Carvel (boat building)

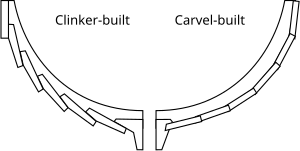

A comparison of clinker and carvel construction. Carvel frames are much heavier than clinker ribs.

Carvel built or carvel planking is a method of boat building where hull planks are laid edge to edge and fastened to a robust frame, thereby forming a smooth surface. Traditionally the planks are neither attached to, nor slotted into, each other, having only a caulking sealant between the planks to keep water out. Modern carvel builders may attach the planks to each other with glues and fixings.[1]

Contents

1 History

1.1 Relationship between clinker and carvel

1.2 Linen build

1.3 Modern carvel methods

1.4 Cold moulding

2 References

History

The Danish Bronze Age ship, Hjortspring, is the earliest evidence for clinker construction in Northern Europe dating to the 4th century BC. The most well-known examples of this construction type are attributed to the Vikings with ships like the Oseburg, Gokstad, The Roskilde viking ships and the Schlie fjord wrecks, just to name a few. [2][3] Carvel building was one of the critical developments that led to the pre-eminence of Western European seapower during the Age of Sail and beyond.[citation needed] Carvel construction developed from the age-old Mediterranean mortise and tenon joint method to the skeleton-first hull building technique, which gradually emerged in the medieval period.[citation needed] The first large carvel-built ships were carracks and caravels of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, developed in Iberia and commissioned by the kingdoms of Portugal and Spain in the trans-oceanic voyages of the Age of Discovery.[clarification needed] The conflict between Christians and Muslims in Iberia was swinging to the Christian side, represented by the Kingdoms of Aragon and Castile (later united as Spain, around the time of Christopher Columbus). The invention of carvel is generally credited to the Portuguese who were the first to explore the Atlantic islands. These navigators sailed further south along the coast of Africa, searching for a trade route to the Far East to avoid the costly middlemen of the Eastern Mediterranean civilizations which controlled the land routes of the spice trade. Spices, in the era, were expensive luxuries and were used medicinally.

Relationship between clinker and carvel

Clinker was the predominant method of ship construction used in Northern Europe before the carvel. In clinker built hulls, the planked edges overlap; carvel construction with its strong framing gives a heavier but more rigid hull, capable of taking a variety of sail rigs. Clinker (lapstrake) construction involves longitudinal overlapping "riven timber" (split wood) planks that are fixed together over very light scantlings. A carvel boat has a smoother surface which gives the impression that it is more hydrodynamically efficient since the exposed edges of the clinker planking appear to disturb the streamline and cause drag. A clinker certainly has a slightly larger wetted area, but a carvel hull is not necessarily more efficient: for given hull strength, the clinker boat is lighter overall, so displaces less water than a heavily-framed carvel hull.

As cargo vessels become bigger, the vessel's weight becomes small in comparison with total displacement; and for a given external volume, there is greater internal hull space available. A clinker vessel whose ribs occupy less space than a carvel vessel's is more suitable for cargos which are bulky rather than dense.

A structural benefit of clinker construction is that it produces a vessel that can safely twist and flex around its long axis (running from bow to stern). This is an advantage in North Atlantic rollers provided the vessel has a small overall displacement. Due to the light nature of the construction method, increasing the beam did not commensurately increase the vessel's survivability under the twisting forces arising if, for example, when sailing downwind, the wave-train impinges on the quarter rather than dead astern.[clarification needed] In these conditions greater beam widths may have made vessels[which?] more vulnerable. As torsional forces grew in proportion to displaced (or cargo) weight, the physics imposed an upper limit on the size of clinker-built vessels. The greater rigidity of carvel construction became necessary for larger offshore cargo vessels. Later carvel-built sailing vessels exceeded the maximum size of clinker-built ships several times over.

A further clinker limitation is that it does not readily support the point loads associated with lateen or sloop sailing rigs. At least some fore-and-aft sails are desirable for manoeuvrability. The same problem in providing for concentrated loads makes for difficulties siting and supporting a centerboard or deep keel, much needed when sailing across or close to the wind. Timbers can be added as necessary compromise but always with some loss of the fundamental benefits of the construction method. Clinker construction remains a useful method of construction for small wooden vessels, especially sea-going dinghies which need to be light enough to be readily moved and stored when out of the water.

Linen build

A development of carvel in the 19th century was linen build. Here, instead of a single thickness of hull planks, there would be two thinner layers. The inner monocoque hull would be built, and before the outer layer of planks was applied, the inner hull would be covered with a layer of linen sheeting glued in place. The second hull would be adhered to the linen, with the new planks at an angle to the first. This rather modern approach provided a much stiffer and stronger hull, provided that the caulking could keep the water out and prevent deterioration of the linen and the adhesive. Linen build was perhaps a precursor of cold moulding (below).

Modern carvel methods

Traditional carvel methods leave a small gap between each plank that is caulked with any suitable soft, flexible, fibrous material, sometimes combined with a thick binding substance, which would gradually wear out and the hull would leak. When the boat was beached for a length of time, the planks would dry and shrink, so when first refloated, the hull would leak badly unless re-caulked, a time-consuming and physically demanding job. The modern variation is to use much narrower planks that are edge-glued instead of being caulked. With modern power sanders a much smoother hull is produced, as all the small ridges between the planks can be removed. This method started to become more common in the 1960s with the more widespread availability of waterproof glues, such as resorcinol (red glue) and then epoxy resin.[4] Modern waterproof glues, especially epoxy resin, have caused revolutionary changes in carvel and clinker construction. Traditionally, nails provided the fastening strength, now it is the glue. It has become quite common since the 1980s for carvel and clinker construction to rely almost completely on glue for fastening. Many small boats, especially light plywood skiffs, are built without any mechanical fasteners such as nails and lag screws at all, as the glue is far stronger.

Cold moulding

A further modern development of carvel is cold moulding or strip-planking. The latter is used for small boats and kayaks, where the hull is made up of narrow strips of wood built up on a wooden jig and glued together. Larger vessels may have two or three layers of strips which (being a pre-shaped marine ply), forms a light, strong and torsionally stiff monocoque which need little or no framing. The cold moulded hull may have an epoxy sheathing (both on the outside and inside) for durability and to be watertight. The epoxy may be clear (to show off the beauty of the wood) or coloured and it may be reinforced with Fiberglass.

References

^ Carvel Planking Texts for Sailboats—Richard Joyce Montana Tech

^ Haywood, John (2006). Dark Age Naval Power: Frankish & Anglo-Saxon Seafaring Activity. Routledge. p. 18. ISBN 978-1898281436..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Jan, Bill (2003). "SCANDINAVIAN WARSHIPS AND NAVAL POWER IN THE THIRTEENTH AND FOURTEENTH CENTURIES". War at Sea in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. 14: 35–52. doi:10.7722/j.ctt81rtx.9 (inactive 2019-03-09). JSTOR 10.7722/j.ctt81rtx.9 – via JSTOR.

^ West System International http://www.westsysteminternational.com/en/welcome/an-illustrated-history