Endocrine system

| Endocrine system | |

|---|---|

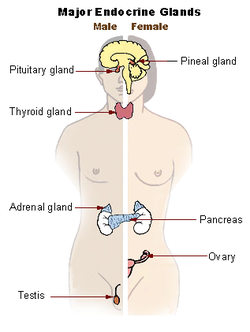

Main glands of the endocrine system. Note that the thymus is no longer considered part of the endocrine system, as it does not produce hormones. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Systema endocrinum |

| MeSH | D004703 |

| FMA | 9584 |

Anatomical terminology [edit on Wikidata] | |

The endocrine system is a chemical messenger system consisting of hormones, the group of glands of an organism that carry those hormones directly into the circulatory system to be secreted to distant target organs, and the feedback loops of homeostasis that the hormones drive. In humans, the major endocrine glands are the thyroid gland and the adrenal glands. In vertebrates, the hypothalamus is the neural control center for all endocrine systems. The field of study dealing with the endocrine system and its disorders is endocrinology, a branch of internal medicine.[1]

Special features of endocrine glands are, in general, their ductless nature, their vascularity, and commonly the presence of intracellular vacuoles or granules that store their hormones. In contrast, exocrine glands, such as salivary glands, sweat glands, and glands within the gastrointestinal tract, tend to be much less vascular and have ducts or a hollow lumen. A number of glands that signal each other in sequence are usually referred to as an axis, for example, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.

In addition to the specialized endocrine organs mentioned above, many other organs that are part of other body systems, such as bone, kidney, liver, heart and gonads, have secondary endocrine functions. For example, the kidney secretes endocrine hormones such as erythropoietin and renin. Hormones can consist of either amino acid complexes, steroids, eicosanoids, leukotrienes, or prostaglandins.[1]

The endocrine system is in contrast to the exocrine system, which secretes its hormones to the outside of the body using ducts. As opposed to endocrine factors that travel considerably longer distances via the circulatory system, other signaling molecules, such as paracrine factors involved in paracrine signalling diffuse over a relatively short distance.

The word endocrine derives via New Latin from the Greek words ἔνδον, endon, "inside, within," and "exocrine" from the κρίνω, krīnō, "to separate, distinguish".

Contents

1 Structure

1.1 Major endocrine systems

1.2 Glands

1.3 Cells

2 Development

3 Function

3.1 Hormones

3.2 Cell signalling

3.2.1 Autocrine

3.2.2 Paracrine

3.2.3 Juxtacrine

4 Clinical significance

4.1 Disease

5 Other animals

6 Additional images

7 See also

8 References

9 External links

Structure

Major endocrine systems

The human endocrine system consists of several systems that operate via feedback loops. Several important feedback systems are mediated via the hypothalamus and pituitary.[2]

- TRH – TSH – T3/T4

- GnRH – LH/FSH – sex hormones

- CRH – ACTH – cortisol

- Renin – angiotensin – aldosterone

- leptin vs. insulin

Glands

Endocrine glands are glands of the endocrine system that secrete their products, hormones, directly into interstitial spaces and then absorbed into blood rather than through a duct. The major glands of the endocrine system include the pineal gland, pituitary gland, pancreas, ovaries, testes, thyroid gland, parathyroid gland, hypothalamus and adrenal glands. The hypothalamus and pituitary gland are neuroendocrine organs.

Cells

There are many types of cells that comprise the endocrine system and these cells typically make up larger tissues and organs that function within and outside of the endocrine system.

- Hypothalamus

- Anterior Pituitary Gland

- Pineal Gland

- Posterior Pituitary Gland

Thyroid Gland

Follicular cells of the thyroid gland produce and secrete T3 and T4 in response to elevated levels of TRH, produced by the hypothalamus, and subsequent elevated levels of TSH, produced by the anterior pituitary gland, which further regulates the metabolic activity and rate of all cells, including cell growth and tissue differentiation.

Parathyroid Gland

Epithelial cells of the parathyroid glands are richly supplied with blood from the inferior and superior thyroid arteries and secrete parathyroid hormone (PTH). PTH acts on bone, the kidneys, and the GI tract to increase calcium reabsorption and phsophate excretion. In addition, PTH stimulates the conversion of Vitamin D to its most active variant, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, which further stimulates calcium absorption in the GI tract.[1]

Adrenal Glands

- Adrenal Cortex

- Adrenal Medulla

Pancreas

- Alpha Cells

- Beta Cells

- Delta Cells

- F Cells

- Ovaries

- Testis

Development

Function

Hormones

A hormone is a class of signaling molecules produced by glands in multicellular organisms that are transported by the circulatory system to target distant organs to regulate physiology and behaviour. Hormones have diverse chemical structures, mainly of 3 classes: eicosanoids, steroids, and amino acid/protein derivatives (amines, peptides, and proteins). The glands that secrete hormones comprise the endocrine system. The term hormone is sometimes extended to include chemicals produced by cells that affect the same cell (autocrine or intracrine signalling) or nearby cells (paracrine signalling).

Hormones are used to communicate between organs and tissues for physiological regulation and behavioral activities, such as digestion, metabolism, respiration, tissue function, sensory perception, sleep, excretion, lactation, stress, growth and development, movement, reproduction, and mood.[3][4]

Hormones affect distant cells by binding to specific receptor proteins in the target cell resulting in a change in cell function. When a hormone binds to the receptor, it results in the activation of a signal transduction pathway. This may lead to cell type-specific responses that include rapid non-genomic effects or slower genomic[disambiguation needed] responses where the hormones acting through their receptors activate gene transcription resulting in increased expression of target proteins. Amino acid–based hormones (amines and peptide or protein hormones) are water-soluble and act on the surface of target cells via second messengers; steroid hormones, being lipid-soluble, move through the plasma membranes of target cells (both cytoplasmic and nuclear) to act within their nuclei.

Cell signalling

The typical mode of cell signalling in the endocrine system is endocrine signaling, that is, using the circulatory system to reach distant target organs. However, there are also other modes, i.e., paracrine, autocrine, and neuroendocrine signaling. Purely neurocrine signaling between neurons, on the other hand, belongs completely to the nervous system.

Autocrine

Autocrine signaling is a form of signaling in which a cell secretes a hormone or chemical messenger (called the autocrine agent) that binds to autocrine receptors on the same cell, leading to changes in the cells.

Paracrine

Some endocrinologists and clinicians include the paracrine system as part of the endocrine system, but there is not consensus. Paracrines are slower acting, targeting cells in the same tissue or organ. An example of this is somatostatin which is released by some pancreatic cells and targets other pancreatic cells.[1]

Juxtacrine

Juxtacrine signaling is a type of intercellular communication that is transmitted via oligosaccharide, lipid, or protein components of a cell membrane, and may affect either the emitting cell or the immediately adjacent cells.[5]

It occurs between adjacent cells that possess broad patches of closely opposed plasma membrane linked by transmembrane channels known as connexons. The gap between the cells can usually be between only 2 and 4 nm.[6]

Clinical significance

Disease

Disability-adjusted life year for endocrine disorders per 100,000 inhabitants in 2002.[7].mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

no data

less than 80

80–160

160–240

240–320

320–400

400–480

480–560

560–640

640–720

720–800

800–1000

more than 1000

Diseases of the endocrine system are common,[8] including conditions such as diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, and obesity.

Endocrine disease is characterized by misregulated hormone release (a productive pituitary adenoma), inappropriate response to signaling (hypothyroidism), lack of a gland (diabetes mellitus type 1, diminished erythropoiesis in chronic renal failure), or structural enlargement in a critical site such as the thyroid (toxic multinodular goitre). Hypofunction of endocrine glands can occur as a result of loss of reserve, hyposecretion, agenesis, atrophy, or active destruction. Hyperfunction can occur as a result of hypersecretion, loss of suppression, hyperplastic or neoplastic change, or hyperstimulation.

Endocrinopathies are classified as primary, secondary, or tertiary. Primary endocrine disease inhibits the action of downstream glands. Secondary endocrine disease is indicative of a problem with the pituitary gland. Tertiary endocrine disease is associated with dysfunction of the hypothalamus and its releasing hormones.[citation needed]

As the thyroid, and hormones have been implicated in signaling distant tissues to proliferate, for example, the estrogen receptor has been shown to be involved in certain breast cancers. Endocrine, paracrine, and autocrine signaling have all been implicated in proliferation, one of the required steps of oncogenesis.[9]

Other common diseases that result from endocrine dysfunction include Addison's disease, Cushing's disease and Graves' disease. Cushing's disease and Addison's disease are pathologies involving the dysfunction of the adrenal gland. Dysfunction in the adrenal gland could be due to primary or secondary factors and can result in hypercortisolism or hypocortisolism . Cushing's disease is characterized by the hypersecretion of the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) due to a pituitary adenoma that ultimately causes endogenous hypercortisolism by stimulating the adrenal glands.[10] Some clinical signs of Cushing's disease include obesity, moon face, and hirsutism.[11] Addison's disease is an endocrine disease that results from hypocortisolism caused by adrenal gland insufficiency. Adrenal insufficiency is significant because it is correlated with decreased ability to maintain blood pressure and blood sugar, a defect that can prove to be fatal.[12]

Graves' disease involves the hyperactivity of the thyroid gland which produces the T3 and T4 hormones.[11]Graves' disease effects range from excess sweating, fatigue, heat intolerance and high blood pressure to swelling of the eyes that causes redness, puffiness and in rare cases reduced or double vision.[6]

Other animals

A neuroendocrine system has been observed in all animals with a nervous system and all vertebrates have an hypothalamus-pituitary axis.[13] All vertebrates have a thyroid, which in amphibians is also crucial for transformation of larvae into adult form.[14][15] All vertebrates have adrenal gland tissue, with mammals unique in having it organized into layers.[16] All vertebrates have some form of a renin–angiotensin axis, and all tetrapods have aldosterone as a primary mineralocorticoid.[17][18]

Additional images

Female endocrine system.

Male endocrine system

See also

- Endocrine disease

- Endocrinology

- List of human endocrine organs and actions

- Neuroendocrinology

- Nervous system

- Paracrine signalling

- Releasing hormones

- Tropic hormone

References

^ abcd Marieb, Elaine (2014). Anatomy & physiology. Glenview, IL: Pearson Education, Inc. ISBN 978-0321861580..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Sherwood, L. (1997). Human Physiology: From Cells to Systems. Wadsworth Pub Co. ISBN 978-0495391845.

^ Neave N (2008). Hormones and behaviour: a psychological approach. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0521692014. Lay summary – Project Muse.

^ "Hormones". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

^ Gilbert, Scott F. (2000-01-01). "Juxtacrine Signaling".

^ ab Vander, Arthur (2008). Vander's Human Physiology: the mechanisms of body function. Boston: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. pp. 332–333. ISBN 978-0073049625.

^ "Mortality and Burden of Disease Estimates for WHO Member States in 2002" (xls). World Health Organization. 2002.

^ Kasper (2005). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. McGraw Hill. p. 2074. ISBN 978-0-07-139140-5.

^ Bhowmick NA, Chytil A, Plieth D, Gorska AE, Dumont N, Shappell S, Washington MK, Neilson EG, Moses HL (2004). "TGF-beta signaling in fibroblasts modulates the oncogenic potential of adjacent epithelia". Science. 303 (5659): 848–51. Bibcode:2004Sci...303..848B. doi:10.1126/science.1090922. PMID 14764882.

^ Buliman A, Tataranu LG, Paun DL, Mirica A, Dumitrache C (2016). "Cushing's disease: a multidisciplinary overview of the clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment". Journal of Medicine & Life. 9 (1): 12–18. PMC 5152600. PMID 27974908.

^ ab Vander, Arthur (2008). Vander's Human Physiology: the mechanisms of body function. Boston: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. pp. 345–347.

ISBN 007304962X.

^ Inder, Warrick J.; Meyer, Caroline; Hunt, Penny J. (2015-06-01). "Management of hypertension and heart failure in patients with Addison's disease". Clinical Endocrinology. 82 (6): 789–792. doi:10.1111/cen.12592. PMID 25138826.

^ Hartenstein V (September 2006). "The neuroendocrine system of invertebrates: a developmental and evolutionary perspective". The Journal of Endocrinology. 190 (3): 555–70. doi:10.1677/joe.1.06964. PMID 17003257.

^ Dickhoff, Walton W.; Darling, Douglas S. (1983). "Evolution of Thyroid Function and Its Control in Lower Vertebrates". American Zoologist. 23 (3): 697–707. doi:10.1093/icb/23.3.697. JSTOR 3882951.

^ Galton, Valerie Anne (1 January 1988). "The Role of Thyroid Hormone in Amphibian Development". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 28 (2): 309–18. doi:10.1093/icb/28.2.309. JSTOR 3883279.

^ Pohorecky LA, Wurtman RJ (March 1971). "Adrenocortical control of epinephrine synthesis". Pharmacological Reviews. 23 (1): 1–35. PMID 4941407.

^ Wilson JX (1984). "The renin–angiotensin system in nonmammalian vertebrates". Endocrine Reviews. 5 (1): 45–61. doi:10.1210/edrv-5-1-45. PMID 6368215.

^ Colombo L, Dalla Valle L, Fiore C, Armanini D, Belvedere P (April 2006). "Aldosterone and the conquest of land". Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 29 (4): 373–9. doi:10.1007/bf03344112. PMID 16699307.

External links

| The Wikibook Human Physiology has a page on the topic of: The endocrine system |

| The Wikibook Anatomy and Physiology of Animals has a page on the topic of: Endocrine System |

Library resources about Endocrine system |

|

Media related to Endocrine system at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Endocrine system at Wikimedia Commons