Mahican

Multi tool use

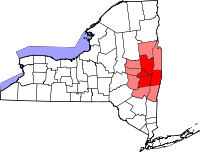

Historic territory of the Mahicans | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

c. 3,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

English (originally Mahican) | |

| Religion | |

| Moravian Church | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

Lenape, Mohegan, Pequot |

The Mahican (/məˈhiːkən/ or Mohican /moʊˈhiːkən/) are an Eastern Algonquian Native American tribe that was Algonquian-speaking. As part of the Algonquian family of tribes, they were related to the abutting Lenape, who occupied territory to the south as far as the Atlantic coast. The Mahican occupied the upper Hudson River Valley (around the confluence of the Mohawk River, where present-day Albany, New York, developed) and into western New England centered on present-day Pittsfield, Massachusetts, and lower Vermont. After 1680, due to conflicts with the Mohawk during the Beaver Wars, many were driven southeastward across the present-day Massachusetts western border and the Berkshires to Berkshire County around Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

Since the forcible relocation of Native American populations to reservations in the American West during the 1830s, most descendants of the Mahican are located in Shawano County, Wisconsin. Decades later they eventually formed the federally recognized Stockbridge-Munsee Community with registered members of the Leni Lenape people and have a 22,000-acre (89 km2) reservation.

Following the disruption of the American Revolutionary War, most of the Mahican descendants first migrated westward to join the Iroquois Oneida on their reservation in central New York. The Oneida gave them about 22,000 acres for their use. After more than two decades, in the 1820s and 1830s, the Oneida and the Stockbridge moved again, pressured to relocate to northeastern Wisconsin under the federal Indian Removal program.[1]

The tribe identified by the place where they lived: "Muh-he-ka-neew" (or "People of the continually flowing waters.")[2] The word Muh-he-kan refers to a great sea or body of water, and the Hudson River reminded them of their place of origin, so they named the Hudson River "Seepow Mahecaniittuck," or the river where there are people from the continually flowing waters.[3] Therefore, they, along with other tribes living along the Hudson River (such as the Munsee, known by the dialect of Lenape that they spoke, and Wappinger), were called "the River Indians" by the Dutch and English. The Dutch heard and wrote the term for the people of the area variously as: Mahigan, Mahikander, Mahinganak, Maikan and Mawhickon, which the English simplified later to Mahican or Mohican, in a transliteration to their spelling system. The French, adopting names used by their Indian allies in Canada, knew the Mahican as the Loups (or wolves); similarly, they referred to the Iroquois as the "Snake People" (or "Five Nations"). Like the Munsee and Wappinger peoples, the Mahican were related distantly to the Lenape people, who occupied coastal areas from western Connecticut and western Long Island to the Delaware River valley to the south.

In the late twentieth century, the Mahican joined other former New York tribes and the Oneida in filing land claims against New York state for what were considered unconstitutional purchases after the Revolutionary War. In 2010, outgoing governor David Paterson announced a land exchange with the Stockbridge-Munsee that would enable them to build a large casino on 330 acres (130 ha) in Sullivan County in the Catskills, in exchange for dropping their larger claim in Madison County. The deal had many opponents.

Contents

1 Territory

2 Culture

3 History

3.1 Mahican Confederacy

3.2 Conflict with the Mohawk

3.3 Stockbridge

3.4 Revolutionary War

4 Removal to Wisconsin

5 Land claims

6 Representation in media

7 Notable members

8 References

9 Bibliography

10 External links

Territory

The Mahican were living in and around the Hudson River (or Mahicannituck, their name for it) at the time of their first contact with Europeans traders along the river in the 1590s. After 1609 at the time of the Dutch settlement of New Netherland, they also ranged along the eastern Mohawk River and the Hoosic River. In their own language, the Mahican identified collectively as the Muhhekunneuw', "people of the great river".[4] The Mahican territory was bounded on the northwest by Lake Champlain and Lake George.

Culture

Mahican villages were fairly large. Usually consisting of 20 to 30 mid-sized longhouses, they were located on hills and heavily fortified. Their large cornfields were located nearby. Agriculture and gathering of nuts, fruits and roots provided most of their diet, but was supplemented by the men hunting game, and fishing. Mahican villages were governed by hereditary sachems advised by a council of clan elders. A general council of sachems met regularly at Shodac (east of present-day Albany) to decide important matters affecting the entire confederacy.[4] In his history of the Indians of the Hudson River, Edward Manning Ruttenber described the clans of the Mahicans as the Bear, the Turkey, the Turtle, and the Wolf, with the Wolf serving as a defensive shield in the north against the Mohawk.[citation needed]

History

Mahican Confederacy

The Mahican were a confederacy of five tribes and as many as forty villages.[4]

Mahican proper, (lived in the vicinity of today's Albany (Pempotowwuthut-Muhhcanneuw – "the fireplace of the Mahican Nation") west towards the Mohawk River and to the northwest to Lake Champlain and Lake George)

Mechkentowoon (lived along the west shore of the Hudson River above the Catskill Creek)

Wawyachtonoc (Wawayachtonoc – "eddy people" or "people of the curving channel," lived in Dutchess County and Columbia County eastward to the Housatonic River in Litchfield County, Connecticut, main village was Weantinock, additional villages: Shecomeco, Wechquadnach, Pamperaug, Bantam, Weataug, Scaticook)

Westenhuck (from hous atenuc – "on the other side of the mountains," the name of a village near Great Barrington, Massachusetts. Often called the "Housatonic people," they lived in the Housatonic Valley in Connecticut and Massachusetts and in the vicinity of Great Barrington, which they called Mahaiwe, meaning "the place downstream")[5]

Wiekagjoc (from wikwajek – "upper reaches of a river," lived east of the Hudson Rivers near the city of Hudson, Columbia County, New York)[6]

Conflict with the Mohawk

Land deed, May 31, 1664, Willem Hoffmeyer purchase of 3 islands in the Hudson River near Troy from three native Mahicans - Albany Institute of History and Art

The Algonquians (Mahican) and Iroquois (Mohawk) were traditional competitors and enemies. Iroquois oral tradition, as recorded in the Jesuit Relations, speaks of a war between the Mohawk and an alliance of the Susquehannock and Algonquin (sometime between 1580 and 1600). This was perhaps in response to the formation of the League of the Iroquois.[7]

In September 1609 Henry Hudson encountered Mahican villages just below present day Albany, with whom he traded goods for furs. Hudson returned to Holland with a cargo of valuable furs which immediately attracted Dutch merchants to the area. The first Dutch fur traders arrived on the Hudson River the following year to trade with the Mahican. Besides exposing them to European epidemics, the fur trade destabilized the region.[4]

In 1614, the Dutch decided to establish a permanent trading post on Castle Island, on the site of a previous French post that had been long abandoned; but first they had to arrange a truce to end fighting which had broken out between the Mahican and Mohawk. Fighting broke out again between the Mahican and Mohawk in 1617, and with Fort Nassau badly damaged by a freshet, the Dutch abandoned the fort. In 1618, having once again negotiated a truce, the Dutch rebuilt Fort Nassau on higher ground.[8] Late that year, Fort Nassau was destroyed by flooding and abandoned for good. In 1624, Captain Cornelius Jacobsen May sailed the Nieuw Nederlandt upriver and landed eighteen families of Walloons on a plain opposite Castle Island. They commenced to construct Fort Orange.

The Mahicans invited the Algonquin and Montagnais to bring their furs to Fort Orange as an alternate to French traders in Quebec. Seeing the Mahicans extended their control over the fur trade, the Mohawk attacked, with initial success. In 1625 or 1626 the Mahican destroyed the easternmost Iroquois "castle". The Mohawks then re-located south of the Mohawk River, closer to Fort Orange. In July 1626 many of the settlers moved to New Amsterdam because of the conflict. The Mahicans requested help from the Dutch and Commander Daniel Van Krieckebeek set out from the fort with six soldiers. Van Krieckebeek, three soldiers, and twenty-four Mahicans were killed when their party was ambushed by the Mohawk about mile from the fort. The Mohawks withdrew with some body parts of those slain for later consumption as a demonstration of supremacy.[9]

War continued to rage between the Mahican and Mohawk throughout the area from Skahnéhtati (Schenectady) to Kinderhoek Kinderhook.[10] By 1629, the Mohawk had taken over territories on the west bank of the Hudson River that were formerly held by the Mahican.[11] The conflict caused most of the Mahican to migrate eastward across the Hudson River into western Massachusetts and Connecticut. The Mohawks gained a near-monopoly in the fur trade with the Dutch by prohibiting the nearby Algonquian-speaking tribes to the north or east to trade.

Stockbridge

Many Mahican settled in the town of Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where they gradually became known as the "Stockbridge Indians." Etow Oh Koam, one of their chiefs, accompanied three Mohawk chiefs on a state visit to Queen Anne and her government in England in 1710. They were popularly referred to as the Four Mohawk Kings.

The Mahican chief Etow Oh Koam, referred to as one of the Four Mohawk Kings in a state visit to Queen Anne in 1710. By John Simon, c1750.

The Stockbridge Indians allowed Protestant missionaries, including Jonathan Edwards, to live among them. In the 18th century, many converted to Christianity, while keeping certain traditions of their own. They fought on the side of the British colonists in the French and Indian War (also known as the Seven Years' War). During the American Revolution, they sided with the colonists.[12]

In the eighteenth century, some of the Mahican developed strong ties with missionaries of the Moravian Church from Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, who founded a mission at their village of Shekomeko in Dutchess County, New York. Henry Rauch reached out to two Mahican leaders, Maumauntissekun, also known as Shabash; and Wassamapah, who took him back to Shekomeko. They named him the new religious teacher. Over time, Rauch won listeners, as the Mahicans had suffered much from disease and warfare, which had disrupted their society. Early in 1742, Shabash and two other Mahican accompanied Rauch to Bethlehem, where he was to be ordained as a deacon. The three Mahicans were baptized on February 11, 1742 in John de Turk's barn nearby at Oley, Pennsylvania. Shabash was the first Mahican of Shekomeko to adopt the Christian religion.[13] The Moravians built a chapel for the Mahican people in 1743. They defended the Mahican against European settlers' exploitation, trying to protect them against land encroachment and abuses of liquor.

On a 1738 visit to New York, the Mahican spoke to the Governor Lewis Morris concerning the sale of their land near Shekomeko. The Governor promised they would be paid as soon as the lands were surveyed. He suggested that for their own security, they should mark off their square mile of land they wished to keep, which the Mahican never did. In September 1743, still under the Acting-Governor George Clarke the land was finally surveyed by New York Assembly agents and divided into lots, a row of which ran through the Indians' reserved land. With some help from the missionaries, on October 17, 1743 and already under the new Royal Governor George Clinton, Shabash put together a petition of names of people who could attest that the land in which one of the lots was running through was theirs. Despite Shabash's appeals, his persistence, and the missionaries' help, the Mahican lost the case.[14] The lots were eventually bought up by European-American settlers and the Mahican were forced out of Shekomeko. Some who opposed the missionaries' work accused them of being secret Catholic Jesuits (who had been outlawed from the colony in 1700) and of working with the Mahican on the side of the French. The missionaries were summoned more than once before colonial government, but also had supporters. In the late 1740s the colonial government at Poughkeepsie expelled the missionaries from New York, in part because of their advocacy of Mahican rights. Settlers soon took over the Mahican land.[15]

Revolutionary War

Von Ewald sketch of a Stockbridge Militia Mahican warrior who fought on the Patriot side in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War

In August 1775, the Six Nations staged a council fire near Albany, after news of Bunker Hill had made war seem imminent. After much debate, they decided that such a war was a private affair between the British and the colonists (known as Rebels, Revolutionaries, Congress-Men, American Whigs, or Patriots), and that they should stay out of it. Mohawk Chief Joseph Brant feared that the Indians would lose their lands if the Colonists achieved independence. Sir William Johnson, his son John Johnson and son-in-law Guy Johnson and Brant used all their influence to engage the Iroquois to fight for the British cause. The Mohawk, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca ultimately became allies and provided warriors for the battles in the New York area. The Oneida and Tuscarora sided with the Colonists. The Mahican, who as Algonquians were not part of the Iroquois Confederacy, sided with the Patriots, serving at the Siege of Boston, and the battles of Saratoga and Monmouth.

In 1778 they lost fifteen warriors in a British ambush at the Bronx, New York, and later received a commendation from George Washington.[16]

Later, the citizens of the new United States forced many Native Americans off their land and westward. In the 1780s, groups of Stockbridge Indians moved from Massachusetts to a new location among the Oneida people in western New York, who were granted a 300,000-acre (120,000 ha) reservation for their service to the Patriots, out of their former territory of 6,000,000 acres (2,400,000 ha). They called their settlement New Stockbridge. Some individuals and families, mostly people who were old or those with special ties to the area, remained behind at Stockbridge.

The central figures of Mahican society, including the chief sachem, Joseph Quanaukaunt, and his counselors and relatives, were part of the move to New Stockbridge. At the new town, the Stockbridge emigrants controlled their own affairs and combined traditional ways with the new as they chose. After learning from the Christian missionaries, the Stockbridge Indians were experienced in English ways. At New Stockbridge they replicated their former town. While continuing as Christians, they retained their language and Mahican cultural traditions. In general, their evolving Mahican identity was still rooted in traditions of the past.[17]

Removal to Wisconsin

In the 1820s and 1830s, most of the Stockbridge Indians moved to Shawano County, Wisconsin, where they were promised land by the US government under the policy of Indian removal. In Wisconsin, they settled on reservations with the Lenape (called Munsee after one of their major dialects), who were also speakers of one of the Algonquian languages. Together, the two formed a band and are federally recognized as the Stockbridge-Munsee Community.

The now extinct Mahican language belonged to the Eastern Algonquian branch of the Algonquian language family. It was an Algonquian N-dialect, as were Massachusett and Wampanoag. In many ways, it was similar to one of the L-dialects, like that of the Lenape, and could be considered one.

Their 22,000-acre reservation is known as that of the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians and is located near the town of Bowler. Since the late twentieth century, they have developed the North Star Mohican Resort and Casino on their reservation, which has successfully generated funds for tribal welfare and economic development.[18]

Land claims

In the late twentieth century, the Stockbridge-Munsee were among tribes filing land claims against New York, which had been ruled to have unconstitutionally acquired land from Indians without Senate ratification. The Stockbridge-Munsee filed a land claim against New York state for 23,000 acres (9,300 ha) in Madison County, the location of its former property. In 2011, outgoing governor David Paterson announced having reached a deal with the tribe. They would be given nearly 2 acres (0.81 ha) in Madison County and give up their larger claim in exchange for the state's giving them 330 acres of land in Sullivan County in the Catskill Mountains, where the government was trying to encourage economic development. The federal government had agreed to take the land in trust, making it eligible for development as a gaming casino, and the state would allow gaming, an increasingly important source of revenue for American Indians. Race track and casinos, private interests and other tribes opposed the deal.[18]

Representation in media

James Fenimore Cooper based his novel, The Last of the Mohicans, on the Mahican tribe. His description includes some cultural aspects of the Mohegan, a different Algonquian tribe that lived in eastern Connecticut. Cooper set his novel in the Hudson Valley, Mahican land, but used some Mohegan names for his characters, such as Uncas.

The novel has been adapted for the cinema more than a dozen times, the first time in 1920. Michael Mann directed a 1992 adaptation, which starred Daniel Day-Lewis as a Mohican-adopted white man.

Notable members

Hendrick Aupaumut, (1757-1830) sachem, historian, and American Revolutionary War captain

Brent Michael Davids, (b. 1959) composer/flautist

Anthony Kiedis, (b. 1962) singer for Red Hot Chili Peppers

Bill Miller, (b. 1955) musician

Electa Quinney, (1798-1885) first public teacher and school mistress in Wisconsin

John Wannuaucon Quinney, (1797-1855) diplomat

References

^ EB-Mohicans "Mohican" (history), Encyclopædia Britannica, 2007[dead link]

^ Stockbridge, Past and Present; Electa Jones

^ "Mohican Oral Tribal History as recorded by Hendrick Aupaumut" and printed in Stockbridge, Past and Present by Electa Jones.

^ abcd Sultzman, Lee. "Mahican History"

^ Donald B. Ricky: Indians of Maryland Past and Present, Verlag: Somerset Pubs, 1999; .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 978-0403098774

^ Allen W. Trelease, William A. Starna: Indian Affairs in Colonial New York Indian Affairs in Colonial New York: The Seventeenth Century the Seventeenth Century, Seite 8, University of Nebraska Press; 1997,

ISBN 978-0803294318

^ Brandon, William. American Heritage Book of Indians, (Alvin M. Josephy, ed.), American Heritage Pub. Co. 1961, p. 187

^ "Mahican Confederacy", The History Files

^ Parmenter, Jon W., "Separate Vessels", The Worlds of the Seventeenth-Century Hudson Valley, (Jaap Jacobs, L. H. Roper, eds.) SUNY Press, 2014, ISBN 9781438450971 p. 113

^ Reynolds, Cuyler. Albany Chronicles: A History of the City Arranged Chronologically, J.B. Lyon Company, 1906 This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

^ Burke Jr, T. E., & Starna, W. A. (1991). Mohawk Frontier: The Dutch Community of Schenectady, New York, 1661–1710, SUNY Press. p. 26

^ Calloway, Colin (1995). The American Revolution in Indian Country: Crisis and Diversity in Native American Communities. Cambridge University Press. pp. 88–107. ISBN 978-0-521-47149-7.

^ Dunn (2000). The Mohican World 1680-1750. pp. 228–230.

^ Dunn (2000). The Mohican World 1680-1750. pp. 232–235.

^ PHILIP H. SMITH, "PINE PLAINS", GENERAL HISTORY OF DUCHESS COUNTY FROM 1609 TO 1876, INCLUSIVE, PAWLING, NY: 1877, accessed 3 March 2010

^ Aupaumut, Hendrick. "From George Washington to Captain Hendrick Aupaumut, 4 July 1779". Archives.gov.

^ Dunn, Shirley (2000). The Mohican World 1680-1750. Fleischmanns, New York: Purple Mountain Press, Ltd. p. 213.

^ ab Gale Courey Toensing, "Seneca Upset Over N.Y. Casino Agreement", Indian Country Today, 26 January 2011

Bibliography

- Aupaumut, Hendrick. (1790). "History of the Muh-he-con-nuk Indians", in American Indian Nonfiction, An Anthology of Writings, 1760s-1930s (pp. 63-71). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Brasser, T. J. (1978). "Mahican", in B. G. Trigger (Ed.), Northeast (pp. 198–212). Handbook of North American Indian languages (Vol. 15). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Cappel, Constance, "The Smallpox Genocide of the Odawa Tribe at L'Arbre Croche, 1763", The History of a Native American People, Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2007.

- Conkey, Laura E.; Bolissevain, Ethel; & Goddard, Ives. (1978). "Indians of southern New England and Long Island: Late period", in B. G. Trigger (Ed.), Northeast (pp. 177–189). Handbook of North American Indian languages (Vol. 15). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Ruttenber, E. M. (1872). "History of the Indian Tribes of Hudson's River; Their Origin, Manners and Customs; Tribal and Sub-Tribal Organizations; Wars, Treaties, Etc., Etc." Albany: J. Munsell History Series.

- Salwen, Bert. (1978). "Indians of southern New England and Long Island: Early period", in B. G. Trigger (Ed.), Northeast (pp. 160–176). Handbook of North American Indian languages (Vol. 15). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Simpson, J. A.; & Weiner, E. S. C. (1989). "Mohican", Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press. (Online version).

- Sturtevant, William C. (Ed.). (1978–present). Handbook of North American Indians (Vol. 1-20). Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Trigger, Bruce G. (Ed.). (1978). Northeast, Handbook of North American Indians (Vol. 15). Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- William A. Starna: From Homeland to New Land: A History of the Mahican Indians, 1600-1830. University of Nebraska Press, 2013.

ISBN 978-0803244955

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mahican. |

- Stockbridge-Munsee community

- Mohican nation Stockbridge-Munsee band: Our history

- Mohican Indians

GYNnsT2Zk P