Ragnar Lodbrok

Lothbrocus and his sons Ivar and Ubba. 15th century miniature in Harley MS 2278, folio 39r.

Ragnar Lodbrok or Lothbrok (Old Norse: Ragnarr Loþbrók, "Ragnar shaggy breeches", contemporary Icelandic: Ragnar Loðbrók) is a legendary[1][2] Swedish[3]Viking hero and ruler, known from Viking Age Old Norse poetry and sagas. According to that traditional literature, Ragnar distinguished himself by many raids against Francia and Anglo-Saxon England during the 9th century. There is no known evidence to substantiate that he actually existed under this name and outside of the mythology associated with him.

Contents

1 The Viking Sagas

2 Frankish accounts of a 9th century Viking leader named Ragnar

3 Ragnar's sons

4 Sources and historicity

5 In popular culture

6 See also

7 Footnotes

8 References

9 Further reading

The Viking Sagas

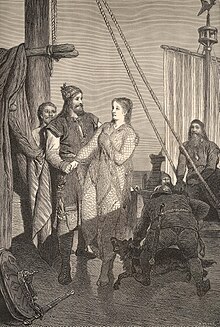

Ragnar receives Kráka (Aslaug), as imagined by August Malmström.

19th century artist's impression of Ælla of Northumbria's execution of Ragnar Lodbrok

According to the Tale of Ragnar Lodbrok, Ragnar was the son of the Swedish king Sigurd Hring.

The Hervarar saga tells that when Valdar died, his son Randver became the king of Sweden, while Harald Wartooth became the king of Denmark. Then Harald conquered all of his grandfather Ivar Vidfamne's territory. After Randver's death, his son Sigurd Hring became the king of Sweden, presumably as the subking of Harald. Sigurd Hring and Harald fought the Battle of the Brávellir (Bråvalla) on the plains of Östergötland, where Harald and many of his men died. Sigurd ruled Sweden and Denmark from about 770 until his death in about 804. He was succeeded by his son Ragnar Lodbrok. Harald Wartooth's son Eysteinn Beli ruled Sweden as Ragnar's viceroy until he was killed by the sons of Ragnar.

The Tale of Ragnar's Sons tells that the Great Heathen Army that invaded England in 865 was led by the sons of Ragnar Lodbrok, to wreak revenge against King Ælla of Northumbria who had supposedly captured and executed Ragnar.

Frankish accounts of a 9th century Viking leader named Ragnar

The Siege of Paris and the Sack of Paris of 845 was the culmination of a Viking invasion of the kingdom of the West Franks. The Viking forces were led by a Norse chieftain named "Reginherus", or Ragnar.[4] This Ragnar has often been tentatively identified with the legendary saga figure Ragnar Lodbrok, but the accuracy of this remains a disputed issue among historians.[5][6] Around 841, Ragnar had been awarded land in Turholt, Frisia, by Charles the Bald, but he eventually lost the land as well as the favour of the King.[7] Ragnar's Vikings raided Rouen on their way up the Seine in 845,[8] and in response to the invasion, determined not to let the royal Abbey of Saint-Denis (near Paris) be destroyed,[8] Charles assembled an army which he divided into two parts, one for each side of the river.[5] Ragnar attacked and defeated one of the divisions of the smaller Frankish army, took 111 of their men as prisoners and hanged them on an island on the Seine.[5] This was done to honour the Norse god Odin,[4] as well as to incite terror in the remaining Frankish forces.[5]

Ragnar's sons

The Great Heathen Army is said to have been led by the sons of Ragnar Lodbrok, to wreak revenge against King Ælla of Northumbria who had supposedly executed Ragnar in 865 by casting him into a pit full of snakes.[9] The Great Heathen Army was organized and led by the brothers Ivar the Boneless, Ubba, Halfdan, Björn Ironside, Hvitserk, and Sigurd Snake-in-the-Eye. The first four are known historical figures.[10]

Ivar the Boneless was the leader of the Great Heathen Army from 865 to 870, but he disappears from English historical accounts after 870[11]. The Anglo-Saxon chronicler Æthelweard records Ivar's death as 870[12]. Halfdan Ragnarsson became the leader of the Great Heathen Army in about 870 and he led it in an invasion of Wessex[13]. A great number of Viking warriors arrived from Scandinavia, as part of the Great Summer Army, led by King Bagsecg of Denmark, bolstering the ranks of Halfdan's army[14]. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the Danes battled the West Saxons nine times, including the Battle of Ashdown on 8 January 871, where Bagsecg was killed[15]. Halfdan accepted a truce from the future Alfred the Great, newly crowned king of Wessex[16].

Halfdan succeeded Bagsecg as King of most of Denmark (Jutland and Wendland) in about 871. Bjorn Ironside became King of Sweden and Uppsala in about 865, (the same year his father Ragnar is said to have died). Bjorn had two sons, Refil and Erik Björnsson. His son Erik became the next king of Sweden, and was succeeded in turn by Erik the son of Refil. Sigurd Snake-in-the-eye became King of Zealand and the Danish Isles in about 871, and also succeeded his brother Halfdan as King of Denmark in about 877.

Sources and historicity

The saga as published by Norstedts in a large-size illustrated version (1880).

Whereas Ivar the Boneless and Halfdan Ragnarsson are widely considered to have been actual historical figures, opinion regarding their supposed father is divided, but stories about him are mostly believed to be fictional. According to Hilda Ellis Davidson, writing in 1979:

"Certain scholars in recent years have come to accept at least part of Ragnar's story as based on historical fact."[17]

A generation later, however, Katherine Holman, writing in 2003, expressed the more nuanced contemporary opinion:

"Although his sons are

historical figures, there is no evidence that Ragnar himself ever lived, and he seems to be an amalgam of several different historical figures and pure literary invention."[18]

According to traditional sources, Ragnar (possibly as a literary composite) was:

- married three times, to the shieldmaiden Lagertha, the noblewoman Thóra Borgarhjǫrtr and Aslaug (also known as Kráka, Kraba), a Norse queen

- the father of historical Viking figures including Ivar the Boneless, Björn Ironside, Halfdan Ragnarsson, Hvitserk, Sigurd Snake-in-the-Eye and Ubba[10]

- captured by King Ælla of Northumbria and died after Ælla had him thrown into a pit of snakes

- avenged by the Great Heathen Army that invaded and occupied Northumbria and adjoining Anglo-Saxon kingdoms[10]

The most significant medieval sources that mention Ragnar include:

- Book IX of the Gesta Danorum, a 12th-century work by the Christian Danish chronicler Saxo Grammaticus

- the Tale of Ragnar's sons (Ragnarssona þáttr), a legendary saga

- the Tale of Ragnar Lodbrok, another saga, a sequel to the Völsunga saga

- the Ragnarsdrápa, a skaldic poem of which only fragments remain, attributed to the 9th-century poet Bragi Boddason

- the Krákumál, Ragnar's death-song, a 12th-century Scottish skaldic poem

The extent of Ragnar's historicity is not clear.

In her commentary on Saxo's Gesta Danorum, Davidson notes that Saxo's coverage of Ragnar's legend in book IX of the Gesta appears to be an attempt to consolidate many of the confusing and contradictory events and stories known to the chronicler into the reign of one king, Ragnar. That is why many acts ascribed to Ragnar in the Gesta can be associated, through other sources, with various figures, some of whom are more historically tenable. These candidates for the "historical Ragnar" include:

- the Reginherus or Ragnar who besieged Paris in the mid-9th century

- King Horik I (d. 854)

- King Reginfrid (d. 814), a king who ruled part of Denmark and came into conflict with Harald Klak

- possibly the Ragnall (Rognvald) of the Irish Annals[3]

So far, attempts to firmly link the legendary Ragnar with one or several of those men have failed because of the difficulty in reconciling the various accounts and their chronology. Nonetheless, the core tradition of a Viking hero named Ragnar (or similar) who wreaked havoc in mid-9th-century Europe and who fathered many famous sons is remarkably persistent, and some aspects of it are covered by relatively reliable sources, such as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.[citation needed]

In popular culture

Ragnar Lodbrok features prominently in:

History's 2013 TV series Vikings

Edwin Atherstone's novel Sea-Kings in England

Edison Marshall's 1951 novel The Viking

- "Ragnar le Viking", a 1955 comic book feature written by Jean Ollivier with art by Eduardo Teixeira Coelho, that ran in the French Vaillant magazine up to 1969

- Richard Parker's 1957 historical novel The Sword of Ganelon explores the character of Ragnar, his sons, and Viking raiding culture

- The 1958 film The Vikings based on Marshall's novel, in which Ragnar, played by Ernest Borgnine, is captured by King Ælla and cast into a pit of wolves; a son named Einar [sic], played by Kirk Douglas, vows revenge and conquers Northumbria with help from half-brother (and sworn enemy) Eric (played by Tony Curtis), who also had much to avenge upon King Aella

Harry Harrison's 1993 alternative history novel The Hammer and the Cross depict Ragnar being shipwrecked, captured and executed, as well as his sons' revenge- Various strategy video games with a historical setting, including Civilization III: Play the World, Medieval: Total War, Civilization IV: Warlords,' 'Age of Empires II: The Forgotten and Crusader Kings II

Bernard Cornwell's novel The Last Kingdom and the BBC America's series of the same name opens with the invasion of the Great Heathen Army to avenge Ragnar's death.[19]

See also

- List of legendary kings of Denmark

- List of legendary kings of Sweden

Footnotes

^ Magnusson 2008, p. 106.

^ Harrison 1993, p. 16.

^ ab Davidson 1980, p. 277.

^ ab Kohn 2006, p. 588.

^ abcd Jones 2001, p. 212.

^ Sprague 2007, p. 225.

^ Sawyer 2001, p. 40.

^ ab Duckett 1988, p. 181.

^ Karasavvas, Theodoros. "Ragnar Lothbrok: The Ferocious Viking Hero that Became a Myth". Ancient Origins. Retrieved 2018-04-28..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abc Holman 2003, p. 220.

^ Forte, Angelo; Oram, Richard; Pedersen, Frederik (2005-05-30). Viking Empires (First ed.). Cambridge University Press.

ISBN 9780521829922

^ Giles, J. A., ed. (2010-09-10). Six Old English Chronicles: Ethelwerd's Chronicle, Asser's Life Of Alfred, Geoffrey Of Monmouth's British History, Gildas, Nennius And Richard Of Cirencester. Kessinger Publishing, LLC.

ISBN 9781163125991

^ Forte, A; Oram, RD; Pedersen, F (2005). Viking Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2. p. 72

^ Hooper, Nicholas Hooper; Bennett, Matthew (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated Atlas of Warfare: the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press.

ISBN 0-521-44049-1. p.22

^ Costambeys, M (2004). "Hálfdan (d. 877)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49260

^ Forte, A; Oram, RD; Pedersen, F (2005). Viking Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2. p. 72-73

^ Davidson p. 277

^ Holman 2003 p. 220

^ "'Last Kingdom' Stars: Where Have You Seen Them Before? | BBC America". BBC America.

References

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Saxo Grammaticus (1980) [1979]. Davidson, Hilda Roderick Ellis, ed. Gesta Danorum [Saxo Grammaticus: The history of the Danes: books I–IX]. 1 & 2. Translated by Peter Fisher. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer. Chapter introduction commentaries. ISBN 978-0-85991-502-1.

Harrison, Mark (1993). "Viking Hersir 793-1066 AD". Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-318-6.

Holman, Katherine (2003). Historical dictionary of the Vikings. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-4859-7.

Magnusson, Magnus (2008). The Vikings: Voyagers of Discovery and Plunder. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-340-7.

Sögubrot af nokkrum fornkonungum. c. 1200.

Kohn, George C (2006). Dictionary of Wars. ISBN 978-1-4381-2916-7.

Further reading

McTurk, Rory (1991). Studies in Ragnars saga loðbrókar and Its Major Scandinavian Analogues. Medium Aevum Monographs. 15. Oxford. ISBN 0-907570-08-9.

- Strerath-Bolz, Ulrike (1993). Review of Rory McTurk, Studies in "Ragnars saga loðbrókar" and Its Major Scandinavian Analogues, Alvíssmál 2: 118–19.

- Forte, Angelo, Richard Oram, and Frederik Pedersen (2005). Viking Empires. Cambridge University Press,

ISBN 0-521-82992-5.

Schlauch, Margaret (transl.) (1964). The Saga of the Volsungs: the Saga of Ragnar Lodbrok Together with the Lay of Kraka. New York: American Scandinavian Foundation.

Sprague, Martina (2007). Norse Warfare: the Unconventional Battle Strategies of the Ancient Vikings. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-7818-1176-7.

Waggoner, Ben (2009). The Sagas of Ragnar Lodbrok. The Troth. ISBN 978-0-578-02138-6.

| Legendary titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sigurd Ring | King of Sweden in West Norse tradition | Succeeded by Eysteinn Beli |

| Preceded by Harald Greyhide | King of Denmark | Succeeded by Sigurd Snake-in-the-Eye |

| Preceded by Siwardus Ring | King of Denmark in Gesta Danorum | Succeeded by Siwardus III |