直至1987年明阁事件。这起政變是由時任首席部長泰益瑪目的舅舅所發起的,目的是为了推翻以泰益為首的國陣;但最终政變失敗,泰益继续成为该州的首席部長。[99]

@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinner{width:100%!important;max-width:none!important}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center}}

泰益瑪目是现任州元首。

1970年是砂拉越参组马来西亚后的第一届州選舉。砂拉越州立法議會成員有選民直選,并標誌著馬蘭諾民族领袖如阿都拉曼耶谷和泰益瑪目领导砂拉越政治。同年,北加里曼丹共產黨(北加共,NKCP)成立,并开始对新當選的砂州政府进行游擊戰。该黨于1990年签署和平協議後便宣告解散。[92]1973年,砂拉越土著保守党由土著党和保守党合并。[100]這個政黨後來成為砂拉越國陣的中堅力量。相反的,自1983年以來,由達雅族组成的砂国民党因领导危机而分裂成若干小政黨。[101][102]砂拉越州选最初是與全國選舉同步举行的。然而在1978年,當時的首席部長阿都拉曼耶谷决定延遲州选一年,以做好準備面对新成立的反對黨挑戰和需要更多时间来解决砂国民党加入砂州國陣后的议席分配。[103]自此以后,砂拉越成为馬來西亞目前唯一不和全国国会和州议会选举同步举行的州属。[104]

1978年,原为西马政党的民主行动党(DAP)开始于砂拉越设立支部[100]。自2006年州選舉後,该黨获得多數城市华裔选民的支持,成為目前砂拉越最大反對黨。[105]2010年,它与人民公正黨(PKR)和马来西亚伊斯兰党(PAS)成立了民联。後兩黨在1996年和2001年之間才开始活躍于砂拉越政坛。[106] 砂拉越在2018年大选前是馬來西亞唯一一个没有国阵西马成员党的州属,其中该政治联盟内最大的政党巫統也不在当地参选。[107]随着2018年马来西亚大选举行后,由民主行动党、人民公正党、国家诚信党和土著团结党组成的希望联盟成功获得多数国会席位,并在砂拉越国会席位中从原有的6个增加至13个[來源請求]。为了应付预计于2021年举行的砂拉越州选举,砂拉越的四个国阵成员党在大选后一齐退出国阵,成立砂拉越政党联盟取而代之,使砂拉越成为唯一一个没有国阵议员的马来西亚州属[來源請求]。

行政区划

省份

和马来西亚半岛其他州属不同的是,砂拉越州以下的第一級行政區是省(Bahagian),而不是縣(Daerah)。每個省都由省长领导。截至2018年,砂拉越州内一共有12個省[94][108]:

林梦省

美里省

民都鲁省

加帛省

诗巫省

沐膠省

泗里街省

木中省

诗里阿曼省

三马拉汉省

古晋省

西连省

砂拉越州省份 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 大区 | 中文省名 | 马来文省名 | 省会 | 人口(2010年[109]) | 地方政府 | 面积(平方公里) |

中砂 | 木中省 | Bahagian Betong | 木中 | 108,225 | 木中县议会、实拉卓县议会 | 4,180.8 |

| 中砂 | 民都鲁省 | Bahagian Bintulu | 民都鲁 | 219,529 | 民都鲁省发展局 | 12,166.2 |

| 中砂 | 加帛省 | Bahagian Kapit | 加帛 | 112,762 | 加帛区议会、桑坡县议会、巫拉甲县议会 | 38,934 |

西砂 | 古晋省 | Bahagian Kuching | 古晋 | 705,546 | 古晋南市市政厅、古晋北市市政局、巴达旺市议会、石隆门县议会、伦乐县议会 | 4,565.53 |

北砂 | 林梦省 | Bahagian Limbang | 林梦 | 86,571 | 林梦县议会、老越县议会 | 7,790 |

| 北砂 | 美里省 | Bahagian Miri | 美里 | 364,562 | 美里市政厅、马鲁帝县议会、苏必县议会 | 26,777 |

| 中砂 | 沐胶省 | Bahagian Mukah | 沐胶 | 106,931 | 拉叻沐胶县议会、玛都达佬县议会 | 6,997.61 |

| 西砂 | 三马拉汉省 | Bahagian Samarahan | 哥打三马拉汉 | 155,183 | 三马拉汉市议会、实文然县议会 | 2,927.5 |

| 中砂 | 泗里街省 | Bahagian Sarikei | 泗里街 | 145,200 | 泗里街县议会、马拉端芦楼县议会、巴干县议会 | 4,332.4 |

| 西砂 | 西连省 | Bahagian Serian | 西连 | 91,599(不包括新生村副县) | 西连县议会 | 2,039.9(不包括新生村副县) |

| 中砂 | 诗巫省 | Bahagian Sibu | 诗巫 | 299,768 | 诗巫市议会、诗巫乡区县议会、加拿逸县议会 | 8,278.3 |

| 西砂 | 诗里阿曼省 | Bahagian Sri Aman | 诗里阿曼 | 94,774 | 诗里阿曼县议会、鲁勃安都县议会 | 5,466.25 |

縣

省以下分為由縣長領導的縣,縣以下又分為由砂拉越行政官(Sarawak Administrative Officer, SAO)領導的副县。截至2015年,整個州一共分為39個縣。砂州各省、縣都設有發展官一職(Development Officer),發展官的職責是推行轄區的發展項目。砂州各省每一條村的村長(稱為ketua kampung或penghulu)都會由州政府任命[94][108]。砂拉越州39個地方政府都處於砂拉越地方政府與社區發展部的管轄之下[110]。砂拉越州各省、縣、副縣的列表如下[7]:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

保安

砂拉越第一支準軍事武裝部隊是由布魯克王朝在1862年建立的兵團,稱為砂拉越突擊隊[111]。這支兵團曾經協助布魯克家族平定砂拉越王國,並參加對日軍的游擊戰,以及在馬來亞緊急狀態和砂拉越共產黨叛亂期間對共產黨的游擊戰。這支以叢林跟蹤技能聞名的軍團在馬來西亞成立之後便併入馬來西亞軍隊,成為皇家遊騎兵團[112]。砂拉越在1888年和毗鄰的北婆羅洲、汶萊一起成為英國的保护国,自此砂拉越便把外交事務交由英國負責,以換取英國的軍事保護[113]。砂拉越的安保工作也曾經是澳大利亚和新西兰的責任[114]。馬來西亞成立後,該國的外交政策和軍隊事務便由馬來西亞聯邦政府全權負責[115][116]。

领土争端

砂拉越和邻邦文莱、印尼以及在南海岛屿主权上与中国等多个国家有着领土争端[117][118]。砂拉越在2009年解決了與汶萊之間關於林夢省的主權爭議,最後汶萊放棄了對這片土地的主權要求[119]。砂拉越主張曾母暗沙(Beting Serupai)和的北康暗沙(Beting Raja Jarum/Patinggi Ali)是其专属经济区的一部分[120],另外幾項關於砂拉越-加里曼丹邊界的問題也尚未與印尼解決[121]。

環境

地理

從美国国家航空航天局衛星影像可見砂拉越位在婆羅洲西北部。

砂拉越的陸地總面積近124,450平方公里,佔馬來西亞總面積的37.5%,坐落在北緯0度50分至5度、東經109度36分至115度40分之間[122]。此州擁有一大片具有豐富動植物物種的热带雨林[18]。

砂拉越州的海岸線長達750公里(470英里),其中北部海岸線隔斷著約有150公里的汶萊海岸線。砂拉越和加里曼丹之间由婆羅洲的中央山脈隔开。這些山脉在北部更加高耸,而最高的陡峭则位于巴南河的源頭附近,即巴杜拉威山和姆鲁山。毛律山為砂拉越最高峰[18]。兰卑尔山国家公园则以各種形式的瀑布聞名[123]。位在姆鲁山国家公园的砂拉越洞厅為世界最大的地下洞穴大廳。該國家公園內的其他景點也包含了鹿洞,也是世界最大的洞穴通道[124]以及拥有东南亚最大的洞穴系統的清水洞[125][126]。該國家公園也是联合国教育、科学及文化组织所評定的世界遗产[127]。

砂拉越一般上被分為三個生態區。其中沿海地带的地勢平坦,并由沼澤和潮濕環境以及平原组成。砂拉越海灘包括位于古晋的巴西班让海滩(Pasir Panjang)[128]和达迈海滩(Damai Beach)、[129]民都鲁的丹绒巴都海滩(Tanjung Batu Beach)[130]和丹绒罗邦公园(Tanjung Lobang)[131]和美里的夏威夷沙滩。[132] 其中多數市鎮都坐落于沿海地带或是河流旁,如古晋(砂拉越河)和詩巫(拉让江)的港口便是建立在河流旁,距离海岸有一段距離。民都魯和美里坐落于海岸線旁,面向南中国海。第三个區域是靠近着加里曼丹北方的高山地带。其中包括位于加拉畢高原的巴里奥、姆鲁高原(Murut Highlands)的巴卡拉兰和位于肯雅高原(Kenyah Highlands)的乌山阿包。[18]

拉让江為馬來西亞最長的河流

砂拉越境內的主要河流有砂拉越河、魯巴河(Batang Lupar)、沙里巴斯河(Sungai Saribas)以及拉让江等。砂拉越河為流經古晉省的主要河流。拉让江為馬來西亞最長的河流,其長度加上其支流巴类河共約563公里。巴南河、林夢河以及大老山河(Sungai Trusan)皆注入於汶萊灣[18]。

砂拉越属于熱帶雨林氣候,并有東北季風和西南季風兩個季风季節。東北季風在十一月和二月之間出現,并带来了大量降雨量,而西南季風的降雨量較少。除了這兩個季風,砂拉越的全年氣候穩定。每日平均溫差大致上是從早上的23 °C(73 °F)到下午的32 °C(90 °F)。美里相較於砂拉越其他主要城市,拥有比较低的平均氣溫。美里還擁有最久的日照(每天超過6個小時),而其他地區则收到了一天五六個小時的日照。砂拉越濕度通常較高,大约为68%,年降雨量则处于330厘米(130英寸)和460厘米(180英寸)之間,一年有220天降雨。[122]石質土構成砂拉越60%的土地,灰化土则佔土地面積的12%。沖積層可在沿海和河岸地區找到,而泥炭沼澤森林覆蓋了砂拉越土地面積的12%。[122]

砂拉越可分成兩种地質,第一种地质是巽他板塊,从魯巴河发源(靠近詩里阿曼)并往西南延伸,形成砂拉越的西南端。还有一个是地槽區域,是从魯巴河往東北延伸,形成砂拉越的中部和北部地區。砂拉越南端最古老的岩石是片岩,是在石炭纪和二叠纪时形成的。而這個區域最年輕的火成岩是安山岩,主要位于古晋省的三马丹。砂拉越中部和北部地質是在晚期的白垩纪才开始形成,可找到的石頭類型有页岩、砂岩和燧石。[122]

- 砂拉越境內的地標

姆鲁山国家公园境內的尖峰石阵

砂拉越境內的叢林

峇哥国家公园

從砂拉越觀望南中国海

生物多樣性

在馬來西亞砂拉越州尼亞洞里的灰鶲(Muscicapa dauurica)。

红树林和水椰林覆蓋著砂拉越的海岸線。 它形成砂拉越森林總面積的百分之二,在最常見古晉、泗裡街、和林夢的河口。在這裡可找到的樹木主要包括:巴哥(红树属)、尼帕棕榈(水椰)和尼红树(Oncosperma tigillarium)。 涵蓋了砂州林地16%泥炭沼澤森林主要集中在美裡南部和巴南谷。 在泥炭沼澤森林的主要樹種有: 拉敏白木、梅兰蒂(娑羅屬種類)和絨廣木(Dactylocladus stenostachys)。巽他荒原森林佔森林總面積的百分之五,而龙脑香科树林佔據山區。[122]一些植物已用来研究它們的藥性。[133]

一只螞蟻從萊佛士豬籠草中飲蜜。

世界范围内的一高密度物種的雨林也生长在砂拉越境内。 該州有大約185種哺乳動物、530種鳥類、166種蛇、104種蜥蜴和113種兩棲動物。砂州還有19%的哺乳動物、6%的鳥、20%的蛇和32%的蜥蜴的特有物種。這些物種可在保護區中找到。砂拉越还有2000種樹種、1000種蘭花、757種蕨類植物和260種棕櫚。[134]該州也是瀕危動物的棲息地,其中包括婆罗洲象、長鼻猴、 婆羅洲猩猩、和犀牛。[135][136][137][138][139]马当野生动物中心(Matang Wildlife Centre,位于库巴国家公园)、 实蒙古野生动物护育中心(Semenggoh Nature Reserve)、和兰扎恩地茂野生保护区[140]著名于他們的猩猩保護計劃。[141][142]达郎沙当国家公园(Talang-Satang National Park)著名于它的海龜保護措施。[143]观鸟活動可在不同的國家公園里进行,如姆魯山國家公園、蘭卑爾山國家公園、[144]和西米拉遥国家公园。[145]美里-实务地珊瑚礁国家公園著名于它的珊瑚礁、[146]和加丁山國家公園(Gunung Gading National Park)著名于它的萊佛士花。[147]峇哥国家公园,是砂拉越最古老的國家公園。它以其275種長鼻猴著称。[148]另一方面,巴达旺豬籠草花園(Padawan Pitcher Plant & Wild Orchid Centre)為它的各種肉食豬籠草著称。[149]馬來犀鳥是砂拉越的州鳥。[150]

砂拉越州政府頒布了若干法律,以保護森林和瀕危野生物種,其中包括1958年森林條例、[151]1998年野生動物保護條例[152]和砂拉越自然公園和自然保護區條例。[153]受保護的物種有猩猩、綠海龜、飛狐猴、和管道犀鳥。根據1998年野生動物保護條例,砂拉越原住民被賦予權限來獵取有限的野生動物,但不應該擁有超過5公斤(11英磅)的肉。[154]砂拉越森林部成立於1919年,以保護其森林資源。[155]繼砂拉越伐木業在國際社會受到批評,州政府決定縮減砂拉越森林部並於1995年創建砂拉越林業公司(SFC,Sarawak Forestry Corporation)。[156][157]砂拉越生物多樣性中心成立於1997年,為的是保存、保護、并维持生物多樣性的长期發展。[158]

环保课題

沿着拉讓江一带的伐木營地。

砂拉越目前的森林覆蓋率一直存在爭議。 當時的首席部長泰益瑪目聲稱,砂州在2011年拥有70%的森林覆蓋率,但是2012年却减至48%。[159]然而,在2012年他的內閣部長却聲稱,森林覆蓋率為80%。[159]砂州政府還計劃在未來幾年保持60%的森林覆蓋率。[160]砂拉越森林部門認為,2012年的森林覆蓋率为80%。[161]相比之下,國外媒體稱,砂拉越已經失去了90%的森林覆蓋率[162][163]只剩下3%到5%左右的森林。[164]根據濕地國際的研究报告,10%的砂拉越森林的和33%的泥炭沼澤森林在2005年至2010年間被清除,這是亞洲总伐木率的3.5倍和亞洲泥炭沼澤森林伐木率的11.7倍。[165][166]

伐木业和棕櫚油園的需求逐漸造成砂拉越雨林消耗殆盡。[167]当瑞士社運分子布鲁诺·曼瑟(Bruno Manser)從1984年到2000年進入砂拉越时,砂拉越本南族的人權和森林砍伐课題成為一個國際性的環境课題。[168]森林的砍伐影響了土著部落的生活,尤其是本南人。他们的生計非常依賴於森林產品。這導致了20世紀的80年代和90年代,土著族群开始封鎖通往他们部落的道路,以阻止伐木公司侵占他們的土地。[169]在一些情況下,土著習俗地在沒有當地人的許可下,被賦予伐木和種植公司。[170]土著已經使用法律途径,以恢復其土著習俗地的權利。2001年砂拉越高等法庭完全恢復了诺雅崴人的土著習俗地,不過,在2005年,上诉庭却推翻部分判决。但是,这项2001年的判决成为了先例,并隨後的幾年導致更多的土著習俗地的權利得到高級法庭的維護。[171][172]砂拉越大型水壩的政策,如巴贡水电站和姆伦水壩已淹沒數千公頃的森林并造成數千人土著居民流離失所。[173][174]自2013年起,巴南水壩項目已被展延因为當地土著部落正在進行水壩抗議活動。[175]自2014年以來,在新的首席部長丹斯里阿德南開始打擊非法伐木活動,并使砂州經濟多樣化。[176]在2016年,有超過200萬英畝的森林被列為保護區。这些保護區大多数是猩猩的棲息地[177]。

經濟

body.skin-minerva .mw-parser-output .transborder{border:solid transparent}

砂拉越各行業佔GDP份額(2013年)[178]

服務業 (37.2%)

製造業 (26.6%)

礦業及採石業 (21.5%)

農業 (11.4%)

建造業 (3.1%)

進口稅 (0.3%)

一座位於砂拉越民都魯的液化天然气港

砂拉越擁有豐富的自然資源。在2013年,採礦、農業、畜牧業等第一產業的產值佔全州經濟產量的32.8%[178]。砂拉越製造業產值的主要貢獻者是飲食業、木工業與藤器製造業、初级金属產品制造业和石油化工業[7],而服務業產值的主要貢獻者則包括貨運運輸業、航空業和旅遊業[178]。在2000年至2009年期間,砂拉越國內生產總值(GDP)的年均增長率是5.0%[179]。2006年至2013年期間當地GDP的年度增長率水平並不穩定,幅度由負2%(2009年)至7%(2010年)不等,標準差為3.3%。在2013年之前的九年內,砂拉越州的GDP總量對馬來西亞國內生產總值的贡献率為10.1%,是全國經濟總量第三大州,僅次於雪蘭莪(22.2%)和吉隆坡(13.9%)[178]。砂拉越的GDP已經從1963年的5.27億令吉(1.713億美元)增加到2013年的580億令吉(174億美元)[180],增幅達110倍。與此同時,當地的人均GDP也已經從1963年的688令吉躍升至2013年的46,000令吉,增幅達67倍[181]。砂拉越的人均GDP(44,437令吉,即11,133美元)在馬來西亞排名第三,僅次於吉隆坡和納閩[182]。油氣事業為砂拉越州政府貢獻了34.8%的稅收,因此州政府在2013年以前的7年內一直能夠維持財政盈餘。砂拉越還吸引了總值96億令吉(28.8億美元)的外國投資,其中90%的投資額都流向砂拉越再生能源走廊(Sarawak Corridor of Renewable Energy, SCORE);砂拉越再生能源走廊是馬來西亞第二大經濟走廊[178]。

砂拉越经济在很大程度上属于向外出口型,因此易受全球大宗商品價格所影响。砂州出口總額和砂州生產總值的比例為100%以上,而2013年,貿易總額超過了130%。 液化天然气 (LNG) 出口額佔砂州的總出口的一半以上;同時,原油出口佔20.8%。 與此同時,棕櫚油、原木、和木材佔出口總額的9.0%左右。[178] 砂拉越目前收到的5%的石油稅(礦業公司以石油產量的比例支付給贌的拥有者)是由馬來西亞國家石油公司在砂拉越水域勘探石油后所支付的。[183] 石油和天然氣的大部分都儲藏於民都魯和美裡離岸的地方、万年烟盆地、巴南盆地、和靠近北康暗沙岛屿。[184] 砂拉越也是世界上最大的硬木出口國之一,并在2000年佔馬來西亞總原木出口的65%。 2001年联合国估計砂拉越在1996至2000年之間,每年的平均原木出口是14,109,000立方米(498,300,000立方英尺)。[185] 1955年,華僑銀行是第一个在砂拉越开设分行的外国銀行。除了國內銀行,砂拉越也有18個歐洲銀行、10個中東銀行、11個亞洲銀行、和五個北美銀行在當地開設分行。[186] 砂拉越也有幾家本地公司涉及各项经济活动,如:砂州日光集团、常青集团、啟德行集團(KTS Group)、纳因控股公司(Naim Holdings)、三林(Samling)、升阳控股(Shin Yang)、大安集团(Ta Ann Holdings)和黃傳寬控股(WTK Holdings)[187]。

砂拉越消費者物價指數 (CPI) 與馬來西亞消費者物價指數有高度相關性。砂州從2009年至2013年間的平均通膨率是在2.5至3.0巴仙之间。但是2008年通膨率却高达10.0%,而在2009年却创下-4.0%的最低点。[178] 砂拉越收入不均从1980年至2009年並沒有出现顯著的變化,其基尼系数在0.4和0.5之間波動。[188][189] 砂拉越的貧窮率从1975年的56.5%減少至 2015年的1%。[190] 失业率也从2010年的4.6%[191]下滑至2014年的3%。[190]

能源

在巴贡水电站發電廠房裡面的涡轮发动机。该水壩是砂拉越主要的電能供应者。

砂能源公司 (SEB) 負責發電、輸電、以及分配電力到整個砂拉越。[192] 截至2015年,砂拉越有三個正在运作的水壩:峇丹艾、[193]巴贡水电站、[194] 和姆伦水壩。[195] 还有几个水壩在研究和規劃当中。[193] 砂拉越也从燃煤電廠和液化天然氣热力发电厂得到其電能。[192][196] 砂州發電總容量預計将在2025年達到7,000兆瓦。[197] 除了为本地居民供电,砂拉越能源公司還出口電力到鄰近的西加里曼丹省。[198] 替代能源如生物质、潮汐能、太陽能、風能和微水電站也被探索其潛在的發電用处。[199]

砂拉越再生能源走廊(SCORE)成立於2008年,並計劃至2030年進一步利用豐富的能源如:姆伦水壩、巴南水壩、巴类水壩(Baleh Dam)和燃煤電廠[200] 以及發展10项優先行業[201] 如鋁、玻璃、鋼鐵、石油、漁業、畜牧業、木材、和旅遊等等。[202] 區域走廊發展局(RECODA)負責管理砂拉越再生能源走廊。[203] 砂拉越再生能源走廊覆蓋整个砂拉越中區,包括三个主要地方:三馬拉如(靠近民都魯)、丹絨馬尼、和沐胶。[204] 自2008年,三馬拉如将被計劃開發成一個工業區,[205] 并把丹絨馬尼作為清真食品中心,[206]和把沐胶作為SCORE的行政中心,着重於資源研究和開發。[207]

旅游

法國吉普賽樂隊GYPSY IT UP在2006年熱帶雨林世界音樂節中演出

旅游业是砂拉越的重要经济产业。2015年,旅游业佔砂拉越州內生產總值的9.3%[208]。砂拉越旅遊局(Sarawak Tourism Board)是砂拉越旅遊部(Ministry of Tourism Sarawak)的下轄機構,負責推廣砂拉越旅遊。與此同時,砂拉越私營旅行社亦組成砂拉越旅遊聯合會(STF, Sarawak Tourism Federation)。砂勞越會議局(SCB, Sarawak Convention Bureau)則負責吸引大会、会议和企业活动前往古晉婆羅洲會議中心(BCCK)舉行相關活動[209]。砂拉越犀鸟旅游奖(RWMF, Rainforest World Music Festival)每兩年舉辦一次,以表揚最佳的旅遊業從業者[210]。

熱帶雨林世界音樂節(古晋)是砂拉越的國際音樂盛事,每年吸引超過2万人參加[211]。其他在砂拉越定期舉辦的盛事亦包括東盟國際電影節(古晋,AIFFA, ASEAN International Film Festival And Awards)、亞洲音樂節、婆羅洲爵士樂節(美里)、婆羅洲文化節(诗巫)和婆羅洲國際風箏節(民都鲁,BIKF, Borneo International Kite Festival)[209]、中秋嘉年华(民都鲁,Tanglung Carnival,2018年5天3万到访人次)[212]及新尧湾嘉年华(石隆门,Siniawan Heritage Fiesta,2017年2万到访人次)[213]。

砂拉越的主要商場包括位處古晉的新欣廣場(tHe Spring)、富丽华广场(Boulevard)、CityONE[214]、独立广场(Plaza Merdeka)和永旺(ÆON);位處美里的星城霸級廣場(Bintang Megamall)、富丽华广场(Boulevard)和帝宮城市廣場(Permaisuri Imperial City)[215];诗巫的三洋广场和大星广场(Star Megamall);民都鲁的百乐城(Paragon),以及民都鲁2019年即将建成的新欣廣場(tHe Spring)和富丽华广场(Boulevard)。砂拉越的首府古晉亦被評為馬來西亞其中一個退休目的地[216][217][218]。

砂拉越2017年访客达485.7万人次,主要来自汶萊(173.9万;2014年为195.2万,下同)、印尼(51.3万;54.7万)、菲律宾(6.8万;13.6万)、新加坡(4.2万;4.9万)、中国(3.8万;4.0万)及泰国(1.6万;未知)。[219][220][221][222]

| 重要旅游业指标 | 2010年 | 2011年 | 2012年 | 2013年 | 2014年 | 2015年 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 外国访客 (百万人) | 1.897 | 2.343 | 2.635 | 2.665 | 2.996 | 2.497 |

| 本国访客 (西马来西亚 & 沙巴) (百万人) | 1.373 | 1.452 | 1.434 | 1.707 | 1.862 | 2.020 |

| 访客总计(百万人) | 3.271 | 3.795 | 4.069 | 4.372 | 4.858 | 4.517 |

| 旅游业收入, 亿元 (林吉特) | 66.18 | 79.14 | 85.73 | 95.88 | 106.86 | 98.70 |

| 旅游业收入, 亿元 (等价美元) | 14.89 | 23.74 | 27.86 | 28.76 | 32.06 | N/A |

基础设施

相較於马来西亚半岛,砂拉越整體基礎設施的發展較為不足[224]。砂拉越基礎設施發展和通信部門(MIDCom)負責砂拉越的基礎設施及電信服務[225]。砂拉越有21個工業區,有四個主要機構負責其建設及發展[226]。2009年時,都市有94%有供應電力,鄉村供電比例從2009年的67%[227]成長到2014年的91%[228]。在電話上,2013年傳統固定式電話的覆蓋率為25.5%,而使用手機的人達到93.3%。同一年有使用電腦的比率為45.9%。都市有上網的人有58.5%,鄉村則有29.9%[229]。砂拉越州的Sacofa有限公司(Sacofa Sdn Bhd)全权負責架設砂拉越的通訊塔[230]。砂拉越資訊系統有限公司(Sarawak Information Systems Sdn Bhd,簡稱SAINS)負責砂拉越資訊科技系統(IT)的架設及發展[231]。2012年時,砂拉越有63個郵局、40個迷你郵局及5個流動郵務局[232]。2015年,鄉村的郵務覆蓋率為60%[233]。

古晉水务局(KWB)及詩巫水务局(SWB)負責相關區域的供水管理。LAKU管理有限公司(LAKU Management Sdn Bhd)负责管理美里、民都魯及林夢的供水[234]。鄉村供水部管理局则负责剩餘地區的供水[235]。2014年鄉村地區中有82%有自來水供應[228]。

交通

古晉國際機場航站楼

位于民都鲁港的民都鲁国际集装箱码头(BICT)

陆路

截至2013年 (2013-Missing required parameter 1=month!)[update],砂拉越拥有总长32,091公里(19,940英里)的道路,其中近半❲18,003公里(11,187英里)❳为州政府建設的铺设道路、8,313公里(5,165英里)为由林业公司建設的泥路、4,352公里(2,704英里)为碎石路、1,424公里(885英里)为联邦公路。砂拉越最重要的公路是泛婆大道,起自砂拉越州古晋省辖下三马丹,穿过汶莱,到达沙巴州的斗湖[236]。然而,砂拉越道路的路況因為危险的急弯、盲点、坑洞和路面侵蝕的问题而被批評[237],聯邦政府亦曾在財政預算中撥出資金用作改善砂拉越的道路。砂拉越作為再生能源走廊經濟地帶的一部份,亦興建了連接大型水電站、民都魯和加帛的道路[236]。

砂拉越的主要城鎮亦設有公共交通服務,包括巴士、的士及豪华轿车,現已有共享汽車Grab入駐,于古晉、美里、詩巫與民都魯四大城鎮及泗裡街提供服務。砂拉越亦設有前往沙巴、汶萊和印尼坤甸的巴士服務[234],目前古晉與民都魯已有冷氣長途巴士總站,而詩巫亦正建設中。砂拉越道路使用双车道設計,並靠左行駛[238]。砂拉越容許摩托車司機在出口沒有其他車輛的情況下轉左[239]。

空路

古晉國際機場是砂拉越的主要對外機場。美里機場亦有少量國際航班。其他規模較小機場如詩巫機場、民都魯機場、沐膠機場、馬魯帝機場、姆魯機場和林夢機場則提供往返吉隆坡和其他砂拉越城市的航線。砂拉越的一些鄉郊地區亦設有飞机跑道,主要聚集在北砂[236]。馬來西亞國際航空、亞洲航空和馬來西亞之翼航空提供往返砂拉越的航線[240]。由砂拉越政府持有的犀鸟航空則為州政府提供包機服務[241]。

繼馬來西亞國際航空、亞洲航空、酷航和快速航空開通古晉至外國的國際航線,鑒於快速航空(2013年)[242]及亞航(2017年)[243]先後運營古晉往來坤甸航線,印尼狮子航空也将坤甸至古晋与美里的新航线提上日程。[244]

古晋国际机场 | 美里机场 | |

|---|---|---|

亚洲航空(亚航)、马来西亚航空(马航)、 | 亚航、马航 | |

| 亚航、 | / | |

| 亚航[246] | / |

水路

砂拉越的主要港口位處古晉、詩巫、民都魯和美里[234]。其中民都魯港由馬來西亞聯邦政府直轄,亦是砂拉越最繁忙的港口,主要負責承運天然气产品和标准货物。其餘港口包括民都鲁省三马拉如工業港和木中省丹绒玛尼工业港。2013年,四大主要港口的吞吐量總和為6,104萬货运重量吨[236]。砂拉越擁有55個可通航的河流网络,其長度總和為3,300公里(2,100英里)。幾百年來,河流一直都是砂拉越主要的運輸途徑,亦是木材等农产品出口至馬來西亞主要港口的路線。距拉让江河口113公里(70英里)的詩巫港是拉让江的主要樞紐,主要用作付運木材。但是,由於丹绒玛尼工业港的建成,詩巫港的總吞吐量開始下跌[236]。快艇亦是砂拉越的主要水路交通工具[234]。

铁路

砂拉越由於后勤困难和人口分散的原因,並沒有建設鐵路[236];古晋轻快铁原定2019年开工及2024年完工(估计耗资110亿令吉),2018年9月砂州首长阿邦佐哈里宣称暂缓计划。该轻快铁共6条路线,首梯次将完成3条路线:[247][248][249]

- 1号线(达迈线):哥打三马拉汉(Kota Samarahan)经双溪峇都(Sungai Batu)至达迈(Damai)共28站62.4公里

- 2号线(西连线):西连(Serian)经实文然(Siburan)至史纳里(Senari)共26站82公里

- 3号线(古晋市中心线,电车):市区13站10.8公里

另三条路线为石隆门、德拉甲艾(Telaga Air)及外围连结路线。

医疗

砂拉越綜合醫院

砂拉越綜合醫院、詩巫醫院及美里醫院[250]是砂拉越的三个主要公立医院。除此之外也有一些县級醫院[251]、公共医疗診所、一个马来西亚診所(「一个马来西亚」計劃下的診所)以及鄉村診所[252]。除了公立的醫院及診所外,砂拉越也有一些私立的醫院,如古晉的婆羅洲醫療中心[253]

、Normah醫療中心、KPJ专科医院及Timberland醫療中心,詩巫的拉让醫療中心 [254]。砂拉越也是汶萊和印尼醫療旅行團的目的地[255]。马来西亚砂拉越大学(UNIMAS)是砂拉越唯一有醫學院的公立大學[252]。為了推廣類似居家環境的安寧病房服務,砂拉越安寧協會(Sarawak Hospice Society)在1998年成立[256]。聖淘沙醫院(Hospital Sentosa)是砂拉越唯一的精神病院[257]。

如何为鄉村地區提供有素质的醫療服務仍然是当地的一大挑戰[258]。針對一些不在診所醫療範圍內的村莊,會有隶属马来西亚飞行医生每個月一次的飛行醫療服務(FDS, Flying Doctors Service)。距離較遠的村子也會有醫療促進員,先接受三個星期的急救及基礎醫療訓練,之後就在村內駐點提供醫療。砂拉越的許多社群也仍在使用各種傳統的醫療方式[259][260][261][262][263]。

2015年時,砂拉越的醫生-居民比為1:1,104,較世界卫生组织建議的1:600的醫生-居民比要低。那年在砂拉越共有2,237名醫生,其中有1,759名在公立醫院,478名在私立醫院[264]。砂拉越還有248位專科醫師、942位正式醫師(medical officer)及499位實習醫師(house officer)[251]。

教育

馬來西亞砂拉越大學(UNIMAS)

砂拉越在1960年時的識字率為25%[265],現今的識字率已达90%。馬來西亞教育部負責砂拉越的小學教育及中學教育[266]。砂拉越最古老的學校是古晋圣多玛中学(1848)、古晉聖瑪麗中學(St Mary's School Kuching, 1848)及古晉聖約瑟中學(St Joseph's School Kuching, 1882,非2012年私立的古晉聖約瑟中學)[267]。2012年時砂拉越州内共有185所公立的中學、4所國際學校[268]以及14所华文獨立中學[269]。砂拉越的華文學校招收了許多原住民的學生[270]。砂拉越政府也估计当地居民就读學前教育[268]。

砂拉越目前有三所公立大學:馬來西亞砂拉越大學(UNIMAS)、玛拉工业大学(UiTM)的 哥打三马拉汉校區,以及马来西亚博特拉大学民都鲁校区。馬來西亞北方大學(UUM)也在古晋及詩巫設置了校外學習中心。砂拉越有三所私立大學:砂拉越科廷科技大學(1999)、斯威本科技大學砂拉越校區(2000)[266]及砂拉越科技大学学院(2013)。

砂拉越也提倡職業教育,以便为砂拉越再生能源走廊(SCORE)提供有技能的勞工。砂拉越也有許多社區學院[268]和四所師訓學院[271]。巴都林当師訓学院是马来西亚第三古老的師訓學院[272]。2015年時砂拉越的教育人力共有40,593人。[273]。

砂拉越州图书馆(PUSTAKA)是砂拉越最大的圖書館。此外,許多鄉鎮也都有公立及私立的圖書館[274]。

人口与族裔

根據2015年馬來西亞人口調查,砂拉越共有2,636,000人,為馬來西亞人口第四多的行政区[8]。然而,因為砂拉越面積很大,它的人口密度是全馬來西亞最低的,平均每平方千米仅有20人。2000至2010年其間,平均每年人口增長率為1.8%[7]。 2014年,總人口之58%居位於城市,其餘的42%居住於農村地區[276]。2011年,砂拉越的出生率為每一千人中的16.3人,死亡率為每一千人中的4.3人,婴儿死亡率為一千個嬰兒中的6.5人[277]。

砂拉越有超過四十個民族(實際種族為二十九至三十六個),各自均有自己的語言、習俗與文化。主要城市或市鎮的主要種族為馬來人、馬蘭諾人以及華人,還有少部份從家鄉出外打工的比達友人及伊班人[278]。砂拉越主要有六大種族,伊班族、馬來人、華人、比達友族、馬蘭諾族以及烏魯人[278]。其他少數民族有克達岩族、爪哇族、布吉人、 毛律族以及印度人[279]。砂拉越有超過十五萬名已登記的移民,他們大多從事種植業、製造業、建造業、服務業以及農業[280]。而非法移民數可能達三十二萬至三十五萬人[281]。

達雅族術語通常用來指伊班族和比达友族。 該術語通常在民族主義的景況中使用。[282] 2015年,馬來西亞聯邦政府承认“達雅族”为官方形式的術語。[283]馬來西亞土著指的是在馬來西亞半島,砂拉越和沙巴的馬來人和其他土著群體。這一群人在教育、就業、金融、政治常享有特權。[284] 原住民(Orang Asal)指的是馬來西亞所有的土著群體但不包括馬來人。[285]

伊班族

砂拉越有745,400個伊班族人,為全婆羅洲最多。[286]伊班族也稱為是海达雅族(Sea Dayaks)。大部份伊班族人信奉基督教。伊班族一開始住在拉让盆地附近,但在布魯克王朝的軍事行動之後,伊班族漸漸遷移到砂拉越的北邊。伊班族的房屋多半會是長屋,在以往猎头習俗盛行時,長屋也是一個防禦的單位。今日長屋仍是家庭中的象徵式符號。過去伊班族會將人分為三等,分別是「富有且勇敢的人」、「一般人」及「奴隸」。不過,在布魯克時期,伊班社群改組為正式職位,如本固鲁(社区领袖)和天猛公(最高酋長)[287]。伊班族仍保留許多傳統的習俗及信仰,例如死人節及丰收节

[288]。

华人

中国的商人于公元六世纪左右首次来到砂拉越地区。現今的砂拉越華人中有許多群體是起源自布魯克時期的移民[18]。来自中国的移民最初在富含金矿的石隆门担任劳工而非从事采矿,石隆门是19世纪上半叶砂越华人移民人数最多的地方[289]。在1857年以刘善邦为首领的十二华人矿工公司发起了反对布鲁克王朝的起义,但最终以失败告终。将近有四千余名华人在起义失败后遭到杀害,在1861年石隆门仅余下4户人家[289]。砂拉越華人中有許多不同的方言民系:廣府民系、福州民系、客家民系、閩南民系、潮州民系及興化民系。他們主要的節日有中元節及春節。砂拉越華人主要信奉佛教及基督教[50]。大部份古晉的华人都住在砂拉越河附近,也就是後來的古晉唐人街[290]。黄乃裳在1901年帶著他的族人到詩巫定居,住在拉让江附近[291]。華人後來去美里的煤礦坑及油田工作[290]。砂拉越華人曾受過中國國民黨及後來中国共产党的影響,[292]後來在1963年接受了砂拉越民族主义的意识形态[293]。

馬來人

砂拉越马来人的传统职业为渔民,他们沿河定居。如今他们则搬入城市定居,从事的职业遍布各行各业。马来人著名于他們的銀製品、銅製品、木雕以及紡織品[18]。有些马来人的村莊是在玛格丽塔堡附近的河邊,古晋清真寺後面,以及山都望山的山腳下[294]。有關砂拉越马来人的由來,有幾個不同的理論。據說是布鲁克首次用此一詞語稱呼住在海邊的砂拉越穆斯林原住民。不過也不是所有的砂拉越穆斯林都是马来人,大部份的马兰诺族也信仰伊斯蘭教[84]。其他的理論認為马来人是來自马来群岛(例如爪哇或苏门答腊)、中東,或是在文化及宗教改變後的砂拉越原住民[295]。

馬蘭諾人

馬蘭諾人原來就住在砂拉越,其中大部份是住在木膠的滨海小鎮[296],傳統上馬蘭諾人住在高屋(tall house)中,後來馬蘭諾人適應馬來人的生活後,住在村莊裡。馬蘭諾人的工作多半是漁夫、造船者及工匠。馬蘭諾人本來的信仰是異教,會慶祝考爾節,但現今大多數的馬蘭諾人是穆斯林[18][84][297]。

比达友族

比達友族主要居住在砂拉越的南端,如伦乐、 石隆门、西连、巴达旺。[298] 他們被稱為陸达雅族因為他們傳統住处是在石灰岩山區的陡峭。 它們是由幾個子族群组成的,如查格依、比亚达(Biatah)和瑟拉高(Selakau),但是各子族群所講的方言却互不相通。[299] 因此,他們接受英語和馬來語作為他們的共同語言。他們也因幾種樂器而著称,如:巨大的鼓和被稱為 pratuakng的竹制打擊樂器。 和伊班人一样,比达友族的傳統定居點是長屋,但他們也建立巴洛(baruk)圆屋以作社區會議场所。大多數比達友族是基督徒。[18]

烏魯人

烏魯人在伊班語中的意思是「住在上游的人」。 这包括很多住在砂拉越內陸上游生活的部落,如弄巴湾族、本南族、比薩揚人、肯雅族、加央族、加拉畢族和伯拉湾语族。[18] 他们以前曾經是獵頭族。他們大多住在巴里奧、布拉甲、巴卡拉兰和巴南河流域沿岸。[300] 他們以壁畫和木雕裝飾他們的長屋。他們也以造船,珠飾和紋身著称。[18] 烏魯人知名的樂器是卡扬族和肯雅族的沙貝、以及弄巴湾族的竹制樂器。加拉畢族和弄巴湾族以他們生產的香米著称。[300] 大多數烏魯人是基督教徒。[18]

宗教信仰

雖然伊斯蘭教是聯邦的官方宗教,但砂拉越並沒有官方的州教[302]。但是阿都拉曼耶谷就任首長期間,砂拉越憲法被修訂,使到馬來西亞最高元首成為砂拉越的伊斯蘭教首領,並授權州議會通過關於伊斯蘭教事務的法律。有了這樣的規定,在砂拉越可制定任何伊斯蘭教政策,也能创立伊斯蘭政府機構。1978年的伊斯蘭議會法案使到砂拉越能成立伊斯蘭法院,其管轄范围有婚姻、子女監護權、訂婚、繼承權,以及刑事案件等範疇。 卡迪法院也相繼被建立。[103]

砂拉越是馬來西亞是唯一一个基督徒人數超過穆斯林的州属。1848年,英國國教會(聖公會)最早来到砂拉越宣教,其次是天主教會和1903年的衛理公會。基督教先在華人社群中流傳,然后才在本來信仰泛靈論的土著間传播。[303] 砂拉越其他的基督信仰宗派有婆羅洲福音教會(也称为Sidang Injil Borneo或SIB)[304] 和浸礼宗。[305] 原住民如伊班族、比達友族、和烏魯人都开始信仰基督宗教,雖然他們还保留一些傳統宗教儀式。許多穆斯林來自馬來族、馬蘭諾族和卡扬族。馬來西亞華人主要信奉佛教,道教和中國民間信仰。[306] 砂拉越其他小规模宗教有巴哈伊信仰、[307]印度教、[308]锡克教[309]和泛靈論。[310]

- 砂拉越的主要宗教建筑

古晋圣约瑟教堂

旧砂拉越州清真寺

古晋鳳山寺

語言

1963年至1974年間,由於時任砂拉越首席部長史蒂芬·甘隆寧甘反對在砂拉越使用馬來語,英語是砂拉越的唯一法定語言[311]。1974年,新任首席部長阿都拉曼耶谷採納馬來語和英語為砂拉越的官方語言[103],並將學校的教學語言由英語改為馬來語[312]。現今,英語仍在法庭、州議會和部份政府機構中使用[313]。2015年11月18日,砂拉越首席部長阿德南宣佈,英語與馬來語共同被列為砂拉越的官方語言[314]。

在砂拉越使用的馬來語稱為砂拉越語(Bahasa Sarawak)或砂拉越馬來語,是砂拉越馬來人和其他土著主要使用的語言。砂拉越語是一個與馬來西亞半島的馬來語不同的方言。伊班語亦在砂拉越34%的人口中通用。比達友語設有6種主要方言,在砂拉越10%的人口中通用。烏魯族則使用30種不同的方言。華人則主要使用現代標準漢語,但他們亦使用閩南語(普遍為福建話,以及潮州話)、客家話和福州話等方言[315]。

文化

砂拉越博物馆

砂拉越呈现出富有代表性的民族特点、文化特色和多样化语言。早期,砂拉越文化由住在沿海地带的汶萊馬來人所影響。 中國和英國的文化也造成了可觀的文化影響。 獵頭曾經是伊班人的重要傳統,但是今日此傳統已无人遵守。[316] 基督教在加拉畢人和伦巴旺族的日常生活中扮演重要的角色,並改變了他們的民族特征。[317]本南族是最後一组放棄在叢林中的游牧生活方式的土著群體。[318][319] 異族通婚在砂拉越是一个很常見的现象。[320]

砂拉越文化村坐落在古晉的山都望山的山腳下。被譽為“活的博物館”,它展示各族裔群體在各自的傳統民居进行傳統活動。文化演出也在這裡展示。[321][322]砂拉越博物馆存放來自不同民族的文物如陶器、紡織品、和木雕工具,也集合當地文化的民族志材料。博物館保留了其法式建築风格。[323]其他的博物館包括

华人歷史博物館、[324]古晉貓博物館、[325] 伊斯蘭文化博物館、[326] 砂拉越紡織博物館、[327] 美術博物館、[328] 刘钦候医院纪念馆、[329] 巴南地區博物館。[330] 砂拉越布魯克时代,也建立了一系列保存完好的堡壘如:玛格烈达堡、[331]丝维雅堡、[332]愛麗絲堡[333]和爱玛堡(Fort Emma)[334]。

巴当艾度假村和巴旺阿山伊班長屋讓來訪的客人住一夜並让客人參加傳統的伊班日常活動。[335][336] 其他長屋包括:加帛伊班長屋、[337] 古晉比達友長屋;[338] 在巴里奧的加拉畢長屋、[339] 巴卡拉兰的弄巴湾長屋[340] 和詩巫的馬蘭諾木製房屋。[341] 老巴刹和亚答街是古晉唐人街其中两条著名的街道。[342][343] 古晉印度街著名於紡織產品。印度穆斯林清真寺可在附近找到。[344][345]

藝術及手工藝品

演奏沙貝的加央族人

砂拉越手工艺理事会負責宣傳砂拉越本地的民族工藝[346]。撒拉可拉夫樓閣設有示範一系列的手工藝技能的工作室[347]。砂拉越較著名的手工藝品包括烏魯族的珠饰品[348]、伊班族的伊班織布[349]、比達友族的席子和籃子、馬來人的马来织锦[321]和宋谷帽[350]以及華人的陶瓷[351]。砂拉越藝術家協會於1985年成立,透過畫作的形式提倡砂拉越文化和藝術[352][353]。砂拉越大部份藝術家戰後較喜歡使用自然風景、傳統舞蹈及傳統日常活動作為畫作的主題[354]。

烏魯族的沙貝是砂拉越著名樂器,並曾在1972年英女王伊利沙伯二世訪問砂拉越時演奏。它於1976年日本舉行的亞洲傳統表演藝術節期間首次在國際場合出現[355]。其他傳統樂器還包括锣、排式座鑼、體鳴樂器[356]、竹笛和齊特琴[357]。

伊班族戰士的英雄舞是砂拉越文化的一部份

口述傳統多年来已成為砂拉越土著文化的一部份,用以向年輕一代傳授生活知識、傳統及價值。這些故事由老人在特別場合和傳統演出時多次轉述給年青人[358]。伊班族的英雄舞[359]、民谣[360]、傳說[311],以及加央族和肯雅族的神話故事均為砂拉越的傳統習俗[361][362]。1958年至1977年間,婆罗洲文化局曾提倡將本地文化、本地作家和出版物以英語、華語、馬來語、伊班語和其他土著語言記錄。1977年,馬來西亞語言及文學研究院接替婆罗洲文化局,并只以馬來語記錄出版有關文獻[311]。土著口述傳統亦被馬來西亞砂拉越大學(UniMAS)和砂拉越習俗理事會(MAIS)記錄[358]。《砂勞越憲報》(Sarawak Gazette)於1870年由布魯克政府首度出版,紀錄有關砂拉越經濟、農業、人类学和考古学的新聞,至今仍然發行[363]。1876年在古晉發行的《戰士尼科薩的故事》(Hikayat Panglima Nikosa)是婆羅洲最早的文字著作之一[364]。《戰士尼科薩的故事》由艾哈邁德·夏瓦爾·哈米德·阿卜杜勒(Ahmad Syawal Abdul Hamid)所著,亦是馬來西亞的第一部小說[365]。砂拉越土著文化亦是砂拉越華人作家的寫作靈感來源之一[366]。

飲食

砂拉越叻沙

砂拉越著名的食物有叻沙[367]、哥羅麵(kolo mee)[368] 及砂拉越竹筒鸡[369][370]。砂拉越著名的甜點有砂拉越千层糕[371]。各族群在預備、烹調食物及飲食時都有其獨特的風格。不過現代的技術也影響了他們烹調食物的方式。各族群的食物有伊班人的米酒(tuak)、马兰诺人的西米棕榈饼干(tebaloi)及umai(加入蘭姆汁的生魚)及乌鲁族的urum giruq(布丁)[372]。砂拉越的傳統食物也使砂拉越成為美食旅游的好地點[373]。

當地的加盟連鎖餐廳有汉堡王(BK, Burger King)、肯德基(KFC)、麦当劳(McDonald's)、旧街场白咖啡(OldTown White Coffee)、必胜客(Pizza Hut)、星巴克(Starbucks)、栄寿司、新加坡鸡饭(Singapore Chicken Rice)、Kenny Rogers Roasters、Marrybrown、Nando's、Secret Recipe、The Chicken Rice Shop、Tony Roma's、曼哈顿鱼市场餐馆(Manhattan Fish Market)、舒戈邦(Sugar Bun)、Bing 咖啡、Seoul Garden韩式烧烤、Sushi King回转寿司[374]及寿司三味(Sushi Zanmai)。當地也可以找到像西方飲食、印尼飲食、印度飲食及中東飲食等來自各地的食物[375]。

媒體

一般認為砂拉越政府在媒體中有相當的影響力[311]。例如在砂拉越的《星洲日報》[376]、《诗华日报》、《婆罗洲邮报》及《婆罗洲前锋报》(Utusan Borneo)[377]。在1990年代,主要報章對砂拉越的反伐木路障給予負面的評價,認為不利於砂拉越的成長及發展[311]。《砂拉越论坛报》因為刊登了有關穆罕默德的諷刺漫畫,在2006年被永久停刊[378],此日報後來在2010年以《新砂拉越论坛报》的名稱重新發行[379]。英國記者凯丽·鲁卡瑟開設了砂拉越报告網站,以及以倫敦為基礎的短波無線電站,叫做《自由砂拉越电台》,以提供一些不一樣的,不受砂拉越政府干預的新聞及觀點[380]。

《砂拉越電台》在1954年開始,1976年結束,以馬來文、伊班文、華語及英語播放[311]。有些電台是以砂拉越為其基礎,像《砂拉越FM》[381]、《cats FM》[382]及《TEA FM》[383]。

假日及節慶

砂拉越華人宗教節慶時施放的烟火

砂拉越每年有許多的假日及節慶[384]。除了國定的马来西亚独立日及马来西亚日外,砂拉越在7月22日也會慶祝砂拉越自治日[385][386]及州元首的生日[387]。各族群也有各自的節日,因為開放日(open house)的傳統,也歡迎其他族群參與他們的節日慶祝[388][389][390]。砂拉越是馬來西亞唯一一個將达雅豐收節視為公假的州[391],也是唯一一個不將屠妖節視為公假的州[392]。在各大城镇中心,各宗教群體也可以自由的在其節日進行遊行[393]。砂拉越及沙巴是馬來西亞僅有两個將聖週五視為公定假日的州属[394]。古晋节(Kuching Festival)是長達一個月的活動,在每年八月舉行,以紀念古晋于1988年升格為市。[395]美里市日(Miri City Day)也和每年的美里五月节(Miri May Fest)一起舉行[396][397]。

体育

砂拉越分別在1958和1962年派出自己的團隊參加英聯邦運動會(共運會)[398],在1962年亞洲運動會後,1963年開始代表馬來西亞[399][400]。當地的砂拉越體育委員會在1985年成立,其目的為提高砂拉越的運動水平[401]。砂拉越在1990年和2016年主辦了馬來西亞運動會(馬運會),[402]也是1990年、1992年以及1994年馬運會的总冠軍[403]。砂拉越在東南亞運動會裡以馬來西亞代表參賽隊伍[404],並自1994年的馬來西亞殘障人士運動會以來連續11年得到總冠軍[405],砂拉越也另派出運動員參加過特殊奥林匹克运动会[406]。

在古晋省石隆门出生的潘德莉拉于2012年伦敦奥运获得10米跳台铜牌及

2016年里约热内卢奥运赢得双人10米跳台银牌。

在砂拉越有以下幾個體育場:砂拉越体育場、砂拉越州立體育場、团结體育館和砂拉越州曲棍球場[407]。1974年,砂拉越足球協會成立[408],並在馬來西亞足總盃(1992年)和馬來西亞甲級足球聯賽(1997年和2013年)中贏得冠軍[409]。

知名人物

| 族裔 | 政治 | 經濟 | 文化 | 教育 | 娛樂 |

华人 | 张健仁联邦内阁国内贸易与消费者事务部副部长,2018— 张庆信民进党主席、民都鲁国会议席国会议员,1999— | 张晓卿国内亿万富豪,常青集团创办人 林昌和升阳集团创办者 | 张晓卿星洲日报拥有者 詹敏珠女子亞洲象棋特級大師 | 刘利民东马首位董总主席,2015—2018 | 蔡明亮1994、2013年金马奖最佳导演奖 温子仁《速度与激情7》导演 张栋梁歌手 |

伊班人 | 詹姆士玛欣巴类州议员,1983— 史蒂芬·加隆·宁甘砂拉越州首席部长,1963—1966、1966 | 阿旺拉翁头人,1951年获乔治十字勋章 班乃迪克·三丁曾任砂拉越博物馆馆长 | 父亲为英国人亨利·高汀演员,《疯狂亚洲富豪》男主角 | ||

马来人 | 阿邦佐哈里砂拉越州首席部长,2017— 阿德南·沙甸砂拉越州首席部长,2014—2017 | ||||

马兰诺人 | 泰益玛目砂拉越州元首,2014— 拉曼耶谷砂拉越州首席部长,1970—1981 | ||||

比达友人 | 利察烈西连国会议员,1990— 詹姆士达弗联邦内阁天然资源与环境部副部长,2013—2018 | 潘德莉拉2016年里约奥运跳水银牌得主 布赖恩·尼克松·洛马斯2010年廣州亞運跳水雙面银牌得主 | 父亲为印尼华人德薇莉雅娜2014年大马世界小姐 | ||

烏魯人 | 伦巴旺族巴鲁比安联邦内阁工程部长,2018— | 华人与肯雅族混血刘拉丽莎2018年大马世界小姐 |

参看

- 北婆三邦

- 模板:砂拉越城镇与村落

注释

^ “砂拉越”为马来西亚华语规范理事会和砂拉越政府所承认的官方中文名。[22]

参考来源

^ Profil Negeri Sarawak (Sarawak state profile). Jabatan Penerangan Malaysia (Malaysian Information Department). [2016-01-12]. (原始内容存档于2015-04-21).

^ Sarawak State Anthem. Sarawak Government. [2016-01-12]. (原始内容存档于2015-09-07).

^ 西连陞格为省份. 东方日报. 2015年4月11日 [2016年11月2日].

^ Administrative Divisions and Districts. The Sarawak Government. [2015-07-23]. (原始内容存档于2015-07-23).

^ Yang di-Pertua Negeri. Sarawak Government. [2016-01-12]. (原始内容存档于2015-09-07).

^ Chief Minister of Sarawak. Sarawak Government. [2016-01-12]. (原始内容存档于2015-09-07).

^ 7.07.17.27.3 Sarawak – Facts and Figures 2011 (PDF). Sarawak State Planning Unit, Chief Minister Department: 5, 9, 15, 22. [2015-11-24]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2015-11-24).

^ 8.08.18.2 Population by States and Ethnic Group (各州的人口和民族统计). Department of Information, Ministry of Communications and Multimedia, Malaysia (马来西亚通讯和多媒体部). 2015 [2015-02-12]. (原始内容存档于2016-02-12).

^ Facts of Sarawak. The Sarawak Government. [2015-07-23]. (原始内容存档于2015-07-23).

^ Postal codes in Sarawak. cybo.com. [2015-07-23].

^ Postal codes in Miri. cybo.com. [2015-07-23].

^ Area codes in Sarawak(砂拉越的电话区号). cybo.com. [2015年7月22日].

^ Soon, Teh Wei. Some Little Known Facts On Malaysian Vehicle Registration Plates. Malaysian Digest. 2015-03-23 [2015-07-08]. (原始内容存档于2015-07-08).

^ 14.014.1 Rozan Yunos. Sultan Tengah — Sarawak's first Sultan (蘇丹登加 - 砂拉越第一位蘇丹). The Brunei Times (汶萊时报). 2008-12-28 [2014-04-03]. (原始内容存档于2014-04-03).

^ 15.015.1 The National Archives DO 169/254 (Constitutional issues in respect of North Borneo and Sarawak on joining the federation). The National Archives. 1961–1963 [2015-04-23].

^ 16.016.1 Vernon L. Porritt. British Colonial Rule in Sarawak, 1946–1963. Oxford University Press. 1997 [2016-05-07]. ISBN 978-983-56-0009-8.

^ 17.017.1 Philip Mathews. Chronicle of Malaysia: Fifty Years of Headline News, 1963–2013. Editions Didier Millet. 2014-02-28: 15–. ISBN 978-967-10617-4-9.

^ 18.0018.0118.0218.0318.0418.0518.0618.0718.0818.0918.1018.1118.1218.1318.1418.1518.16 Frans Welman. Borneo Trilogy Sarawak: Volume 2 (婆罗洲砂拉越三部曲:第2卷). Booksmango. : 132, 134, 136–138, 177 [2013-08-28]. ISBN 978-616-245-089-1.

^ Malaysia Act 1963 (Chapter 35) (PDF). The National Archives. United Kingdom legislation. [2011-08-12]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2012-11-14).

^ Governments of United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Federation of Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore. Agreement relating to Malaysia between United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Federation of Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore. 维基文库. 1963: p. 1.

Agreement relating to Malaysia between United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Federation of Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore. 维基文库. 1963: p. 1.

^ Yeng, Ai Chun. Malaysia Day now a public holiday, says PM. 2009-10-19 [2015-08-07].

^ https://sarawaktourism.com/zh-hans/前往砂拉越/

^ Origin of Place Names – Sarawak. National Library of Malaysia. 2000年 [2010年6月3日]. (原始内容存档于2008年2月9日).

^ Kris, Jitab. Wrong info on how Sarawak got its name. New Sunday Times. 1991-02-23 [2015-11-14].

^ 陈洁. 改,希望会更好!. 星洲网. 2012年12月26日 [2016年10月11日].

^ 马来西亚华语规范理事会简介. 国际时报 (砂拉越). 2008年7月20日 [2016年10月11日].

^ 27.027.1 Niah National Park – Early Human settlements. Sarawak Forestry. [2015-03-23]. (原始内容存档于2015-02-18).

^ 28.028.1 Faulkner, Neil. Niah Cave, Sarawak, Borneo. Current World Archaeology Issue 2. 2003-11-07 [2015-03-23]. (原始内容存档于2015-03-23).

^ History of the Great Cave of Niah. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. [2015-03-23]. (原始内容存档于2014-11-22).

^ Niah Cave. humanorigins.si.edu. Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. [2015-03-23]. (原始内容存档于2013-11-22).

^ Smith, Fumiko-Ikawa. Early Paleolithic in South and East Asia. Walter de Gruyter. 1978: 50 [2015-03-23]. ISBN 90-279-7899-9.

^ Hirst, K. Kris. Niah Cave (Borneo, Malaysia) – Anatomically modern humans in Borneo. about.com. [2015-03-23]. (原始内容存档于2013-12-23).

^ Niah National Park, Miri. Sarawak Tourism Board. [2015-12-26]. (原始内容存档于2015-12-26).

^ 山都望回想. 国际时报 (砂拉越). [2016-10-10].

^ Zheng, Dekun. Studies in Chinese Archeology. The Chinese University Press. 1982-01-01: 49, 50 [2015-12-29]. ISBN 9789622012615.In case of Santubong, its association with T'ang and Sung porcelain would necessary provide a date of about 8th – 13th century A.D.

^ Archeology. Sarawak Muzium Department. [2015-12-28]. (原始内容存档于2015-10-12).

^ Broek, Jan O.M. Place Names in 16th and 17th Century Borneo (在16世紀和17世紀的婆羅州地名). Imago Mundi. 1962, 16 (1): 134. JSTOR 1150309. doi:10.1080/03085696208592208.Carena (for Carena), deep in the bight, refers to Sarawak, the Kuching area, where there is clear archaeological evidence of an ancient trade center just inland from Santubong.

^ Donald F, Lach. Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume I: The Century of Discovery, Book 1 (在歐洲塑造下的亞洲,第1卷 - 100年的新发现,第一册). University of Chicago Publications 芝加哥大學出版社. 2008-07-15: 581 [2016-03-21]. ISBN 978-0-226-46708-5.... but Castanheda lists five great seaports that he says were known to the Portuguese. In his transcriptions they are called "Moduro" (Marudu?), "Cerava" (Sarawak?), "Laue" (Lawai), "Tanjapura" (Tanjungpura), and "Borneo" (Brunei) from which the island derives its name.

^ 39.039.139.239.339.439.5 Alastair, Morrison. Fair Land Sarawak: Some Recollections of an Expatriate Official (公平的國土砂拉越:外籍官員的一些回憶). SEAP Publications(東南亞研究計劃出版社). 1993-01-01: 10, 14, 95, 118–120 [2015-10-29]. ISBN 978-0-87727-712-5....the great Iban, and Kayan-Kenyah migrations were taking place inland, destroying or absorbing many of the former much less organised occupants of the land.(page 10) … Although nominal control of Sarawak coast continued, it came to exercised largely by semi-independent Malay chiefs, many of part Arab blood.(page 10)... There has been serious differences between Rajah and his brother and nephew (page 14) … The first Communist group to be formed in Sarawak... (page 95) … The first political party, the Sarawak United Peoples' Party (SUPP)...(page 118)... By 1962, there were six parties...(page 119)

^ Trudy, Ring; Noelle, Watson; Paul, Schellinger. Asia and Oceania: International Dictionary of Historic Places (亞洲和大洋洲:歷史区域的國際詞典). SEAP Publications(東南亞研究計劃出版社). 2012-11-12: 497 [2015-10-29]. ISBN 978-0-87727-712-5.The sultan of Brunei also had nominal control of the region, but he was interested in exacting a minor tax from the region. However, he interest grew when antimony (an element used in alloys and medicine) was discovered in the area in approximately 1824. Pangeran Mahkota, a Brunei prince, moved to Sarawak in the early nineteenth century and developed Kuching between 1824 and 1830. … As antimony mining increased, the Brunei Sultanate demanded higher taxes from Sarawak. This highly unpopular move led to civil unrest, which culminated in a revolt.

^ R, Reece. Empire in Your Backyard – Sir James Brooke (在你後院的帝國 - 詹姆斯·布魯克爵士). [2015-10-29]. (原始内容存档于2015年3月17日).

^ James Leasor. Singapore: The Battle That Changed the World(新加坡:改變世界的戰役). House of Stratus. 2001-01-01: 41–. ISBN 978-0-7551-0039-2.

^ Alex Middleton. Rajah Brooke and the Victorians (拉惹布魯克和維多利亞時代). The Historical Journal. June 2010, 53 (2): 381–400 [2014年12月24日]. ISSN 1469-5103. doi:10.1017/S0018246X10000063.

^ Mike, Reed. Book review of "The Name of Brooke – The End of White Rajah Rule in Sarawak" by R.H.W. Reece, Sarawak Literary Society, 1993 (书评:“布鲁克的名字 - 白人拉惹砂拉越统治的终结”R.H.W.里斯著,砂拉越文学社 1993年出版). sarawak.com.my. [2015-08-07]. (原始内容存档于2003-06-08).

^ James, Stuart Olson. Historical Dictionary of the British Empire, Volume 2. Greenwood Publishing Group. 1996: 982 [2015-10-29]. ISBN 978-0-313-29367-2.Brooke and his successors enlarged their realm by successive treaties of 1861, 1882, 1885, 1890, and 1905.

^ Chronology of Sarawak throughout the Brooke Era to Malaysia Day. The Borneo Post. 2011-09-16 [2015-10-29]. (原始内容存档于2015-02-06).1861 Sarawak is extended to Kidurong Point. … 1883 Sarawak extended to Baram River. … 1885 Acquisition of the Limbang area, from Brunei. … 1890 Limbang added to Sarawak. … 1905 Acquisition of the Lawas Region, from Brunei.

^ Lim, Kian Hock. A look at the civil administration of Sarawak. The Borneo Post. 2011-09-16 [2015-11-21]. (原始内容存档于2015-02-06).It seems the idea of dividing the state into divisions by the Brooke government was not implemented purely for administrative expediency but rather the divisions mark the new areas ceded by the Brunei government to the White Rajahs. This explains why the original five divisions of the state were so disproportionate in size.

^ Cuhaj, George S. Standard Catalog of World Paper Money, General Issues, 1368–1960. F+W Media. 2014: 1058 [2016-01-13]. ISBN 978-1-4402-4267-0.Sarawak was recognised as a separate state by the United States (1850) and Great Britain (1864), and voluntarily became a British protectorate in 1888.

^ Rujukan Kompak Sejarah PMR (Compact reference for PMR History subject). Arah Pendidikan Sdn Bhd. 2009: 82 [2016-01-13]. ISBN 9789833718818 (Malay). 引文格式1维护:未识别语文类型 (link)

^ 50.050.150.2 Frans, Welman. Borneo Trilogy Sarawak: Volume 1. Bangkok, Thailand: Booksmango. 2011: 177 [2015-11-02]. ISBN 9786162450822.The Brooke Dynasty ruled Sarawak for a hundred years and became famous as the "White Rajahs", accorded a status within the British Empire similar to that of the Indian Princes.

^ 51.051.151.251.351.451.5 Ooi, Keat Gin. Post-war Borneo, 1945–50: Nationalism, Empire and State-Building. Routledge. 2013: 7,93,98 [2015-11-02]. ISBN 978-1-134-05803-7.Personal rule with heavy dose of parternalism was adopted by the first two Rajahs, who saw themselves as enlightened monarchs entrusted with a mandate to rule on behalf of indigenous peoples' and well being … A Supreme Council comprising Malay Datus (non-royal chefs) advised rajah on all aspects of governance … The entry of western capitalist enterprises were greatly restricted. Christian missionaries tolerated, and Chinese immigration promoted as catalyst of economic development (mining, commerce, agriculture).(page 7)...This denial of entry to Anthony...(page 93)...The anti-cession movement was by the early 1950s effectively "strangled" a dead letter.(page 98)

^ Bintulu – Places of Interest. Bintulu Development Authority. [2015-07-19]. (原始内容存档于2016-11-19).

^ Marshall, Cavendish. World and Its Peoples: Eastern and Southern Asia, Volume 9. Bangladesh: Marshall Cavendish. 2007: 1182 [2015-11-02]. ISBN 978-0-7614-7642-9.Malays worked in the administration, Ibans (indigenous peoples of Sarawak) in the militia, and Chinese as workers in the plantations.

^ Lewis, Samuel Feuer. Imperialism and the Anti-Imperialist Mind. Transaction Publishers. 1989-01-01 [2015-11-02]. ISBN 978-1-4128-2599-3.Brooke made it his life task to bring to these jungles "prosperity, education, and hygiene"; he suppressed piracy, slave-trade, and headhunting, and lived simply in a thatched bungalow.

^ The Borneo Company Limited. National Library Board. [2016-01-25]. (原始内容存档于2015-10-12).

^ Sendou Ringgit, Danielle. The Bau Rebellion: What sparked it all?. The Borneo Post. 2015-04-05 [2016-03-22]. (原始内容存档于2016-03-22).The Rajah then came back days later with a bigger army and bigger guns aboard the Borneo Company steamer, the Sir James Brooke together with his nephew, Charles Brooke. Most of the Chinese miners were killed in Jugan, Siniawan where they had set up their defences while some managed to escape to Kalimantan.

^ 石隆门华工起义. 国际时报 [International Times (Sarawak)]. 2008年9月13日 [2016-03-22]. (原始内容存档于2013-01-24) (Chinese). 引文格式1维护:未识别语文类型 (link)

^ Ting, John. Colonialism and Brooke administration: Institutional buildings and infrastructure in 19th century Sarawak (PDF). University of Melbourne. [2016-01-13]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2015-09-22).Brooke also indigenised himself in terms of housing – his first residence was a Malay house. (page 9) … Government House (Fig. 3) was built after Brooke's first house was burnt down during the 1857 coup attempt. (page 10)

^ 59.059.159.2 Simon, Elegant. SARAWAK: A KINGDOM IN THE JUNGLE. The New York Times. 1986-07-13 [2015-11-02]. (原始内容存档于2015-11-02).The Istana, the palace built by the Brookes on a bend in the Sarawak River, still looks coolly over the muddy waters into the bustle of Kuching, the trading town James Brooke made his capital. … Today, the Istana is the State Governor's residence, … To protect his kingdom, Brooke built a series of forts in and around Kuching. Fort Margherita, named after Ranee Margaret, the wife of Charles, the second Rajah, was built about a mile downriver from the Istana.

^ Saiful, Bahari. Thrill is gone, state museum stuck in time — Public. The Borneo Post. 2015-06-23 [2015-11-02]. (原始内容存档于2015-10-02).The Sarawak Museum, being Borneo's oldest museum, should look into allocating a curator to be present and interacting with visitors at all times, he lamented.

^ Centenary of Brooke rule in Sarawak – New Democratic Constitution being introduced today. The Straits Times (Singapore). 1941-09-24 [2015-11-02].

^ 62.062.162.2 David, Leafe. The last of the White Rajahs: The extraordinary story of the Victorian adventurer who subjugated a vast swathe of Borneo. Daily Mail (UK). 2011-03-17 [2015-11-02]. (原始内容存档于2015-07-14).He denied these charges, but he was never allowed to inherit the rule of Sarawak because in 1946 Vyner agreed to cede it to the British Crown in return for a substantial financial settlement for him and his family. So it became Britain's last colonial acquisition.

^ Klemen, L. 日军进攻古晋 官员比百姓还惊慌. 风暴原记录. 2006年6月25日 [2016年9月18日].

^ Klemen, L. The Invasion of British Borneo in 1942. dutcheastindies.webs.com. 1999 [2015-11-03]. (原始内容存档于2015-04-01).

^ The Japanese Occupation (1941-1945). The Sarawak Government. [2015-11-03].

^ Gin, Ooi Keat. Wartime Borneo, 1941–1945: a tale of two occupied territories. Borneo Research Bulletin. 2013-01-01 [2015-11-03].Occupied Borneo was administratively partitioned into two halves, namely Kita Boruneo (Northern Borneo) that coincided with pre-war British Borneo (Sarawak, Brunei, and North Borneo) was governed by the IJA,...

^ Paul H, Kratoska. Southeast Asian Minorities in the Wartime Japanese Empire. Routledge. 2013-05-13: 136–142 [2015-11-03]. ISBN 978-1-136-12506-5.

^ 利旺拉甘:以抗日事迹.激发新生代献身精神. 国际时报(砂拉越). 2012年3月27日 [2016年11月2日].

^ Ooi, Keat Gin. Prelude to invasion: covert operations before the re-occupation of Northwest Borneo, 1944–45. Journal of the Australian War Memorial. [2015-11-03].However, as the situation developed, the SEMUT operations were divided into three distinct parties under individual commanders: SEMUT 1 under Major Tom Harrisson; SEMUT 2 led by Carter; and SEMUT 3 headed by Captain W.L.P. ("Bill") Sochon. The areas of operation were: SEMUT 1 the Trusan valley and its hinterland; SEMUT 2 the Baram valley and its hinterland; SEMUT 3 the entire Rejang valley. {22} Harrisson and members of SEMUT 1 parachuted into Bario in the Kelabit Highlands during the later part of March 1945. Initially, Harrisson established his base at Bario; then, in late May, shifted to Belawit in the Bawang valley (inside the former Dutch Borneo) upon the completion of an airstrip for light aircraft built entirely with native labour. In mid-April, Carter and his team (SEMUT 2) parachuted into Bario, by then securely an SRD base with full support of the Kelabit people. Shortly after their arrival, members of SEMUT 2 moved to the Baram valley and established themselves at Long Akah, the heartland of the Kenyahs. Carter also received assistance from the Kayans. Moving out from Carter's party in late May, Sochon led SEMUT 3 to Belaga in the Upper Rejang where he set up his base of operation. Kayans and Ibans supported and participated in SEMUT 3 operations.

^ Historical Monument – Surrender Point. Official Website of Labuan Corporation. Labuan Corporation. [2015-11-03].

^ Rainsford, Keith Carr. Surrender to Major-General Wootten at Labuan. Australian War Memorial. [2015-11-03].

^ HMAS Kapunda. Royal Australian Navy. [2016-06-12]. (原始内容存档于2016-03-27).

^ British Military Administration (August 1945 – April 1946). The Sarawak Government. [2015-11-03].

^ 华侨青年积极反让渡. 国际时报(砂拉越). [2016年9月17日].

^ 马来西亚50年去殖省思(下). 犀乡资讯网. [2016年9月17日].

^ Sarawak as a British Crown Colony (1946–1963). The Official Website of the Sarawak Government. [2015-11-07].

^ Mike, Thomson. The stabbed governor of Sarawak. BBC News. 2012-03-14 [2015-11-03].

^ 78.078.1 Anthony Brooke. The Daily Telegraph. 2011-03-06 [2015-11-03]....when his legal challenge to the cession was finally dismissed by the Privy Council in 1951, he renounced once and for all his claim to the throne of Sarawak and sent a cable to Kuching appealing to the anti-cessionists to cease their agitation and accept His Majesty's Government. The anti-cessionists instead continued their resistance to colonial rule until 1963, when Sarawak was included in the newly independent federation of Malaysia. Two years later, Anthony Brooke was welcomed back by the new Sarawak Government for a nostalgic visit.

^ 79.079.1 Tai, Yong Tan. Chapter Six: Borneo Territories and Brunei. Creating "Greater Malaysia": Decolonization and the Politics of Merger. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. 2008: 154–169 [2015-11-08]. ISBN 9789812307477.Underlying this was a general fear that without strong political institutions, ...

^ 80.080.1 Formation of Malaysia 16 September 1963 (1963年9月16日:馬來西亞形成). National Archives of Malaysia. [2015年11月8日].

^ JC, Fong. Formation of Malaysia. The Borneo Post. 2011年9月16日 [2015-11-08].

^ Trust and Non-self governing territories. United Nations. [2016-04-02]. (原始内容存档于2011-05-03).

^ United Nations Member States. United Nations. 2006-07-03 [2016-04-01]. (原始内容存档于2016-03-05).

^ 84.084.184.284.3 Ishikawa, Noboru. Between Frontiers: Nation and Identity in a Southeast Asian Borderland. Ohio University Press. 2010-03-15: 86–88,140,169 [2015-11-09]. ISBN 978-0-89680-476-0.The word "Malay" is widely used in Sarawak because in 1841 James Brooke brought it with him from Singapore, where it had been vaguely applied to all the coast-dwelling seafaring Muslims of the Indonesia Archipelago, particularly those of Sumatra and the Malayan Peninsula.

^ Brunei Revolt breaks out – 8 December 1962. Singapore National Library Board. [2015-11-09].The sultan of Brunei regarded the Malaysia project as "very attractive" and had indicated his interest in joining the federation. However, he was met with open opposition from within his country. The armed resistance challenging Brunei's entry into Malaysia that followed became a pretext for Indonesia to launch its policy of Konfrontasi (or Confrontation, 1963–1966) with Malaysia.

^ United Nations Treaty Registered No. 8029, Manila Accord between Philippines, Federation of Malaya and Indonesia (PDF). [2011-08-12]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2010-10-11).

^ United Nations Treaty Series No. 8809, Agreement relating to the implementation of the Manila Accord (PDF). [2011-08-12]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2011-10-12).

^ 砂劳越解放同盟(上). 国际时报 (砂拉越). 2006-08-08 [2015-02-11]. (原始内容存档于2012-03-17).

^ 砂劳越解放同盟(下). 国际时报 (砂拉越). 2006-08-29 [2015-02-11]. (原始内容存档于2012-03-17).

^ 北加里曼丹革命四十年 (PDF). 21 老友. of21.com: 99–102. [2015-02-11].

^ James, Chin. Book Review: The Rise and Fall of Communism in Sarawak 1940–1990. Kyoto Review of South East Asia. [2015-11-10].

^ 92.092.1 Chan, Francis; Wong, Phyllis. Saga of communist insurgency in Sarawak. The Borneo Post. 2011-09-16 [2013-01-10].

^ 十二公司#评价维基百科

^ 94.094.194.2 About Sarawak – Governance(關於砂拉越 - 治理). Official website of State Planning Unit – Chief Minister's Department of Sarawak (州策劃單位官方網站 - 砂拉越首長署). [2015年11月14日]. (原始内容存档于2013年9月13日).

^ My Constitution: Sabah, Sarawak and special interests(我的憲法:沙巴、砂拉越、和它们的特殊利益). Malaysian Bar(马来西亚律师公会). 2011年2月2日 [2015年11月13日]. (原始内容存档于2016年11月19日).

^ My Constitution: About Sabah and Sarawak (我的憲法:關於沙巴和砂拉越). Malaysian Bar. 2011-01-10 [2015-11-13]. (原始内容存档于2012-02-04).

^ Article 95D, Constitution of Malaysia (大馬憲法第95D條文). 訪問于2008年8月6日。

^ R.S, Milne; K.J, Ratnam. Malaysia: New States in a New Nation(馬來西亞:新州属在新的國家里). 羅德里奇. 2014: 71 [2015-11-14]. ISBN 978-1-135-16061-6.... the major parties in each state fall quite neatly into three categories: native-non-Muslim, native-Muslim, and non-native.

^ SPECIAL REPORT: The Ming Court Affair (subscription required)(特別報導:明阁事件(需要訂閱)). 当今大马. 2013-01-09 [2014年6月23日].

^ 100.0100.1 Chin, James. The Sarawak Chinese Voters and Their Support for the Democratic Action Party(砂拉越华人選民和他們對民主行動黨的支持) (PDF). Southeast Asian Studies (東南亞研究) (Kyoto University Research Information Repository (京都大學研究信息庫)). 1996, 34 (2): 387–401 [2014年6月19日].

^ Tawie, Joseph. SNAP faces more resignations over BN move (对于重新加入國陣的课题上,砂国民党面臨更多辭職). Free Malaysia Today(新今日大马). 2013-01-09 [2014年6月19日].

^ Mering, Raynore. Analysis: Party loyalty counts for little in Sarawak (分析:在砂拉越,黨员的忠誠度很小). The Malay Mail(馬來郵报). 2014-05-23 [2014年6月19日].

^ 103.0103.1103.2 Faisal, S Hazis. Domination and Contestation: Muslim Bumiputera Politics in Sarawak(統治和論爭:砂拉越穆斯林土著的政治). 東南亞研究所. 2012: 84, 86, 97 [2015-12-11]. ISBN 9789814311588.Rahman was responsible for inserting a provision on Islam, known as Article 4(1) and (2), in the negeri constitution, which states that "The Yang di-Pertuan Agong shall be the Head of religion of Islam in Sarawak" and the Council Negri is empowered to make provisions for regulating Islamic affairs through a Council to advise the Yang di-Pertuan Agong."(page 86) ... Rahman also introduced several policy changes aimed at accelerating the central state's Malaysianisation process. First, the strongman-politician introduced a motion in the Council Negri to make Bahasa Malaysia and English as negeri's official languages. The motion was unanimously passed on 26 March 1974.(page 84) ... The strongman-politician postponed the negeri election because he was not ready to face the wrath of opposition parties, especially PAJAR. Furthermore, SBN was facing an internal conflict over the allocation of negeri seats, especially after the inclusion of SNAP as the third member of the coalition. So, for the first time, parliamentary and negeri elections were held separately.(page 91)

^ Cheng, Lian. Why Sarawak is electorally unique (為什麼砂拉越選舉是獨特的). The Borneo Post. 2013-04-07 [2016-01-12]. (原始内容存档于2015-06-23).For this reason, Sarawak held its state and parliamentary elections separately and has been adhering to the practice since 1979 whereas all the other states still hold the two elections concurrently (see Table).

^ BN retains Sarawak, Taib sworn in as CM(國陣保留砂拉越,泰益宣誓就任首长). Free Malaysia Today(新今日大马). 2011年4月16日 [2014年6月23日].

^ Chua, Andy. DAP: Sarawak Pakatan formed to promote two-party system (民主行动党:砂拉越民联形成以促進兩线制). The Star (Malaysia) (Star Publications(马来西亚星报)). 2010年4月24日 [2014年6月23日]. (原始内容存档于2010年4月25日).

^ Ling, Sharon. Muhyiddin: Umno need not be in Sarawak (慕尤丁:巫統不必在砂拉越). 马来西亚星报. 2014年2月14日 [2014年6月23日].

^ 108.0108.1 Sarawak population. The Official Portal of the Sarawak Government. [2015-11-14]. (原始内容存档于2015-09-07).

^ TABURAN PENDUDUK MENGIKUT PBT & MUKIM 2010. 马来西亚国家统计局. [2017-12-15] (马来语).

^ Organisation Structure. Official Website of Ministry of Local Government and Community Development. [2015-11-14]. (原始内容存档于2014-09-07).

^ Nicholas, Taring. Imperialism in Southeast Asia. Routledge. 2003-08-29: 319 [2015-12-23]. ISBN 978-1-134-57081-2.Charles Brooke set up the Sarawak Rangers in 1862 as a paramilitary force for pacifying 'ulu' Dayaks.

^ Royal Ranger Regiment (Malaysia). discovermilitary.com. [2015-12-22]. (原始内容存档于2012-12-08).

^ Charles, de Ledesma; Mark, Lewis; Pauline, Savage. Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei. Rough Guides. 2003: 723 [2015-11-02]. ISBN 978-1-84353-094-7.In 1888, the three states of Sarawak, Sabah, and Brunei were transformed into protectorates, a status which handed over the responsibility for their foreign policy to the British in exchange for military protection.

^ John Grenville; Bernard Wasserstein. The Major International Treaties of the Twentieth Century: A History and Guide with Texts. Taylor & Francis. 2013-12-04: 608–. ISBN 978-1-135-19255-6.

^ Ninth schedule – Legislative lists. Commonwealth Legal Information Institute. [2015-12-22]. (原始内容存档于2014-09-15).

^ Chin Huat, Wong. Can Sarawak have an army?. Free Malaysia Today. 2011-09-27 [2015-12-22]. (原始内容存档于2015-12-22).

^ Jenifer Laeng. China Coast Guard vessel found at Luconia Shoals. The Borneo Post. 2015-06-03 [2015-06-03].

^ Presence of China Coast Guard ship at Luconia Shoals spooks local fishermen. The Borneo Post. 2015-09-27 [2015-09-28].

^ Ubaidillah Masli. Brunei drops all claims to Limbang. The Brunei Times. 2009-03-17 [2013-08-23]. (原始内容存档于2014-07-12).

^ Loss of James Shoal could wipe out state’s EEZ. The Borneo Post. 2014-02-05 [2014-05-17].

^ Border disputes differ for Indonesia, M'sia. Daily Express. 2015-10-16 [2015-10-16]. (原始内容存档于2016-02-16).

^ 122.0122.1122.2122.3122.4 Geography of Sarawak. Official website of state planning unit Chief Minister's Department of Sarawak. [2015-11-14]. (原始内容存档于2015-04-23).

^ Lambir Hills National Park. Sarawak Forestry Corporation. [2015-12-26]. (原始内容存档于2015-05-30).

^ Deer Cave and Lang's Cave. Mulu National Park. [2015-12-27]. (原始内容存档于2015-07-12).

^ Clearwater cave and Wind Cave. Gunung Mulu National Park. [2015-12-27]. (原始内容存档于2015-07-12).

^ Gunung Mulu National Park. Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board. [2015-12-27]. (原始内容存档于2015-10-17).

^ Gunung Mulu National Park. UNESCO. [2015-12-27]. (原始内容存档于2015-10-16).

^ 巴西班让, 古晋. 砂拉越旅游局. [2015-12-27]. (原始内容存档于2015-12-27).

^ Damai Beach Resort. Sarawak Tourism Board. [2015-12-27]. (原始内容存档于2015-12-27).

^ 丹绒巴都海滩, 民都鲁. 砂拉越旅游局. [2015-12-27]. (原始内容存档于2015-11-17).

^ 布莱登海滩 / 丹绒罗邦公园. 砂拉越旅游局. [2015-12-27]. (原始内容存档于2015-04-13).

^ 夏威夷沙滩. 砂拉越旅游局. [2015-12-27]. (原始内容存档于2015-04-13).

^ Medicinal plants around us. The Malaysian Nature Society (The Borneo Post). 2014-08-24 [2015-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2014-08-30).

^ Sarawak National Park – Biodiversity Conservation. Sarawak Forestry Department. [2015-11-17]. (原始内容存档于2015-11-17).

^ Rainforest is destroyed for palm oil plantations on Malaysia's island state of Sarawak (Image 1). The Daily Telegraph. [2014-08-21]. (原始内容存档于2011-02-06).

^ Rainforest is destroyed for palm oil plantations on Malaysia's island state of Sarawak (Image 2). The Daily Telegraph. [2014-08-21]. (原始内容存档于2011-02-08).

^ Rainforest is destroyed for palm oil plantations on Malaysia's island state of Sarawak (Image 3). The Daily Telegraph. [2014-08-21]. (原始内容存档于2011-02-07).

^ Sumatran Orangutans' rainforest home faces new threat. Agence France-Presse. The Borneo Post. 2013-05-05 [2014-08-21].

^ Nasalis larvatus. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008. International Union for Conservation of Nature. 2008.

^ 25 success stories. International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO): 44–45. [2015-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2015-06-13).

^ Semenggoh Nature Reserve. Sarawak Tourism Board. [2015-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2015-05-08).

^ Matang Wildlife Centre. Sarawak Tourism Board. [2015-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2015-05-14).

^ Talang-Satang National Park. Sarawak Tourism Board. [2015-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2015-11-16).

^ Birding in Sarawak. Sarawak Tourism Board. [2015-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2015-05-16).

^ 西米拉遥国家公园. Sarawak Toursim Board. [2015-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2015-05-08).

^ 到美里-实务地珊瑚礁国家公园潜水. 砂拉越旅游局. [2015-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2015-05-04).

^ 加丁山国家公园. 砂拉越旅游局. [2015-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2015-05-16).

^ 巴哥国家公园. 砂拉越旅游局官方网站. [2016年11月2日].

^ Padawan Pitcher Plant & Wild Orchid Centre. Sarawak Tourism Board. [2015-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2015-04-09).

^ The magnificent hornbills of Sarawak. The Borneo Post. 2015-07-12 [2015-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2015-08-06).

^ Forests Ordinance Chapter 126 (1958 edition) (PDF). Kuching, Sarawak: Sarawak Forestry Corporation. 1998-07-31 [2015-11-16]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2015-11-16).

^ Wild Life Protection Ordinance, 1998 – Chapter 26 (PDF). Kuching, Sarawak: Sarawak Forestry Corporation. 1998 [2015-11-16]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2015-11-16).

^ Malaysia:Sarawak Natural Parks and Nature Reserve Ordinance. GlobinMed. [2015-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2015-11-16).

^ Lian, Cheng. Protected wildlife on the menu. The Borneo Post. 2013-03-31 [2015-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2013-04-01).Hunting wild animals for food is a culture of Sarawak natives. Though most of them have adapted to modern ways, there are some groups such as the Penans still relying on wild animals as the main source of protein. As such, it is permissible for them to possess the meat of animals listed under the "restricted" category. These are wildlife which are protected but breeding in large number such as the wild boars. However, the meat to be taken should not exceed five kgs [sic] under the Wild Life Protection Ordinance 1998 (Amendment 2003).

^ History. Official website of Forest Department Sarawak. [2015-11-16].Mr. J.P. Mead became the first Conservator of Forests, Sarawak Forest Department, in 1919. The objectives of the Department were to manage and conserve the State's forest resources.

^ Barney, Chan. 6. INSTITUTIONAL RESTRUCTURING IN SARAWAK, MALAYSIA. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. [2015-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2012-07-19).

^ Sarawak Forestry Corporation – About Us – FAQ. Sarawak Forestry Corporation. [2015-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2015-05-12).

^ About Sarawak Biodiversity Centre – Profile. Sarawak Biodiversity Centre. [2015-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2014-12-06).

^ 159.0159.1 Joseph, Tawie. 'What's really left of our forest, Taib?'(泰益,我們的森林覆蓋率到底是多少?). Free Malaysia Today. 2012-10-25 [2015-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2012-11-02).

^ Lim, How Pim. Sarawak to maintain its 60 pct forest cover — Awang Tengah (砂拉越将維持其60巴仙的森林覆蓋率 - 阿旺登加). The Borneo Post. 2014-02-28 [2015-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2015-11-16).

^ Types and Categories of Sarawak's Forests (砂拉越州的森林分類和類型). Sarawak Forest Department. [2015-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2015-11-16).

^ Rhett, A. Butler. Google Earth reveals stark contrast between Sarawak’s damaged forests and those in neighboring Borneo states(谷歌地球發現砂拉越所破壞的森林和婆羅州其他的鄰國形成鮮明的對比). Mongabay. 2011-03-28 [2015-11-16].

^ Deforestation in Sarawak – Log tale(在砂拉越砍伐森林 - 木头的故事). The Economist. 2012-11-03 [2015-11-16]. (原始内容存档于2015-10-13).

^ Jerome, Chove; Jane, E Bryan; Philip, L Shearman; Gregory, P Asner; David, E Knapp; Geraldine, Aoro; Barbara, Lokes. Extreme Differences in Forest Degradation in Borneo: Comparing Practices in Sarawak, Sabah, and Brunei(婆羅洲森林退化的極端差異-比較在砂拉越,沙巴和文萊的伐木做法). Plos One. 2013-07-17, 8 (7): e69679. PMC 3714267. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069679.

^ New figures: palm oil destroys Malaysia’s peatswamp forests faster than ever (新的數字:棕櫚油比以往更快的速度破壞馬來西亞的泥炭沼澤森林). (Wetlands International)湿地国际. 2011-02-01 [2015-11-17]. (原始内容存档于2015-06-27).Between 2005–2010 almost 353,000 hectare of the one million hectare peat swamp forests were opened up at high speed; largely for palm oil production. In just 5 years time, almost 10% of all Sarawak's forests and 33% of the peat swamp forests have been cleared. Of this, 65% was for conversion to palm oil production.

^ Malaysia destroying its forests three times faster than all Asia combined(馬來西亞比所有亞洲国家更快三倍摧毀它自己的森林). The Daily Telegraph. 2011-02-01 [2015-11-17]. (原始内容存档于2015-11-17)."Total deforestation in Sarawak is 3.5 times as much as that for entire Asia, while deforestation of peat swamp forest is 11.7 times as much," the report said.

^ Tom, Young. Malaysian palm oil destroying forests, report warns (報告警告馬來西亞棕油业正在毀壞森林). The Guardian. 2011-02-02 [2015-07-28]. (原始内容存档于2014-05-29).The report from Wetlands International said palm oil plantations are being greatly expanded, largely in the Malaysian state of Sarawak on Borneo island. Unless the trend is halted, none of these forests will be left by the end of this decade, said Marcel Silvius, a senior scientist at Wetlands International. "As the timber resource has been depleted, the timber companies are now engaging in the oil palm business, completing the annihilation of Sarawak's peat swamp forests," he explained.

^ Elegant, Simon. Without a Trace(沒有踪影). 時代 (雜誌). 2001-09-03 [2014-08-14]. .

.

^ Sarawak and the Penan(砂拉越和本南人). [2015-11-17]. (原始内容存档于2015-07-08).When rainforest clearance began in the 1980s, it brought a massive upheaval to the Penan's way of life. Logging destroys not only nature, the basis of the Penan's livelihood, ... By erecting blockades on logging roads, they attempted to prevent further incursions by the timber companies. This resistance attracted a lot of international attention to the Penan, especially in the 1990s.

^ Native Customary Rights in Sarawak(砂拉越的土著習俗權利). Cultural Survival. [2015-11-17]. (原始内容存档于2015-10-05).Thus, the Ministry of Forestry possesses few official records distinguishing Native Customary Rights Land from timberland. Nevertheless, it consistently fails to conduct thorough investigations to determine boundaries, and approves logging concessions even though Native Customary Rights Land exists in a certain area.

^ Rumah Nor: A Land Rights Case for Malaysia (Rumah Nor:馬來西亞的土地權案例). The Borneo Project (婆羅洲計劃 ). [2015-11-17].In that precedent-setting court case of 2001, the High Court decided that Rumah Nor did indeed have sufficient evidence to claim native customary rights over all of their traditional territory … Though many High Court decisions since 2008 have chosen to uphold native land rights as defined in the Rumah Nor 2001 decision, hundreds of indigenous communities across Sarawak continue to face illegal land grabbing by government and corporations.

^ Jessica, Lawrence. Earth Island News – Borneo Project – Indigenous victory overturned (地球島新聞 - 婆羅洲計劃 - 土著的勝利被推翻). Earth Island Institute. [2015-11-17].

^ Rhett, Butler. Power, profit, and pollution: dams and the uncertain future of Sarawak (電力、利潤、和污染:水壩和砂拉越州不確定的未來). Mongabay. [2015-11-17].One dam has already displaced 10,000 native people and will flood an area the size of Singapore.

^ Bakun Dam(巴贡水电站). International Rivers(国际河流组织). [2015-11-17].

^ Sarawak, Malaysia(馬來西亞砂拉越). International Rivers(国际河流组织). [2015-11-17].Work on access roads to the dam site began but came to a halt in October 2013 when local communities launched two blockades to stop construction and other project preparations from proceeding.

^ Vanitha, Nadaraj. Battle Against Illegal Logging in Sarawak Begins(打擊砂拉越非法伐木活动已開始). The Establishment Post. 2015-09-21 [2015-11-18]. (原始内容存档于2015-09-21).

^ Mike Gaworecki. Sarawak establishes 2.2M acres of protected areas, may add 1.1M more (砂拉越建立220萬英畝的保護區,可能还會增加110萬英畝). Mongabay. 2016-08-19 [2016-08-22].

^ 178.0178.1178.2178.3178.4178.5178.6 The State of Sarawak. Malaysia Rating Corporation Berhad. [2015-11-12]. (原始内容存档于2015-11-18).

^ Chang, Ngee Hui. High Growth SMEs and Regional Development – The Sarawak Perspective. State Planning Unit, Sarawak Chief MInister Department. 2009 [2015-11-21]. (原始内容存档于2015-11-21).

^ Zoom on historical exchange rate graph (MYR to USD). fxtop.com. [2016-03-26]. (原始内容存档于2016-03-26).

^ Adrian, Lim. Sarawak achieves strong economic growth. The Borneo Post. 2014-02-28 [2015-11-18]. (原始内容存档于2015-07-07).

^ Selangor leads GDP contribution to national economy. Malay Mail. 2015-10-30 [2015-11-18]. (原始内容存档于2015-10-31).

^ Desmond, Davidson. Adenan pledges to keep fighting for 20% oil royalty. The Malaysian Insider. 2015-08-06 [2015-11-19]. (原始内容存档于2015-08-12).Sarawak Chief Minister Tan Sri Adenan Satem today admitted the oil and gas royalty negotiations – for a hike of 15% from 5% to 20% – with Petronas and Putrajaya have ended in deadlock, but has vowed to fight for it “as long as I'm alive”.

^ Rasoul, Sorkhabi. Borneo's Petroleum Plays 9 (4). GEO Ex Pro. 2012 [2015-11-20].A simplified map showing the distribution of major sedimentary basins onshore and offshore Borneo.

^ An overview of forest products statistics in South and Southeast Asia – National forest products statistics, Malaysia. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). [2015-11-18]. (原始内容存档于2015-07-24).In 2000, of the country’s total sawlog production of 23 million m3, Peninsular Malaysia contributed 22 percent, Sabah 16 percent, and Sarawak 62 percent. Sawlog production figures for 1996–2000 are shown in Table 2.

^ Sharon, Kong. Foreign banks in Sarawak. The Borneo Post. 2013-09-01 [2015-11-21]. (原始内容存档于2013-09-12).

^ Sarawak shakers. The Star (Malaysia). 2010-03-27 [2015-11-21].

^ Looi, Kah Yee. Chapter 5 – Income Inequality effects on growth-poverty relationship. A study the relationship between economic growth and poverty in Malaysia: 1970–2002 (Chapter 5). Universiti Malaya (Master Thesis). 2004: 86 [2015-11-21]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2012-04-06).

^ Midin, Salad; Yu, Ji. Addressing the poor-rich gap. The Star (Malaysia). 2011-11-23 [2015-11-21].PKR’s Batu Lintang assemblyman See Chee How told the house a week ago that, in 2009, Sarawak recorded 0.448 on the index. A decade before that, Sarawak had better results at 0.407.

^ 190.0190.1 Poverty in Sarawak now below 1%. The Star (Malaysia). 2015-08-27 [2015-11-23].

^ Sarawak unemployment at 4.6 pct in 2010. The Borneo Post. 2012-03-16 [2015-11-23]. (原始内容存档于2014-10-27).

^ 192.0192.1 Generation Portfolio. Sarawak Energy. [2015-11-23]. (原始内容存档于2013-11-24).

^ 193.0193.1 Hydroelectric Power Dams in Sarawak. Sarawak Integrated Water Resources – Management Master Plan. [2015-11-23]. (原始内容存档于2015-11-23).

^ Jack, Wong. Bakun at 50% capacity producing 900MW. The Star (Malaysia). 2014-07-22 [2015-11-23].

^ Christopher, Lindom. Making HEPs in Sarawak safe. New Sarawak Tribune. 2015-07-11 [2015-11-23]. (原始内容存档于2015-11-23).... Murum HEP had officially started commercial operation on 8 June 2015,"...

^ Core Business Activities. Sarawak Energy. [2015-11-23]. (原始内容存档于2015-07-10).

^ Wong, Jack. Sarawak Energy needs to raise generating capacity to 7,000 MW. The Star (Malaysia). 2014-05-12 [2015-11-23].

^ CK Tan. Malaysia exports electricity to Indonesia. Nikkei Asian Review. 2016-05-12 [2016-05-15]. (原始内容存档于2016-05-15).

^ Research and Development – Introduction To Renewable Energy. Sarawak Energy. [2015-11-23]. (原始内容存档于2015-07-09).

^ Development Strategy. Regional Corridor Development Authority. [2015-11-22]. (原始内容存档于2015-11-17).

^ What is SCORE?. Regional Corridor Development Authority. [2015-11-22]. (原始内容存档于2015-11-17).

^ Sarawak Corridor of Renewable Energy – Register your interest. Sarawak Corridor of Renewable Energy. [2015-07-26]. (原始内容存档于2014-06-27).

^ What is RECODA. Regional Corridor Development Authority. [2015-11-22]. (原始内容存档于2015-11-17).

^ SCORE Areas. Sarawak Corridor of Renewable Energy. [2015-07-31]. (原始内容存档于2014-06-27).

^ Samalaju – SCORE. Regional Corridor Development Authority. [2015-11-22]. (原始内容存档于2015-11-17).

^ Tanjung Manis – SCORE. Regional Corridor Development Authority. [2015-11-22]. (原始内容存档于2015-11-17).

^ Mukah – SCORE. Regional Corridor Development Authority. [2015-11-22]. (原始内容存档于2015-11-17).

^ 208.0208.1 Fewer tourists visited Sarawak last year, DUN told. The Borneo Post. [2016-06-16].

^ 209.0209.1 Sarawak's tourism strategy focuses on sustainable development. Oxford Business Group. [2015-11-21]. (原始内容存档于2015-11-21).

^ Ava, Lai. Valuable prizes await Hornbill winners. The Star (Malaysia). 2015-07-29 [2015-11-20].The awards are co-organised by the Ministry of Tourism Sarawak and Sarawak Tourism Federation to recognise individuals or organisations’ contribution to the development of tourism in Sarawak and to create a culture of excellence, creativity, quality services and best practices.

^ Sarawak fest certain to be a rare treat. Bangkok Post. 2011-02-22 [2015-11-20]. .

.

^ 《星洲日报电子报》砂拉越中区民都鲁版页15,2018年9月19日

^ Siniawan Heritage Fiesta 2018Hornbill Trail Newspaper,2018/08/17

^ Shopping Malls in Kuching. Sarawak Tourism Board. [2015-12-28]. (原始内容存档于2015-12-28).

^ Shopping Malls in Miri. Sarawak Tourism Board. [2015-12-28]. (原始内容存档于2015-02-04).

^ Kathleen, Peddicord. The Most Interesting Retirement Spot You’ve Never Heard Of. U.S. News & World Report. 2012-12-10 [2015-11-21]. (原始内容存档于2014-04-10).

^ Jean, Fogler. Retirement Abroad: 5 Unexpected Foreign Cities. Investopedia. [2015-11-21]. (原始内容存档于2015-04-20).

^ Why Malaysia is one of the top 3 countries for retirement. HSBC Bank Malaysia. [2015-11-21]. (原始内容存档于2015-09-07).

^ 219.0219.1 Pulling more tourists to Sarawak. The Borneo Post. [2015-07-07]. (原始内容存档于2015-08-19).

^ 去年约486万旅客来砂 摆脱连续两年负成长窘境. 诗华日报online. 2018年2月27日 [2018年9月24日].

^ 李景胜望能开辟更多砂中直航. 星洲网. 2018年7月18日 [2018年9月28日].

^ Pg.7 PROPERTY MARKET REVIEW 2016 AND OUTLOOK 2017CH Williams Talhar Wong & Yeo Sdn Bhd,2016年12月

^ Visitor Arrivals into Sarawak 2015 (PDF). Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture Sarawak. [2016-05-31]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2016-07-01).

^ OECD Investment Policy Reviews OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Malaysia 2013. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Publishing. 2013-10-30: 234 [2015-12-17]. ISBN 9789264194588.All the same, there are important variations in the quantity and quality of infrastructure stocks, with infrastructure more developed in peninsular Malaysia than in Sabah and Sarawak.

^ About Us. MIDCom. [2015-12-17]. (原始内容存档于2015-12-22).

^ Industrial Estate by Division. Official Website of the Sarawak Government. [2015-12-17]. (原始内容存档于2015-07-04).

^ H., Borhanazad; S., Mekhilef; R, Saidur; G., Boroumandijazi. Potential application of renewable energy for rural electrification in Malaysia (PDF). Renewable Energy. 2013, 59: 211 [2015-11-23].

^ 228.0228.1 Alexandra, Lorna; Doreen, Ling. Infrastructure crucial to state's goals. New Sarawak Tribune. 2015-10-09 [2015-12-16]. (原始内容存档于2015-12-16)."In 2014, 82% of houses located in Sarawak rural areas have access to water supply in comparison to 59% in 2009." Fadillah also said that the rural electricity coverage had improved over the last few years with 91% of the households in Sarawak having access to electricity in 2014 compared to 67% in 2009.

^ New technologies play a major role in Sarawak’s development plans. Oxford Business Group. [2015-12-17]. (原始内容存档于2015-12-17).

^ Mohd, Hafiz Mahpar. Cahya Mata Sarawak buys 50% of Sacofa for RM186m. The Star (Malaysia). 2015-04-02 [2015-12-17].

^ About SAINS – Corporate Profile. Sarawak Information Systems Sdn Bhd. [2015-12-17].

^ Pos Malaysia wheels brings mobile postal service to Lawas. Bernama. 2012-02-15 [2015-12-17]. (原始内容存档于2015-12-17).

^ Adib, Povera. Postal services improving in Sabah and S’wak. New Straits Times. 2015-10-29 [2015-12-17].

^ 234.0234.1234.2234.3 Transport and Infrastructure. Official Website of the Sarawak Government. [2015-12-17]. (原始内容存档于2015-09-07).

^ Harun, Jau. New department being set up. New Sarawak Tribune. 2015-08-08 [2015-12-17]. (原始内容存档于2015-12-17).

^ 236.0236.1236.2236.3236.4236.5 New land, air and sea transport links will help meet higher demand in Sarawak. Oxford Business Group. [2015-12-17]. (原始内容存档于2015-12-17).

^ Then, Stephen. Repair Pan Borneo Highway now, says Bintulu MP following latest fatal accident. The Star (Malaysia). 2013-09-13 [2014-06-23].

^ Thiessen, Tamara. Borneo:Sabah, Brunei, Sarawak. Bradt Travel Guides. 2012: 98 [2016-01-26]. ISBN 978-1-84162-390-0.All major roads are dual carriageways; there are no multi-lane expressways. In Malaysia, you drive on the left-hand side of the road and cars are right-hand drive.

^ Yap, Jacky. 46 Things you Didn't Know about Kuching. Vulcan Post. [2016-01-26]. (原始内容存档于2015-06-15).

^ Airlines flying from Malaysia to Kuching. [2016-03-30]. (原始内容存档于2016-03-30).

^ Hornbill Skyways – Wings to your destination. Hornbill Skyways. [2016-03-30]. (原始内容存档于2016-03-19).

^ September Express Air Buka Rute ke KuchingTribun News,2013年8月28日

^ AirAsia’s Kuching-Pontianak flight boosts state’s tourism — Abdul KarimBorneo Post Online,2017年6月6日

^ Lion Air may also fly Pontianak-Kuching or Pontianak-Miri sectorBorneo Post Online,2017年12月6日

^ Wings Air Buka Rute Pontianak-Kuching. Harian Nasional. 2018年1月5日.

^ Kuching—ShenzhenAirasia,2017年12月2日

^ 阿邦佐澄清计划没终止 轻快铁只是暂搁置. 诗华日报online. 2018年9月1日 [2018年9月24日].

^ 明年动工,先建三条·晋轻快铁6年后载客. 星洲网. 2018年3月30日 [2018年9月24日].

^ 达迈 西连 古晋市·轻快铁分3主线. 星洲网. 2018年3月30日 [2018年9月24日].