Arc length

Arc length s of a logarithmic spiral as a function of its parameter θ.

Arc length is the distance between two points along a section of a curve.

Determining the length of an irregular arc segment is also called rectification of a curve. The advent of infinitesimal calculus led to a general formula that provides closed-form solutions in some cases.

Contents

1 General approach

2 Definition for a smooth curve

3 Finding arc lengths by integrating

3.1 Numerical integration

3.2 Curve on a surface

3.3 Other coordinate systems

4 Simple cases

4.1 Arcs of circles

4.1.1 Arcs of great circles on the Earth

4.2 Length of an arc of a parabola

5 Historical methods

5.1 Antiquity

5.2 17th century

5.3 Integral form

6 Curves with infinite length

7 Generalization to (pseudo-)Riemannian manifolds

8 See also

9 References

10 Sources

11 External links

General approach

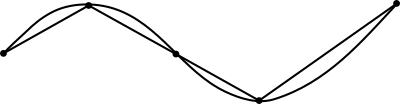

Approximation by multiple linear segments

A curve in the plane can be approximated by connecting a finite number of points on the curve using line segments to create a polygonal path. Since it is straightforward to calculate the length of each linear segment (using the Pythagorean theorem in Euclidean space, for example), the total length of the approximation can be found by summing the lengths of each linear segment; that approximation is known as the (cumulative) chordal distance.[1]

If the curve is not already a polygonal path, using a progressively larger number of segments of smaller lengths will result in better approximations. The lengths of the successive approximations will not decrease and may keep increasing indefinitely, but for smooth curves they will tend to a finite limit as the lengths of the segments get arbitrarily small.

For some curves there is a smallest number L{displaystyle L}

Definition for a smooth curve

Let f:[a,b]→Rn{displaystyle fcolon [a,b]to mathbb {R} ^{n}}![{displaystyle fcolon [a,b]to mathbb {R} ^{n}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4384ee07c2e449e026d0e76da4d1dce99f3658cd)

![[a,b]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935)

- L(f)=limN→∞∑i=1N|f(ti)−f(ti−1)|{displaystyle L(f)=lim _{Nto infty }sum _{i=1}^{N}{bigg |}f(t_{i})-f(t_{i-1}){bigg |}}

where ti=a+i(b−a)/N=a+iΔt{displaystyle t_{i}=a+i(b-a)/N=a+iDelta t}

- limN→∞∑i=1N|f(ti)−f(ti−1)|=limN→∞∑i=1N|f(ti)−f(ti−1)Δt|Δt=∫ab|f′(t)| dt.{displaystyle lim _{Nto infty }sum _{i=1}^{N}{bigg |}f(t_{i})-f(t_{i-1}){bigg |}=lim _{Nto infty }sum _{i=1}^{N}left|{frac {f(t_{i})-f(t_{i-1})}{Delta t}}right|Delta t=int _{a}^{b}{Big |}f'(t){Big |} dt.}

The last equality above is true because the definition of the derivative as a limit implies that there is a positive real function δ(ϵ){displaystyle delta (epsilon )}

- ∑i=1N|f(ti)−f(ti−1)Δt|Δt−∑i=1N|f′(ti)|Δt{displaystyle sum _{i=1}^{N}left|{frac {f(t_{i})-f(t_{i-1})}{Delta t}}right|Delta t-sum _{i=1}^{N}{Big |}f'(t_{i}){Big |}Delta t}

has absolute value less than ϵ(b−a){displaystyle epsilon (b-a)}

![{displaystyle [a,b].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3ba5cb29655f824ce80a0b6a32d9326d0e8742cd)

![{displaystyle f:[a,b]rightarrow mathbb {R} ^{n}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1d8ca3f3131426f0afe87c34b8178f297bd23f2b)

![[a,b]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935)

The definition of arc length of a smooth curve as the integral of the norm of the derivative is equivalent to the definition

- L(f)=sup∑i=1N|f(ti)−f(ti−1)|{displaystyle L(f)=sup sum _{i=1}^{N}{bigg |}f(t_{i})-f(t_{i-1}){bigg |}}

where the supremum is taken over all possible partitions a=t0<t1<⋯<tN−1<tN=b{displaystyle a=t_{0}<t_{1}<dots <t_{N-1}<t_{N}=b}

![{displaystyle [a,b].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3ba5cb29655f824ce80a0b6a32d9326d0e8742cd)

A curve can be parameterized in infinitely many ways. Let φ:[a,b]→[c,d]{displaystyle varphi :[a,b]to [c,d]}![{displaystyle varphi :[a,b]to [c,d]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3293091d7865361d0748a12bbb33ea442e32ba87)

![{displaystyle g=fcirc varphi ^{-1}:[c,d]to mathbb {R} ^{n}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cf785b379b7ae9d54bdbc6c626151ae0a0210818)

- L(f)=∫ab|f′(t)| dt=∫ab|g′(φ(t))φ′(t)| dt=∫ab|g′(φ(t))|φ′(t) dtsince φ must be non-decreasing=∫cd|g′(u)| duusing integration by substitution=L(g).{displaystyle {begin{aligned}L(f)&=int _{a}^{b}{Big |}f'(t){Big |} dt=int _{a}^{b}{Big |}g'(varphi (t))varphi '(t){Big |} dt\&=int _{a}^{b}{Big |}g'(varphi (t)){Big |}varphi '(t) dtquad {textrm {since}} varphi {textrm {must}} {textrm {be}} {textrm {non-decreasing}}\&=int _{c}^{d}{Big |}g'(u){Big |} duquad {textrm {using}} {textrm {integration}} {textrm {by}} {textrm {substitution}}\&=L(g).end{aligned}}}

Finding arc lengths by integrating

Quarter circle

If a planar curve in R2{displaystyle mathbb {R} ^{2}}

- s=∫ab1+(dydx)2dx.{displaystyle s=int _{a}^{b}{sqrt {1+left({frac {dy}{dx}}right)^{2}}}dx.}

Curves with closed-form solutions for arc length include the catenary, circle, cycloid, logarithmic spiral, parabola, semicubical parabola and straight line. The lack of a closed form solution for the arc length of an elliptic arc led to the development of the elliptic integrals.

Numerical integration

In most cases, including even simple curves, there are no closed-form solutions for arc length and numerical integration is necessary. Numerical integration of the arc length integral is usually very efficient. For example, consider the problem of finding the length of a quarter of the unit circle by numerically integrating the arc length integral. The upper half of the unit circle can be parameterized as y=1−x2.{displaystyle y={sqrt {1-x^{2}}}.}

![{displaystyle xin [-{sqrt {2}}/2,{sqrt {2}}/2]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2d068143977ed8e9ac6792c86d0157adf47eefd1)

- ∫−2/22/211−x2dx.{displaystyle int _{-{sqrt {2}}/2}^{{sqrt {2}}/2}{frac {1}{sqrt {1-x^{2}}}}dx.}

The 15-point Gauss-Kronrod rule estimate for this integral of 7000157079632680817♠1.570796326808177 differs from the true length of π/2{displaystyle pi /2}

Curve on a surface

Let x(u,v){displaystyle mathbf {x} (u,v)}

- D(x∘C)=(xu xv)(u′v′)=xuu′+xvv′.{displaystyle D(mathbf {x} circ mathbf {C} )=(mathbf {x} _{u} mathbf {x} _{v}){binom {u'}{v'}}=mathbf {x} _{u}u'+mathbf {x} _{v}v'.}

The squared norm of this vector is (xuu′+xvv′)⋅(xuu′+xvv′)=g11(u′)2+2g12u′v′+g22(v′)2{displaystyle (mathbf {x} _{u}u'+mathbf {x} _{v}v')cdot (mathbf {x} _{u}u'+mathbf {x} _{v}v')=g_{11}(u')^{2}+2g_{12}u'v'+g_{22}(v')^{2}}

Other coordinate systems

Let C(t)=(r(t),θ(t)){displaystyle mathbf {C} (t)=(r(t),theta (t))}

- x(r,θ)=(rcosθ,rsinθ).{displaystyle mathbf {x} (r,theta )=(rcos theta ,rsin theta ).}

The integrand of the arc length integral is |(x∘C)′(t)|.{displaystyle |(mathbf {x} circ mathbf {C} )'(t)|.}

- (xr⋅xr)(r′)2+2(xr⋅xθ)r′θ′+(xθ⋅xθ)(θ′)2=(r′)2+r2(θ′)2.{displaystyle (mathbf {x_{r}} cdot mathbf {x} _{r})(r')^{2}+2(mathbf {x} _{r}cdot mathbf {x} _{theta })r'theta '+(mathbf {x} _{theta }cdot mathbf {x} _{theta })(theta ')^{2}=(r')^{2}+r^{2}(theta ')^{2}.}

So for a curve expressed in polar coordinates, the arc length is

- ∫t1t2(drdt)2+r2(dθdt)2dt=∫θ(t1)θ(t2)(drdθ)2+r2dθ.{displaystyle int _{t_{1}}^{t_{2}}{sqrt {left({frac {dr}{dt}}right)^{2}+r^{2}left({frac {dtheta }{dt}}right)^{2}}}dt=int _{theta (t_{1})}^{theta (t_{2})}{sqrt {left({frac {dr}{dtheta }}right)^{2}+r^{2}}}dtheta .}

Now let C(t)=(r(t),θ(t),ϕ(t)){displaystyle mathbf {C} (t)=(r(t),theta (t),phi (t))}

- x(r,θ,ϕ)=(rsinθcosϕ,rsinθsinϕ,rcosθ).{displaystyle mathbf {x} (r,theta ,phi )=(rsin theta cos phi ,rsin theta sin phi ,rcos theta ).}

Using the chain rule again shows that D(x∘C)=xrr′+xθθ′+xϕϕ′.{displaystyle D(mathbf {x} circ mathbf {C} )=mathbf {x} _{r}r'+mathbf {x} _{theta }theta '+mathbf {x} _{phi }phi '.}

- (xr⋅xr)(r′2)+(xθ⋅xθ)(θ′)2+(xϕ⋅xϕ)(ϕ′)2=(r′)2+r2(θ′)2+r2sin2θ(ϕ′)2.{displaystyle (mathbf {x} _{r}cdot mathbf {x} _{r})(r'^{2})+(mathbf {x} _{theta }cdot mathbf {x} _{theta })(theta ')^{2}+(mathbf {x} _{phi }cdot mathbf {x} _{phi })(phi ')^{2}=(r')^{2}+r^{2}(theta ')^{2}+r^{2}sin ^{2}theta (phi ')^{2}.}

So for a curve expressed in spherical coordinates, the arc length is

- ∫t1t2(drdt)2+r2(dθdt)2+r2sin2θ(dϕdt)2dt.{displaystyle int _{t_{1}}^{t_{2}}{sqrt {left({frac {dr}{dt}}right)^{2}+r^{2}left({frac {dtheta }{dt}}right)^{2}+r^{2}sin ^{2}theta left({frac {dphi }{dt}}right)^{2}}}dt.}

A very similar calculation shows that the arc length of a curve expressed in cylindrical coordinates is

- ∫t1t2(drdt)2+r2(dθdt)2+(dzdt)2dt.{displaystyle int _{t_{1}}^{t_{2}}{sqrt {left({frac {dr}{dt}}right)^{2}+r^{2}left({frac {dtheta }{dt}}right)^{2}+left({frac {dz}{dt}}right)^{2}}}dt.}

Simple cases

Arcs of circles

Arc lengths are denoted by s, since the Latin word for length (or size) is spatium.

In the following lines, r{displaystyle r}

C=2πr,{displaystyle C=2pi r,}which is the same as C=πd.{displaystyle C=pi d.}

This equation is a definition of π.{displaystyle pi .}

- If the arc is a semicircle, then s=πr.{displaystyle s=pi r.}

For an arbitrary circular arc:

- If θ{displaystyle theta }

is in radians then s=rθ.{displaystyle s=rtheta .}

This is a definition of the radian.

- If θ{displaystyle theta }

is in degrees, then s=πrθ180,{displaystyle s={frac {pi rtheta }{180}},}

which is the same as s=Cθ360.{displaystyle s={frac {Ctheta }{360}}.}

- If θ{displaystyle theta }

is in grads (100 grads, or grades, or gradians are one right-angle), then s=πrθ200,{displaystyle s={frac {pi rtheta }{200}},}

which is the same as s=Cθ400.{displaystyle s={frac {Ctheta }{400}}.}

- If θ{displaystyle theta }

is in turns (one turn is a complete rotation, or 360°, or 400 grads, or 2π{displaystyle 2pi }

radians), then s=Cθ.{displaystyle s=Ctheta .}

- If θ{displaystyle theta }

Arcs of great circles on the Earth

Two units of length, the nautical mile and the metre (or kilometre), were originally defined so the lengths of arcs of great circles on the Earth's surface would be simply numerically related to the angles they subtend at its centre. The simple equation s=θ{displaystyle s=theta }

- if s{displaystyle s}

is in nautical miles, and θ{displaystyle theta }

is in arcminutes (1⁄60 degree), or

- if s{displaystyle s}

is in kilometres, and θ{displaystyle theta }

is in centigrades (1⁄100 grad).

- if s{displaystyle s}

The lengths of the distance units were chosen to make the circumference of the Earth equal 7004400000000000000♠40000 kilometres, or 7004216000000000000♠21600 nautical miles. Those are the numbers of the corresponding angle units in one complete turn.

Those definitions of the metre and the nautical mile have been superseded by more precise ones, but the original definitions are still accurate enough for conceptual purposes and some calculations. For example, they imply that one kilometre is exactly 0.54 nautical miles. Using official modern definitions, one nautical mile is exactly 1.852 kilometres,[3] which implies that 1 kilometre is about 6999539956800000000♠0.53995680 nautical miles.[4] This modern ratio differs from the one calculated from the original definitions by less than one part in 10,000.

Length of an arc of a parabola

Historical methods

Antiquity

For much of the history of mathematics, even the greatest thinkers considered it impossible to compute the length of an irregular arc. Although Archimedes had pioneered a way of finding the area beneath a curve with his "method of exhaustion", few believed it was even possible for curves to have definite lengths, as do straight lines. The first ground was broken in this field, as it often has been in calculus, by approximation. People began to inscribe polygons within the curves and compute the length of the sides for a somewhat accurate measurement of the length. By using more segments, and by decreasing the length of each segment, they were able to obtain a more and more accurate approximation. In particular, by inscribing a polygon of many sides in a circle, they were able to find approximate values of π.[5][6]

17th century

In the 17th century, the method of exhaustion led to the rectification by geometrical methods of several transcendental curves: the logarithmic spiral by Evangelista Torricelli in 1645 (some sources say John Wallis in the 1650s), the cycloid by Christopher Wren in 1658, and the catenary by Gottfried Leibniz in 1691.

In 1659, Wallis credited William Neile's discovery of the first rectification of a nontrivial algebraic curve, the semicubical parabola.[7] The accompanying figures appear on page 145. On page 91, William Neile is mentioned as Gulielmus Nelius.

Integral form

Before the full formal development of calculus, the basis for the modern integral form for arc length was independently discovered by Hendrik van Heuraet and Pierre de Fermat.

In 1659 van Heuraet published a construction showing that the problem of determining arc length could be transformed into the problem of determining the area under a curve (i.e., an integral). As an example of his method, he determined the arc length of a semicubical parabola, which required finding the area under a parabola.[8] In 1660, Fermat published a more general theory containing the same result in his De linearum curvarum cum lineis rectis comparatione dissertatio geometrica (Geometric dissertation on curved lines in comparison with straight lines).[9]

Fermat's method of determining arc length

Building on his previous work with tangents, Fermat used the curve

- y=x3/2{displaystyle y=x^{3/2},}

whose tangent at x = a had a slope of

- 32a1/2{displaystyle textstyle {3 over 2}a^{1/2}}

so the tangent line would have the equation

- y=32a1/2(x−a)+f(a).{displaystyle y=textstyle {3 over 2}{a^{1/2}}(x-a)+f(a).}

Next, he increased a by a small amount to a + ε, making segment AC a relatively good approximation for the length of the curve from A to D. To find the length of the segment AC, he used the Pythagorean theorem:

- AC2=AB2+BC2=ε2+94aε2=ε2(1+94a){displaystyle {begin{aligned}AC^{2}&{}=AB^{2}+BC^{2}\&{}=textstyle varepsilon ^{2}+{9 over 4}avarepsilon ^{2}\&{}=textstyle varepsilon ^{2}left(1+{9 over 4}aright)end{aligned}}}

which, when solved, yields

- AC=ε1+94a .{displaystyle AC=textstyle varepsilon {sqrt {1+{9 over 4}a }}.}

In order to approximate the length, Fermat would sum up a sequence of short segments.

Curves with infinite length

The Koch curve.

The graph of xsin(1/x).

As mentioned above, some curves are non-rectifiable. That is, there is no upper bound on the lengths of polygonal approximations; the length can be made arbitrarily large. Informally, such curves are said to have infinite length. There are continuous curves on which every arc (other than a single-point arc) has infinite length. An example of such a curve is the Koch curve. Another example of a curve with infinite length is the graph of the function defined by f(x) = x sin(1/x) for any open set with 0 as one of its delimiters and f(0) = 0. Sometimes the Hausdorff dimension and Hausdorff measure are used to quantify the size of such curves.

Generalization to (pseudo-)Riemannian manifolds

Let M{displaystyle M}

![{displaystyle gamma :[0,1]rightarrow M}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e4f535d796622749b40699d49c3dfea3ce1c4907)

The length of γ{displaystyle gamma }

- ℓ(γ)=∫01±g(γ′(t),γ′(t))dt,{displaystyle ell (gamma )=int _{0}^{1}{sqrt {pm g(gamma '(t),gamma '(t))}},dt,}

where γ′(t)∈Tγ(t)M{displaystyle gamma '(t)in T_{gamma (t)}M}

In theory of relativity, arc length of timelike curves (world lines) is the proper time elapsed along the world line, and arc length of a spacelike curve the proper distance along the curve.

See also

- Arc (geometry)

- Circumference

- Crofton formula

- Elliptic integral

- Geodesics

- Intrinsic equation

- Integral approximations

- Line integral

- Meridian arc

- Multivariable calculus

- Sinuosity

References

^ Ahlberg; Nilson (1967). The Theory of Splines and Their Applications. Academic Press. p. 51. ISBN 9780080955452..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Rudin, Walter (1976). Principles of Mathematical Analysis. McGraw-Hill, Inc. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-07-054235-8.

^ Suplee, Curt (2 July 2009). "Special Publication 811". nist.gov.

^ CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, p. F-254

^ Richeson, David (May 2015). "Circular Reasoning: Who First Proved That C Divided by d Is a Constant?". The College Mathematics Journal. 46 (3): 162–171. doi:10.4169/college.math.j.46.3.162. ISSN 0746-8342.

^ Coolidge, J. L. (February 1953). "The Lengths of Curves". The American Mathematical Monthly. 60 (2): 89–93. doi:10.2307/2308256. JSTOR 2308256.

^ Wallis, John (1659). Tractatus Duo. Prior, De Cycloide et de Corporibus inde Genitis…. Oxford: University Press. pp. 91–96.

^ van Heuraet, Hendrik (1659). "Epistola de transmutatione curvarum linearum in rectas [Letter on the transformation of curved lines into right ones]". Renati Des-Cartes Geometria (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Louis & Daniel Elzevir. pp. 517–520.

^ M.P.E.A.S. (pseudonym of Fermat) (1660). De Linearum Curvarum cum Lineis Rectis Comparatione Dissertatio Geometrica. Toulouse: Arnaud Colomer.

Sources

Farouki, Rida T. (1999). "Curves from motion, motion from curves". In Laurent, P.-J.; Sablonniere, P.; Schumaker, L. L. Curve and Surface Design: Saint-Malo 1999. Vanderbilt Univ. Press. pp. 63–90. ISBN 978-0-8265-1356-4.

External links

Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001) [1994], "Rectifiable curve", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- The History of Curvature

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Arc Length". MathWorld.

Arc Length by Ed Pegg, Jr., The Wolfram Demonstrations Project, 2007.

[permanent dead link] Calculus Study Guide – Arc Length (Rectification)

Famous Curves Index The MacTutor History of Mathematics archive

Arc Length Approximation by Chad Pierson, Josh Fritz, and Angela Sharp, The Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

Length of a Curve Experiment Illustrates numerical solution of finding length of a curve.